Aaron Patrick Decker: How did you come to jewelry?

Kadri Mälk: Initially I studied painting for four years and really enjoyed it. Before that, I worked in a publishing house. After studying painting, I suddenly felt that maybe it wasn’t for me, maybe I needed something more intimate. After that I went to the Academy to study jewelry. I was either 28 or 29 when I graduated. I felt somehow that I was late, an autumn flower. I remained a freelance artist and was on my own for about nine years; meanwhile I was invited to teach. Initially it was just a small workload, like once a week. I enjoyed staying in my atelier and working on my own schedule and freedom. I liked it so much, no due dates and a kind of wild life, a lifestyle I still really appreciate.

After graduation I began some studies in stonework. First in St. Petersburg in a stone-cutting factory, a huge factory that received quite high-quality raw materials from Siberia. Then I studied gemology in Finland at the Lahti Design Institute for two years. I was offered to prolong my studies in London in 1993–94 and receive the highest degree one could get in gemological studies. During that time in Estonia, there was no one in the field of gemology. It’s a small field in general, but in Estonia, no one had this sort of certification.

But then my professor, Kuldkepp, fell ill and couldn’t return to the department anymore. Until this point I had worked alone. Leading a department is not just about being an ideological leader, there are other concerns about finances, and finding a team that works. You have to find people who fit together. I had no experience in this work so I was very afraid of the proposal to take the department. And especially since I was offered the gemological certification, which was seductive.

We began at 7 a.m. and the first break was at 10:30 for some coffee. It was very tight and regimented. Funnily, during lunch they turned off the power in the shop; I thought I could work more during this time, but it was not allowed. He didn’t believe in the beginning that I could learn facet cutting, but at the end he was happy with where I got. I remember having a notebook and just trying to write down everything during lunchtime. I wouldn’t eat. I’d just write what the workers were saying. The old knowledge. It was my passion, stones.

You have said you were close with your professor; can you talk about your decision to take over the department?

Kadri Mälk: She was the reason I decided to take over the department. It was kind of fatal serendipity—as I saw it then, but not anymore. I had to do it because she could not. She was an extraordinary personality in the time and circumstances, she did not fit the environment, didn’t fit the times. If you read her writings, you could tell she had such a drive sourced from somewhere else. She had such a mission to pass on things to people, not in a direct way but in an indirect and metaphoric way. Her teaching methods were not pedagogical at all, she was often much more abstract. She locked the students in the room and said, “Just work.” All should be concentration, creativity driven to the work. No cinema, no theater, no magazines, no outside information, and it should all come from yourself, come through you. Extreme methods, but very effective. She wanted you to achieve the maximum. She was not very communicative, didn’t go anywhere, didn’t move around, her efforts were very concentrated on certain students. I can’t find the right words to completely describe her, but she wanted students to open up by closing off.

Do you think becoming a professor so early shaped you as an artist and continues to shape you?

Kadri Mälk: I was a baby professor. I was elected when I was 37. I had already been a renowned artist for some time, but as an educator, administrator, or team member, I had no experience. Looking back, I realize now the trust from admin and colleagues when I took over the department. My creative past supported me and proved to them I could survive in the school. Just recently somebody outside of the academy, and artists, came to me and said, “Now, Kadri, I realize you have done it well…” In the beginning, others were hesitant because I was seemingly unsuitable for the job. The highest hesitations came from me. I was unsure if I could rise to the occasion. And when the women came, 15 years later, it was some confirmation.

I just liked to make my pieces. And it’s so funny, I still go about my work in a similar way. Nowadays students are much more oriented by a schedule and thinking about making work for exhibition. Deadlines. My satisfaction came from my pieces, from the process. I liked how they came to me, how they happened. When I was in school, learning about the art field was not included. The professor tried to keep this off us, all these associations, how this works, etc. I remember asking her what happens when I graduate. She didn’t tell me anything about the real life of artists. It was all about the work. It was a conscious decision to keep the art world away from us.

Do you think your work changed during this period?

Kadri Mälk: No, not because of the Academy. The majority of my time went into the Academy, but this didn’t affect my work. In the first years, we gave assignments to students in the form of certain themes. Later on, especially at the MA level, where the study is more conceptual, they must meet their choices themselves to reinforce their spiritual identities.

Someone asked me, “What do you like best about teaching?” I feel lucky that I have the possibility to notice and follow how personalities develop and begin to blossom; how new talented personalities emerge in a creative surrounding; and how they act and react. And how passionate they may be in their work! It’s the achievement of every member of our staff.

