Brigitte Lang is a jewelry maker based in Perchtoldsdorf, Austria. The work series Defence Reactions, from 1981–1985, has become widely recognized due to its presence within the Sammlung Verbund collection of feminist avant-garde art in Vienna, in which Lang is the only jewelry maker represented amongst the artists.[1] It’s an honor to talk with her more about feminism and jewelry, and the emancipation of jewelry in the art scene.

Katharina Kielmann: How does it feel to represent feminist jewelry in an art collection?

Brigitte Lang: It has been one of my greatest honors to be recognized in this collection. Gabriele Schor, the director of the Sammlung Verbund, was searching for Austrian artists from the 70s and my work was recommended to her. (And I’m happy to experience that as a still-living artist!) Right now I am the first jewelry maker in the collection. I feel very proud to represent this field in the art scene.

As Schor says, there was a sheer existential need for female artists of the 70s to express themselves in a feminist way[2] during the second wave of feminism. Could you explain how you developed the Defence Reaction series in 1981?

Brigitte Lang: Back then it was in the air, many female artists were working on feminist topics. For me, it was also very private. In the manner of the quote that the “private is political,”[3] I needed to react publicly about my experience with my former relationship partner.

In this relationship there was fighting, a duality of genders and disciplines. My partner was also an artist, a painter. He harshly criticized my work, saying that I should do something more pleasing with jewelry. However, I always had a clear mind regarding what I wanted to express, which drove him crazy. He even damaged art pieces of mine. So I started to reinforce my inner resistance with the idea of defense jewelry for me on my body. Therefore all the jewelry pieces were made to fit my measurements, just for me to wear.

