Now in its second iteration, the Mari Funaki Award for Contemporary Jewellery is an international biennial award founded in memory of the life and legacy of its namesake, Australian artist Mari Funaki. In this interview, Katie Scott, the director of Gallery Funaki, elaborates on the ways the award has grown since its inception, and her hopes for the award in the future. In addition, we ask the 2016 awardees, David Bielander (established) and Sarah Johnston (emerging), about the meaning behind their works.

Adriane Dalton: To start, give an overview of the history of the Mari Funaki Award for Contemporary Jewellery. How was it conceived, and what are your goals for the award?

Katie Scott: I started the Mari Funaki Award as a legacy, a mark of respect for Mari. Time moves so fast, and I wanted to keep her name alive for a new generation of makers, as well as provide a platform for this new generation to share with more established makers. For Australian audiences, it’s also a rare chance to showcase even just a small snapshot of what’s happening around the world.

This is only the second time around for this biennial award. How has the award changed since the inaugural year?

Katie Scott: The most notable development is the partnership we’ve begun with the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV). The winning piece (in the established [artist] category) is gifted into their permanent collection, and over the years these pieces will form a valuable addition to the public holdings in contemporary jewelry in Melbourne—a collection in Mari Funaki’s name is the best way I could think to pay respect to her life and work, and build a legacy.

We also raised the prize money from a broader donor base this time, which is something we’ll keep building on, as those relationships support the future of contemporary jewelry in very tangible ways. Clients have begun to approach the gallery wanting to be involved as they can see the impact the project has, particularly for students and emerging artists.

Finally, we instigated an application fee this year. The funds raised from that allowed me to actually cover the administrative costs, hire some PR support, and there was enough left over to produce a brochure/poster that’s available for free to all visitors and is a great souvenir for the artists involved.

Has the number and scope of applicants grown since 2014?

Katie Scott: This year, as I said, we instigated an entry fee for the first time, so we were expecting a drop-off in applications—but actually I was surprised at how small the drop-off was. What’s interesting is the breadth of locations those entries came from: 48 countries this year, as opposed to 35 in 2014. There is a real sense that contemporary jewelry is a growing movement, which is really exciting.

As gallery director, what is your role in administering the award? Are you the sole initiator, or do you have a team or board that works with you?

Katie Scott: I’m the sole initiator, which involves raising funds for prize money, establishing partnerships and sponsorship, PR, designing the exhibition itself, and overseeing the project as a whole. I work closely with Chloë Powell: As award manager, she deals with all the logistics, the technical aspects—software, forms, and so on. She also handles all the communication with applicants and compiles and sorts the large amounts of information generated by the online forms.

How were the jurors selected for 2016?

Katie Scott: Our judges this year were Catherine Truman (a world-renowned Australian jeweler based in Adelaide), Simone LeAmon (the Hugh Williamson Curator of Contemporary Design and Architecture at the NGV), and Kate Rhodes (a senior curator at the RMIT Design Hub).

I wanted local judges who would bring a particularly Australian eye to the award, and though I was keen to have expert jewelry opinion on board, I also wanted perspectives from beyond the jewelry community—specifically from the very vibrant design community here in Melbourne. It was important that the NGV have a presence on the panel, given their stake in the outcome, and we were very fortunate to have three such highly respected, insightful, articulate women make the final decision.

Describe the selection process for the short list. How does the jury review the submission materials? What are the criteria they are using to narrow the selection?

Katie Scott: Chloë Powell and I are the curators: This is not an exhibition by committee. I’ve always been very clear about the fact that Gallery Funaki is a private, commercial gallery with a set of subjective curatorial parameters, and that stands equally in the case of the Mari Funaki Award. We choose jewelry that speaks to us—that has concept, technical skill, innovation, a resounding and authentic voice. Even if it’s something indefinable but resonant; that can be enough. It’s not an exhaustive or objective list of the best work being made at this moment—rather, it’s a curated snapshot that makes a statement about what we believe compelling contemporary jewelry to be.

