Today, demonstrations to make a public statement about any social, political or environmental issue often become flamboyant events. Crowds flock the streets. They dress up for the occasion wearing clothes, hats, flags, and handwritten protest signs that express their grievance, ideals, or aims.

Since texts appear to be more powerful than signs, political buttons have become obsolete. Who needs a small sign on the body when a big text, or all of your apparel, can be a sign of your intentions?

Political buttons were very popular from the 1960s to the 1980s. They were one of the last utterances of a once well-understood function of jewelry: to be a sign not only of power but also a state of being, or of belonging to a certain community. In 1978, Paul Derrez organized an exhibition about political buttons in his fresh, new Gallery RA. Together with some friends of the gallery, Adri Hattink (1947–1998, a Dutch jewelry artist and sculptor) and Julia Manheim (a well-known British jeweler in the 1970 and 80s), Derrez started to actively collect political buttons. He even published advertisements to ask people for their help and input in organizing this exhibition. The gallery had a machine with which people could make their own buttons. The Dutch jewelry scene was rather stuck in formalism at that time. By emphasizing the social and political meaning of buttons as jewelry-like items worn on the body, Derrez hoped his activities would stimulate jewelry makers to widen their practices.

The social meaning and function of jewelry still exists, of course. It’s expressed most clearly in the wedding ring, for example. But jewelry’s function of making a statement that goes beyond beauty, wealth, or taste has become less obvious today.

For Derrez, the social meaning or social relevance of jewelry has always played a role in his life and work. This may perhaps not be present in each piece of jewelry he creates, but is still a recurrent theme.

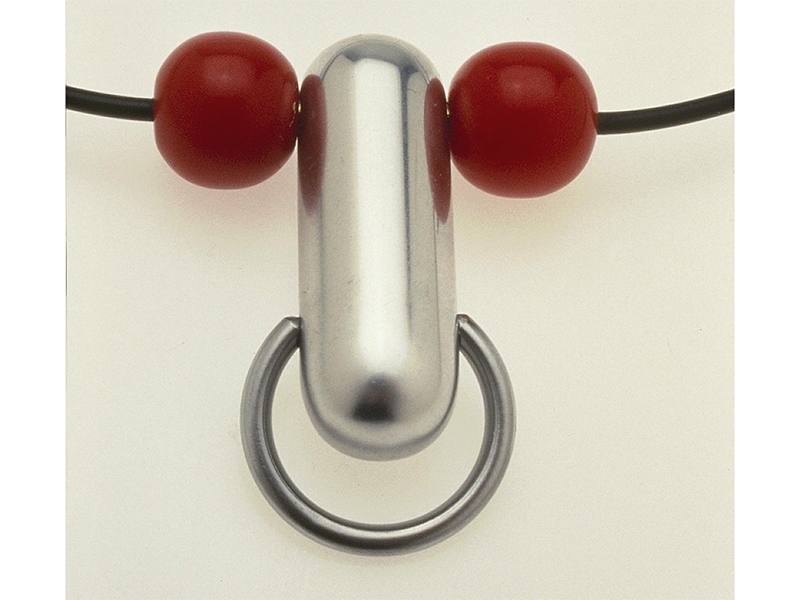

Just think about his Pill Roulette brooches (2003). They comment on the excessive use of medicine and party drugs. The triumphant silver and acrylic Condom–Monstrance (2005) is a remonstrance against the Catholic Church’s birth control policy and ban on the use of condoms. (The Museum Het Catherijneconvent in Utrecht, a museum for religious art, acquired the monstrance.)

From 1995 to 1996 Derrez designed various jewelry pieces as a cry from the heart about losing so many friends to AIDS in the period 1983–1996. The Bleeding Heart and Cry-Cry pendants (1996 and 1995), and the memorial chain Love Hurts—Dare to Love (1996), with 24 fluorescent pink acrylic hearts inscribed with the names of friends of Paul and his husband, Willem Hoogstede, who died of AIDS, are examples of this. (Love Hurts—Dare to Love recently became part of the Rijksmuseum Collection.)

In 1994, Derrez received a request to design men’s jewelry for a fashion show in Amsterdam. That year and the next, he delved into real man’s stuff found in gay subcultures and sex shops. The resulting Risky Business collection expressed his self-awareness as a gay man. The aluminum, rubber, and acrylic pendants presented a range of variations on the phallus. They were a blend of adult toys, crosses, and faces. Part of this collection of men’s jewelry was a series of brightly colored acrylic knuckle-duster rings adorned with positive slogans such as Dare to Love and Ring My Bell. Derrez had come out in 1969, but this collection announced his arrival as a gay jewelry designer.

A three-sided aluminum dagger, In Gods Name (2003), showed his rejection of religion. Each side of the dagger is engraved with a symbol of the three major world religions. It gave him great pleasure to find out later that the nice, well-groomed lady who bought the dagger from his gallery used it in her counselling sessions with clients to open up the conversation. “This is exactly what I like,” says Derrez, “that my work leads to discussion.”

