HEIMATMUSEUM

Benedikt Fischer: When did you start the Heimatmuseum? When was it opened?

Suska Mackert: I have to think.

Collecting things for the current Heimatmuseum started a while ago, when I was a child. But I started this format—of a cabinet of objects, for me and my guests—in Amsterdam. That was the moment when I gave the cupboard its name. It started simultaneously with the cutting out and collecting of images from newspapers, sometime during my studies. My archive books start around the same time, in 1997/1998.

So the two-dimensional and three-dimensional collections grew simultaneously?

Suska Mackert: Yes, actually they did. Like I do with newspaper cut-out images, I started putting objects in reference with each other within the Heimatmuseum. And maybe that was the moment when I decided I would use a cabinet to arrange certain things in one compartment. Others that don’t fit the criteria of a particular compartment would have to go into another one. The things are talking with each other, so to speak, they build up relationships with one another and of course also beyond their own shelf. Border crossing. I liked the thought that things could stand in reference with each other, they could have a dialogue and as a result of that you’d feel at home—feel Heimat.[1]

There is a similarity between the Heimatmuseum and the collecting and cutting out of the newspaper images: I am not in total control, it is not one hundred percent within my power—these are things that I encounter, that are offered to me, that I come in contact with. Mainly, the objects in the Heimatmuseum are presents that I get. Sometimes they are reactions to/reflections on what I am doing, from my friends.

…and it is in a constant state of change, to a certain degree?

Suska Mackert: Yes, change is also part of it. Every now and then, the order and the combination of pieces has to be redone, the objects have to be newly grouped, especially when new things are added—additions either fit into an existing group or category automatically, or another piece has to leave for the sake of the overall order.

In a way the “order” changes every day, at least in my head. There are different chapters (categories?) that have to do with each other. But those are not rigid: The relationships as well as the chapters can evolve. This actually also has to do with the desire to understand the world, as well as the impossibility to do so. You are looking for a certain order or criteria for sorting, in order to understand better. Some aspects seem to become clearer, others won’t—in the end you fail again.

If one wants to sort or arrange something, one never fully succeeds in finding criteria or categories for everything, to find a definite classification. That is what makes this so fantastic and beautiful. There is no ultimate order, explanation, or assessment.

ATLAS

I see some connections to your latest work, Eine Ordnung des Glanzes (An Arrangement of Shine), in which an atlas plays a part. Is it your ambition to make an overview of the subject of jewelry? Contrary to common (geographical) atlases, your Atlas is constantly expanding, growing, it repeats itself and digresses. What is its relationship to reality?

Suska Mackert: Initially, when I started this project, I was driven by a scientific approach; I thought I would do an encyclopedia, a jewelry encyclopedia. Everything would be divided into certain terminologies, and in doing so, it would always proclaim its correctness, indeed a scientific correctness. However, this ultimately was not interesting for me as an artist—I am not a scientist. That absolutely does not imply that my project and its criteria are generated at random. Everything has to be very precise; it simply wasn’t laid out as a scientific work.

