Olivia Shih: How did you find your way to jewelry?

Karin Seufert: As a young girl, I was fascinated by jewelry, something I could adorn myself with, something that would make me beautiful and attract attention. I quickly started making my own jewelry.

I began my education as a goldsmith and silversmith, but I soon discovered that metal techniques were not sufficient for what I wanted to create. I continued studying at Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam.

I’m still fascinated by the possibility of bringing my ideas to fruition through touchable objects. The aspect of wearing, communicating, attracting attention, working independently, the working process itself, the human body, and how the body interacts with jewelry made jewelry attractive to me.

You’ve taught in Sweden, South Africa, and Brazil, and you’ve exhibited everywhere, from New York to Tokyo. Does your experience abroad inform your work?

Karin Seufert: Definitely! You get so inspired by looking around, especially when traveling to a foreign country and observing the different ways of living, dressing, acting, being—all of these differences inform my work. Whether it is in Sweden or in South Africa, students display their background and roots in their work, their knowledge, and their way of thinking.

Why did you begin working with plastic bottle caps? Does your interest stem from environmental concerns or from the material characteristics of plastic, which has pervaded all aspects of life?

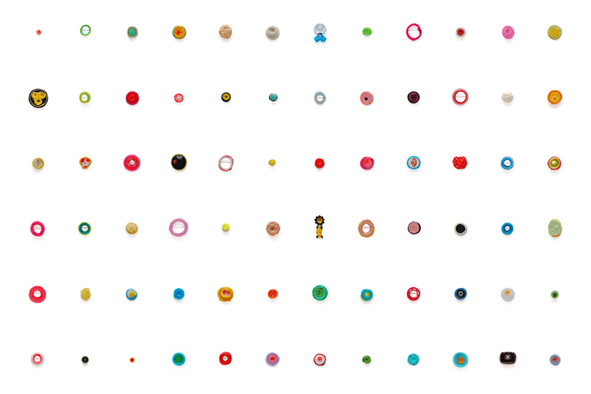

Karin Seufert: In Brazil, I found a little object made from plastic caps that caught my interest. I started to look closer, and my fascination grew. Each cap is a perfect circle in bright strong colors; some are patterned or printed, and others have unique structures. Beautiful garbage, and easily transformed into jewelry.

It was the roundness that reminded me of my PVC dots and connected with my previous work. My idea was to rebuild the Puma—the original PVC Puma functioned as the religious symbol of our time, a kind of a modern fetish—by using the plastic caps. It would become a huge piece, more object than jewelry, colorful and powerful. It would hang like a trophy, caught in a big ring but built from a typical product of our times: the endless colorful garbage of plastic caps.

From 2009 to 2010, you constructed jewelry out of cut PVC circles in a commentary about brand names and logos. How is working with PVC similar to or different from working with plastic bottle caps?

Karin Seufert: Completely different. First, I have to punch out each dot from the PVC foil. The process is concentration-heavy, sometimes even a bit meditative. I work quite small in size, and it feels more like working with textile when I stitch and embroider the PVC. You have to know from the beginning what you want, even when the resulting look brings surprises. I made my first PVC piece in 2004, and I’m still attracted by the possibilities this material offers.

Working with plastic caps is more spontaneous, sometimes completely surprising. It’s often a quick process, and I have bigger elements to handle. Depending on if I use the iron or a hot-air-gun as a way of working, the result can be very distinct. Another aspect that distinguishes plastic caps from PVC is color. With the caps there is additional fun in playing with colors.

Please describe what a day in the studio is like for you.

Karin Seufert: No day is like any other. Coffee in the morning is important! Because my studio is at home, I start by putting on my working-shoes and my working-apron to get into my working-mode.

I might start with embroidering PVC dots or ironing sliced caps, filing the core for the PVC jewelry, or working on metal mechanisms for jewelry. Photographing my jewelry is an important part of the presentation of my work. When the sun shines, and there’s good light, I start taking photos of my work.

But whatever I start with, the first hours ’til noon are the most productive ones. I manage the most within this time frame, and they are very dense hours of concentration. In the afternoon it is the same work, but the hours go quickly. Usually in the evenings I punch out PVC dots, time runs past, and the day is over before you can think about it.

Jun Konishi creates jewelry with colorful plastic curlicues carved from plastic bottles, and Susie Ganch has made oversized jewelry out of plastic debris—why do you think artists are drawn to the combination of jewelry and such an inexpensive, mundane material?

Karin Seufert: It is the pleasure of discovering and developing something new from something old, of transforming something cheap and worthless into something precious. These are the reasons why jewelers like to work with this material. Another reason is the diversity of the plastic products and the garbage of today, which continuously increases. Plastic can be attractive—the bright strong colors, the shiny surface, the ease of handling and creating something unexpected. Plastic is only one of the many cheap materials, but there are others, like wood, paper, steel, etc.

Your work is often photographed on people with their individual quirks and characteristics; is it important to you that each piece of jewelry interact with a different individual?

Karin Seufert: It is important to me to photograph my jewelry on people because my pieces are related to people and interaction. A photograph of the jewelry worn by a person tells more about the piece than words can, since you immediately see the relationship between the wearer and the jewelry.

Before I take a photo I think about whom this piece could fit the best and why. Not every piece suits everyone. When we start with the photo session, I avoid giving instructions and leave it to the person to decide what he or she wants to wear and where to place the jewelry on the body. While I make my jewelry, I don’t have someone specific in mind, but it is sometimes surprising to see how the piece and the wearer fit together or don’t.

The show at Pont & Plas includes you, Kim Buck, and Tore Svensson, and although I would have liked to interview all of you, there is only room each month for one. I look forward to interviewing them another time. But could you describe how the three of you have started exhibiting together as KGB?

Karin Seufert: It was Kim who asked Tore and me if we would like to exhibit together during the opening of the Coolest Corner exhibition in Copenhagen. Kim has a gallery in the center of the city, and it was a great chance to show our work together in his place, especially during a time when a lot of jewelry devotees or collectors were in town.

The time was too short to develop something new, so we decided to show the newest work at that moment (June 2013).

It is fantastic to work together—Kim and Tore are professionals, and it is a pleasure to have such good colleagues by my side! The exhibition setup went easily and smoothly. Our work complemented each other’s, even though each person’s style was distinct. That was a good starting point for the continuation of this collaboration.

Our name KGB is a composition of the first letters of our hometowns (Köpenhamn, Göteborg, and Berlin) and because it evokes Russian “associations,” we serve vodka at our openings!

Have you heard, seen, or read anything of interest lately?

Karin Seufert: The Salt of the Earth, a documentary from Wim Wenders about the Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado who created different projects about the traces human beings leave on earth and about the earth itself. It is a beautiful movie, touching and surprising.

The Light Shines Only There, a Japanese movie (the story is from Yasushi Sato) about relation, family ties, desperation, and hope. It is a dark and heavy story, and many times you think what’s taking place is the worst that can happen, but you discover things can always get worse. It is a strong movie with fantastic actors.

The exhibition of Miyako Ishiuchi, the Hasselblad winner of 2014, at the Hasselblad Center in Gothenburg. I especially was touched by her series of clothing from people who were killed by the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. These photos seemed to be from another world, light and without materiality, even when it feels like you can nearly touch the clothing in the photos.