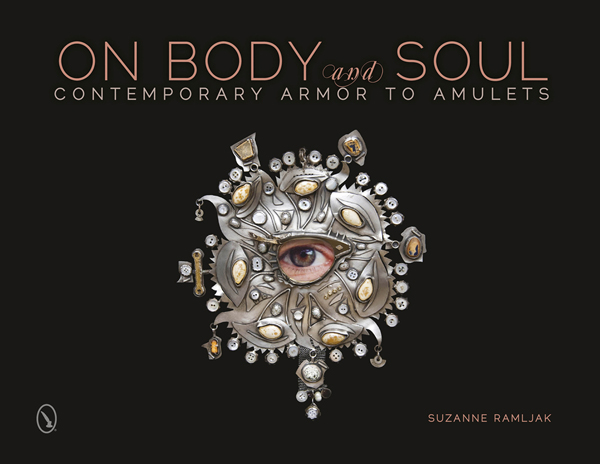

Susan Cummins: Please tell the story of how this exhibition and the related publication, On Body and Soul: Contemporary Armor to Amulets, came into being.

Suzanne Ramljak: In studying jewelry’s functions over the years, I have come to view its protective role as perhaps its most compelling. This ancient and universal dimension of jewelry addresses our essential vulnerability and attempts to overcome fear and uncertainty through wearable ornament. The ability of adornment to empower and safeguard wearers also stands in opposition to common notions of jewelry as merely decorative; jewelry in this context becomes a necessity, not an accessory.

Susan Cummins: Please tell the story of how this exhibition and the related publication, On Body and Soul: Contemporary Armor to Amulets, came into being.

Suzanne Ramljak: In studying jewelry’s functions over the years, I have come to view its protective role as perhaps its most compelling. This ancient and universal dimension of jewelry addresses our essential vulnerability and attempts to overcome fear and uncertainty through wearable ornament. The ability of adornment to empower and safeguard wearers also stands in opposition to common notions of jewelry as merely decorative; jewelry in this context becomes a necessity, not an accessory.

I was particularly interested in the ways you describe the difference between the amulet, the talisman, and the charm. Can you talk about the differences here and use an example of each from something in the exhibition to illustrate these differences?

Suzanne Ramljak: The terms “amulet,” “talisman,” and “charm” are often used interchangeably. All three forms of ornament are faith-based, what I call “protective software.” While there is no solid proof that they will achieve the desired ends, they are designed with slightly different aims in mind. Generally speaking, an amulet is a repellent device worn as a preventative measure against harm or misfortune. Talismans are more proactive, usually tailored to specific purposes, and can either safeguard a wearer from danger or garner good fortune. Charms primarily court good luck and happiness rather than deflect evil, thus the expression “lucky charm.”

Regarding contemporary examples, I want to stress that I only included works that the artists themselves identified as amulets or talismans. I confirmed the intent with the maker first. You will find a wide range of protective amulets in the exhibition, from David Bielander’s silver Garlic pendant to Nancy Worden’s Lunar Phase Amulet. Elissa Franco’s Your Own Worst Enemy amulet is meant to protect against self-sabotage, containing written affirmations that can be read to combat self-defeating thoughts. As for a talisman that seeks to secure goodness, there is Lorena Lazard’s Spinning Heart, a pendant featuring a fenced-in turning heart that evokes moments of happiness, according to the artist. And a prime example of charms is found in Nancy Slagle’s Fertility Bracelet, which solicits luck for the wearer through iconography relating to procreation and pregnancy.

Suzanne Ramljak: While certain factors remain constant over time—the human desire for health, love, wealth, social cohesion—there are now new threats against which we seek to protect ourselves. Instead of attacks from animal predators, we must contend with gun violence and bombs. These new dangers are reflected in the materials and imagery of the amulets within the book and exhibition. For instance, Boris Bally’s Brave necklace is made of gun triggers instead of the bear claws once worn by Native American warriors. And today, rather than arming ourselves against physical attack, we must guard against invasions of privacy and personal integrity from technology and surveillance. In the book I quote designer and computer engineer Steve Mann on the threatening encroachment of cameras and computers: “We live in a world in which the appearance of thugs and bandits is not ubiquitous,” Mann says. “Surveillance and mass media have become the new instruments of social control.” Accordingly, a number of works showcased are directed at technological forces and pervasive means of surveying our behavior. Again, one of the virtues of this project is the prescience of these artists in addressing the pressing issues of our era, which has rightly been called the Age of Terrorism.

Suzanne Ramljak: As I worked on the book, one thing that became clear was that any piece of jewelry has the potential to protect and fortify its wearer. The very act of donning jewelry can boost our self-assurance. We all know that beauty is a form of power. And money, as embodied in costly materials, is also forceful. Much jewelry serves as psychological reinforcement or mental battle gear, preparing us for power struggles and symbolic showdowns. In this, a strong “captivating” piece of jewelry can disarm a viewer just as readily as a traditional amulet.

That said, I have a couple pieces that are almost guaranteed to capture attention and then undo onlookers. One is a miniature mother-of-pearl folding knife by the renowned Italian knife company Maserin. I wear it as a short necklace and it looks like a lovely, gleaming ornament against my skin. When people see I’m wearing a little weapon they are taken aback. It generates the perfect combo of charm and discomfort. I also have a silver ring with a lifelike blue eyeball, which serves as a trap for the evil eye. It functions on the principle of distract-and-conquer.

These pieces can be powerful, sometimes in a creepy and scary way. How do they acquire that power?

Suzanne Ramljak: Within the practice of defense, instilling fear and awe in one’s opponent is certainly a useful tactic. Scary and creepy become aesthetically strategic for unnerving one’s adversary. In some cases, this unsettling power is generated on a visceral level, through the materials and forms enlisted. We are hard-wired to respond to sharp and jagged things—like thorns or blades or spikes—that could actually tear or puncture our flesh. In other instances, we may be responding to items or symbols that we have a personal predisposition to dread. The force and power of an object (or person) increases in proportion to our own fear and weakness.

What pieces are the most powerful and intimidating in the show? Which have the deepest strength of protection?

Suzanne Ramljak: This gets back to the subjective disposition of the wearer and beholder. Intimidation is largely dependent on one’s vulnerabilities. For men, Ira Sherman’s Injector Anti-Rape Device might strike the greatest dread through their hearts and groins. If you have a particular fear of sharks, then Aliyah Gold’s Shark Teeth Necklace would be especially off-putting. Then there are pieces that could cause serious harm and deserve to be feared, like the various brass knuckles on view or works with porcupine quills or other sharp protrusions.

What books or references were most helpful to you in understanding what makes an object a powerful protector?

Suzanne Ramljak: There are a number of historical and ethnographic studies of such apotropaic ornament, and I tried to read most everything published on the subject. Among those, I found value in Wallis Budge’s Amulets & Talismans; Sheila Paine’s Amulets: Sacred Charms of Power and Protection; and Migene Gonzalez-Wippler’s The Complete Book of Amulets and Talismans. Because the literature on the subject is vast, I had to keep reminding myself that I was writing a contemporary art book, not a cultural survey of amulets. I also found it useful and engaging to research the dynamics of belief, superstition, fear, anxiety, and even placebos, all of which I touch on in the book’s essay. The power of protective ornament, as with most jewelry, derives partly from material properties and in larger part from the values and willful beliefs that we invest in these objects. There is a crucial and fascinating psychological dimension at play here that I intend to probe further.

Thank you.