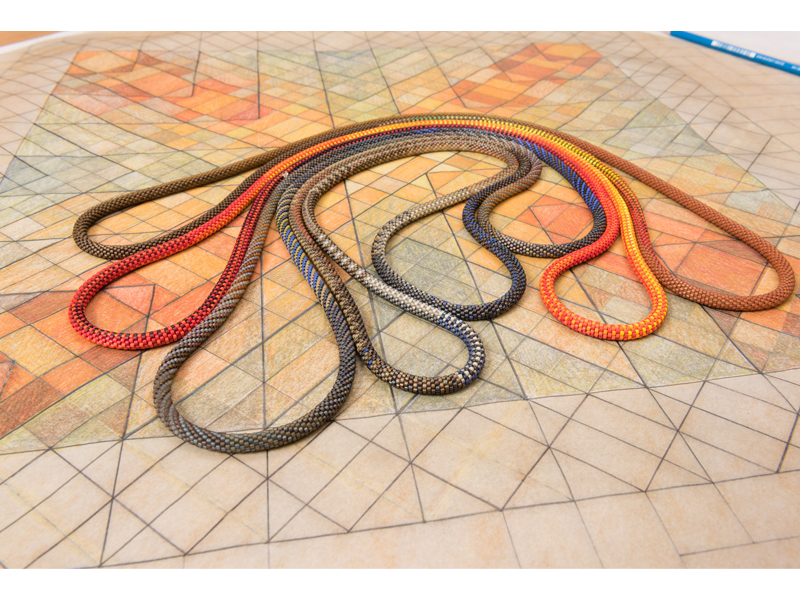

I’ve been familiar with Claire Kahn’s sensuous, snake-like ropes of bead crochet for some time, but have come, only now, to marvel at the true beauty and technical accomplishment of these necklaces and bracelets. A designer, maker, and artist, Claire is a true generalist among the arts, working across mediums and scale to create works that are connected by her fascination with pattern, texture, color, progressions, and transitions. Whether it’s a mixed-media art installation, a water fountain at the Bellagio, or a luxurious necklace, her works are complex mosaics inspired by nature and architecture. On the eve of the opening of her new exhibition at Patina Gallery, Peaceable Kingdom: Claire Kahn’s New Mexico, Claire talks about her background growing up in a family of accomplished artists, her multifaceted body of work, and her recent move from San Francisco to the Pojoaque Valley of Northern New Mexico.

Bonnie Levine: You have such a rich and diverse practice: jewelry maker, graphic and textile designer, mixed media artist, designer of large-scale water sculptures—do you consider yourself a maker, an artist, and/or a designer? Are those meaningful distinctions?

Claire Kahn: I’m a designer and maker, but some say a designer doesn’t actually make things. I disagree. As a designer, my work is informed by the materials and processes I use, so I am also a maker. I think to some the word “design” implies something that is designed and then produced in large numbers, even mass-produced. My pieces are one of a kind; their design, although sometimes similar, is never repeated, but I would still consider them as design. I’ve never been comfortable calling myself an artist. Somehow it sounds phony. In my experience, people who call themselves artists really aren’t. Other people can call other people artists.

Your parents are both artists. Tell us about them and what it was like growing up in a family of artists in the 50s and 60s. Did you ever want to do anything else?

Claire Kahn: My parents met as students at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, in the 40s, where the exploration of and emphasis on numerous mediums was an inherent part of the school’s philosophy and practice.

My father, Matt Kahn, was a designer and painter and professor of design at Stanford University (his was the longest appointment in the history of the university, from 1949 to 2012). He was beloved by thousands. He also had a prolific life as a painter. Unfortunately, the art scene, especially in the US, never liked the idea of a synthesis between art and design, so his career as a painter was obscure, but his work was brilliant. He loved and thrived on the uses of numerous materials and techniques and understood intimately many mediums. He was an accomplished metalsmith and taught metalsmithing at Stanford for many years. He also loved wood and fabric and designed textiles and taught textile design there as well. His syllabus for core design encouraged work and exploration in a wide range of media. I think I became a pattern maker largely because of his teaching. I was one of his students at Stanford.

