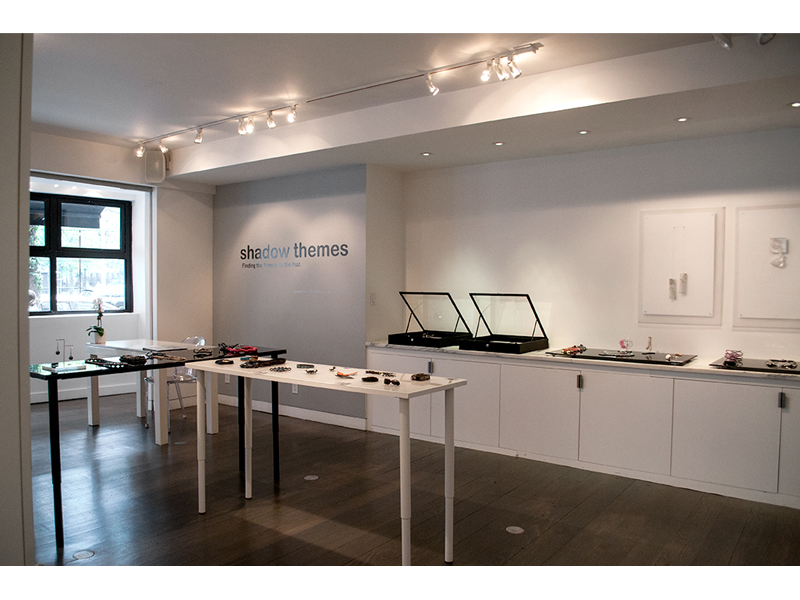

Shadow Themes, the brainchild of writer and educator Marjorie Simon and jewelry artist Biba Schutz, is a group exhibition at Reinstein|Ross that peers into the intuitive minds and fluid studio practices of 33 metalsmiths. In this interview, I talk to Marjorie and Biba about their curatorial collaboration and finding inspiration in the art of William Kentridge, a South African artist who often experiments with the malleability of time.

Olivia Shih: Hello, Marjorie and Biba! The two of you have been friends and colleagues for over a decade, but this is your first joint curatorial venture. How did the pieces fall into place for this exhibition?

Marjorie Simon and Biba Schutz: We have been friends and colleagues for at least 15 years. Our relationship is built on friendship, mutual respect, professionalism, and time spent together. Our discussions of work and process have always been informative, and even when we don’t agree we learn from and appreciate each other. Our practices and skill sets complement each other, but our common interest in the field always brings us together. Within the last five years we had been talking about doing a collaborative project. Eventually, co-curating a themed exhibition felt exactly right. We are always excited to share a William Kentridge experience, whether performance or installation. When the opportunity arose to present a project to Reinstein|Ross, we thought of his practice and its relation to the values we share as artists.

The title of this exhibition, Shadow Themes: Finding the Present in the Past, suggests that artists gain insight by reexamining metaphorical skeletons and literal previous bodies of work. How were artists invited to dig through their pasts?

Marjorie Simon: The title comes out of my own experience of understanding the origins of my work. I’ve often said that I don’t consciously address life themes in my work, but when I look at the work, I know where I’ve been. I universalized this observation in the title—one person said, “It’s what we do.”

Biba Schutz: I wanted to curate a show that would be personal to my own studio practice. We asked artists to find a thread through their work and show how current work was related to earlier work. One way might be to literally return to an early work or body of work and reinterpret it. It might be an unfinished piece that just wasn’t ready to be “born.”

You’ve told me that South African artist William Kentridge views “the world as process, not as fact,” and his perspective helped you define the core of your exhibition. Could you delve deeper into why his work relates to Shadow Themes?

Marjorie Simon and Biba Schutz: We both admire Kentridge’s work, seeking it out and delighting in finding it serendipitously. We continue to be inspired by his material explorations and the way he verbally articulates his process. The charcoal animations make process visible. The way he talks about the meaning of themes in his work resonates with us as makers—the personal, the political, the way he used his own body in the animations, the way he confronted apartheid and personalized it by using his own body as a model, the torn paper animations of Shadow Procession (1999), with its echoes of the Holocaust—his voracious appetite for process. Whether in film, theater, drawing animation installation, artist books, process is paramount. Though he would never consider himself a craft artist, we respond almost viscerally to his materiality.

Your invitation to the 33 artists is anchored on the idea of iteration: revisiting past themes, discarded works, unfinished ideas in order to reactivate them in the present. This plays into metalsmiths’ propensity for self-reflection, but also solidifies the myth of the lone maker having a conversation with him- or herself. Could there be a risk there?

Marjorie Simon and Biba Schutz: We don’t see a risk. We have simply identified the way artists already work. We are fortunate to reinterpret and delve into our own memories, but we do not see metalsmiths as having more of a “propensity for self-reflection” than other artists. All artists—poets, composers, painters, choreographers—have conversations with themselves. It doesn’t mean they subscribe to the myth of the lone genius, in the way that description held sway during the era of Modernism. For one thing, there is a lot of conversation about our shared heritage, our metalsmithing forebears. Another issue is the craft tradition of making and materiality. We constantly balance the tradition of handwork and innovation with not repeating oneself or plagiarizing the work of those who came before us.

