Looking at the work of artists from a wide range of practices—artists like Yuka Oyama, Rachel Timmins, Lucy McRae, or Nick Cave—there seems to be a surge of interest for deploying ornamentation, or body art, over the whole body of the wearer. This phenomenon blurs the distinction between jewelry and fashion, but also between traditional costumes and anthropomorphic fantasies. It seems undeniable that artists are being impelled by a desire to make their works evolve and mutate toward something more audacious, bolder, and less rational in order to free the body from its conventional physical aspects. The body can then reach a more symbolic—playful or iconic—dimension. This article is mostly focused on jewelry designer and milliner Maiko Takeda, who launched the remarkable collection Atmospheric Reentry in 2013, during her MA graduation from the Royal College of Art in London, and who I interviewed this spring.

1. Abstraction of the body

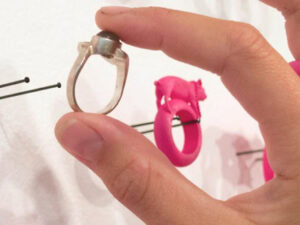

The ingenious technique Takeda developed consists of the layering of printed clear film, sandwiched between acrylic discs and linked together with silver jump rings. The process is meticulous and time-consuming; the result resembles an organic and effortless collection of futuristic headwear and other body pieces.

Her work illustrates the versatility of a type of adornment that is hardly definable as it combines multiple aesthetic references. Takeda explains that she aimed to “create a visual effect of intangible aura”—while searching for a way to translate the sensation given if someone would “wear a cloud.”

As a milliner, she sees the head as “an extremely powerful part of the body to adorn,” but adornment is not exactly what she intends to do. Instead, she subtly disturbs the normality of the face by submerging it under a thin—and yet imposing—mask of spikes. Takeda added that “by covering the face it can transform one’s personality, or by putting a crown it can instantly symbolise the power and status.” Like Ana Rajcevic’s Animal: The Other Side of Evolution, these pieces enable the mutation of the wearer’s facial features. The human presence is being abstracted, transformed by the futuristic appearance of either the ethereal cloud (Takeda) or the sophisticated yet brutal growth of animalistic bones (Rajcevic). Both works involve the human features being empowered by the worn pieces.

Meanwhile, Lucy McRae’s and Bart Hess’s (LucyandBart) images depict their mutating selves in a much more experimental format—their photographs focusing on the change they bring to the silhouette itself, and less on the objects or made-up costumes worn, which tend to be ephemeral, and seem to be accessory to the photograph itself. The oversized body-pieces are hybrids that combine the visual languages of more vulnerable materials as various as foam, paper, half-inflated balloons, or cardboard. When worn, their relation to the body reinforces the complex role they play: making the audience open up its conception of what is real and plausible. These body extensions have in that sense the function of giving a more tangible expression of a dream or an ideal and to communicate it to the audience—which can more easily relate to the haptic sensation of the model wearing the costumes when seeing them being worn.

2. Set in motion

Another example of uncommon costumes are Nick Cave’s Soundsuits: The wonderfully colorful and tactile costumes express the joyful and liberating influence of movements for a full audience. The dance isn’t subordinate to the costumes. It completes them during live performances and processions that combine sounds and movements: The bigger the motions, the more impressive the costumes get, and the fine artist’s and dancer’s parades are an extraordinarily festive explosion of expressiveness. When the creatures roam through the streets, they in fact refer to many lost rituals, such as the European costumes photographed by Charles Fréger in Wilder Mann, which were initially meant to domesticate fears and celebrate the natural cycles of the seasons. Most of these rituals have disappeared or took a more sophisticated form through time, but the Soundsuits share the same primitiveness. Cave brings this idea of folklore back to our current urban surroundings.

While Takeda’s practice is more clearly rooted in the production of wearable—and sellable—objects, she shares with Cave an interest for staged performance. She recalls that the creation of Atmospheric Reentry coincided with the revival tour of Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach, in 2012: “I was totally blown away by its futuristic mood of the sound and imagery and this became a parallel influence on the aesthetic of the collection throughout the development.”

To see the jewelry/costume in movement, worn by someone, emphasizes its belonging to time; it can become ephemeral if worn during a unique representation or keep an unfading glow if documented as a video. Photographs show how the pieces fit on the body and leave the rest up to the imagination of the audience; they can be static like Takeda’s, or express the idea of motion as in LucyandBart’s. Videos, meanwhile, can influence and reinforce other characteristics, such as weight and movement, that make the perception of the object much more explicit, as in Cave’s filmed costumes.

The choice between different means of representation is therefore crucial for the understanding of these body-pieces, more so than for conventional jewelry.

