Nellie Peoples and Zoe Brand are emerging art jewelers who have recently graduated and are exhibiting together for the first time at Bilk in Canberra, Australia. They are both concept-driven jewelers examining parallel themes: the connections and dialogue between objects and people (Peoples), and how we consume and understand signs, extending the dialogue to the wearer, the object, and the viewer (Brand). Here we caught up with them on the eve of the opening reception.

Bonnie Levine: First of all, congratulations to you both on your recent graduation from the Australian National University, School of Art Gold and Silversmithing Workshop. That’s very exciting!

Nellie and Zoe, even though you’re exhibiting solo bodies of work in the Bilk show, why did you choose to exhibit together? Do you see any parallels in your work?

Nellie Peoples: Since our time studying together, I feel Zoe and I continue to investigate the two sides of the same area of exploration. For example, what drives the desire to wear and own jewelry, and how can that be brought to light? We investigate these similar questions and concepts from completely different angles. In this way I think of both of our pieces as “conversation starters” across a number of registers, namely with the viewers and potential wearers who take the objects with them, sometimes none too subtly, whether there is a suggestion through the form or the objects literally spells it out for you. I enjoy the way our work complements one another. It makes the conversations between our pieces exciting and this dialogue pushes these concepts open for a broader discussion.

Zoe Brand: I think it was natural that Nellie and I would eventually exhibit together. While in the workshop at university and over numerous beers and ciders afterwards, we would often chat and muse over how we were interested in many of the same overarching ideas (as Nellie mentions above) as well as exploring an active engagement or participation with a viewer. It seemed like perfect timing when Bilk suggested we show together and I’m really excited to see how it all comes together in the gallery.

Nellie, tell us about your background. How did you become interested in making jewelry and objects?

Nellie Peoples: Since childhood I have always been a maker and a destroyer. I made objects and forms, but that usually came at the cost of taking something else apart … unbeknownst to my parents.

My formal education began in architecture, so I was introduced to the field of design through a focus on user- and human-centered design. Although I enjoyed architecture, I didn’t find my place there. It wasn’t until I visited Australian National University, School of Art Gold and Silversmithing Workshop that I realized that was where I wanted to belong. I had an insatiable curiosity how a material such as metal could be manipulated so incredibly. Through my architecture degree, metal was introduced as an unwavering material; conversely, in the Gold and Silversmithing Workshop, it was the starting point of play.

How has your background in design and architecture shaped and influenced your work?

Nellie Peoples: The transition from design and architecture to making jewelry was surprisingly smooth. There is a distance between the two fields and at once a closeness that can inform each discipline. I think, fundamentally, both fields are based on the human form, human scale and the unique cultural phenomena brought about by human interactions with modes of materiality. For both disciplines, people are the center around which the form is built. However they are also an element with which the form, for instance a building or a ring, interacts. My work examines how humans interact with the form with a focus on creating a “space” for this interaction. I also push this idea where possible to explore how humans might come to inhabit the form in various ways.

A central theme of your current work is the connection between an object and people—that a jewel is both tangible and intangible, and it bears witness to the wearer’s experiences. What does this dialogue and interaction mean for you, and how is it expressed in your jewelry? Have you personally had such a narrative with a piece of jewelry?

Nellie Peoples: For me, jewelry is dialogue and interaction. It is this aspect that excites me about jewelry as a creative field. I see it as a surface for conversation.

