Susan Cummins: Ken, can you tell me the story of how you became a jeweler?

Ken Bova: Interestingly (at least to me anyway) while in high school I bought a set of jewelry tools (pliers, a saw frame and a few hammers). I tried to teach myself how to make silver rings and bangle bracelets (without much success I might add) but abandoned it after entering college to study art. The stage was set before university, but I just needed the right nudge and opportunity.

I was working on my BFA with a major in painting and drawing when a professor hired me to help hang wallboard in a studio he was building. Part of this studio was dedicated to a small jewelry making space. In exchange for the help,

I was paid in part with six weeks of jewelry casting lessons. I was hooked. I was only a semester away from getting my degree when I decided that this was it—THE discipline I wanted to pursue as an artist. Because the school had no program in metals, I finished the degree in painting and then transferred to the University of Houston. I studied for a year of post-baccalaureate work with Val Link and Sandie Zilker before applying to graduate schools.

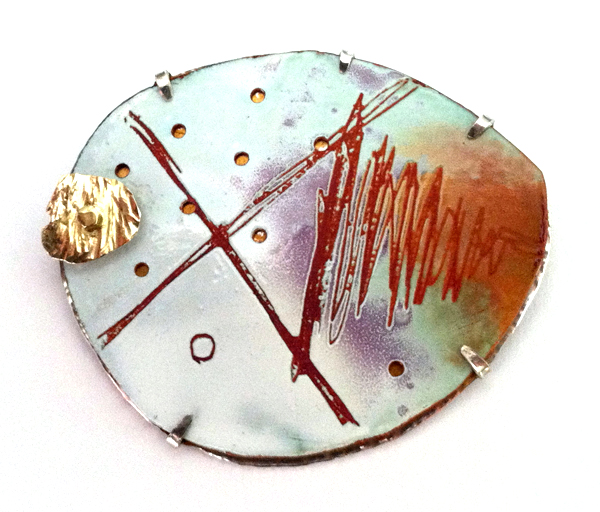

I was convinced I wanted to be a smith and concentrated on raising and forming processes. In graduate school, however, I found myself inexplicably drawn to the wearable—perhaps because of its intimate scale or maybe because working with the brooch format was comfortable and echoed my experience in painting. In any case, I gravitated towards jewelry, and there I’ve stayed.

By the way, I still have the very first piece of jewelry I cast, a sterling silver and tumbled jade stone ring.

Susan Cummins: Ken, can you tell me the story of how you became a jeweler?

Ken Bova: Interestingly (at least to me anyway) while in high school I bought a set of jewelry tools (pliers, a saw frame and a few hammers). I tried to teach myself how to make silver rings and bangle bracelets (without much success I might add) but abandoned it after entering college to study art. The stage was set before university, but I just needed the right nudge and opportunity.

I was working on my BFA with a major in painting and drawing when a professor hired me to help hang wallboard in a studio he was building. Part of this studio was dedicated to a small jewelry making space. In exchange for the help,

I was paid in part with six weeks of jewelry casting lessons. I was hooked. I was only a semester away from getting my degree when I decided that this was it—THE discipline I wanted to pursue as an artist. Because the school had no program in metals, I finished the degree in painting and then transferred to the University of Houston. I studied for a year of post-baccalaureate work with Val Link and Sandie Zilker before applying to graduate schools.

I was convinced I wanted to be a smith and concentrated on raising and forming processes. In graduate school, however, I found myself inexplicably drawn to the wearable—perhaps because of its intimate scale or maybe because working with the brooch format was comfortable and echoed my experience in painting. In any case, I gravitated towards jewelry, and there I’ve stayed.

By the way, I still have the very first piece of jewelry I cast, a sterling silver and tumbled jade stone ring.

Perhaps because of your education in Montana and Texas and the imagery you often employ, I think of you as a Western American jeweler. Does that description fit for you?

Some of your jewelry carries small bits of junk and mementos, such as in the brooch called The Preservation of Memory. What is being preserved here? Is there a story implied?