In an Instagram post announcing Sarah Johnston’s award for the emerging [artist] category, there was a quote from the judges reflecting on the feel of the piece when worn. This stood out to me because of the ubiquity of digital applications. Jewelry is typically judged first and foremost by how well the work is presented in a photographic image. What role does the experience of wearing the work play in selecting the awardees? Do the judges spend time experiencing each piece of jewelry on the short list before making a decision?

Katie Scott: While we do select the artists who will take part in the exhibition from their submitted photographs, the process of judging does rely very much on a haptic experience of the works. That was one of the most rewarding aspects of the judging process, in fact; the judges spent many hours, as a group, discussing every piece in the show. For each artist, the work was handled and worn, so the judges could address each piece in depth. It was a very focused process—Simone, Catherine, and Kate joked afterward that it was like a judging master class.

The established artist award is acquisitive, with the work being purchased by the gallery and gifted to the National Gallery of Victoria. How did you establish this relationship? Was there ever a worry that the NGV’s participation would influence the choice of the awardees?

Katie Scott: It was simple—I approached the NGV and they readily agreed to the idea. The institution has a significant collection that goes back to some very important works from the 60s and 70s. And no, I was never worried that their participation would influence the choice of awardees. The process was absolutely transparent and the judges completely professional and fair-minded.

The 2016 awardees, Swiss artist David Bielander (established) and Australian Sarah Johnston (emerging), exemplify exquisite craftsmanship joined with compelling conceptual approaches. Both artists seem to be delighting—to varying degrees—in visual provocation. What was it about these works that set them apart?

Katie Scott: I think precisely what you’ve pinpointed—the concept combined with the craftsmanship, and the visual provocation this combination brings. The judges commented, “we’re rewarding skill and craftsmanship in the winning works but in the company of potent ideas.”

Of Bielander’s piece, they said, “the idea is in the execution, without that execution the concept would not be delivered. It’s an extraordinary example of contemporary making and practice, an example of making that expresses things unlike in any previous time. There is simplicity and reference to childhood play, but a sophisticated twist that flips it from play to something very serious, and that’s a hallmark of his work.”

And of Johnston’s piece, Collapsing Time, “this is a surprising piece, the materiality is beautiful. It’s like a tempest, a storm. This piece is about so many things; the intimacy of putting something on and feeling yourself transformed, taken to another place.”

What are you hopes for the award in 2018?

Katie Scott: I hope we’ll build on the success of the award so far and make it a sustainable, ongoing project with a real legacy.

Questions for David Bielander

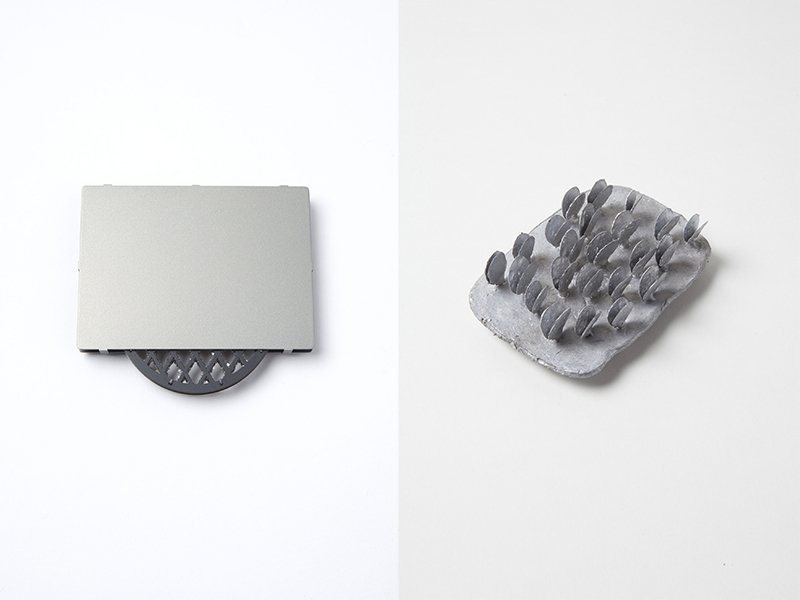

Your selected work, Cardboard, is a remarkable visual deception! It has already often been written about, including in these pages. However, I am curious to know what it means for you. Can you tell us about this?