3. Personal appropriation of the surroundings

Takeda is interested in manipulating textures on the body and commented that while studying millinery, she felt restricted by the traditional materials for headwear that are normally tactile, tangible, and durable, such as felt, fabric, plastic, and lace. She had a different concern: blurring the boundaries with the surrounding environment through her headwear.

A recurrent word in my interview of the Japanese artist was “etherealness.” “Growing up in Tokyo in the 80s/90s when the bubble economy collapsed,” she explained, “my generation didn’t have much obsession with materialistic lifestyle like my parents’ generation did back in the 60s/70s. This is probably one of the reasons why I tend to go away from physical materials that will eventually get old and age, but more focused on things that are ethereal and experiential. Also it is part of the Japanese aesthetics to find beauty in intangible and aerial elements in our natural environments, such as cloud, shadow, and wind.”

Takeda’s specific cultural background informs a sensibility that seems to be having a global moment. We find it in the previously mentioned LucyandBart, video artists Lernert & Sander, the collective of artists/designers We Make Carpets, fashion designers Femke Agema or Hendrik Vibskov, performer Francis Alÿs, or installation artists Christo or Olafur Eliasson. It is a rather common wish to focus on the sensorial experience and to find ways to deal with the impermanence of things. These artists’ emphasis is often set on creating and communicating a whole range of sensorial experiences through art installations and performances.

When creativity lies in finding the potential in our given context, there are plenty of ways to appropriate the materials that surround us. Whereas Takeda seeks to avoid any reference to materialism in her creations, the artist Yuka Oyama embraces it by bringing everyday objects into play—and giving them the main role—in her works. Oyama recently presented the series of performances Cleaning Samurai and Stubborn Objects Psycho Drama, which animate wearable art costumes. These videos relate to the use of all objects surrounding us daily.

Our relationship with materiality and technology is constantly changing and, by putting actors under the skin of objects like vacuum cleaners or a set of keys, Oyama questions the bond between people and standard objects with a sharp, personal sense of humor. It might also be a nice allusion to the “objects with a soul” concept, as in the Japanese most-traditional style.

Takeda, Oyama, and most of the artists referred to in this article work by hand in the creation of their costumes, and, even if the artists have a varied commitment to crafting techniques, their wearable art-pieces all capture a single personal form of artistic expression. They tell a full story thanks to their materiality, relation to the body, and the chosen way of representation—unworn, occasional performance, photographic or filmic representation.

About the ambiguous reference to technology in Atmospheric Reentry, Takeda specifies that she wanted to keep something tactile and analog about the pieces. She didn’t want to use LED lights or anything with a motor or battery. The effect is that they look somehow digital, but the point was they were all made of the tactile and low-tech materials around us.

The assimilation of industrial materials in her designs underlines her observation that the technological realm currently belongs more to our natural habitat than to nature itself. New intertwinements between nature and technology are being found since our relation to nature itself is in mutation. The oversized body-pieces might constitute a way to feel directly confronted by industrial materials and to find beauty or interesting features in them. This type of adornment can be considered as an attempt to redefine our relation to objects, materials, and the nature surrounding us.

Conclusion

The suits/overalls/body-pieces/oversized jewelry pieces/covering adornments/experimental costumes/body ornamentations/new body extensions are hardly definable by a single word because they are so versatile: They all had different reasons to originally be expanded on the body and do not all belong to the same category of object.

The keen interest in the growing number of body-pieces can be explained by their mediating role between people and their mutating habitat—we might feel like we have to adapt and mutate, too, in order to redefine our place among things.

Sometimes the costumes revive old rituals that include dancing or dressing up, sometimes they project us into a futuristic or fantastic dimension, but they are always hybrids, in-between objects that need to be worn and/or documented to fully exist.

While the imagery of the fashion industry is largely accessible, these types of creations appear as a way out from the conventional standards of beauty and offer a means of expression on an individual scale—by putting fashion photography and video at the service of more alternative, experimental, and stylistic art forms.

The postures, allures, and movements of the wearer therefore add to the full picture of the artwork, to its narrativity and to the atmosphere it conveys; they become factors that the audience will read to appropriate the sensorial experience(s).

Contrarily to jewelry, which mostly needs to tell a story on its own, the creators of these other expanded pieces explore their common ground with the fields of theater, fashion, performance, and photo/video to tell their story.

Much as with a superhero whose costume gives him superpowers, these body-pieces are a complementary garment to the ordinary human figure and its normal abilities. They are powerful objects that carry a singular vision and/or atmosphere and share them with both the wearer and the audience.

INDEX IMAGE: Maiko Takeda, Atmospheric Reentry, 2013, headwear, plastic film, acrylic, silver, dimensions variable, photo: Bryan Huynh