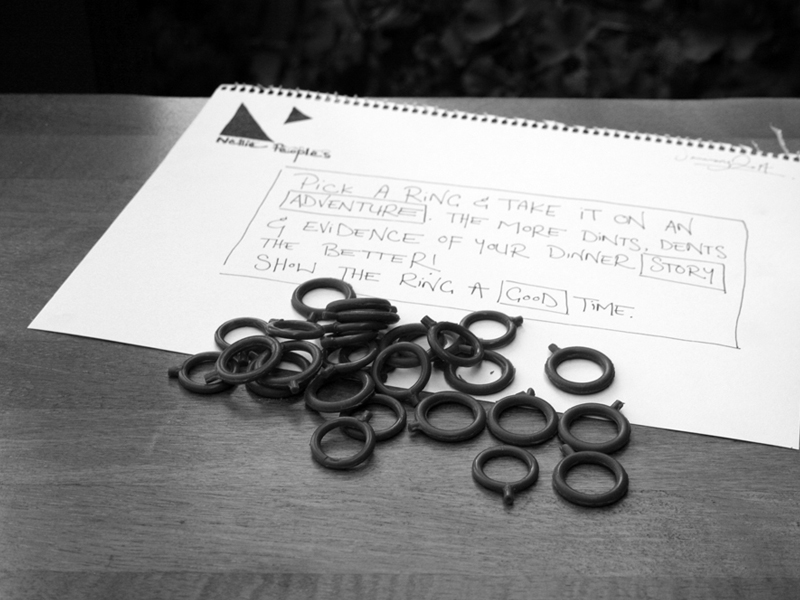

In the spirit of full disclosure, I must confess that in the works I am most proud of, I’m not the sole source of the work’s expressivity. In my series Souvenir, I instigated a happening where the participants were invited to wear a wax ring for the duration of the event. At the end of the happening, the wearers removed their wax rings and then the rings were cast in metal to capture the journey between object and wearer. This process worked to make concrete their mutual transformation whilst at the same time celebrating the parts of this transformation that will always remain intangible and invisible. The rings became a souvenir of the event. Each ring was as individual as the wearers that belonged to them. The wearer’s character was written, dented, and scratched all over the surface of the ring. I designed as blank a canvas as possible, so to speak, and then eagerly watched the transformation through the complex interaction.

These kinds of narratives of presence, co-presence, and lack of presence find an origin in my grandmother Una’s wedding ring. She passed away many years before I was born, so all I knew of her were the stories told and this ring that my family had inherited. When I was very young there were special times I was allowed to hold and examine the ring. The main feature that caught my eye was that the interior of the ring band was worn so sharp from being donned for so many years. It was like a razor’s edge, so sharp in fact that it couldn’t be worn by anyone else once it was taken off her hand. It was a bittersweet thought that always stayed with me. I have been lucky to have this narrative with a piece of jewelry. It’s unique. This kind of connection is not possible with every piece of jewelry. So my work often returns to why that is and how these connections can be made or, simultaneously, erased—or not made at all.

Your work is very much about line, precision, and structure. How does this manifest itself in your designs and your process of making? Do you ever take a more organic approach to your jewelry?

Nellie Peoples: Line, precision, and structure, as well as the making process, were definitely developed and refined during my time in architecture. A rigorous design process and design thinking were highly encouraged. This became a platform upon which to build when I began my jewelry practice. There is a constant to and fro between drawing and sketch modeling before an object is made. I think I also conceive of this process as inherent to the journey of the object and so I take a great effort to document my stages of conceptualization, theorizing, structuring, and experimenting.

But as the daughter of a scientist and an artist, I believe there is a compelling organic approach entangled in the geometry of my work. My work begins from what may be perceived as a structured architectural shape but it is then expected to catalyze a very organic and unpredictable interaction. This is what I would define as the organic approach in my work: starting with a hard-edged geometric shape and following where others take the idea and/or concept, as was the inspiration for my recent Souvenir series. The objects do not have the kinds of lines and shapes we expect when we talk of an organic aesthetic, but when I create the objects to be part of the co-creation of meaning through a very physical process of change then I feel the approach becomes more organic. I do believe this space, the in between, is where the interesting forms and conversations evolve.

You’ve said that the machine adds to construction rather than drives construction. Can you elaborate on this notion?

Nellie Peoples: My design and making process begins with drawing and sketch modeling. The form is designed and then the machine, if one is used at all, is decided upon. It is used as a tool to achieve a desired result, rather than a driving force in the decision-making. I work in a kind of call-and-response mode between sketching and working by hand at the bench. Following my sketches, the forms are created at the bench first. I can feel the materials and respond to them intuitively. The bench and bench skills are of the utmost importance to me.

In your new body of work, you’ve made a series of rings covered in crayon. What is your expectation of how the wearer will interact with the ring, and what do you hope they take away from the experience?

Nellie Peoples: My expectation of the crayon-covered rings is that they be a catalyst for thought and conversation. My hope for the viewer/wearer is that they respond to the desire for exploration and the feeling of curiosity that is too often trained out of us over a lifetime. I want them to break with the expected socio-cultural norms of gallery spaces and interact with the object and in some ways destroy it. This of course harps back to my beginning life as understanding destruction as a texture of construction. The objects will become richer for their participation. The viewer/wearer would take the ring on a journey and this concept in my work is played out in a literal way as they “map,” more likely scribble, across the page/table in front of them. The “journey” in this sense is made visible but in doing so allows the wearer to think about the in-visible. The crayon is used for its mark-making capacity that reminds us of a sense of play and potentially mischievous play. Here I am thinking of coloring between the lines at school and scribbling on the wall as a kid.

In the process of interaction, the crayon will wear down as a consequence of its tracing a journey onto its surrounding environment. As the object is worn, the ring begins to reveal something of itself to the wearer; it wears away its skin to reveal something more beautiful. This example is a literal translation, but I hope to prompt thought of the wearer’s own narratives that are told on the surfaces of their precious pieces of jewelry. It is a playful and complex exploration of the relationship between the wearer, the object, and the time and space that surrounds them both.

