Kristin Beeler, an illustrious American artist in the contemporary jewelry field, was one of the finalists for the Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant. Currently a professor and program head at Long Beach City College, Kristin examines the weight of beauty and memory through contrasting materials such as Tyvek, pearls, and charcoal. In this interview, we also talk about how anchoring memory to jewelry can help us contextualize new experiences in modern society.

Olivia Shih: Could you tell us about your background? How did you become an artist and educator?

Kristin Beeler: My earliest strong jewelry memory, as a child, is of little girls in my class bringing me their tangled necklaces because I was always the one who could untangle them. There are many similarities between being an artist and being an educator. Both occupations require a certain kind of curious patience, a willingness to slowly unpick a problem, and a desire to draw others in and show them something. They also both require buckets of research. Artist and educator are a symbiotic relationship that has worked well for me.

My undergraduate training was at Berea College, a small, private liberal arts college. It has a remarkable legacy of historical craftwork, a strong ethic of labor and service and commitment to social justice. I studied nearly equal parts ceramics, textiles, and philosophy while I apprenticed to a local jeweler who had just finished a residency at Penland School of Crafts.

I chose the University of Arizona for my graduate degree because of a love for the local landscape and desire to be close to family. My advisor, Michael Croft, was a gifted, low-key educator who taught me the value of being respected by one’s peers and understanding the supportive net of the jewelry community.

Since starting teaching full time, I’ve been fortunate to spend time working with Katja Prins, Iris Eichenberg, and many others who have invested in the continued development of my thoughts and skills.

