Susan Cummins: Can you tell us the story of your education and how you came to be a jeweler?

Julia Turner: I started college studying various things relating to language, not thinking I would end up in an art field although I’d been making things since I was little. At some point I took an art class as an elective, and that led to another, and another. In my junior year I went to Italy on a study-abroad program that combined language courses with studio art courses, and I think the change really happened there.

Susan Cummins: Can you tell us the story of your education and how you came to be a jeweler?

Julia Turner: I started college studying various things relating to language, not thinking I would end up in an art field although I’d been making things since I was little. At some point I took an art class as an elective, and that led to another, and another. In my junior year I went to Italy on a study-abroad program that combined language courses with studio art courses, and I think the change really happened there.

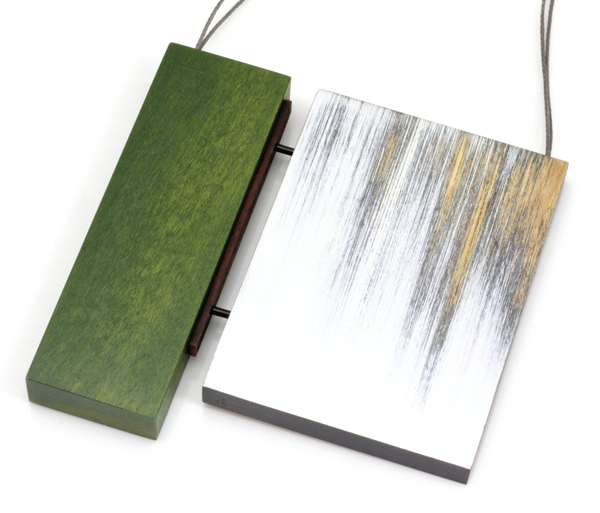

Julia Turner: My use of wood began maybe five or six years after I left school. I had done woodworking in art school, but didn’t think of it as a jewelry medium. I think I first grabbed a piece and carved a ring from it out of frustration with the weight of metal—I wanted more volume, more warmth, more color, and you can only do so much with hollow construction and patinas. Having familiarity with it from school was great—I knew something about the various types of wood, how to finish it, and so on, and jewelry tools actually worked really well on it for the most part. I had learned wood engraving in a printmaking class too, which is beautiful applied in jewelry.

You seem to have a fascination with rich surface texture and color. What do you use for inspirational source material?

Julia Turner: I take lots and lots of photographs, and I find myself getting fixated on a particular kind of object or feature in my surroundings and then I get a little obsessive about collecting more and more of it. Mostly it’s in cities; though I love getting to the woods, I find that’s where I turn work off—what happens in the studio is much more related to the constant game of building and breaking and patching that goes on in the city, which creates layers of information all around. I’m curious about that partly because I also make things, and it’s fun to read the lines and cracks in the roads and the weird transitions between old and new buildings and the capped pipes sticking out all over the place, and to try to understand what’s going on. It goes hand in hand with experimenting with materials in the studio—I’m curious about all of them even if I’m only working with a few right now.

But I’ve realized there’s also a common thread to the things I stop to take pictures of, which is that they all show a state of vulnerability. That’s a really good reminder for me since I can also be really stubborn in the studio. One of my favorite ongoing collections is paint spills. It seems all the paint buckets in San Francisco are leaky and the sidewalks are a gold mine of accidental drawings, some of them multiple blocks long, that wind around in gorgeous calligraphic arcs and swirls with little spatters coming off. They sometimes split and then re-join and get really interesting around a stoplight where the person had to stand still for a while, with the bucket swaying. I always imagine the person coming from a painting job that they performed very carefully with tape and a scraper, afterward unknowingly making a masterpiece on the way back to the truck.

Finding those reminds me to let materials unfold in more interesting ways, and to pay attention to what happens when I’m not forcing things. I use the city the same way to understand color. I’ve always felt really awkward with it and I decided to start documenting “impossible” color combinations with my phone to try and retrain my mind to think differently about them. It’s starting to work, but I feel like a beginner with color—I’m looking forward to a lot more experiments just with that.

Julia Turner: I do approach them differently, but less so now than in the past. Everything is starting to converge more as I move toward one-offs that are more modular, so that I can have help making them, and I’m feeling more free these days to try things with the multiples that are closer in feel to the one-offs. But generally I think of the multiples as distillations of the studio work. To put the constraint of reproducibility on work that’s about exploring and growing would really limit where it could go, but to arrive at designs for multiples just by experimenting without a thought about how to reproduce them makes it really hard to move forward.

So when I have a show I use it to move toward what I’m curious about without worrying a lot about production, but out of that process I always get a pile of little shorthand sketches for ideas I think might be viable for multiples. Those get developed alongside the one-offs, with a lot of revisions and chats with my assistants about how to make the making of them go smoothly.

Julia Turner: There are some one-offs and some multiples, and for the first time some pieces which are in between. I’ve been slowly shifting my way of working to allow other people to be really involved in making the one-offs, rather than designing things only I could make, and this is the first time I feel like I really succeeded in doing that. The result is that I can work in a way that feels lighter, and play with variations without using all of the available time making just the framework for the piece. I’ve always produced new work really slowly and I’m excited about working in a way that’s more collaborative and expands what’s possible.

I understand that you just moved into a new studio space in San Francisco that is owned by the old California firm of Heath Ceramics. Can you tell us about the space and how you are using it?

Julia Turner: My studio is one of a handful of maker spaces that occupy a small part of the 60,000-square-foot factory that Heath leased about three years ago for a major expansion of their manufacturing. The gathering of other makers under their roof was a very conscious choice, and it’s evolving into a wonderful collective. They did a beautiful job of converting the building. The space we’re in is a simple open room with an old timber ceiling, big windows, and a wood floor that’s been thrashed enough that we don’t have to worry about messing it up. I share about 1300 square feet with my friend and colleague Liz Oppenheim, also a jeweler. We work really differently and the studio is loosely divided but there’s a lot of tool-borrowing going on. We have a miniature wood shop, soldering stations, polishers, computer desks, worktables, a display area, a sofa, a studio kitchen, and a big table for everyone to have lunch together. There’s no shower, or I’d be secretly living there!

Julia Turner: I have between three and five people coming in and out of the studio, doing different kinds of work at different levels, some here and some in their own studios, and a more extended circle of people for specific jobs outside the studio (like waterjet cutting, bigger woodworking, etc.) that are pretty central but that I don’t have the equipment for. I still do a little bit of everything, but am delegating more and more of the administrative work so that I can be working on new projects, including some new collaborations outside the studio. I seem to change direction a lot and so I don’t tend to bring people in to fill a specific job description—usually what happens is someone really great shows up somehow, and then we figure out how to work together. Everyone is really flexible; it’s occasionally confusing, but mostly great.

What have you seen, read, or heard lately that you loved?

Julia Turner: A friend recently brought me a book of Ellsworth Kelly’s drawings. It was in the middle of a really jammed week and I opened it and was struck by how raw and simple they were, how much in contrast to what was going on in my studio at the moment. I’m not actually sure I loved the drawings themselves, I just loved the feeling of, “Oh, right. That.”

Thank you.