Liesbeth den Besten: Paul, tell me where the Pride Power project comes from, and what exactly it entails.

Paul Derrez: I have always been personally interested in subcultures, street styles, dressing up, and drag queens. Willem and I like to go to bars with drag performances. So one day we decided that we wanted to organize an exhibition about drag. We presented a proposal to the CODA Museum. It was accepted. Even better, the museum added a curator to the exhibition, Roosmarij Deenik. The three of us, Willem, Roosmarij, and I, did the research. We were a great team. Roosmarij was crucial as a researcher.

We did a lot of fieldwork and many interviews with drag queens, fascinated by their personalities and stories. It resulted in the exhibition Drag Power—Gender, Pride & Glamour (at the CODA Museum November 2019–March 2020), which included the history of drag. The exhibition was arranged around five different characters, four drag queens and one drag king. The story of their lives was captured in extensive interviews on videos. You can say that it showed the power of resistance, which you need when you want to change things. The title Drag Power was important. This exhibition was not about marveling at strange types, but rather about positioning them as lifestyle champions. The word power turned out to be crucial.

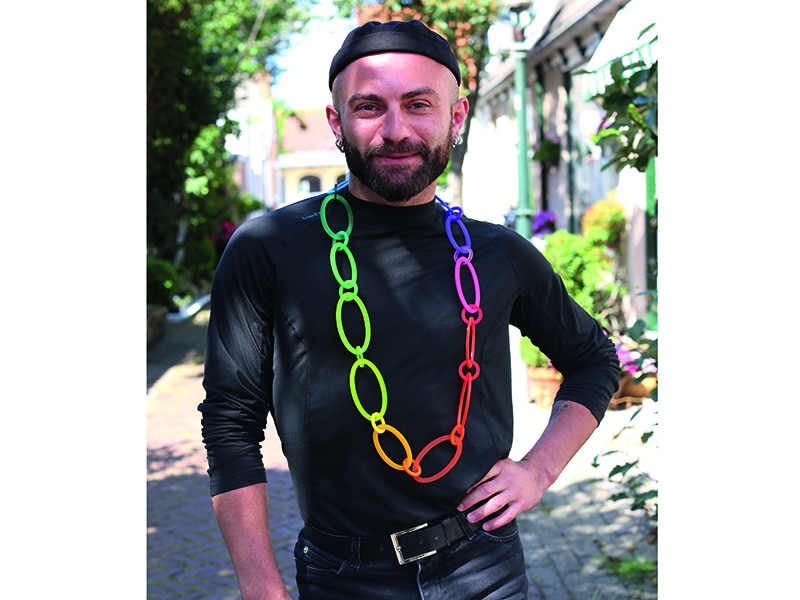

I had already been working on an acrylic rainbow chain for about five years. It was quite a project, not easy. Like I always do, I started by making the design by hand. I made a few but it was a lot of work, especially the polishing. And it was too expensive. I consider those first handmade chains as prototypes. After you’ve made three, it then becomes another thing. The advantage of working this way is that you get new insights—technically, materially, and in terms of design and calculation—while making. Two new chain designs were added to the initial design.

I wanted to make an edition of Rainbow Chains for the 25th anniversary of Amsterdam Pride, in 2021. It needed to be a positive statement for people to show who they are, and to show your solidarity with the fight against homophobia. The fear of, and aggression against, gays is increasing all over the world, even in the Netherlands. I couldn’t have imagined this in 1969. Once I knew exactly what I wanted, I went to the Perspex company I often work with. I wanted to use more colors than in the handmade chains but was afraid that 25 would be too complicated. No problem, the colors were available. And the company could easily translate my working drawing into a computer program. Based on the amount of material the company has, I can produce about 10 chains of each of the three models.

Twenty-five colors are much more than the number in the rainbow banner. In 1978, the American activist Gilbert Baker designed the first rainbow flag in eight colors. Since then, colors have been removed or added. Each color has a symbolic meaning. And the rainbow symbol is becoming more complex and debatable. I took the liberty of using many more colors because I see the rainbow as part of an emancipatory process. For me, these 25 colors express the idea that gender and identity are in flux, that there are many transitions and differences between people. So, 25 colors also serves as a symbol.

Why did you choose the link chain?

Paul Derrez: A chain is a piece of jewelry traditionally worn by men and women equally. A fine chain (with a pendant) is an object generally recognized as an object of love. I think it’s great that by wearing something you can make a social, cultural, and political statement. Of course, this is also possible with wooden or plastic beads. But the link is itself a symbol for connection … although I am aware that a chain can also mean the opposite: oppression, deprivation of liberty, slavery.