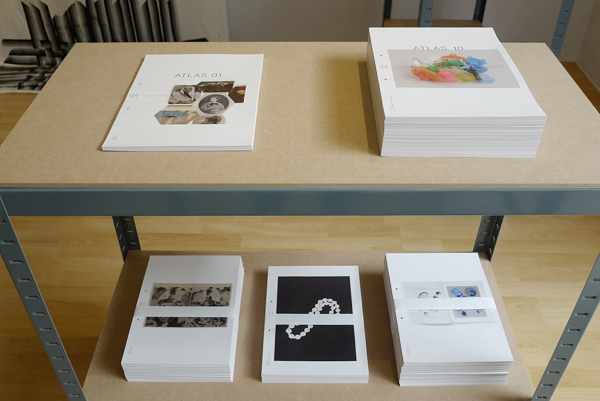

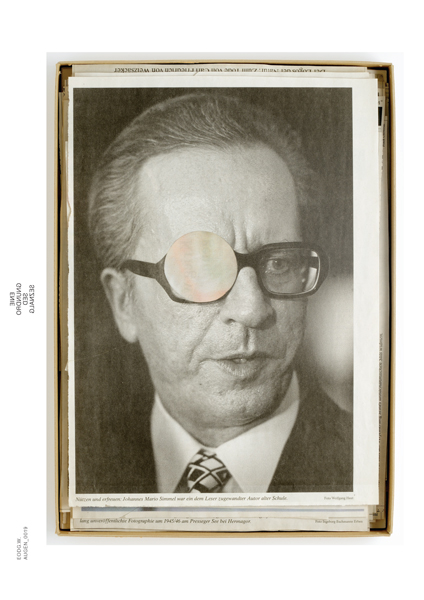

The Atlas in its ongoing indexed form is an edition, a part of the project Eine Ordnung des Glanzes (EODG). Each Atlas consists of a series of loose sheets selected from a bigger stock of images (there are 80 Atlases, all of them different). I call this stock my “archive,” and several edition projects came out of this archive. There are seven editions so far: Atlas; Augen; Geflecht; Front & Back; The Andy Warhol Collection; and Diamant and Ikonen. The numbered Atlas, like every other edition in EODG, is always an extract from my overall archive.

These different Atlases are ways to weave sub-stories out of the whole archive material: For example, I have put together specific Atlases around categories or terms like “presentation,” “representation,” “original,” “copy,” “authorship,” and “identity.” These topics are ultimately only important while the Atlas is made, as a selection criterion; the viewer does not have to see or understand the story with clarity.

A cartographic atlas has to follow strict codes, rules, and terms that are readable by society in an obvious way. But I do not use a clear, understandable coding in my project. I like to insinuate that these thoughts follow a certain “truth” and, at the same time, suggest the dubious and doubtful character of this predefined “truth”—if all this indeed functions that way. Everybody has his/her own perceptions and truths.

Absolute ideas or explicit meanings do not interest me. However, whenever an edition or an original work is created, it is in the only resolution possible at that moment: Otherwise, it would not be true or real.

In a previous interview you said that you had the desire to make a book. But your chosen form, the atlas, is not a book in a traditional sense.

Suska Mackert: This openness is very important to me. That is also the reason why I did not make a book or catalog, anything that seems closed or with a beginning and an end. Like this, the archive can grow every day. For example, I was potentially able to integrate the exhibitions at Gallery Spektrum or Rob Koudijs as part of the project. The presentation format, or how certain works were presented, how I placed them in the gallery spaces—all of this became documented in photographs that will then go into the archive. If it were a book or catalog, it would have a certain rigidity, it would take away from what I actually want to show concerning jewelry as well as everything that is connected to it. That’s why I had this basic idea of making cross connections and creating space, available space—that was important.

EDITIONS

Next to the editions you also show “original works.” Tell me about that.

Suska Mackert: Archive, editions, and originals stand in contrast to one another, but are connected. Usually the original works are very fragile, almost skeletal; and the editions are mostly rather solid. They are very different from each other. Different questions arise out of their juxtaposition, and other possibilities.

The difference manifested itself through the gallery presentation on shelves. Spectators could go back and forth, look at the things, form connections. The shelvings had different levels and this enabled me to work with another dimension, although the space was rather small.

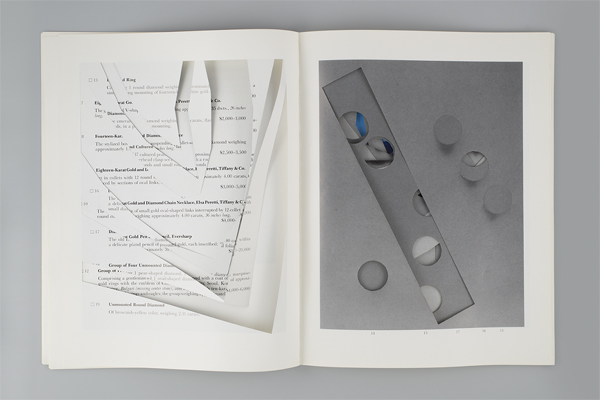

For example, the “original” Andy Warhol Collection, where I literally cut out all the jewels from the auction catalog, is of course a very different work from The Andy Warhol Collection “edition.” That work is dealing with the infrastructure of a catalog, the world of Andy Warhol, with his collection, the fetishism behind it, different layers that you can literally feel through the fragility caused by the removal of the jewels.

REALITY

Suska Mackert: There are other, additional layers in the “edition” version of the Andy Warhol Collection. It consists in the complete black and white reproduction of the original. The pages of the edition are not literally cut out, like the original is. The black and white reproductions of the original spreads are interspersed with single-page color reproductions.

Which of the two versions is the more real? Does black and white mean more reality, because you can see whatever color you want to read/see? Does color imply more proximity to reality because it seemingly depicts what we all see? Because it shows reality how it really is?

The first time you used that method was for the work Somewhere Else, right? Where you can see landscapes with mines in color, and the cut gemstones that are harvested there in black and white.

