Lauren Kalman, a visual artist and educator based in Detroit, is celebrated for her innovative work, which lies at the juncture of art jewelry and performance art. Her work dissects and reassembles themes such as beauty, adornment, and body image, while simultaneously challenging the boundaries of art jewelry. With Kalman’s vision, it’s no wonder she’s one of the finalists for the Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant!

Olivia Shih: Although your education in the arts began with a BFA in metals, your work has evolved from art jewelry to encompass photography, video, and performance. Do you still consider your work to be art jewelry?

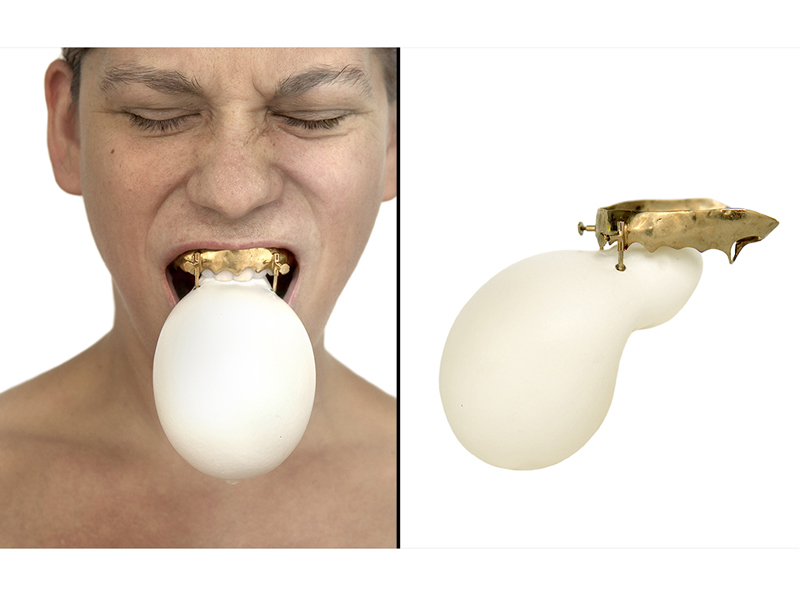

Lauren Kalman: I do consider my work to be art jewelry. I also consider it to be sculpture, photography, video, and installation. Early in my career, I made a move from jewelry as the form of my work to jewelry and adornment as the subject of my work. This opened up my practice to include other media while still being about or related to jewelry. My approach, sensibilities, and the social and cultural contexts of my work are rooted in the crafts at large and jewelry specifically. Almost all of my projects involve building wearable devices, and often these utilize metalsmithing techniques commonly found in jewelry.

Architect Adolf Loos propelled modernism forward when he shared his moralizing views on adornment as crime, but adornment is front and center in your work. What are your thoughts on his essay?

Lauren Kalman: I used Loos’s essay as a jumping-off point for the body of work named But if the Crime Is Beautiful…

It responds to his 1910 lecture Ornament and Crime, where he proposes that ornament is regressive and primitive, and that in (his) contemporary society, only criminals and degenerates are decorated—and this includes women. Loos’s writings on architecture and functional art helped to define the principles of the modern architecture and design movements. The influence of these movements permeates the contemporary built environment and therefore impacts our psychological and bodily relationship to space and objects.

Though Loos’s philosophies have been critiqued for decades, we continue to live in environments where Modernist constructions remain, and Modernist design objects have morphed into coveted icons of status, aligning the owner with the taste level of an educated or elite class.

The iconic furniture in But if the Crime Is Beautiful… represents this Modernist lineage. In this installation, the decorative metal, beading, and garments contrast with the male-dominated Modernist aesthetic and its utopian values of minimalism and functionality. White, in this work, is a symbol of restraint and intellectual control, a color historically used by oppressive entities, including the Fascists, as a symbol of superiority, purity, and control.

In recent history, craft has been recognized as a medium that endures outside of the white, male-dominated, contemporary art/design world. Crafts have been socially constructed to be associated with the domestic, collective, and female. As my work deals largely with the female body, it calls upon historical associations with craft and the feminine. My recent work has utilized a sterile aesthetic combined with crafted objects, adornment, and the female body in ways that are often grotesque or uncomfortable, to question an art historic narrative that privileges a utopic and myopic male, Eurocentric narrative.

