Jaydan Moore is quickly gaining recognition. His recent exhibition, Lost Causes, at Ornamentum Gallery, has further sparked interest in his young career. Lost Causes, which pairs Moore with accomplished British metalsmith David Clarke, presented the different creative outcomes of two artists working within similar materials, processes, and aesthetics. Moore’s transformative precision, applied to antique table service objects such as silver service platters, leads to beautifully austere sculptures. Touching on the human experience of everyday objects, his work is both aesthetically and conceptually rigorous. Currently completing a three-year residency at the Penland School of Crafts, he recently set some time aside to speak with us.

Ahna Adair: Your website bio states that you were born into a family of fourth-generation tombstone makers in Antioch, California. What was that like? And can you talk about how this has informed your perspective as a craftsperson/artist?

Jaydan Moore: Growing up in a family that made tombstones had a profound effect on me. Most of my time after school was spent taking rubbings of the tombstones or listening to families make arrangements for their loved ones. As a child, I found it so interesting that we create a place and statue to best represent a person.

Behind my family’s storefront, we also owned a storage facility where many of our clients kept their belongings. I spent a lot of time rummaging through these units, looking at what types of things people held on to. Looking at these two different types of objects, the tombstones and the keepsakes, made me begin to feel that the things in the storage units had so much more meaning than the information written on each grave marker.

From your beginnings in Antioch, how did you find your way to metalsmithing?

Jaydan Moore: When I was still in high school, I was given the opportunity to attend the pre-college program at the California College of the Arts, where I took my first metals class. The ability to manipulate easily what seemed like such a rigid material opened a tremendous amount of possibilities, and I immediately felt a connection. It was the first time I found a material, techniques, and tools that I wanted to work with nonstop.

Ends, from 2012, stands out to me because it takes on a subtle jewelry-like presence. Were you always firm in your resolve to identify as more of a metalsmith than a jeweler?

Jaydan Moore: The potency and personal connection of jewelry to the body has always excited me, but I am more intrigued by creating an entirely new space for my objects to live within. I believe my works still have a relation to the body because they retain details that suggest how the objects were once used. For instance, the sculpture Platter/Gather is so large and appears to be in such a state of decay that it seems impossible to actually carry, but the handles are still there to make it conceivable. I enjoy the scale of these objects and the notion that they can live within two worlds, one connected to the body and one connected to a commemorated past.

The piece Ends was a way to convey a timeline of my work with this material. Taking the leftover decorative rims, I made a single continuous loop, like an old rope, and hung it on the wall. It wasn’t until the piece was finished that the object began to resemble a large necklace.

Your work at the moment requires a rather large accumulation of similar objects, secondhand tableware. I’m thinking of a piece like Platter/Gather. What does sourcing materials look like for you? Is it an endeavor that you like to take upon yourself, or do you have people helping you sift through thrift shops and estate sales?

Jaydan Moore: When I first started working with silver-plated platters, I spent a lot of time going out to secondhand shops and antique stores. I found it helpful to be able to handle each object. Now eBay has become the best way for me to source my materials. Each time I need new objects, I can search through around 2,500 articles online and have them sent directly to me.

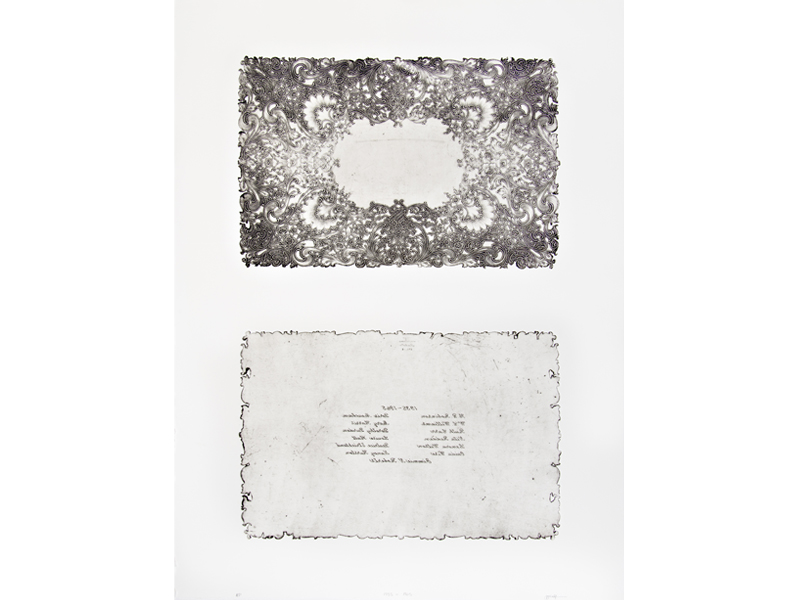

After leaving graduate school I also started looking for ways to connect with the previous owners of these wares in a personal way. During my residencies, I have been doing a donation project for silver-plated platters. If anyone is willing to donate their heirlooms, I will then print a single edition for the owner as a thank you. I have received dozens of donations, and instead of gathering all of my materials online, I am able to have a discussion with the owner, hearing how individual plates came into their possession.