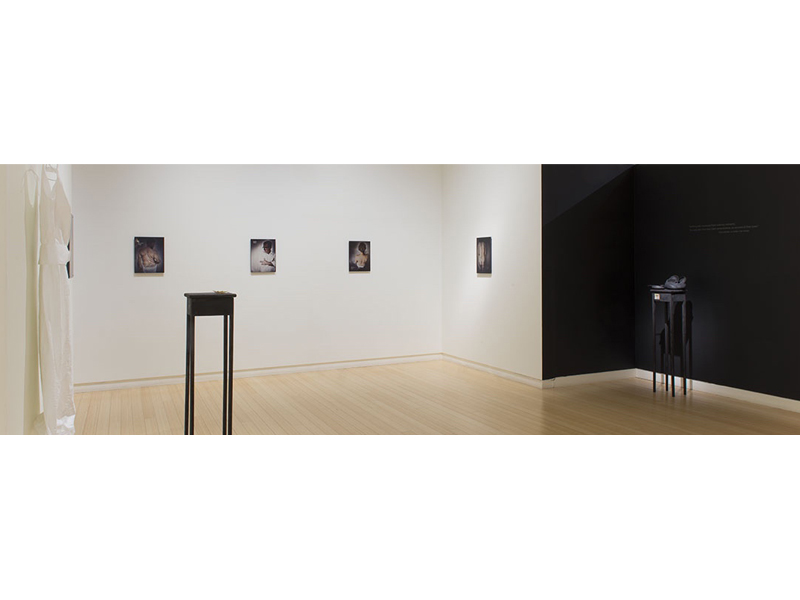

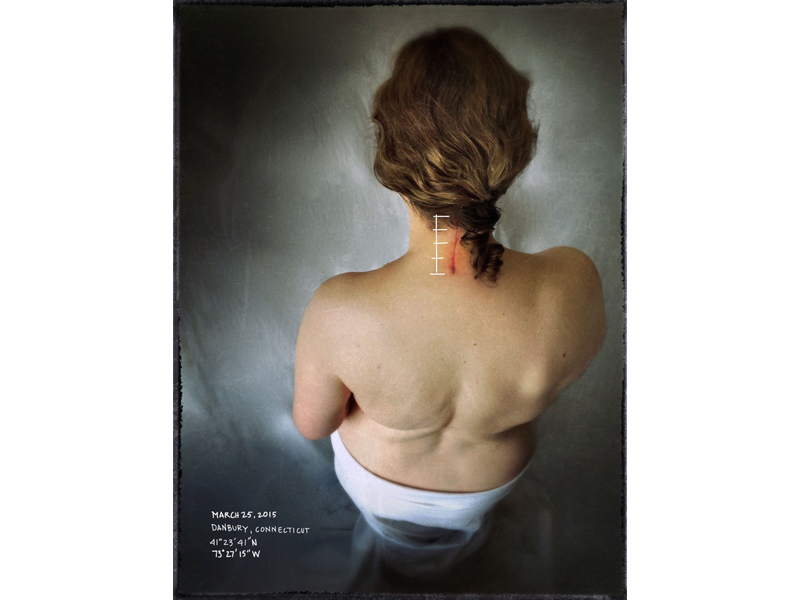

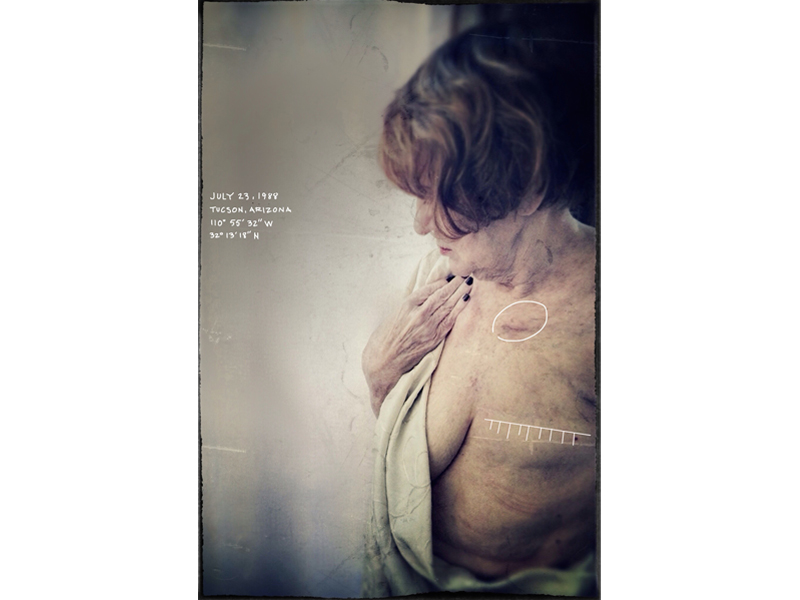

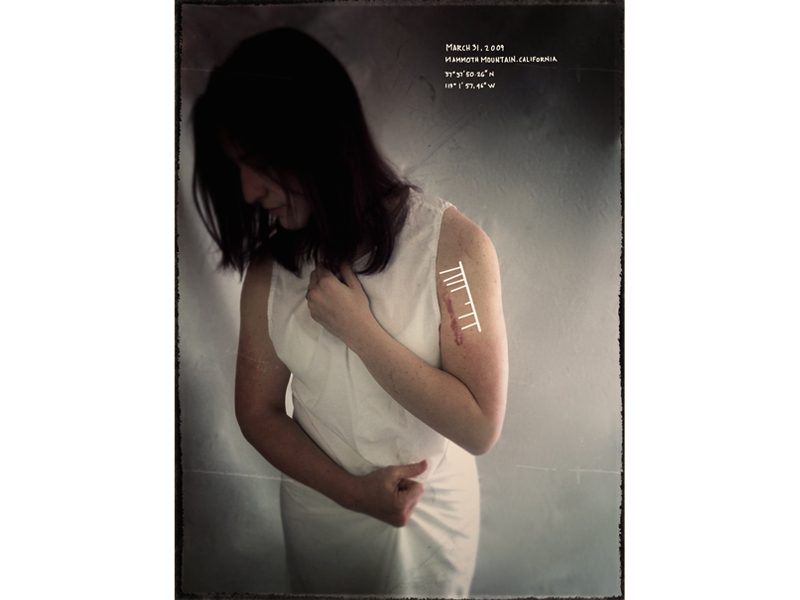

Archive of Rag and Bone, the prelude to your proposed grant work, is comprised of double portraits: a photo print of traumatic scarring on the body paired with a garment in Tyvek. The photo portraits are intimate but taken in various locations. How did you find the people in your photographs? And why choose to print their images on aluminum?

Kristin Beeler: In all cases so far, these were friends, colleagues, or acquaintances. I found that, as I started talking to people about my project, sharing stories of scars, many people would respond immediately with their own body-narrative, the breaking of skin being something that everyone understands intimately and sympathetically through their own experience. All the portrait subjects generously agreed to participate with varying degrees of anonymity. The process includes documentation of their story and its location in time and geography. We also discuss the process of repair as a concept. They view the project as an opportunity to see their experiences through a different lens and possibly transform the experiences of others. All subjects were posed based on historical classical or neo-classical postures, and photographed either in studio when possible or in whatever circumstances were available at the time.