David Bielander: I am the author of this work. The reason for materializing an idea of a certain complexity, and afterward deciding to publish the outcome, is in order to exactly not tell about the intentions in spoken language. The materialized object captures the complexity and contrariness of a thought far deeper than words can.

The primary sensation is not visual: The piece behaves like cardboard more than it looks like cardboard. The wonder starts when you grasp it—in both meanings of the word. That is why it is jewelry. I build on the two so very different tasks of this work: to be an autonomous object and to appear on a person.

We perceive things solely in relationship to something else. As soon as a tiny shift in the context occurs, it is enough to make us perceive a thing differently and in a way that we have never seen it before. Things do not stay as we perceive them at first glimpse. It is the ambiguity, the multifacetedness of the nature of things.

It is part of the conditions of our existence that it is impossible to arrive to definitive truths, because truth is dependent on perspective. In that I materialize the ambiguity, the multifacetedness of a presence, I want my work to show me something that is the truth, almost in a transcendental way. Of course I will fail in the end, but I flirt with the potency to make tangible something that is true.

This work seems to be part of a larger conversation in the field in which alternative materials have taken precedence over traditionally precious materials. Is your intention with this work to turn that idea on its head?

David Bielander: You mean: finally real “cardboard democracy”?[1] 😉

No, this is not the intention. Of course it can function like this as a kind of side joke within the field, but I don’t tailor works for this bubble. It is exciting to discover a really great work in cardboard.

How did you decide to submit this particular work for consideration?

David Bielander: It is a good piece. The reason to take part in this competition is the respect and gratitude I have for Mari’s, and now Katie’s, extraordinary work in Australia.

In the cardboard I see a (conceptual) connection to Mari’s approach, a bit “Mari goes figurative.” The tricky thing with these striking and blatant pieces is that they make good photos and get published a lot; the “field” you spoke of is already weary of it, but it is a work that is only a bit over a year old and still needs to experience lots of different contexts and can make a good contribution to an event.

The other tricky thing is that it is an acquisitive prize. Whereas you obviously want to put forward a strong work, you also want to make sure that the piece you send is not too expensive. In that respect I find an acquisitive prize an ambiguous thing.

Questions for Sarah Johnston

What is the meaning behind the title of your work, Collapsing Time?

Sarah Johnston: Collapsing Time is about making connections in the real world and keeping those connections online, it reflects our global lifestyles and how there never seems to be enough time. The work discusses online culture in how we are constructing relationships—personally, spiritually, and romantically. The Internet is a vast portal in which our emotions, memories, and subconscious thoughts are recorded and streamed through digital technology. We meet and grow to love our friends in an online environment where our concepts of times are affected; essentially it feels like time is collapsing because every moment can be recorded and multiplied. I wanted to make a jewelry piece that was representative of this collapsing time and symbolic of our love of one another online.

The materials—onyx and rubber—have a shared surface quality that makes it difficult to discern them from one another. How is the piece constructed, and why did you choose these materials?

Sarah Johnston: I work primarily with stone, which carries a sense of weight and time beyond human existence. Using stone as a creative material therefore changes the piece’s capacity to store time. The choice to work with stone and the rubber Internet cable casing came from ideas based on recording history and present moments in time. Their shared surface quality was serendipitous; I had completed carving the stone when I discovered that the inside of the cable matched. It felt like a subconscious decision; that somehow the materials reflected one another’s qualities yet remained under each presence of their own meanings.

Is this piece part of a larger body of works on the same theme? Why did you choose this particular work for submission?

Sarah Johnston: Yes, there are further works that were created that all have this recombination of forming and unforming; to turn and twist and rejoin. These forms are meant to represent how we are paradoxically both more in touch and more removed from one another. I chose this particular work because it possesses a certain spirituality and evokes a sense of mystery that is yet somehow familiar. The work resembles something we can only imagine as parts of time collapsing.

INDEX IMAGE: Katie Scott by Roswitha Aigner

[1] “Cardboard Democracy” refers to a series of works by American jeweler Shari Pierce.