By making something more beautiful, you lift it. It then goes beyond being a mere symbol. The Rainbow Chain is wearable and decorative on the one hand, and a statement of solidarity and respect for the LGBTQIA2S community on the other. Through its colorfulness it expresses joy and pride. It’s a positive statement that appeals to many people, and is necessary in these times. I have just returned from the Grassi Messe, a fair in Leipzig, where I had a booth. I had a beautiful encounter with a mother who bought a chain, with enthusiastic encouragement from her two daughters. Earlier I received an order for two Rainbow Chains from a woman in New Zealand. She bought it for her daughter and her girlfriend, who are about to get married.

You also produced a publication, illustrated with many beautiful portraits of people—gay and straight, young and old, black and white—photographed in the streets of Amsterdam, Haarlem, and Zandvoort. Why did you publish it?

Paul Derrez: I have always liked projects with a certain theme, doing research, inviting artists to participate, making an exhibition and a publication. Over the years I have made eight publications, but they were all gallery- and art-related. Anyway, I like the format, and I have a wonderful team. Nel Punt does the graphic design. Roelien Plaatsman translates. MisjaB takes the photos.

For Pride Power, I wanted to make an informative and readable publication about the struggle of gays to be themselves, historically and today. This publication isn’t about contemporary jewelry or art jewelry. It seeks a wider audience. I’m glad it’s now in general bookstores, where people can find it and buy it with a special reason for someone.

Some people will know I’ve photographed my jewelry worn by people on the street before. The first project, called Street Scenes, was made for my publication Paul Derrez, Cool Creator (1997). On this occasion, photographer Ton Werkhoven and I asked passersby to wear a piece of my jewelry. In hindsight I think at that time I used people as some sort of pedestal. There was hardly a connection between the person and the jewelry s/he was wearing.

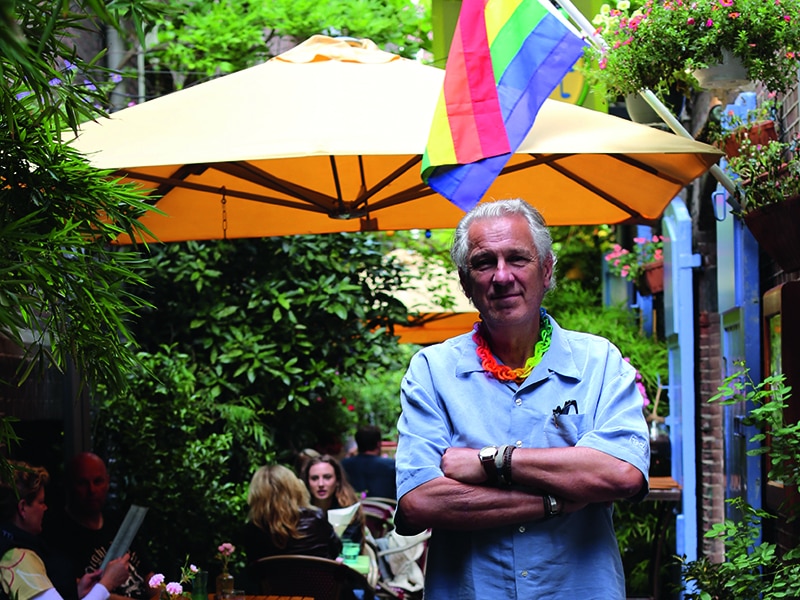

The Pride Power project was totally different. I collaborated with photographer MisjaB, with whom I have worked before in a very pleasant way. Street photography is her specialty. As a kind of test we started by asking people in a familiar environment—on the Grimburgwal, in Amsterdam—whether they would like to wear a rainbow chain for a photo. All the reactions were positive. Instantly, it was clear that people understood what it was about. This is about connection, and you can see the pride connected with rainbow activism on the faces of the people in the photos.

Then we took photos this summer at Pride on the Beach, in Zandvoort, and Pride Walk, in Amsterdam. The people who participated were not only gay people. A lot more people participated. They loved it! This is a project about solidarity. Thank God, this is possible in the Netherlands, where there is a lot of support.

People radiate pride and fun, that’s what really struck me. Tamaz, a Georgian activist from Tblisi, and one of the people behind Tblisi Pride, was in the Netherlands because of Pride. In the photo he looks relaxed and at ease in his long Rainbow Chain. But his situation in Georgia is the opposite. In his country, gay people are outlawed and suffer tremendously under state-sanctioned violence.

Of course, you won’t change the world with Rainbow Chains, but sometimes you just gotta do things.

Read more about the history of worldwide gay activism in Rainbow Chains. That publication and Pride Power are for sale via The Pool (Amsterdam), Galerie Biro (Munich), and Paul Derrez (mail@galerie-ra.nl). The books are also available via Chrome Yellow Books.

All proceeds for the Pride Power Project will go to COC Netherlands. Since 1946, COC has advocated for the rights of lesbian women, gay men, bisexuals, and transgender people. COC has a special consultative status with the United Nations.

The CODA Museum acquired all three models of the Rainbow Chain; the Grassi Museum, in Leipzig, Germany, acquired the medium-size Rainbow Chain.