Emulsion prints on metal have a particular way of reflecting light through the image that makes them glow very slightly. It’s far more luminous in person than a paper or digital image.

You chose to create garments in Tyvek. Why did you select this material?

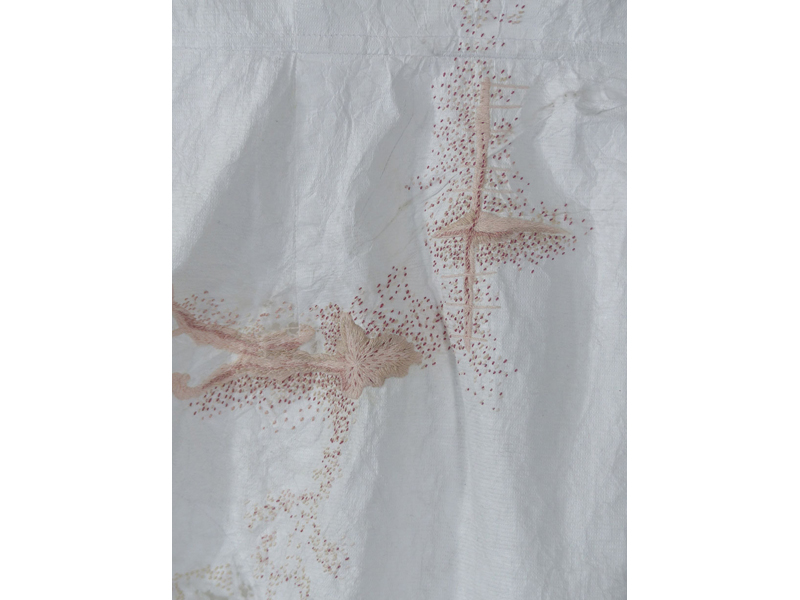

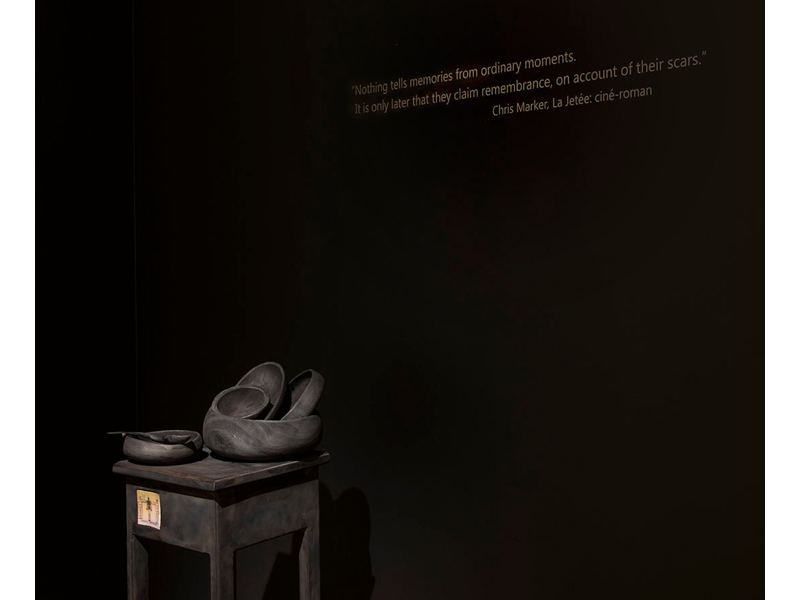

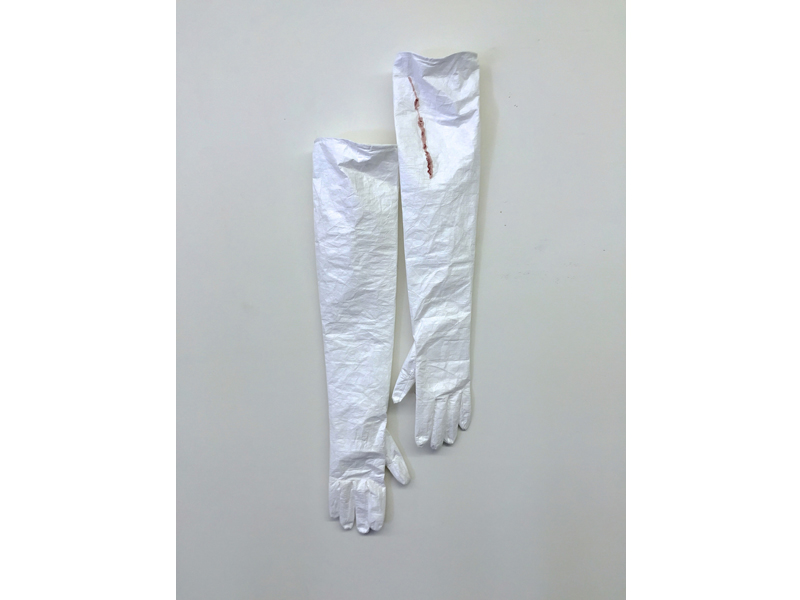

Kristin Beeler: Archive of Rag and Bone relies on the mythologies of materials. Tyvek, silver, mother-of-pearl, and charcoal contrast polarities: perfection and imperfection, permanence and ephemera, vulnerability and protection. Tyvek is a beautiful material: light, strong, with a texture between paper and fabric. Leveraged for its protective qualities, it gets used in housing insulation, hazmat suits, and postal mailers. And yet it’s a thin, delicate skin easily damaged under the right conditions. Embroidery is an obsessive process that requires the worker to languish on a small surface area, sometimes for days or weeks. Embroidering the Tyvek became a kind of protective talismanic ritual. The garments themselves are constructed to a couture level. In person, they have a slightly clinical, spectral quality. They’re meant to be in high contrast to the jewelry pieces, which use charcoal, carbon fiber rod, and mother-of-pearl. Charcoal is another material with a rich symbolic load: purity, reduction, concentration.

You say that beauty, memory, and the body with jewelry are running themes in your work, and your grant proposal was no exception. Where did your attraction to these subjects begin?

Kristin Beeler: Some kind of relationship to beauty is implicit to us all, whether its rejection or its pursuit. How we measure it and where we place ourselves relative to the scale is burrowed into our culture. I think a lot of what draws us into a subject is a certain amount of discomfort, being dissatisfied with known answers, a kind of curiosity. I spent many years researching the topic of beauty when I was challenged about my assumptions of it. The most interesting things happen in the places where we explore our assumptions.

In 2011, I wrote a meditation on beauty published in Metalsmith magazine.

With Archive of Rag and Bone, your work moved away from jewelry forms and gravitated toward photography, object making, and installation. Why return to jewelry for your grant proposal?