Suska Mackert: Yes, but I would say even earlier—for my final exam at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. Back then I made jewelry in black and white. I showed it on a table, gray jewelry that was deprived of all the qualities a piece of jewelry usually has, any kind of identity that would describe a jewel. The gloss, the gold or the material, the stones, the color—everything was taken away. You could therefore say it was “reduced,” as it was black and white, but maybe much more real, only represented through its shape. And despite this, or because of that, it was readable for everyone as a piece of jewelry.

The work Somewhere Else is based on the thought that, normally, the stones that are found (or shown) in the mines are viewed in beautiful colors and of course also in convincing colors. That is how this whole gemstone mining is being romanticized. One shows color images of beautiful landscapes and colorful images of gemstones. At the same time, though, it is very well known that the mining of stones is not as romantic in reality. That is why it couldn’t just be a pretty postcard with mountains and stones next to it, I wanted to show this “truth” by taking the color of the stones away.

RELIGION AND EXILE

Since we are on the subject of “truth” now, would you mind if we talked about religion at this point?

Suska Mackert: What are you interested in?

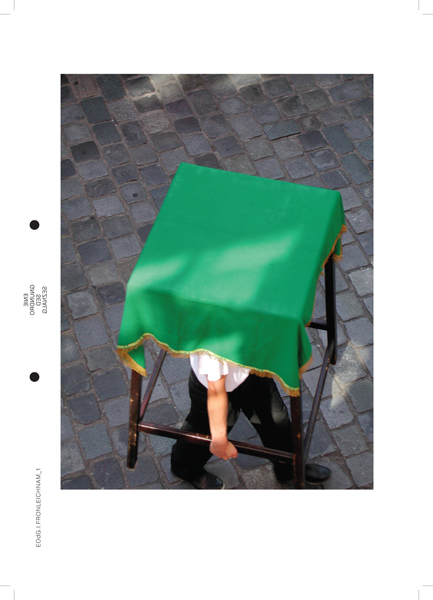

When I got the invitation to your show at Gallery Spektrum, it showed an image referenced as Fronleichnam (Corpus Christi), featuring a man carrying a table on his head. I did not recognize what it was, despite my slightly Catholic upbringing.

Suska Mackert: They carry that thing/a table that is supposed to present the monstrance or Madonna. In this particular case what is carried around is a table with a green tablecloth on top of it. When the procession comes to a standstill, they put the Madonna on top of it. When the procession carries on, the men hold the Madonna in their hands. It would be too unsteady otherwise.

Suska Mackert: They carry that thing/a table that is supposed to present the monstrance or Madonna. In this particular case what is carried around is a table with a green tablecloth on top of it. When the procession comes to a standstill, they put the Madonna on top of it. When the procession carries on, the men hold the Madonna in their hands. It would be too unsteady otherwise.

You found it interesting because it shows absence?

Suska Mackert: Yes, because it shows absence twice. The missing object on the table, but at the same time the person that carries the table—hidden under the tablecloth. It becomes a headpiece or a protection—everyone can have different associations. In any case, the identity of this person is hidden. The protecting fabric becomes also something surreal. This person with the table on his head passes by you in a procession—his head camouflaged with a cloth: That is jewelry. The table transforms into a piece of jewelry: into something you wear as protection or because it makes one more beautiful, hides or enhances their identity—all the things that jewelry can also do.

As you know, I also grew up in a Catholic village and once you arrive here (in Nuremberg) from Amsterdam, you cannot help but notice how often the church bells ring and how many pointy bell towers there are.

Suska Mackert: Indeed. I also had a different reaction toward religion or belief when I was living in Amsterdam than I have now, here in the Bavarian part of Germany. Leaving Germany gave me the possibility to see the things that shaped me early on: how I am as a “German” woman, my way of thinking, and so forth. As a result, I grew much more aware of these things and they became much more important to me. Realizing what was missing—what I missed, but had been unaware I was missing—gave me the option to get to know myself much better. Again this shows you the role absence can play. I had to position myself in a foreign country to see how I am and what I carry inside of me, because my familiar context was gone. I had to find out—at the Rietveld—what I do or what I want as an artist. What interests me and what doesn’t. Before that these question did not exist, in that sense.

Sounds familiar. It’s easier to identify those things with a greater distance.