This focus on user experience, and having an object bear witness of the passage of time by consuming itself, is a pretty powerful proposition. Is designing “nearly disposable” rings a form of critique of preciousness?

Nellie Peoples: My intent is not necessarily a strong critique of the concept of preciousness in materialist terms, although the work certainly invites that reading. Rather I hope to add to the conversation surrounding the concept of preciousness in the everyday. The work aims to open the concept of preciousness so as to build upon, and expand, the boundaries of what counts as precious. The work asks how we might perceive of preciousness in everyday life. What might happen if we were to include not only the object, but the narrative that is forever attached to the object? And, by narrative, I mean to reach beyond the classic idea of the provenance of an object that deems it to be culturally precious. I mean to pull it back to a very specific and personal narrative and history of/with an object which, to me, is just as precious as the object itself.

In some ways the subjectivity of such an experience lends itself to a preciousness in that it can never be fully grasped, theorized, or explained, making it all the more exciting. I want people who interact with the works to sense what I sense about jewelry in that these kinds of narratives are the souls of an object. I want them to ask if an inanimate object can have a soul. The story of coming to know my grandmother through a ring, as though she were in the ring, has become just as precious to me as the ring itself. Both can survive beyond the other, but together they are truly powerful.

Zoe, how did you get started as a jeweler?

Zoe Brand: Back in the days when the government thought it was important to fund the arts, there were more galleries supporting art, craft, and design. It was one of these now-defunct galleries that really opened my eyes to what jewelry could be; it was far more interesting than what I had encountered previously. I enrolled in a short course and then on to full-time study, and immersed myself into the field by making, writing, and curating exhibitions, and have been doing so ever since.

You’ve said that jewelry is one of those things that people inherently understand—how and when to wear it, where to buy it, how to give it, etc.—except when it comes to contemporary art jewelry. What do you mean by that?

Zoe Brand: I would say for the most part that contemporary jewelry doesn’t really look a lot like what most people would understand to be jewelry. It’s often larger, occasionally unwieldy, and made from questionable materials, or questionably made from traditional materials. It requires boldness of its wearers and pushes the boundaries of our inherent understanding of it. This is what makes it so exciting, but also what can be challenging to an uninitiated audience.

It’s funny, I speak with art gallerists about jewelry as an art form, as a means of translating a concept in relation to the body, but even though their profession is to deal in ideas they rarely get past a traditional notion of what jewelry is. To be fair, jewelry has such a profound history that it’s a hard act to follow. Its understanding is so imbedded in culture that it might always be a struggle for contemporary art jewelry to break down the traditional notions and to be seen as something other than or more than just a pretty thing to wear.

In 2013 you started Personal Space Project—an online gallery that also exists in the most personal of spaces, your bedroom. Tell us about your gallery and why you chose that location. Is it a commercial venture or a venue to explore ideas? How do you choose exhibitions? Does it still exist?

Zoe Brand: That seems like a lifetime ago. I had recently taken a sabbatical from being an adult. I had returned to studying and moved back in with my parents, which surprisingly freed up a lot of headspace and allowed me quality time to really think about my practice. I have always wanted a gallery, but the work I wanted to show was never going to make rent. I thought the most reasonable approach was to have a gallery with so little overhead that I didn’t need to sell anything to make it happen. It just needed a lot of gusto and a bunch of willing participants.

So I set up the Personal Space Project along one wall of my bedroom. It performed the role of a traditional gallery with catalogue essays, floor sheets, numbered works, and was open to the public (by appointment) and available online 24/7. It was really important that it be physical space, not just images of work on a screen. I wanted the audience to get a sense of the scale of work in the “gallery” even if they were on the other side of the world.

It was also really important to me that I exhibit artists whose practice or work didn’t necessarily fit in a traditional gallery or jewelry gallery setting. I feel so privileged to have experienced particular work by artists such as Manon van Kouswijk, Bridget Kennedy, Volker Atrops, Sharon Fitness, Lauren Kalman, Mel Young, and Renee Bevan + Jhana Millers, just to name a few. These artists required me to switch on, recharge, activate, perform, and even literally bathe myself in the work, which at times was challenging but also such a rare and gratifying experience.

The Personal Space Project is currently on an extended hiatus after running for two years. This was mostly because of the increased intensity of my study as well as moving in with my boyfriend, after which the bedroom was no longer my personal space (also the bedroom walls were green). It may in the future come back to life in a different form, but for now it is just a pleasure to look back at all that hard work and experience and reflect.

