Jessica Calderwood, a sculptor, image maker, and jeweler, uses the medium of enameling to explore issues of gender and identity, and to make statements about everyday life. Her pieces, meant to be both humorous and ironic, walk a fine line between beautiful and bizarre, encouraging us to reflect on our own emotions, relationships, and place in the world. Here Jessica talks about her work, flowers, and women’s role in society.

Bonnie Levine: How did you get interested in jewelry, and how did you get started?

Jessica Calderwood: I actually majored in “enameling” separate from metals for my BFA. At the time, the Cleveland Institute of Art was the only school in the US to offer that. I was a painter, initially, and I found enameling by chance and immediately fell in love with the process. At the time, I was most interested in making large-scale wall works and sculptural forms.

I only discovered jewelry, as an avenue in my work, much, much later when I took a workshop at Penland School of Crafts, where I was learning die forming from Keith Lewis. My fellow students said, “just try making one of these pieces wearable, just try it.” It was serious peer pressure. Since then, it has become a core part of my studio practice, where the jewelry becomes part of a dialogue with the larger-scale work. I enjoy the fact that my pieces are often about the body and then have a life on a body.

You’ve worked almost exclusively in enameling, which is a very ancient technique that’s been referred to as a “marginal craft form.” What’s inspired you to use this technique, and have you ever used other materials/techniques?

Jessica Calderwood: Enameling does something for me that paint does not. It has the ability to work on complex and dimensional forms; it can be fleshed out in large, industrial scale; or taken to micro-detail. I have been working in this medium for over 15 years and I’m still captivated by the process.

I call it a marginal craft because it is a beloved stepchild to metalworking. It can’t exist without metal, but metal can certainly live without enamel. Not many people outside of the craft world even know it exists. I have often been frustrated by that fact and that it is a medium heavily dominated by women. I have thought about the place of enamel a lot and often question my own use of the material. With this current body of work that involves gender and identity, it makes perfect sense to use enamel, and I see it as a lens through which to view the content in the work.

That discovery has opened me up to also explore other marginalized crafts in the series, including polymer clay, wool felting, and china painting.

Your work is all about women, gender, and identity, and explores themes of contemporary life: growth, metamorphosis, aging, and death. Tell us more about this. Why are there no men in your work?

Jessica Calderwood: Well, my work is very autobiographical and I am fed creatively by my own daily experiences, and I need to get that stuff out of me. I need to make sense of it. As I continue to grow, change, age, my view of the world and my identity changes. It’s messy, surreal and beautiful all at the same time. I’m trying to express that.

The most recent body of work being shown at Reinstein|Ross includes a number of pieces that represent women as well as men as a part of these stories and themes. It was important for me to incorporate both genders, to tell a larger story. Relationships are a huge part of my work so it seemed silly to not have both men and women involved.

When I look at your jewelry, it feels humorous, provocative, ironic, and yet enigmatic. Is that deliberate? What is it that you want the viewer to experience and take away?

Jessica Calderwood: Being a bit enigmatic is intentional. I don’t want the work to be totally unclear, but it’s important that the work is not a “one-liner,” that its message is revealed through multiple pieces and viewings.

