In July 2012, Dutch-born jeweler and educator Peter Deckers sent me an email. He had launched a mentoring program a year before, independent of his teaching work at Whitireia (Wellington). It was shaping up nicely, and would lead to a publication to be released the following year in Munich: Would I write about it? I could check the website, which served as diary and billboard for the mentee/mentor exchanges, he said; it was full of things.

“Full” did not even come close to describing the depth, variety, and extreme commitment that this project elicited from participants: numerous entries, spanning 16 months of tutoring, were but just the tip of a mountain of unwritten, unrecorded experiments, discussions, images and reference swappings. I dove in, and never looked back.

Now in its third session, Handshake (HS) has gained in repute and international standing: the educational model it provides, a mix of jewelry Ivy League and boot camp for the aspiring professional, pays homage to Greek pedagogy as powered by modern connectivity, and has yielded some impressive results. I caught up with Peter a few weeks after the opening of the latest HS show at Objectspace, in Auckland.

Benjamin Lignel: Peter, I’ve been “following” the HS trail for a while, and I’d like to make sure that this interview gives that complex project its due, and tracks its evolution from “crazy idea” to “established international program.” At the beginning of the project, if I remember well, was a disillusion: You were fed up with seeing promising graduates from Whitireia getting tripped up by “real life.” Did you think then that this was a problem specific to New Zealand, which required a specific remedy?

Peter Deckers: Through several conversations with colleagues in education around the world, I can say that this problem occurs in countries that operate education as a core business—in England, Australia, and New Zealand—where a degree can be achieved in three years. Longer study will be unaffordable for most. The high fees force students to make choices. I noticed with the visual arts program at Whitireia that students get more competent during their third year. However, after their graduation, I have seen highly talented students drift away from their experimental practice: They may bow to feedback from an ill-informed peer group, or to financial pressure, and start producing work that sells so they can pay off their student loan. This problem may be specific to countries with expensive higher education. In contrast, jewelry studies in Germany are free, and offer plenty of options for higher education. The Handshake project was conceived to provide New Zealand graduates with a pragmatic post-diploma program … but I can see that the project’s diversity and opportunities could even benefit a well-educated, German-trained artist.

Who were your allies, and what were the challenges standing in your way back then?

Peter Deckers: Back in 2010 I was asked by Bridget Kennedy of Studio 2017, a Sydney gallery, to curate an emerging New Zealand artists’ exhibition, to open more than a year later. I worried that some of the selected makers could fall into the trap I just described and thought they could benefit from feedback by a mentor, so their “experimental” practice could continue and not spin into surprises. I asked those selected who were their three “heroes” … and I basically began a process of matchmaking. Some of the mentors I knew, but most were famous entities that I knew only from books, the Internet, and/or catalogs. Most mentors I contacted were more than happy to mentor emerging artists. I discovered that the more famous role models had never or rarely received a request for mentorship, which surprised me.

I was helped, here in Wellington, by Karl Fritsch, who knew many of the prospective mentors and/or suggested alternatives to those who refused. All the Handshake1 mentors took on their mentorship with no pay, with the promise that I would try hard to find funding, which worked out well at the end. After the Sydney exhibition, Creative NZ started supporting the project financially, we got several other exhibition offers, and the Handshake project was born. This mentorship was only meant to be for that one exhibition, but word spread quickly (i.e. through the website and by word of mouth) and other exhibition offers kept on coming. We just continued, shaping it into what it is today. (Please see this short video for the HS background.)

Applicants who passed the HS1 selection process signed up for a mentoring program 18+ months long with an artist (almost) of their choice. The program promised to give them plenty of opportunities to exhibit work, but was also largely self-driven. What educational/training models did you have in mind when you conceived the program?

Peter Deckers: The pedagogy is based on the old apprentice model, adjusted to focus on the mentee’s needs. With so many good makers around the globe, and technology that allows you instant access to everyone and everything they do, we now have the benefit of choice. This “choice” is important: Matching the practice of the selected mentees to their mentor’s interest is the strength of this program. Each mentor looks at the portfolio of their potential mentee before teaming up. For the first time in history, the continuing “student” is not prey to the random local educationalists, but is connected with somebody, within electronic reach, who has similar or complementary interests and shares their love for object-making. It should be a reciprocal interest, where mentors learn from their mentees. We have seen that happening over the years.

Tell us about the team behind HS, and the support system that it lives on. Were there moments when its survival was in jeopardy?

Peter Deckers: We have a wonderful support team, working within the Handshake ethos.