In the recent Museum of Arts and Design exhibition that you just mentioned, But if the Crime Is Beautiful…, you tackle the subject of gold—plastering rooms, vitrines, and images of the human body with golden kudzu leaves. The invasive plant species multiplies throughout the museum exhibition, threatening to engulf the willing viewer in a shimmering frenzy. Why do you think humans are so enamored with gold?

Lauren Kalman: Gold has been a symbol of wealth and power because it has signified purity, immortality, and permanence in many of the world’s cultures since it does not tarnish or degrade over time. It also has associations with magic and celestial bodies. And then there is momentum; because of these ancient associations gold has continued to be used and reused symbolically.

Your project proposal for the Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant, Flourish, will explore gestures of attraction and repulsion, in relation to three subjects: wealth, decoration, and taste. Could you talk about what draws you to these three subjects?

Lauren Kalman: I am interested in the many connotations of jewelry. One of those is the connection to wealth through the display of precious materials and expensive labor on the body. I think taste is also connected to this. Style and materials can conjure constructions of “high” and “low” class, and the acceptance or rejection of historic material language can align the wearer with, or in opposition to, mainstream constructions of taste, value, and power. I often use gold and pearls as part of a material vocabulary that is associated with wealth and a particular kind of taste stemming from Western value structures. These are some of the problematic symbols of jewelry for me, and therefore it is interesting territory to explore. In Flourish, as in much of my work, I try to use jewelry vocabularies and materials in formats that unsettle or subvert.

Could you tell our readers a little more about your proposed project, including your decision to use historic dies from a 19th-century German jewelry factory to create parts for the project?

Lauren Kalman: Flourish is a new body of work that uses stampings from historic costume jewelry dies. In the summer of 2016, I was invited to work at the Jacob Bengel Foundation in Idar-Oberstein, Germany, a former jewelry factory established in 1873. There, I used historic dies and stamping presses to produce approximately 700 components. These pieces are all decorative elements that were used in costume jewelry. They will be used to make larger sculptural forms that interact with the body. I am particularly interested in the vernacular language the historic constume jewelry elements. Again, I think my interest is in the form’s association with taste and class (combined with the material associations I mentioned above).

In many of the images and videos you create, art jewelry and performance art are intimately built into one another. Why do you choose to work at the juncture between these two fields?

Lauren Kalman: I began using photography and video relatively early in my career. I was doing performance actions using gold leaf. These actions were temporal, so my use of photography and video started out as documentation. As I progressed, I began to think more about photographic theory, particularly photography and the imaged body. My work evolved to conceive of the photographs and videos as part of the work, rather than documentation of work. It forced me to think about what it means to use my body (the body in the vast majority of my work) or the body of a model in the images, given that clothing (or lack of it), visibility of the face, gender, and race all are part of the content of the work. Bodies are not a neutral ground for jewelry. This is why I choose, almost always, to be the model in my work. I feel it most appropriate to speak from my unique vantage point, as one perspective (rather than some universal truth) in a sea of identities and values.

Your exhibition, But if the Crime Is Beautiful, takes form in multiple variations, including one subtitled Composition with Ornament and Object. Here, the female body is adorned and mutated with gold, pearls, and iconic modern furniture. Could you talk about the role of gender in your work?

Lauren Kalman: Because I use my body in my work, and have since I began using photography and video, I am interested in exploring the subjective experiences I have as an inhabitant of my body. These are linked to being a white, cisgendered female. Again I think that it is important for me to try to call these identities out in my work, rather than expecting my body to be read as some sort of neutral ground. Jewelry specifically, and crafts generally, are also associated with females (as both the wearers and makers). My objects are then placed on the female body, so dealing with gender seems like a logical part of my work.

Why do you find body politics in the jewelry field to be so fascinating? Do current political climates ever influence the direction of your work with the body?

Lauren Kalman: I spoke about body politics a bit already, but I would add that of course current political climates motivate my work. I think that criticality is a necessary part of being an engaged citizen. My work often questions mainstream ideals and projects a forceful self-representation of a female body.

Have you seen or read anything thought-provoking recently? Could you share a few with our readers?

Lauren Kalman: I just started The Mother of All Questions by Rebecca Solnit. Summer is go time for me, though, so reading commences in the colder months!

Thank you.