Kristin Beeler: My previous work was the result of research into various forms and deviations of beauty, expressed for and about the body, though at a much less ambitious scale. My conclusion from that was that native understanding of beauty originates in our primary tool: our own body and its relationship to the world. The body is a connector between the outward projection of personal adornment and the inward projection of memory, and so the skin, our envelope, becomes the boundary.

While developing this stage, I stopped making jewelry in order to reconsider the question. I focused on considering the body as location for personal history and intimate memory; skin as a boundary; and the repair marks of scars as self-identification and a kind of a priori jewelry. Jewelry and the body constitute primary locations for siting memory. Individual memories sit at the crosshairs of multiple associations, and jewelry is often their embodiment. So, now, I go back to making jewelry to bring the project full cycle.

The collection will expand to include jewelry objects—a kind of portrait/map—that allude to navigation of the body’s topography and the landscape of psychology.

You allocated a portion of the grant proposal for the creation of eight to 10 jewelry pieces, derived from navigation charts and based on portraits of scarring on the body. Could you talk a bit more about the introduction of navigation charts, specifically Polynesian Island stick charts?

Kristin Beeler: The format of the proposed jewelry is derived from navigation charts and mapping, in particular certain types of Marshall Island stick charts used for navigating sea currents that can’t be seen, only felt through experience. These models will serve as the visual basis for the composition of the jewelry pieces. Each piece will be rendered specific to the body topography of the portrait subject. While not exactly tailored to the portrait subject, each piece will serve as a kind of map, a device for navigating memory.

In your grant proposal, you designate the second portion of the grant for creating a book that documents your project. Why do you envision this book as small, precious, and reminiscent of a book of hours, which is a medieval devotion book?