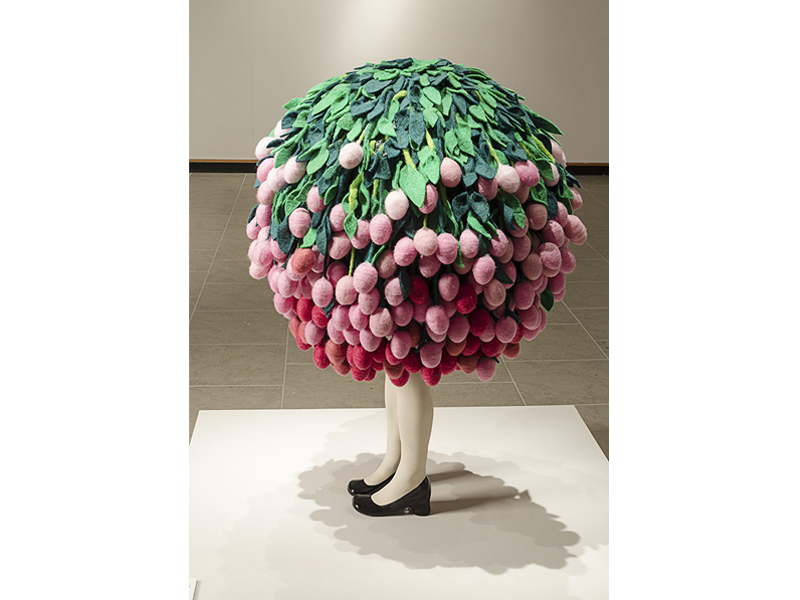

I think that women are in an unusual and interesting place right now, feeling both powerful and confined, simultaneously. The flowers, for all of their beauty, negate and censor the figure, the person. My work tries to express that dichotomy and frustration.

That idea of simultaneous opposites has also fed some of the formal decisions in the work. For example, the floral elements are always a series of organic elements that combine to create a distinctly geometric form.

Your most recent work combines flowers and botanical forms with parts of the human body to create what you call “anthropomorphic beings that are at once powerful and powerless, beautiful and absurd, inflated and amputated.” How do flowers and nature convey these feelings? Do you use specific flowers to signify certain emotions? What other signifiers of gender and societal norms have you explored in your work?

Jessica Calderwood: Well, this whole series started out by taking the phrase “as delicate as a flower” and expanding upon that in a funny, tongue-in-cheek manner. I already had a sketchbook full of watercolor studies of flowers from my travels, something I did for fun to pass the time. So, I decided to combine those with fragments of the female form, changing the type of flower to say different things, to create a personal narrative in the work. I developed a series of characters and researched the Victorian language of flowers as a way to provide direction and intentionality.

A previous series that I explored in jewelry examined hair, both as a signifier of gender, class, and age, but also as a beautiful sculptural form. There are definite parallels between this current body and my previous explorations.

What are your thoughts on the use of/role of color in your work? How does it shape the narrative?

Jessica Calderwood: I have always had a strong sense of color in my work—I love intense hues! I don’t use it illustratively, but emotively. I want the color to capture a mood in the work more than record something from real space.

Tell us about Flora and Flesh, the show currently on exhibit at Reinstein|Ross. What is your concept for the show, and how do the pieces you’re presenting illustrate that? Is this body of work new or different from your other bodies of work?

Jessica Calderwood: This current exhibition really brings together all of the ideas that I’ve been grappling with through a collections of brooches, enamel wall reliefs, and mixed-media sculptures. Although I’ve been working on this series for a number of years, this show is composed of largely new works that also include a masculine element. As I work through these ideas, I realized that the issues I’m talking about really have to do with our relationships to each other, men and women. I needed to address that.

The new works have also abandoned the specificity of the floral elements and have become these masses of colorful forms. This has been liberating and, for me, they become more about these looming clouds of color that block out the figure than a Victorian-style botanical.

You’re an instructor at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh. How has teaching influenced you as an artist, and how has your jewelry making influenced your teaching?

Jessica Calderwood: Teaching is one of the most challenging jobs I have ever had—it keeps me on my toes! What I love about teaching is the dialogue, the give and take—that I get just as much energy and information from my students as I hope they get from me. It has made me a better artist, by forcing me to expand my repertoire and to articulate my thoughts about art clearly.

Making jewelry has also taught me to be detailed, to really hone my craft. When something is only 50 mm tall, every surface and mark matters, is examined. Working from large scale to small scale has made me hyper-aware of that and the differences in process. Changing scales exercises different parts of your brain. I try to pass these sensibilities on to my students, for them to question why they work in a particular scale and how to consider construction approaches. I also stress the importance of craftsmanship, care for the process. I think I’ve been deemed the “craftsmanship police” at my school.

What have you read or seen lately that has made an impact on you that you’d like to share with readers?

Jessica Calderwood: I recently read So Sexy So Soon, by Diane E. Levin and Jean Kilbourne, about the early sexualization of our children, why it is happening, the repercussions, and how we can curb it. Kilbourne is a watchdog for society and gives lectures internationally about the power of the media to shape gender, identity, and unhealthy attitudes about the self. I saw her give a lecture at UW Oshkosh years ago that absolutely impacted my work and life. I think everyone would benefit from reading her work or attending a lecture—powerful arguments.

Thanks for the opportunity to let me explain myself!

Thank you very much.

Pieces in the show range in price from $360 to $8,990 for the large sculpture.