Not much changed about me, either. Of course I had to modify my talking towards topics, concentrate, and learn to convey or see the methods that worked best, but at the core I didn’t change.

It’s very different to be just a teacher rather than the department leader. You are responsible for all that happens. The biggest difference is that the academy and the students are number one, followed by your work and your family. The academy and the students are number one. They can call me at any time if they need. I feel better in this. They know that they can come, they are not lost.

I think that’s quite admirable. I haven’t heard of another professor so invested in the program in the ways you are. What do you think some of the most important things to pass on to your students are, what do you hope they take away from you and the Academy?

Kadri Mälk: A kind of attitude, that you should believe in yourself. People shouldn’t take you off your path. Younger artists are vulnerable, in a condition to be shaped or reshaped; it’s important to tell them or convince them that whatever happens you should turn that attention in to yourself, otherwise you get lost. If you take into consideration all the opinions you hear, you get lost; there is so much noise. You don’t know where to look or where to go. You don’t orient yourself any longer in the world. Believe in yourself … it’s hard to when you’re young. Believe and be strong in your core.

Kadri Mälk: Yes, it becomes stronger. It crystalizes, the elements that are more important, the ones that are harder, take shape, and the rest falls apart. It comes with time, you shouldn’t force or exaggerate. You have to be patient.

There are so many conferences, so many books asking the big question—is jewelry art? It’s not my task to answer it.

My comment to it is very simple: love me or leave me or let me be lonely.

Or to put it differently: take it or leave it or let me be lonely.

What do I mean with that? It’s very simple. There is always another way out. It’s not only taking or leaving. There is another possibility which is hardly seen. You just have to be patient and look carefully.

Also, the creative process has confusion, has crisis. You should not be afraid of these things, they are natural. Fear that your next work will fail is so very normal. Crisis is normal in art making. Art is always about starting again in hesitation.

What are your impressions of younger jewelers now coming into the field, at large and in Estonia?

Kadri Mälk: (long pause) It is very hard to generalize, even here the local scene is quite diverse. You can see more design-oriented work, more personal work. I try to encourage these people who are afraid of having somehow veiled, personal, or exceptional ways of expressing. If they compare themselves to what is happening in different places with people their age, they begin unconsciously to bring other aesthetics into their own work. I want to encourage people who are different, who are slightly insecure.

Francis Bacon said, if you are going to decide to be an artist, you have got to decide that you are not going to be afraid to make a fool of yourself.

Making art is so simple—all you have to do is to wait quietly, staring at a blank wall until the drops of blood appear on your forehead. Be aware that criticism always comes along with creative work. If you can’t handle it, you have to quit.

How frequently and easily success transforms into depression! You can avoid it by leaving some loose threads in your work, some unresolved part that carries you forward in your new work. What you need to know in your next piece is silently present in your last. You can find it while looking in patience. It’s like a seed crystal for your next destination.

I am not really analytical like most. I am interested mostly in my unconscious choices, what I like and what triggers me.

Kadri Mälk: Look at the originals. You should look at the original pieces and see for yourself.

Do you think that is an important idea, to see things in person?

Kadri Mälk: Yes. We are so much in the age of reproduction. We see the screen or the page with the picture. We don’t look at the original anymore, we don’t feel the tactility of the pieces or taste the iron. It is very harmful to humankind to go about it in this manner. Go to the originals. Otherwise it is so meta-meta, you don’t feel, you don’t know the scale, the details, or the material from the copies.

What are some of the things that inspire you?

Kadri Mälk: I don’t know what inspiration is exactly. Sometimes things are more intense and sometimes less intense. Sometimes I feel that I can capture things, forms, colors, something in the air, and sometimes I feel like sand is running through my fingers.

Consciously I cannot, but it comes more from my subconscious. There’s some differentiation between mental and physical subconscious. One is staying here (Mälk points to her head) and one is here (she points to her stomach), the first is mental and then the second is more gut, subconscious. The feelings are very different. Or maybe the frequencies are different. I like life in all its expressions, that’s my source.

Kadri Mälk: Usually it’s subconscious, these decisions you make. They are made before they are at your conscious level. You made the decisions in a big fog. Just as in crystallization, they come into being. And when they are there, it is your choice to call them either consciously made or born out of the sky.

Looking at your work, there is a quality of instantaneous moment; going deeper, you find more and more. The work is quite striking and emotionally charged. Seems very palpable, like it has a heartbeat. There is also a melancholy quality to many of your pieces. Is that a conscious decision or a more subconscious one?

Kadri Mälk: A tiger cannot avoid his stripes! (She laughs.)

That’s a great analogy.