I am influenced by my mother, Lyda Kahn, who was a weaver. Her mother, Anneke Vos-Van Thyn, was also a weaver and was a mentor to me. She was Dutch and a member of De Stijl, a movement established in Holland that coincided with the Bauhaus school in Germany. My work often looks just like my mother’s, her choices of pattern and color. I have a pattern in my beadwork called Lyda.

My folks would have supported any life choice my brother and I would have made, but creative work was the choice we both made (Ira is a fabulous photographer). Of course pursuing careers in design and art was nurtured and encouraged.

I can’t imagine a more blessed upbringing. We lived in a beautiful home designed by A. Quincy Jones for real estate developer Joe Eichler. My father was Eichler’s creative consultant for 10 years. He and my mother partnered to design all of Eichler’s model home interiors. We traveled every four years to Italy, where my father taught art and art history in Florence. We searched for local design and craft and explored the lives of artisans and cultures around the world, from Cambodia, in the 50s, to Europe and Mexico. My parents were collectors and had a deep love of ethnographic art. Holidays were celebrated with a kind of visual joy I can hardly describe. Really, the whole experience of life in my family was wondrous, from milestone occasions down to routine details: the way we wrapped gifts, decorated eggs at Easter, carved pumpkins for Halloween, or set the dinner table.

From an early age, you were exposed to—and currently work across—different mediums in your own practice. Is there an advantage to being a generalist rather than a specialist? Is this unique to you, or is it becoming more common in the art/design world today?

Claire Kahn: Specialty is fine, but only after the development of a broader knowledge of design. I don’t think a designer can be effective when working in a vacuum, blind to alternative disciplines, treatments, and media. I bring my understanding of color, pattern, even graphic design to all my work, whether in bead crochet or water feature design. Technology, the antithesis of material exploration, is now ubiquitous, and while it seems to allow for more choices, it inhibits, in my view, thoughtful exploration.

You came to making jewelry later in your career. What was the impetus for moving from large-scale works like water sculptures and art installations to very small-scale creations like necklaces and bracelets?

Claire Kahn: I never meant to have a career in fountain/water design. That happened as a result of developing graphic design and branding for WET Design, a water feature design firm in Los Angeles. The founder, Mark Fuller, was interested in bringing fresh and unique ideas to his projects, so he invited me and others—people who worked in design disciplines unrelated to water—to develop water features. Through the invention of new technologies in water and light, and with the support of individuals with abilities in numerous fields, WET Design created unique installations worldwide, the scale and design of which had never been seen before.

I came to beadwork because my mother had a collection of bead crochet necklaces in vibrant colors that were made in Greece. She wore them every day. I loved them and wanted to learn how to make them. I took a class at a local bead shop thinking bead crochet would be a hobby, but it developed and five years after the class, my work was finally good enough to present to Patina Gallery, which I knew and admired. The owners, Allison and Ivan Barnett, were the litmus test for the work. If I could show it there, I had reached my goal in its craft and refinement.

Your jewelry, paper cuts, water sculptures, and textile designs are all characterized by intricate patterns, rich textures, and technical progressions. Please tell us about these defining aspects of your work.