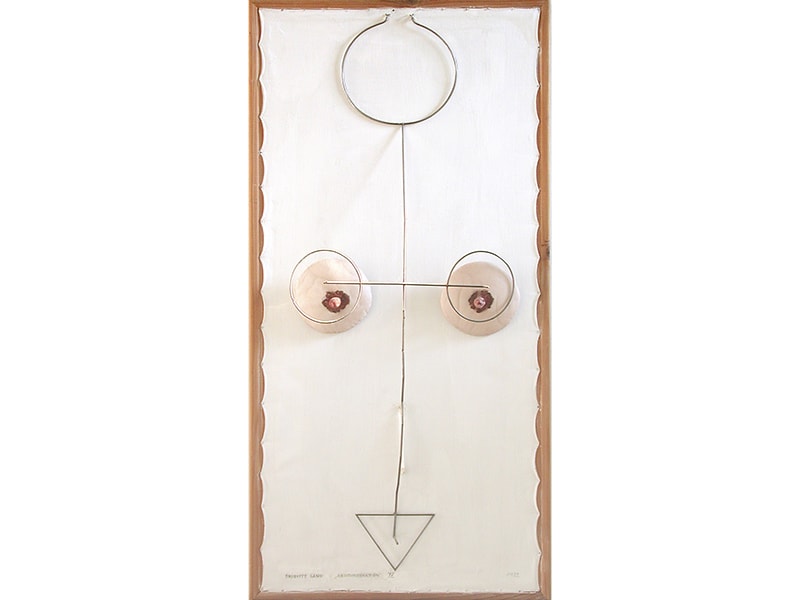

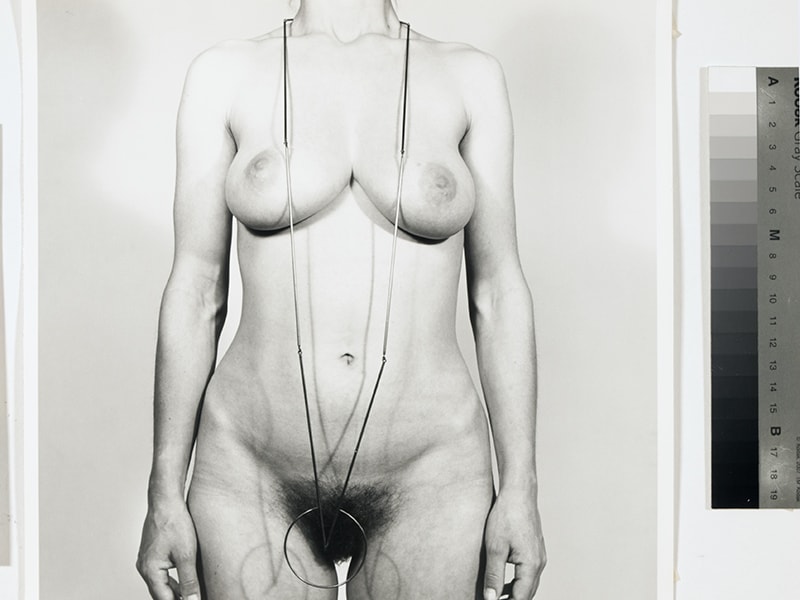

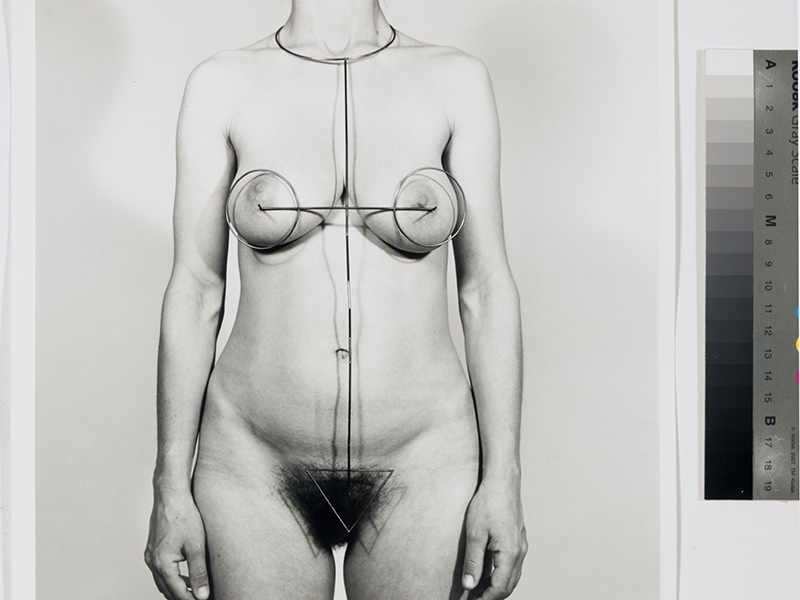

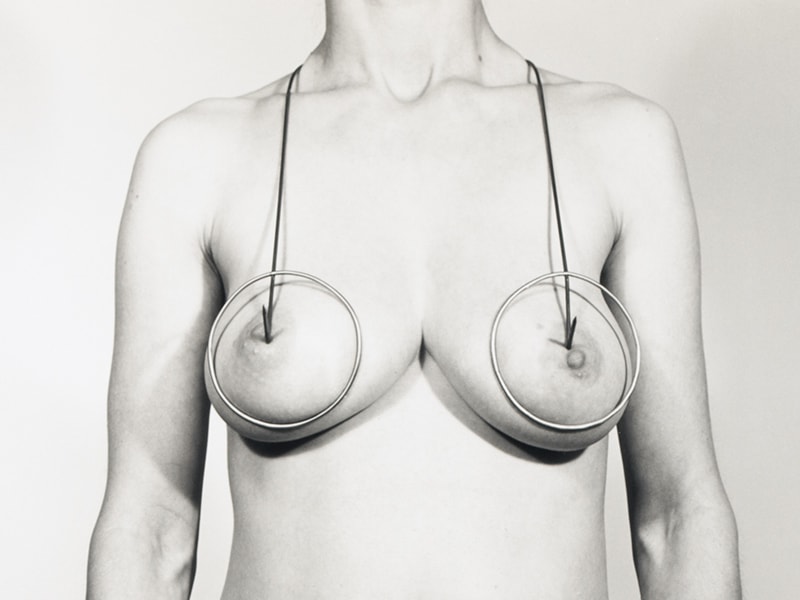

I started crafting the first three jewelry works to wear around the neck over the front of the body out of steel and brass. They were abstract linear drawings over different body parts: one over the breast, one over the vulva, and one over the breast and vulva together. At first, these objects seem harmless, just amplifying gestures. But if you were to examine more closely you would see that the wire sticks out in certain spots, like a stinger. The parts beneath the stingers, like the vulva and the nipples, are then not defenseless anymore. With this stinger, they evolve into an aggressive weapon.

I used many characteristics of the first series for the second series as well. Here I was searching for a stronger narrative to cope with the inner pain of society. This trio was my defense at the time: against the structural approach of being seen as a wife (though I wasn’t married), of being hurt, of being touched. And we see stingers on them: a “wedding veil” with stingers in front of the eyes; the red lips have a big red thorn set in the middle; and the crown, with a piece of a thorny branch mounted on it.

Some of my artistic colleagues were shocked when they saw the thorny crown—it was blasphemy to show oneself as a woman wearing what they saw as a religious symbol. But I never aimed to provoke in this direction, as I am a person of faith myself. I just viewed this crown as a symbol for the state of suffering. And this, to me, is gender free—it’s human to defend oneself, and, if one isn’t heard, to shout it out, like I did.

All three objects have a piece of cloth under the neck. Was it to postulate nursing the wounds of people who are hurting?

Brigitte Lang: It was meant as an empathic gesture toward me. What you see in the work is in some sense my pain and my blood. The cloth at the neck represents a kind handling of myself. The object did not serve to go into battle with an opponent, but to have a defense in case sombody tried to hurt me. Although the object looks actively aggressive, it was meant as the opposite—to discourage.