Intuition and a fluid making process are vital to the theme of this exhibition, but do you think it’s possible for an artist to rely too heavily on intuition? Does a fluid making process conflict with a more structured, conceptualized approach to art jewelry, or can the two coexist?

Biba Schutz: As a maker who starts intuitively and conceptually, I really don’t see the conflict. Making a wearable object immediately references function, and for me creating function uses the concept of structure. I don’t think this needs to compromise the work; often it enhances the sensuality of the object with the sexuality of the body.

Marjorie Simon: Certainly artists can rely on intuition to the detriment of good design. But intuition can also be a part of a very structured approach, for example in the work of Simon Cottrell. I would have to say that the best work probably must be conceptual as well as intuitive.

I’ve noticed that even though the 33 artists in this exhibition are diverse in experience, age, and race, they are all North American women. Was this a conscious decision?

Marjorie Simon and Biba Schutz: Yes and no. As we were putting together our wish list, balancing it for generational representation, we realized we had chosen mostly women. We simply decided to make it a show of women artists. We are proud of the many women in American metalsmithing, and we honor that tradition. We believe that Americans are under-represented globally and we wanted to offer a corrective. Even though it is a large show, there are many more noteworthy American jewelers who could have been included.

Marjorie, with your BA and MA in sociology, how has the field and academia influenced your artwork, writing, and curatorial practice?

Marjorie Simon: My academic background has influenced my writing much more than my studio practice. When I first started writing professionally, I felt I had a lot of catching up to do because of my lack of art school experience, especially in the vocabulary of criticism. But now I am grateful to my social science training because of its breadth. I was trained to see many threads in a culture at the same time. I now feel that broader vision is an asset in research and writing, that I make use of sources from a greater range, and I am more aware of context. In writing about individual artists, I always want to know their stories, how someone gets to be the person I’m writing about.

Biba, you trained as a printmaker and graphic designer before evolving into a full-fledged jewelry maker and metalsmith. How do “shadow themes” figure into your studio process and work?

Biba Schutz: I am always aware of where I have been. Studying as a graphic designer honed my eye and my problem solving. Designing type taught me about the relationship of space and form, and working in the field helped me to develop the skills that are daily evident in my studio practice. I was fortunate to have a mentor who pushed boundaries and took bold risks. Along with my father, he introduced the idea of following your passion. The magic and mystery of printmaking give me the patience for my exploration of materials and processes.

Your exhibition, Shadow Themes, includes a meticulously assembled catalog of each artist’s previous work, new work based on previous work, and artist statements. Why do you think documentation is so crucial?

Marjorie Simon and Biba Schutz: We each feel it is crucial to document work. Biba understands the power of the image. Marjorie is very much a print person. It is our shared history, even out here on the margins of the decorative arts. We both have a strong desire to record not only the objects, but also how they came into being, better to understand their place in history. We acknowledge what we have learned from those who came before us, and are conscious of passing that knowledge to generations who will follow us. We both recognize the power of the object—the book—as tangible evidence of our existence.

You’ll be hosting a talk with several of the artists. Is this a way to extend the conversation in the minds of the public? What do you think are the biggest challenges, today, for ensuring an exhibition’s legacy?

Marjorie Simon and Biba Schutz: Because New York is a magnet destination, an unusually large number of participating artists were planning to attend the opening. An artist talk is a way to capitalize on this rare opportunity for the 13 jewelers to be together, as well as for the public—students and collectors—to have access to this creative group. At the time of writing this, the conversation hasn’t happened yet, but it is our intention for the gathering to provide a way for others to participate in the artists’ process.

The challenges for the legacy of a gallery exhibition are great. The intimacy of a gallery, which can make for a richly immediate viewing experience, cannot compete with a museum exhibition. If the show doesn’t travel, it is likely to be limited in space, duration, scope, budget, geography, audience, and thus impact. We certainly hope that our choices—a gallery of integrity, a print catalog, and a discussion open to the public in an accessible location—will help create a footprint. Reviews and social media become crucial partners for disseminating information. Ultimately, the show’s legacy will be the artists continuing to make great work.

As makers and curators, you must always be on the lookout for thought-provoking art, podcasts, and books. Would you share a few recent favorites with us?

Biba Schutz: Living in NYC, I get to see the most amazing theater and art. I am drawn to repertory, dramas (classics), intimate small audience, multi-media, experimental, as well as on and off Broadway. I was just delightfully surprised this week by the Bedlam Company’s performance of Sense and Sensibility. This spring brought Gerhard Richter and Richard Serra to NYC. This fall brings Georg Baselitz and Sally Mann. I love to travel, but that means I miss out on my NYC life.

Marjorie Simon: I rely on travel, and the serendipity of discovery. I haven’t missed the Venice Biennale in the last 10 years. Anything by William Kentridge, of course, most recently, his staging of Alban Berg’s opera, Lulu. By chance I recently saw a devastating political installation and videos by Vietnamese artist Dinh Q. Lê, Memory for Tomorrow, at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. Books: Dipping into John Berger. Eileen Myles, The Importance of Being Iceland. Wilhelm Lindemann, ed., Thinking Jewellery: On the Way towards a Theory of Jewellery.

Thank you.

The works in this exhibition range from US$300 to $15,000.