Suska Mackert: Yes. If I would have stayed in Germany I might never have ordered the Frankfurter Allegemeine Zeitung—a German newspaper from which I cut out most of the images I collect. Or I might never have read these articles or been able to newly appreciate the German language. I don’t know. It is the same with belief or religion. I developed a certain longing for something that could be connected with religion or spirituality, maybe. Because this is not so present in everyday life in the Netherlands, or at least I did not see it.

I doubt I would have been able to develop this desire in Nuremberg because the Church is so present that all you want to do is reduce its presence: You don’t want to be confronted with it. There is a lack of space to discover it on your own; the institution is too strong. If I go into the Dome of Bamberg, it has a very different aura than if I go to church here, in Nuremberg. There, I foremost feel a concentration that has nothing to do with the institution, but has to do with spirituality, with belief. Bamberg gave me the means to undock these definitions from each other.

This went hand in hand with devotion, attention, quiet moments. Now that we talk about it, this is also something strongly connected with the muse—traditionally seen as a female feature.

Often it is assumed that faith or religion, the institution of the church, are male concerns. But that is not the case for me, I don’t see it as “male.” It is not a male patriarchy for me. Faith has nothing to do with that. I still remember when I was in church as a kid, especially the ritual preceding the service: The sequence of the liturgy was a grounding point. The repetitions, the frankincense, the sensual perceptions—all these things you hardly come across in everyday life (or if it did, then it happened at home, for example when my mother would bake a cake.)

Of course I could not follow all that was being said, the homily or the texts, and so I concentrated on other things. Your gaze would wander and you had your own thoughts about it and moments of concentration or calm, where you do not talk, where things can happen inside your head or perception.

I think for a country child like me, church was the closest thing to an exhibition you could get. Art, or something like art, just did not exist in the countryside. All these golden, squiggly forms…

Suska Mackert: Yes, and that you can feel the craft and love with which these things are made. There is a very dignified handling of these objects.

DIALOGUE

Speaking about handling: what are your expectations toward the viewer? Do you have any?

Suska Mackert: I can’t—what should I expect? I cannot say that I expect something; I am glad if someone sees something or has certain experiences when he/she looks at the work or if they have a chain of thoughts. Maybe synapses spark or sizzle all of a sudden. Exhibitions function like an engine: They invite specific conversations about my work, or questions, or misunderstandings that inspire me to go on with my work. I am excited about talking to the people that visit it—when I can be there in person—or if they call or write me about it. That gives me the chance to learn or discuss it in another light—to understand that the focus lies somewhere else. So if you ask about my expectations then it is to be able to have a dialogue. That is then the actual work for me. However it takes place.

Are you ever bored?

Suska Mackert: No.

I was afraid you would say that.

Suska Mackert: No, but I would like that, to be bored. There are so many things I would want to do if I got bored. For whatever reason, I would like to embroider an image on a really big scale, already have for a long time.

For that you need quiet.

Suska Mackert: Yes. I would also like to hold a discourse or salon with friends or colleagues. Where you cook together, talk, maybe look at things together—whether a movie or an exhibition—live life together. That was much more the case in Amsterdam than it is here.

Sometimes I hear that I make no separation between life and work, but if you ask me, it could merge even more. Become one. I like how my son Esan, for example, participates when we have guests or when we cook together or meet with the students. I always carry with me the thought of a house for several generations—something like Black Mountain College. It always returns to me. Where you work together and you live together and the center of focus is art and culture.

I am convinced that such environments would have a totally different swiftness—not in the sense of tempo or efficency, but that it would have another dynamic—some kind of naturalness—that is not possible to achieve alone. Maybe it has to do with being part of something bigger.

COLLABORATIONS

Suska Mackert: Back then, when Manon van Kouswijk and I were asked if we would like to make an exhibtion together, it was strange for us at first, because we thought that our works were so different: Why would we do something together? But the exciting thing was foremost the exchange between the two of us, to work and experience this time together.

Where did you show?

Suska Mackert: At Huis Rechts, which was an artist initiative by Celio Braga.

That was the video ze stond dicht bij mij (she was standing close to me) that you did together?

Suska Mackert: It was actually a whole exhibition; we created the whole room and its atmosphere there. Each one of us incorporated an existing work. We visited each other in our respective ateliers and chose things there, which we then continued to work on in the exhibition space.

We then created elements in the room that put our works in a dialogue, with regards to form and content.

The beautiful thing about working together is that you share many things and talk about things, you can criticize one another’s working process and discuss. At the same time you also share the responsibility. I feel that exhibiting is a big responsibility: Often one makes things alone and is completely responsible for it.