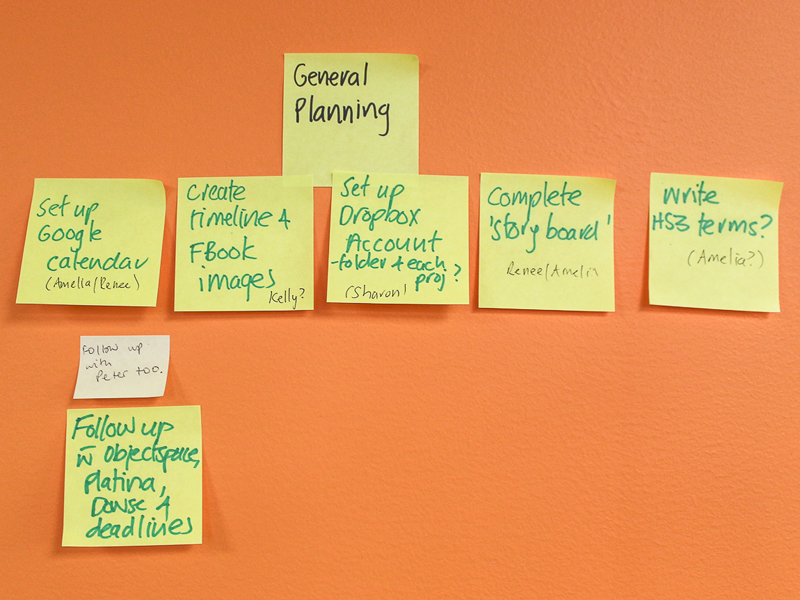

I equally learn from my own students, and from the HS participants, who all come from diverse working/knowledge backgrounds. My partner, Hilda Gascard, and I manage Makers101 Ltd, the legal entity that deals with the creative and project management of the Handshake Project, and with its finances. We are supported by our advisory team (A-Team) for the strategic planning of this project: editors, proofreaders, graphic designer, and Whitireia staff, who are most supportive of my HS research. Each new Handshake project has an appointed/independent selection team/selector, making up the participation selection, as well as temporary, project-specific advisors: The Dowse Art Museum curator Sian van Dyk, for example, supported the HS3 artists in the development of their exhibits in that museum (to be shown in August 2017). Each HS group comprises people with specialized skills (digital, technical, etc.), and the ethos behind Handshake is to share that knowledge, to support and to nurture leaders beyond dependency. The project has until now not been in serious jeopardy: Supporters have always jumped in when needed, to help bring a particular HS event to completion. However, fundraising is becoming crucial to complement the income from our funding agent and stay afloat—as is expected in any business activity.

One of the key factors in HS is the matching up between mentee and mentor. One of the ways to characterize your choices is a form of “judicious mismatch”: In other words, making sure that there is enough tension between mentee and mentor for it to sizzle in the right way. But maybe this is just in my mind. How would you describe the process and challenges of pairing an applicant with their “idol”?

Peter Deckers: What has become apparent over the last five years is how serious the mentees took their Handshake project challenge and how much time mentors tend to allow for it. The selection team needs to have a good knowledge of the sector and of the mentor’s practices, what their focuses are, how they communicate, and if they will match the mentees’ interest and vice versa. This interconnection is the strength of the program and is the key to getting it right.

But there will always be an element of chance in this “match-making” and what happens afterwards: How each relationship unfolds is up to each pair, complementary or not. I have seen mentor/mentee practices develop into a healthy partnership, but also a few disintegrations. Mentees have to learn and work around their busy mentor’s schedule while fulfilling their own duties as mentees: finding out ways of communication, inspiring the mentor, preparing each mentor session with questions and topics. Being purely subservient to a mentor will definitely not work in developing a respectful, creative, sparkling relationship. They have to develop the professional assertive skills that they will need in their own professional practice later on anyhow.

One of the worries you had early on was that the emotional pull of the mentor could be too strong, and mentees would struggle to find their own voice at such close proximity to someone they admire. How did you deal with that, and do you find that this is a weakness of the setup?

Peter Deckers: That definitely is one of the big challenges mentees face. The selector(s) need to weigh carefully the mentee versus mentor practice so that a common ground can be found between them. Some mentors have big-ticket fame status and mentees occasionally get a form of stage fright. Working with your “hero” can go in a multitude of ways. It is hard to say how that unfolds in each case, but Handshake functions like a protective “umbrella” project: slip-ups in experimental practices are allowed to happen.

This is another strength of the project: Feedback tends to irons out those slip-ups. It could be feedback from one’s mentor, but also from the group of mentees itself. Their bond is incredible. The mentor “trick box of tools” or their “shortcuts” might be shared or not, but what the mentee does with it is what matters. Conversely, the emotional pull from their mentor allows mentees to confront things they would not confront otherwise. Imitation or copying hardly happens, but if it does it is mostly at the start of each project. So far we have seen very few unpleasant surprises and most of the mentees have grown into respectful artist/colleagues, and a few maintain a healthy friendly relationship with their old mentor.

I did worry that strong mentors could take hold into the core fixations and interests of their mentees, confusing them without meaning to. That is why I developed an extended version of HS project called HS3, where the mentee is without a mentor and acts as an independent “artist” where their former mentor (potentially) becomes their collaborator. This independent focus works well for the development of becoming “international-exhibition ready.” Art graduates often have to fight off school influences and my thinking was that it also could be the case with a strong mentor relationship. My assumption was that to make the mentor into a collaborator, some sort of equality needs to happen first.