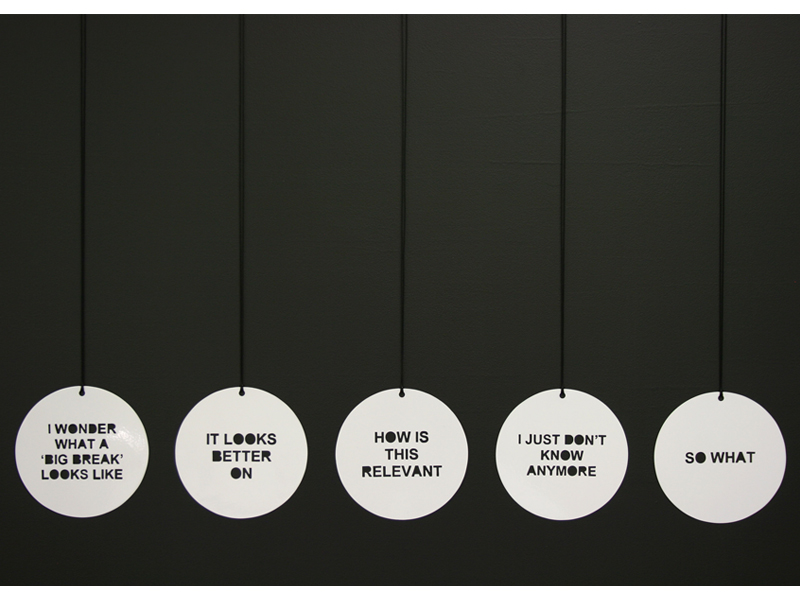

Your jewelry is about ideas. On a recent trip to Australia, I saw pieces from your series A Failure to Communicate, More or Less. They were large metal discs with phrases such as “It Looks Better On,” “I Don’t Want To Fall In Line,” “This Is Bigger Than You Are,” and “So What.” I was so intrigued! They captured what we think but may not express. Is that the point? To use jewelry as a communication vehicle?

Zoe Brand: Exactly. I’m interested in how we recognize and understand signs. Jewelry is a sign on the body; it can lead us to glean some information (rightly or wrongly) about the person who is or isn’t wearing it, and we can come to conclusions even before they have spoken a word. I take this approach to jewelry quite literally and use text in my work as a very direct means of communication, even if sometimes it’s a little ambiguous how a viewer might understand it. Contemporary jewelers have the unique problem of showing work in galleries without the body that it’s supposed to live on. I take advantage of this situation and pose questions about how the work is read and understood in a gallery context and conversely how it’s read and understood on a person. So What, for example, can be taken any number of ways. In a gallery the viewer might look at it and think dismissively “exactly, so what?” Another might laugh and think, “I would love to wear that at work,” or further still, a personal mantra, “so what if it’s all gone to the shit?” I like that we all have our own personal, cultural, and historical baggage that we bring when viewing an artwork that allows for open interpretation and consideration.

I was also amused by the pieces—they were witty and made me smile. What role does humor play in your jewelry? Do you find that it is a quality missing from this field? Would this have to do with jewelry wanting to be taken seriously?

Zoe Brand: I’m generally attracted to work that uses wit and humor to explore an idea. Firstly the work is funny, then after unpacking the ideas or the visual cues built into the artwork, I get to the cheeky, cutting, or cynical intent. Sometimes this is instantaneous, other times it’s a slow burn. For me it is also a means of entry into the work for the viewer, a lure to spend more time with a seemingly simple work and prod the audience to question why it is they have reacted that way.

Contemporary jewelry could probably do with a little more irreverence from the inside. Admittedly it is incredibly difficult to balance the trope of jewelry about jewelry for jewelers (or the idea of the contemporary jewelry field making self-referential work so that only an initiated audience gets the inside joke), and exploring an archetype of jewelry as a means to get to the punch line. Contemporary jewelry wants to be taken seriously, but I don’t think it’s because of its lack of humor. So much jewelry lacks real conceptual depth to be taken seriously in an art context. I think it was in Liesbeth den Besten’s book On Jewelry that she poses the question, “Maybe we just make bad art?” I really do think about this all the time. However, we are also so fortunate that our field traverses so many other disciplines such as fashion, craft, and design, and in these we certainly stand tall.

Your new work in the Bilk exhibition is about how we consume and understand signs, particularly signs in a commercial, retail environment. Jewelry, historically, has a strong relationship to consumerism, usually about making people feel special about themselves. Are you poking fun at this aspect of popular culture?

Zoe Brand: This new body of work is treading that fine line between jewelry about jewelry and a humorous and cutting look at how we consume not just jewelry but all desirable objects. The work explores and questions the motions and thoughts we go through when justifying a purchase. I’m using language that we find in sales catalogs and in advertising, and recontextualizing it to be about a person, not just the thing. Words like SPECIAL, REDUCED, QUALITY, GENUINE, WAS, NOW, ONLY. By making this the artwork as well as the selling point, I am poking fun at the machine in which we as consumers (and makers) are a component, but sometimes don’t want to or aren’t willing to acknowledge our part.

Thank you, and best of luck to you both.