Kristin Beeler: Everything about this project is about compassion and devotion. It has evolved slowly over a number of years. The book would be meant as an object of contemplation in itself, meant to make us slow down and question our assumptions of what’s beautiful or valuable or memorable. It’s my intention to create a book documenting and expanding the project and sharing it more widely as a collection of text meditations and imagery. The book form itself is a kind of locket or memory vessel. I envision this in a format based on a book of hours, small enough to be held in the hand, precious, accessible, and portable. Three essays for the book, running parallel to the imagery and content, will connect the work to a broader arc of thought. The strength and number of associations are the underpinning of the book as a memory event.

Three writers with an investment in our field and an interest in my project have already committed to contributing: Wendy Steiner, Professor Emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania and author of The Trouble with Beauty and Venus in Exile, has committed to produce an essay specifically for this project. My practice has been informed for many years by her writing, so her involvement is particularly gratifying. Suzanne Ramljak, author of multiple works on contemporary jewelry and editor of Metalsmith magazine, has agreed to write an essay based on her experience as one of the portrait subjects. She proposes developing Nietzsche’s thought, “As an aesthetic phenomenon, existence is still bearable to us,” as well as describing the transformative process of her own scar and exploring larger questions about the value and role of art. Dr. Gabriele Hauch of Saarland University, in Germany, has also agreed to contribute an essay. She has proposed a composition based on the concept of integumentum, an outer covering, skin, or envelope. Her perspective constitutes a trifecta and supports the overall premise of the book.

As you’ve noted in your proposal, Glenn Adamson claims that acceptance of contemporary jewelry moves forward slowly because jewelry is “too intimate, too close to us, and too difficult to radicalize.” Why do you think memory could be the key to working past this obstacle?

Kristin Beeler: Glenn mentioned this in a panel discussion at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art symposium for the exhibition Beyond Bling. He’s referring to an essay in the exhibition catalog, Blake Gopnik’s Crown Jewels for a Philosopher King.

Again, I think the interesting bits are lodged in our assumptions. I suggest that memory is a key but that perhaps we don’t have the language to articulate it in the right way because, as Glenn suggests, it’s too familiar. Jewelry is more than a symbolic reminder. A grocery list is a symbolic reminder. Jewelry is an emotionally charged, code-conscious, densely layered meaning bundle that is carried on, with, or through the body, often daily, often for years on end. Jewelry is a physical presence that we choose to weigh ourselves down with. We must carry it with us. Sitting on a shelf, it differs from a jewelry-shaped sculpture because, intrinsically, jewelry only has two positions: either on the body or waiting to be on the body. The plinth isn’t jewelry’s natural habitat. If we observe the jewel, we are reminded. But when we wear it, it weights us physically. It becomes a prosthesis for something not present. Through willful act, we must literally bear the memory object with its origins and its associations. We, personally, must bear the gaze that it draws. We yoke ourselves to that memory object and all that it represents. We carry it over borders, sew it into our hems, pass it to the next generation.

Tying jewelry to memory provides a unique entry point and allows audiences to create more complex, layered relationships to a jewelry object. I’m interested in playing between stored associations (memories) of what’s “beautiful” and “jewelry” and seeing how far the connections can be stretched before they break.

We live in a time when our memories are becoming one of our most precious natural resources. “New” occurs at an unprecedented rate. We are always actively searching for ways to stabilize and contextualize the new. Knowing how to map, navigate, retrieve, guard, and interpret memory is a counterpoint to a world fearful of personal and cultural dementia. Jewelry, with its implicit memory associations, has a role to play. The interaction of jewelry and memory deserves much closer study.

Have you come across anything curious or thought-provoking lately? Could you share what you’ve seen, heard, or read with our readers?

Kristin Beeler: My favorite new book lately is The Lost Art of Finding Our Way, by John Edward Huth, Donner Professor of Science in the physics department at Harvard University. Recent advances in brain mapping (and therefore memory) have led to an increased need for understanding navigation systems, and that led me to thinking about navigation. If that book is too much for a summer read, try reading the magazine article The Secrets of the Wave Pilots.

I’m also very excited about Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. This is an amazing book showing the work of the father of neuroscience, Nobel laureate and artist Santiago Ramón y Cajal. His studies of the anatomy of the brain are flat brilliant, as is the scope of his work. If you’re in a town that’s hosting the exhibition, please go for me.

Thank you.