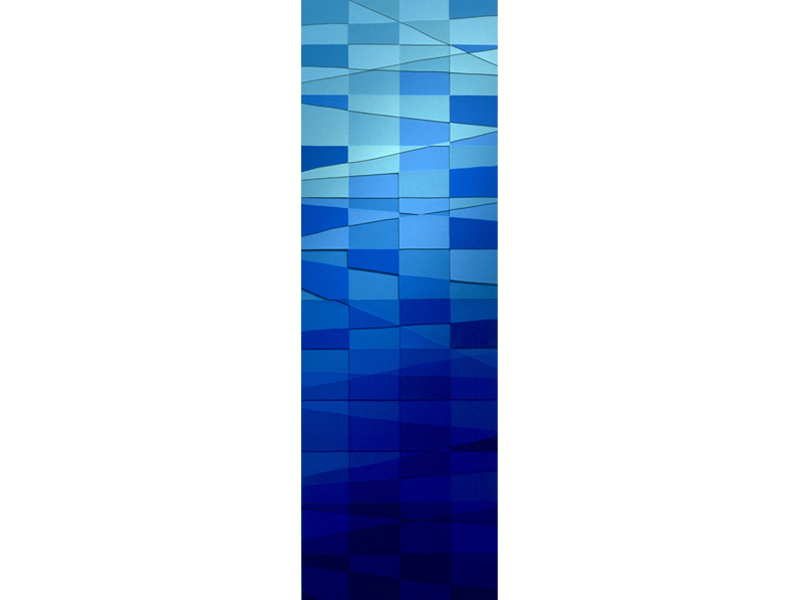

Claire Kahn: My first job was at the San Francisco office of the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). There, I was able to explore my interest in pattern through the development of building exteriors, paving pattern, interior design of custom textiles and carpet, and architectural graphic treatments. I think I started to see design there as a kind of mosaic, where numerous smaller units could come together to create a whole work that would progress and change in color over a larger span, a wall, or ground plane (work at SOM was always in an environmental context). I then was able to extend this interest to my own work in paper and paint, and then in water when I went to work in water feature design. The LA Music Center fountain, the Fountains of Bellagio, and others were installations made of hundreds/thousands of units, jets of water, and light, combined to create a larger, singular, kinetic water expression. Water, white light, kinetics, and water choreography replaced color as a way to create progression and transition in a water feature design.

In my bracelets and necklaces, tiny beads combine to create pattern and progression. My necklaces are at least 110 mm long and now have no break or clasp, so the progressions are continuous. Color and pattern can morph as the piece’s linear pattern evolves. The animation comes from the wearer’s movement and the way light interacts with the gems that embellish a piece.

Your upcoming exhibition at Patina Gallery is called Peaceable Kingdom: Claire Kahn’s New Mexico. What is “peaceable kingdom” a reference to, and how is it explored in the work you created for the show?

Claire Kahn: Ivan Barnett, co-owner of Patina Gallery, thought of the name. I have told Ivan about the new unknowns I find here in the Pojoaque Valley, different from urban life in San Francisco, and I often comment about all the amazing animals that live here. I have a pond that attracts beautiful birds, and the barrancas (cliffs) nearby are home to coyotes, bobcats, bear, and bison. The pasture beyond my house is home to three beloved horses. I also have been talking about how peaceful it is here and how the serenity here has inspired my work. Ivan remembered a series of works by Edward Hicks called Peaceable Kingdom, paintings that show a collection of animals in soft light among landscape elements in a lovely, tranquil, and quiet atmosphere.

Some inspiration comes from the color and light here. There are pieces that show autumn, unlike the quiet muted colors of my home in the SF Bay Area. Here the fall colors are vibrant, whether they are found in the stands of aspen trees in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, or during walks I take with my neighbor Mary through the nearby arroyos and barrancas. There’s also a condition of light here that my father referred to in his lectures. It’s rare everywhere else, but seems to be common here in the summer monsoon season, where the sky is slate gray and everything in front is vibrantly lit. Greens, yellows, whites are in stark contrast to the dark backdrop of stormy sky and clouds.

I love the very rich, saturated colors in your work. Where does this inspiration come from?

Claire Kahn: The 1.5-mm beads I use allow for interesting mixes. As in textile design and my mother’s weaving, I can create a rich neutral mosaic by mixing vibrant opposites, so some of my work will combine complementary opposites like red and green, or yellow and purple. At any distance, the eye mixes these colors, resulting in a much richer neutral than if I were to simply use a monochromatic gray. I also use combinations in a given color group: warm, cool, bright, and dull blues mix beautifully, for example. I love quiet color, too, and it supports more vibrantly colored gemstones. The colors of the gems I use—sapphire, tourmaline, and diamond—determine the colors that will go with them in the bead crochet rope. I will often build a piece around beautiful gemstones.

Can you explain your technique in creating these pieces? Do you start with a mathematical model, or does the design evolve as you work? Do you use technology to create and design the patterns, progressions, and transitions?