For the project EODG I really enjoyed working with the graphic designer Christine Alberts. Through this collaboration, everything fell into place, in a very different way than it would have done had I been alone.

Generally, how does it feel for you to show in a jewelry gallery?

Suska Mackert: All in all, I think it makes sense and it is exciting. The jewelry gallery—the jewelry context—is a place where one deals with jewelry, in whichever way that might be. It is not a necessity for the understanding, the internalizing, or the viewing of my work, but I consider that it makes sense. And it is important that a gallery actually show different positions, different approaches. Also in order to do the work justice, a gallery should not be a shop or store. First and foremost it should be exactly that, a gallery. But one for contemporary jewelry.

What exactly this entails is to be decided by the artist showing there.

Do you think that jewelry with all its potential is utilized?

Suska Mackert: No, unfortunately not. And this is true for vessels as well.

Jewelry is such a rich medium—inexhaustible. At first glance it seems as if the amount of people engaged with it has increased in the last few years. Nowadays, there are more places to study jewelry, more workshops and so on. Through the use of the Internet one has much more, and easier, access to it all. But at the same time, this is a false conclusion.

With this diversification, a lot of depth gets lost. A big amount of honest and true examination of the field seems to dwindle. Almost as if one can take this and that element from what is on the Internet, and voilà!, one has become a jewelry artist.

What counts is to experience and examine things on one’s own.

Discourse. Time.

This reminds me of what Dorothea Prühl expressed with some jewelry “being eaten before it even cooked.”

Suska Mackert: Yes—and if that happens constantly, you really get stomach aches! And one never reaches the full joy, the full pleasure—the capacity, the potential, that such a meal can offer. It is not fully taken advantage of. This comes from a delusional drive—wanting to be more effective, sufficient, and achieve more general things—more mass.

That does not mean that the motor should be taken out—on the contrary, it is not about speed. But about a true, real examination.

If students take a trip to the library and dedicate a week to really digging deep into jewelry books, like for example by Bernhard Schobinger or Daniel Kruger (I am citing those because those were just recently published), I believe that they will gain a different perspective and insight into jewelry, as compared to looking at everything jewelry-related on Facebook for a week: Facebook does not have anything to do with a real examination of the medium, and does not lend itself to internalizing and processing of what is happening.

For oneself.

Suska Mackert: Yes, I think it is fatal, because it seems like the Internet is speeding up this process. It allegedly makes the understanding of what the field is about much easier.

You are not represented much online!

Suska Mackert: No. My work does not translate well on the Internet, this way of consuming content in a very limited amount of time. I think that is fine.

IMMATERIALITY

Cutting out, painting over, making a show about work that is not actually present at the show, pixelating… Do you ever have the desire to make art without actual tangible work?

Suska Mackert: That is what I am interested in. “As little as possible” is a topic I am dealing with for sure. It has to do with the fact that jewelry can be very little—but move a lot, change a lot. For a person, or the identity, or the charisma, or the meaning. And this is the main, most captivating aspect of jewelry for me.

There are also works that only exist in the moment as a materialized thought, for example the pins (Eine Ordnung des Glanzes—Alles oder nichts). The ones that are lying next to each other or are glued together, they only exist within the atlas, as an image. I don’t see any point in those pieces existing as wearable jewelry. One could ask, “why don’t you turn that into a piece that is wearable?” but that is not what I am looking for at this moment, to have a finished piece of jewelry; rather I am interested in the thought or the suggestion, the possibility, that it exists.

And do you think there are topics within jewelry that you didn’t work with, but are tempted to follow up on?

Suska Mackert: There still are some, I think. I recently saw the exhibition Disobedient Objects in London, which was very interesting for me to see. If one is part of a revolution or demonstration, if one wants to change something, which attributes or objects will one make? How would you make yourself, or the topic of a demonstration, visible/notable? What attributes are important in order to do so? Which objects are used for that purpose? The answer doesn’t have to be jewelry. That is interesting to me as a topic, possibly as a project with my students.

What would you campaign for? And which media would you use to present, or represent this? This concerns uniforms. That is what interests me in the work of Vivienne Westwood: her activism and the things she does in this regard. I want to read more about that—fashion, sociology, or politics and semiotics.

Suska, if you could interview someone, who would that be?

Suska Mackert: If I could interview someone, then I would like it to be Manfred Nisslmüller.

Maybe that makes for a nice ending?

[1] The word Heimat, which is quite unique to the German language, expresses belonging in relationship to both the domestic and to the collective, and has generally positive connotations. It can be translated as “home” and “motherland.”