Ken Bova: In her introduction to On Jewellery, Liesbeth den Besten said that, “A piece of jewelry is one of those small and intimate artifacts completely suited to remind one of a person or an important moment in life.” I think this is about as accurate a statement as one may make about the nature of jewelry to both evoke and convey recollection.

As you say, much of my work carries small bits of junk, the ephemera of the quotidian, and these bits are often minuscule mnemonics for events and experiences both in my life and in those of my family, friends, and colleagues. The Preservation of Memory is part of a (so far) three-piece series that memorializes relationships. Each carefully selected element is either a souvenir or reference to aspects of my experience of another person. And, like those great Time-Life art books with the series title “The World of (fill in the blank),” each element refers not just to the individual, but also to the context in which the experience occurred. They are visual puns and clues to events and places.

Ken Bova: When I was an artist in residence for the Montana Arts Council some years ago, I used to teach in elementary schools throughout the state (and it’s a big state). When I’d ask the second and third graders in each school why people wear jewelry, they’d almost always respond with the same four answers. Keep in mind that the responses were shouted with extreme enthusiasm. (These were, after all, second and third graders getting to make jewelry for a week.) The first answer was usually “to show you’re rich!” which I translated into conveying wealth and status. The second answer was “stand for stuff” which meant to symbolize or signify. Third was “to look cool” meaning attraction and allure. And the fourth and final was “for fun.” This was a little harder to define but basically came down to play and fashion.

I think those seven- and eight-year-olds pretty much nailed it. Sometimes jewelry is worn for a single aspect, and other times it’s for more or all of them. That’s a lot of information for a small wearable object. Jewelry can carry virtually any idea or feeling limited only by the intent of the maker.

Right now, I’m exploring issues of death (loss) and memory with color as one element acting as a vehicle for narrative content and emotional response.

You have taught at many schools, and for the past few years you have been an assistant professor at East Carolina University (ECU). The program there seems to be an active one. Can you discuss something about how it differs from other schools?

Ken Bova: I think East Carolina University’s metal design programs differ from other schools in a very significant way. It is atypically one of the largest programs in the school of art and design and has the largest graduate program in the school. Five faculty are associated with the metals program, and all are dedicated to fostering a creative environment and familial atmosphere to explore the field. Couple that with a semester abroad program in Italy that features a fully equipped metals, jewelry, and enameling studio administered and taught by Linda Darty, and I believe ECU has a program that offers outstanding opportunity for study in jewelry and metals.

You often work in enamel. Can you tell me something about its resurgence?

Ken Bova: I think the resurgence of enamel has been led by a number of highly skillful and insightful makers whose work demonstrates the versatility and expressiveness the medium provides. They’ve brought the material and its techniques to the attention and into the studios of both universities and the workshop. Aided by The Enamelist Society’s efforts and a wealth of new publications focusing on the medium, the enameling process has become increasingly accessible to younger makers.

What does your studio look like? Orderly? Messy?

Controlled chaos. Really, sometimes I think my bench is a fixed point in the universe where entropy is most concentrated.

Only one? I’m an avid reader, and my preferences shift from fiction to nonfiction and back. I’m in a nonfiction mode at the moment. I’ve just finished Philip Ball’s Bright Earth: Art and the Invention of Color and A Perfect Red by Amy Butler Greenfield. Both explore color and its relationship to art and commerce. My bedside stack of books to read include Camille Paglia’s Glittering Images, On Poetry by Glyn Maxwell, and Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonders by Lawrence Weschler (a recent gift from a workshop student about the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles), among others.

For fiction, The Elegance of the Hedgehog by Muriel Barbery, The Sparrow by Doria Russell, and I’ve just started The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón.

To be perfectly honest, I don’t really read too many jewelry-related texts other than the occasional essay or article in various periodicals. So, I’m afraid I must disappoint you on that count. That being said, recent books on jewelry that I’ve purchased include the aforementioned On Jewellery by den Besten, Push Jewelry curated by Arthur Hash, and Empty House by Robert Smit.

Thank you.