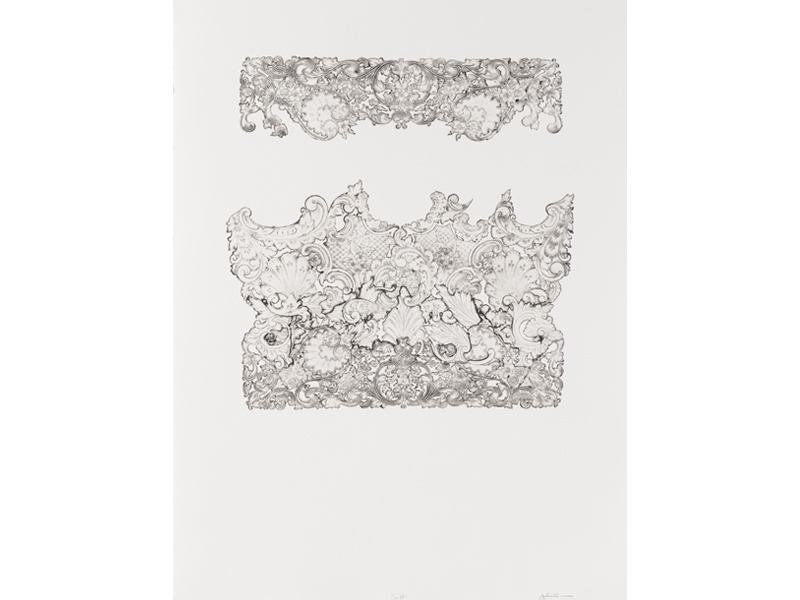

You are a wizard with the jeweler’s saw. In addition to meticulously sawing along the decorative floral patterning etched into the platters, you also practice a hard line splicing to puzzle the platters together. Is this a conceptual choice, a practical choice, or a bit of both?

Jaydan Moore: I began working with these platters by cutting them in shards to then reassemble into a larger object. As I kept working, I wanted to show how similar the decorative patterning on each platter was. By highlighting these shared details, I hope to extend the comparison to the objects’ owners, pointing to their own similarities. I also hope to discuss the communal nature of these objects and how each owner has an effect on the societal significance of service ware.

These pieces are put together with low-temperature solder, also known as plumbers’ solder. I do this for a few reasons: First, the existing patina will burn off if I take it to the temperature that is needed for high-temperature solder; second, the silver plating will begin to bubble and burn off. Third, the decorative edge on these platters is made of pot metal, which melts at around 400 to 500 degrees. By marrying the patterns versus sawing the platters into shards, I can strengthen the low-temperature seams by creating more edge area. The larger platters like Platter/Gather have a lot of flex from the amount of surface area, and the meandering seam helps deflect stress and avoid seam splitting.

It’s been four years since you completed your MFA and MA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since then, you have completed a residency at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, a fellowship at Virginia Commonwealth University, and you’re currently in residency at the Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina. What do you enjoy about the residency experience, and how do residencies differ from other working environments you have experienced?

Jaydan Moore: In addition to providing me with a work space, residencies have been a great way to meet new people and learn new things from the society that gravitates around these amazing universities and craft centers.

At the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, I had discussions with the public on open-studio days about what I was trying to do with my work. This helped me find the right terminology and comfort with the concepts I wanted to discuss.

Virginia Commonwealth University provided me with the right tools and equipment to explore new techniques in my work. Along with this, I was able to dedicate time to being a teacher and connecting with new makers, and have amazing discussions on what they are thinking about, and what ideas have defined them.

Finally, here at Penland I have been able to fully immerse myself in my studio and to delve deeply into a full-time artistic practice. Penland also gives me space to learn the business side of this practice: What does it take to make sure everything gets out on time? If you are going to make larger work, how do you ship it? It has also made me think about how I could give back to the community, alongside teaching.

Glenn Adamson wrote the intro for your current show at Ornamentum, which paired you with a key figure in British metalsmithing, David Clarke. The placement of your work side by side is creating a bit of a conversation. In his remarks, Adamson addresses a common reaction of those within our field, who opt for criticism when similarities between artists are perceived. Unlike in the fine arts world, we have a difficult time recognizing originality despite similarity. What’s your take on this?

Jaydan Moore: I have been thinking a lot about this question since Glenn Adamson’s article came out. I agree that this is a major challenge with making art and being a part of any field in general. How do you make the work you want to make while not encroaching on another person’s visions? I do agree that there are similarities between David’s work and my own, between the materials and the way we engage with memories’ fleeting power. I am very lucky to be in the same conversation as David, and I do believe that Glenn Adamson was able to parse out how differently we bestow memories to objects. A great number of artists have chosen to work with found materials and discuss the history of silver in our society. I feel each addition to the conversation adds to the dialogue and strengthens individual idiosyncrasies.

Your prints feel like visual obituaries of the heirlooms you choose to work with. It crossed my mind that this is a nice parallel to your experiences growing up. What is the conceptual relationship for you between the prints and the sculptures?