Claire Kahn: The crochet technique has to be scripted. Pattern and progression are determined by the stringing of beads on the thread that is crocheted in a spiral loop to create a piece, so it’s all predetermined before I start. I compare it to ikat weaving, a technique where the pattern is determined in the yarn before it is woven into a textile. Each yarn is dyed in precise places along the strand that, when combined in a woven fabric, reveal the design. Only as the textile is woven, or a necklace is crocheted, does the design emerge. This is unlike anything else I do, where I can change the painting or paper cut to evolve and can develop a piece as I make it.

I cannot sketch the work or use a computer program to predetermine how it will look when finished. The closest I come to sketching an idea is to actually crochet a length, but even that is unpredictable as I find a piece looks very different from 50 to 200 mm, or even 500 mm. So it’s a bit of a guess from start to finish as to whether a piece will be successful. I don’t have a mathematical formula that I follow, and I don’t prefer patterns that require memorization, but I do often notice a kind of mathematical elegance and logic in a pattern that was never intended.

Your jewelry is very evocative of ropes of snakeskin—very tactile, sensuous, and beautiful. Is there a particular significance to the snake as a metaphor or motif in your work?

Claire Kahn: The snakeskin part was an accident and just happens to be the way pieces often look. I sometimes will be inspired by a snake and will create a piece that emphasizes that quality, whether it’s the lighter underbelly, or a subtle geometric pattern. Early on I was making pieces that were more literally snake-like, but I soon got that out of my system. Snakes are beautiful enough just as they are, and my beadwork will never come close to being as beautiful as the real thing. I don’t like derivation or copying. I prefer to interpret a subject and really make it as much my own as possible.

I appreciate your comment on the piece’s tactile and sensuous quality. My father used to say, “Design is the art form that is incomplete until it is engaged.” The bead crochet technique provides gifts, and one of them is how tactile and supple the ropes are. They are very strong, but soft to the touch and very comfortable and wearable.

You’ve recently made a major move from the San Francisco Bay Area to Northern New Mexico. What was the impetus for the move, and how might it influence your work going forward?

Claire Kahn: San Francisco was my home from 1977 until now, and I was born in Palo Alto. I will always love it there. I recently inherited family treasures that I didn’t want to store, and San Francisco has become so expensive that it’s hard to afford the space needed to have everything at home. I found a beautiful home here, designed by local architect Mary Reeves. It’s modern, open, and uses sensuous and beautifully varied materials. I think it’s like a quilt of steel, stone, wood, and glass. The house is beautifully sited on a pond with pastureland and the Jemez Mountains in the distance.

My work has been structured in response to urban inspiration and historical treatments by others: “the hand of man.” I mentioned Lyda, a pattern inspired by my mother’s weaving. There’s also Mughal, inspired by antique, royal jewelry of Northern India; Batlló, kindled by the work of Spanish architect Antonio Gaudí; Folon, based on the color progressions of Belgian painter Jean-Michel Folon. But now I am looking at new pattern, or un-pattern ideas. I’m living in a less ordered and less predictable, softer place. This environment requires me to look at patterns that seem random and organic, even though they aren’t, can’t be. It’s the nature of the crochet process to work in a grid, but within that system I want to create work that is more implicit, mysterious, and visually unpredictable. It’s a delightful challenge.

Patina Gallery is here in Santa Fe, and having a studio near the gallery, where clients can visit, is a great opportunity.

What other projects are you currently working on, and what have you seen or read recently that you found inspiring?

Claire Kahn: There are aspects of bead crochet that, because of its scale, don’t read clearly. I would like to create a series of works on paper that show the hidden patterns in a larger scale, not diagrams or duplications of the bead crochet pieces, but drawings in pencil and ink that are more like responses to the crochet. I would also like to create a series of works on paper that would pair well with the bead crochet work for a future show.

I am enamored with the exquisite way Allison Barnett curates and stages the collections of jewelry and fine art at Patina Gallery. I feel privileged to keep company with the incredible artists who show their work there, and to have my work among theirs is profoundly motivating. I want to continue to think about the gallery’s collections and how my work, whether bead crochet or other, engages the gallery’s aesthetic.

Thank you.

The work in the exhibition ranges in price from $780 to $13,000.

INDEX IMAGE: Claire Kahn, Progression, White, Blue, Black, 2016, necklace, cylindrical glass beads, 1,143 mm long, 6.4 mm diameter, photo: Dianne Stromberg