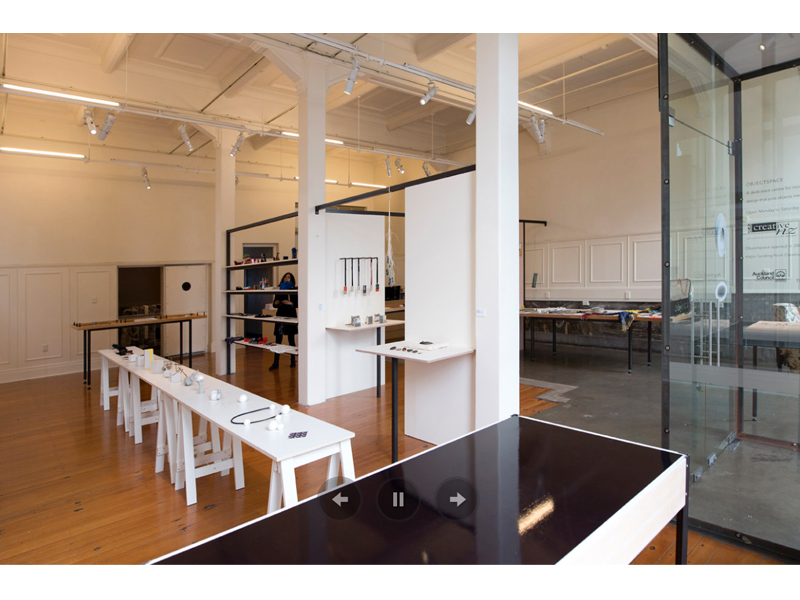

One of the high points of the HS program was the mentees’ exhibition during Munich Jewelry Week 2016. I loved the diversity and depth of the work, and thought the simple and effective display supported that diversity very well. What did you take from that show?

Peter Deckers: That show was such a highlight for most who came to Munich. I personally faced the challenge of negotiating the space of the Munich Residenz Palace, designing/ making its furniture and lights, negotiating the budget, organizing the freight, negotiating the limited amount of time for setup, organizing the catalog … and making sure that my curatorial plan worked. In the end it all came together nicely, thanks to the efforts of a whole lot of people.

Munich has always been a big pull for jewelry artists, and exhibiting there during MJW makes networking and dialogue easy. A number of opportunities came out of that trip: We negotiated a book deal with Arnoldsche Art Publishers, hatched a plan for a future international exhibition, worked out collaboration options with the creative London-based group Dialogue Collective (planned for MJW 2017), organized artist/education exchanges, and met curators, collectors, other colleague educators, and makers. In March 2017 we will be back with a HS3 exhibition at the Handwerksmesse (Frame galleries), not unlike what we had in 2013. The curatorial team this time will be Liesbeth den Besten, Sofia Björkman, and myself.

Simply learning to work with others is a huge takeaway for HS participants, as Kim Patton points out in her exhibition essay. This state of constant exchange and negotiation stands in sharp contrast with the solitary figure of the studio maker. Does this emphasis on sharing have to do with your views on authorship, or the skills needed to work in the 21st century?

Peter Deckers: The world is getting more and more interconnected, and to do well in it, we need to work together. We are far from ready, but initiatives like HS are a means of making that possible. This project is not for the fainthearted. It is not a project for egomaniacs or prima donnas, but more for those with an open and sharing mind who are not afraid to open up for artistic experiences and creative adventures.

Thanks to your tireless fundraising efforts, HS has had three iterations. Where will you be taking it next? Is there a temptation to turn it into, well, a permanent thing?

Peter Deckers: There is funding from Creative NZ for two more projects: HS4 and HS5. HS4 was an open call for a new group of New Zealand jewelry makers (one year or more out of their art study); its deadline was October 10, 2016. Ruudt Peters will be the “independent” selector, with the task of finding and matching potential mentees with the practice and personality of the chosen—or recommended—mentors. Tanel Veenre from Estonia will do the HS4 masterclass, and there will be several new national exhibition challenges. Atta Gallery in Bangkok and Pataka Art + Museum in Porirua, New Zealand, will host HS exhibitions with selected HS alumni in 2018.

At this stage, HS5 (2019–2020) is supposed to be our last project, with 12 members selected from the previous HS projects. Their challenge will be to make work for one international and one national museum exhibition. How that will unfold is still under discussion.

After six years, the HS model seems to work quite well. It is the missing link from higher education to professional life, and could easily be “the” alternative “hands-on” program to the conventional master’s degree. I do hope that it can become a practical educational model for (other) craft arts media. It needs proper funding, but just as important is the person who will lead it, and the practical knowledge, network, and commitment they bring to the project. It won’t survive a simple cut-and-paste operation.

Note: Given the collective nature of Handshake, photo provenance was sometimes difficult to ascertain. Our apologies if some images have been wrongly credited.

INDEX IMAGE: The Handshake3 mentees’ group photo, Wellington, February, 2016, photo: Kelly McDonald