Jaydan Moore: While working on the platters, I became interested in finding a way to represent the unique markings made by their previous owners. I began searching for platters that had been scratched multiple times with some sort of utensil. Looking at these objects, one is able to gain an impression of how they were used. What I found most perplexing was how something this used falls out of relevancy. I wanted to capture this change in importance in one final image. Like recollecting a memory for the last time. With this in mind, I cut out the plate’s bottom, inked the plate like you would an etching, and printed it onto paper. In doing this, the tray is destroyed, never to be used again. What I hope is that the prints are brief documentations or states of this history being lost.

This body of work, while showcasing your technical precision, has a very poetic ebb and flow. The objects you are transforming are replicas of 18th-century originals. Deciding to use them as art materials and implementing metalsmithing techniques points back to a time when artisans were hand-producing these platters. Along with the personal stories of the people who owned the more modern replicas, I also see a narrative about skilled artisans of the past. Is it your aim to connect yourself to that past in a way that is relevant today?

Jaydan Moore: This great question gets me back to exactly what drew me to these objects. Made on a mass-produced scale, these platters allude to the hand-crafted sterling silver platters, teapots, and silverware that we now find on display in museums. Adding just the thinnest layer of silver onto copper, brass, steel, and pot metal will add the many supposed connotations of value inherent in silver. These objects show how important those hand-made objects were to us, and what I find so interesting about them is that their image has retained their importance for society, despite the fact that we have no use for them, except as memory of what once was.

It is this showing of use that I find the most exciting. I had spent much of my career trying to create things that looked old but were just forgeries of old age. I came to a point where I wasn’t interested in buying a new sheet of metal and evoking signs of history. Using these objects, I am able to build a history with many timelines.

You are in your final year of a three-year residency at Penland. Can you tell us what your current experiments and interests are, and where you expect these will take you?

Jaydan Moore: During this residency, I have spent a lot of time experimenting with different print processes. I have been finding new ways to alter the plate through drypoint work, aquatinting (a lighter version of etching), and engraving. I have been using these techniques to create many different states of the same plate.

This experimentation has translated into finding new ways to alter these metal objects in my own studio. I have found that the silver plating on these objects is much more resilient than I once thought. With this new knowledge, I have begun forming and high-temperature soldering objects together, altering each form and adding elaborate decorations that flow within multiple found pieces. The embellishments, alterations, and deconstructions all define the piece and reflect, in my eye, how society defines itself through the many alterations of individual objects. Finally, since the prints and the sculptures are both made from the same material, I am working on pairing them together to create a surrounding for each.

I just read an American Craft Council interview with you from last year. In response to a question about how your career has gone thus far, you said, “I had a very focused plan of how my career would go. That has not been how my career has gone at all, but all for the better.” I really enjoy reading about your success. And your comment piques my curiosity. What was the original plan?

Jaydan Moore: When I was completing my undergraduate degree, my plan was to head to graduate school and work as hard as I could and then find a teaching job directly after that. This is a great trajectory, but if I had pursued it, I think it would have been detrimental to my career as well as a challenge to my students. As I got further along in my graduate studies, I began to see a multitude of different paths ahead. I had the tremendous opportunity to go to a few residencies and learn to be a better artist and teacher before making a final decision of how my career should unfold.

Are you reading anything that’s helping inform the work you’re doing at Penland?

Jaydan Moore: I have started a couple new books this summer to begin thinking about new directions on how individual and communal ideas on memory, commemoration, and nostalgia affect one another. I’ve been reading The Tears of Things, by Peter Schwenger. I have also started reading a few chapters of The Future of Nostalgia, by Svetlana Boym, and Memory: Histories, Theories, Debates, edited by Susannah Radstone and Bill Schwarz. When I’ve needed to get away from that type of specific reading, I’ve turned to The Story of My Teeth, by Valeria Luiselli; Ficciones, by Jorge Luis Borges; and One More Thing, by B.J. Novak.

Whose work do you admire, both in the field of jewelry and more broadly, and why?

Jaydan Moore: Myra Mimlitsch-Gray has an innate ability to form metal into amazing objects, and she finishes each object so flawlessly that they turn into perfect masses that could be hollow or solid. Cornelia Parker’s work with silver has also been a major influence: Both her tarnish drawings and crushed platters discuss the nature of metal’s materiality eloquently and simply. El Anatsui’s large tapestry pieces have also intrigued me, in how he has taken simple pieces of trash and turned them into these beautiful color palettes. Finally, Richard Serra’s large installations let you immerse yourself in a field of rusted steel.

Outside of metal, I truly love William Kentridge’s animated drawings. David Maisel’s Library of Dust photo series has also been a haunting image of an object being lost. All of the photos are of cremation canisters forgotten in a mental institution. As the chemical compositions of each person react with the canister, it begins to create different striations and growths that are individual to each. Judith Scott’s string-wrapped forms, mixed with all kinds of found objects as armatures, are truly extraordinary.

The pieces in this exhibition range in price from $2000 to $60000.

INDEX IMAGE: Jaydan Moore, Utensils, 2015, sculpture, found silver-plated spoons, 16 x 26 x 3 cm, photo: Mercedes Jelinek