Kadri Mälk: I am very shy describing my work. I am afraid I cannot reach the truth through verbalization.

There is this quality of Estonian jewelers, not a reluctance, but an ability to keep the integrity of the work. It’s hard to describe the work prescriptively in its conceptual and formal functions, often it acts like poetry, it speaks with power but is not completely resolute. What is your opinion of this attitude?

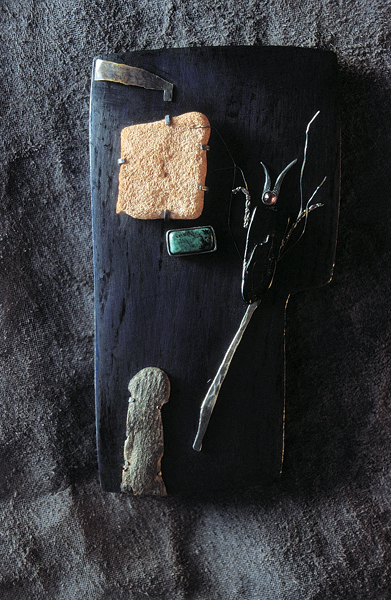

Kadri Mälk: When I think of my jewelry, it’s easier to describe it. “It’s blue, violet, black, and purple. There is fog, there are shades of magenta.” You can be precise without being clear. And unclear may also be precise. It’s very much an oxymoron.

Kadri Mälk: It’s really a sort of hologram, like a puzzle. As a notion and phenomenon, I think it’s possible.

It is an interesting facet of Estonian jewelry. Sort of irresolute.

Kadri Mälk: Yeah, it’s in a stage of becoming. Being on the way.

Yeah, it’s not negative, its more open.

Kadri Mälk: Yes, an ambivalence.

Is there something that you want people to get from your work?

Kadri Mälk: To share the unsharable. What often happens is that the viewer approaches in a superficial way, which is natural. On the foreground they see materials, especially if there are unusual materials.

I’ve used a lot of moleskin in my work and it’s taken a kind of attraction or peculiarity in my work. I don’t feel a need to explain the choices I’ve made. How it came to me, it was just an incident. Or a happy accident.

When all my stuff was stolen from my atelier, I found a coat of my grandmother’s from the war, made out of moleskin. I took it apart, slices of extremely thin, like silk, soft silk paper like. Then I saw these pieces. The tenderness at first, the sensuality of the material, and that the fur grew in only one direction. It was so thin, the fur. It had such a strong character, though. I started to work with this, used it a lot, the coat is now gone into all the pieces. I also think the animal is present in the work. The mole, he’s blind, he doesn’t have sight but has extreme animal spirit. All this orientation in time and space. I studied how they moved, their lives, did more research. How they were trapped and caught. This animalism was powerful and important for me in these works. But you aren’t going to retell the story. If you put it into a story, it’s banal.

Kadri Mälk: When I carve it, like timber or wood, it has nerves like a human body. The stones have structure, they direct you. They tell you where to go. You should go there and you shouldn’t make the wrong decision. There is a negotiation with the stone when I cut it. Jet is mute, silencium. Only a big dust is coming. Your lungs are filled with jet powder. Like stones are directing you in advance, there are inclusions, by heat they will crack more. Jet is completely mute. This is what fascinates me. It’s not much used in jewelry anymore.

I lack the habit and custom and will to interpret my works after they have been completed. The work either tells you something or it doesn’t. Once you have completed it, then keep quiet. The work must know whether it radiates or not. The piece of jewelry in your mind, in your imagination, is always correct and beautiful. Resistance starts when you try to convert it into material. Oh, la la! Materials are like elementary particles—charged, heavily charged sometimes, but indifferent. They don’t tell you much, you have to tell them the truth.

You have staged events and produced a number of books—JUST MUST, Castle in the Air, etc.—about Estonian jewelry and jewelers. You have made the work coming from the Academy available to a much larger audience. Give us your thoughts about publishing these books and what your intentions were at the time you did them.

Kadri Mälk: Firstly, I love books. I love their smell and the shade of the voice when you turn the page and then unexpectedly see a new image … It’s both emotional and intellectual. Since 1989 I have published twenty-something publications, some of them out-of-print already. The first ones were really ugly ducklings, black-and-white … I’ve strived always to tell something different with them, it has been my passion. Indeed, they have been acting as ambassadors of Estonian jewelry in the world, although it was not intended. So many students coming from abroad have said the pull came from the books. Strange! Usually nowadays the urge comes from the Internet.

To make an impression abroad is not as important as to make an impression in your own soul.

Thank you.