The white jacket I wore in the photographs references the time I spent working at a psychiatric hospital in Vienna, from 1975–1978. I was interested in that field because early on I experienced the drawings of an intellectually disabled person. That touched me deeply. It was work on the razor’s edge, with the aim to get to the bottom of the soul. In me is also the ability to be a very strong nurse toward people. In combination with my experience at the psychiatric hospital, it forced me more to activate a comunication field for topics like feminism that made some [or many] people uncomfortable.

You were working with two more strategies to display the work: photography and canvases. Tell us more about those desicions.

Brigitte Lang: If I had not made the photographs of me with the jewelry, I’m not sure whether the jewelry would exist now anymore, or if it would be possible to communicate the history of that time so well. Those photos show me wearing the jewelry. Thinking back to that time now, I feel I should also have gone out on the streets with it, like Valie Export did with her art pieces.

For my first series I also chose to drape them on canvas, with breast and vulva shapes made out of nylon stockings and horsehair as stand-ins for the body parts over which the pieces are supposed to be worn. I would not choose a vitrine, because it wouldn’t be understandable. This jewelry needs a wearer, like the canvas is the wearer of a story.

Did you always have a distinct connection to your body as a performative platform?

Brigitte Lang: Unconciously, yes, but I only realized that later, for example when I saw Lady Gaga with the meat dress on. This was something I had already done in 1973, when I had to find a dress for Carnival, and decided to go as meat. I was wearing this cloth with real schnitzel applied to the front. In my jewelry I also inserted this feeling for performance, in casting body parts or making a bracelet that had rings in the form of little human bodies for each link. So I tended to work with and on the body pretty playfully. On the other hand, I’m also interested in the combination of “human body” and “room.” This was the strongest push formally to become bigger and bigger, to describe with the body bigger rooms, bigger cages, in which the human acts and reacts. For all intents and purposes I see the body as an unlimited field of possibilities.

Going back in time, the period that most shaped your education began in 1973, at age 15, when you attended Ortweinschule,[4] a school for applied art in Graz, Austria, where you joined the metal class. Could you explain the most important lessons for your thinking as a jewelry maker?

Brigitte Lang: For me, everything artistically happened for the first time at this school. I came from a very simple family in a little village 50 km from Graz. I had no paragons. I probably chose jewelry because it was something I could imagine. When I attended on the first day with two braided buns, I stared at the men, who were allowed to wear their hair long—it was a relaxed, hippie atmosphere. The teachers, who had mostly graduated from the Akademie in Vienna, focused on the quality of the craftsmanship. The classes were mixed so we could sit between beginners and master students at the same time. For jewelry, there were no borders artistically. As one of my former teachers, Richard Kriesche, said: Even sweat on the skin is jewelry. Up to this day, this has shaped my view of myself as a craftsperson who makes jewelry, paintings, and objects with an open perspective.

After you finished school in Graz, you applied for the painting class at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, in Vienna, although you weren’t accepted. At this time you thought that painting was the highest craftsmanship. How did your approach change to one of emancipatory philosophy for your discipline?

Brigitte Lang: I chose painting because I wanted to make more art. But later I realized that I was already making art, only the medium was different: The body is my canvas, the metal is the paint, and my blacksmithing workshop is my paintbrush. And the body (such a good canvas) is a better site for display than a wall.

Even today there is an issue for jewelry makers, when entering the art market, concerning naming what they make “jewelry.” How did you experience this discrepancy in the art world?

Brigitte Lang: I consider all my works jewelry when it’s possible to wear them on the body. Therefore I sometimes felt resentful if people were judging when I said that it is jewelry first and foremost. Also, I make paintings and objects and never feel this discrepancy toward the different fields or feel ashamed that I make jewelry. It might be possible that a jewelry piece of mine is considered as an object at first. But the precise meaning of the work only reveals itself fully when the piece is worn.

In 1982 with your jewelry art you were fighting for equality with the idea of creating more respect and tolerance between genders. What is your aim today, when you’re working within the feminist field?

Brigitte Lang: To me the women’s perspective was feminist. This was of course just one perspective, and I was never interested in classifying and comparing the genders. So today I aim for the commonality of all humans and I would express myself differently on the body, not in that classical frontal way, but by playfully seeking more possibilities on new places on the body as a display and canvas for my jewelry.

Thank you, Brigitte Lang, for this interview.

[1] See more about the Verbund collection here: https://www.verbund.com/en-at/about-verbund/responsibility/art-collection.

[2] Gabriele Schor, ed., Feministische Avantgarde. Kunst der 1970er-Jahre. Werke aus der Sammlung Verbund, Wien (Munich: Prestel, 2016), 13.

[3] Angela Harutyunyan, Kathrin Hörschelmann, and Malcolm Miles, eds., Public Spheres after Socialism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 50–51.

[4] The school still has an educational program for jewelry makers today: https://www.ortweinschule.at/de/kunst-und-design/ms-schmuck.