The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is one of the world’s great museums. Alongside encyclopedic holdings of the evidence of human creativity from around the globe, contemporary jewelry has found its place in the collections under the watchful eye of curator Jane Adlin. In 2014, the Met will present an exhibition and publication about the collection of American Donna Schneier, whose donations to the museum form the core of its growing collection of studio jewelry. In 2013, I had the chance to speak with Adlin about her role, the contemporary jewelry collection, and her plans for jewelry in the future.

Damian Skinner: Tell me about yourself and your role at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jane Adlin: I am an associate curator in the department of modern and contemporary art. It is a great department, because it deals with such a broad sphere of culture. My role is specifically concerned with the collection of design and architecture.

So there’s not a separate decorative arts section in the museum?

Jane Adlin: That’s correct. There is a European sculpture and decorative arts department that collects and exhibits Renaissance works to 1900. Also, there is an American wing with two separate departments: American paintings and sculpture and American decorative arts. I am part of the larger area of modern and contemporary art, and mostly that’s to my benefit because I can include paintings and drawings and sculpture into the exhibitions I curate if I so desire. The chairperson of our department, Sheena Wagstaff, is extremely supportive.

Jane Adlin: The American decorative arts collection goes up to World War I, so if you consider that contemporary, then yes, there’s someone else that does what I do. That department deals with American jewelry up to 1917. I deal with international objects, starting in 1900 through the present.

Including America?

Jane Adlin: Yes, except for American applied arts between 1900 and 1917.

Tell me about your own interest in contemporary jewelry.

Jane Adlin: When I came to the museum, the mandate was to get the collection on view. My first job was to go through the files and look to see what was in the collection. We were very strong in art deco design, the post World War II craft movement, and in some other areas. We were not very strong in jewelry, although we had a couple of key pieces. I love jewelry, so it was easy for me to say, “Well, let’s see what we can do about strengthening that part of the collection.”

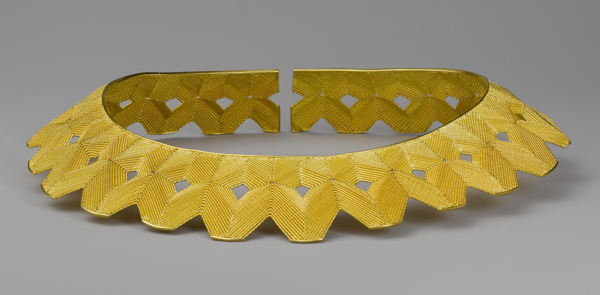

Jane Adlin: I look at contemporary jewelry as part of contemporary design. I don’t like to categorize things as craft or art. I’m always looking at a wide variety of objects. A key figure in relation to contemporary jewelry is Donna Schneier, who I’ve known for years and who has always been very helpful to me in all kinds of ways. We talked about what she was going to do with her jewelry collection, and she decided to donate it to the Met. That was just brilliant. I’m thrilled to have it, and we’re building on her collection, making it even more comprehensive. This is an ongoing collection, which is an excellent situation for me because I get to have a colleague—or a fairy godmother! As a curator, part of my job is to consider the collection and see what I’m missing, and she’s listening to what I think I’m missing and helping me address those gaps.

So, the relationship is very active.

Jane Adlin: Yes, and here’s an example of how it works. Donna Schneier was in Munich in 2011 for the yearly international contemporary jewelry fair. I was unable to go. When she got back, she said, “I can’t wait to show you what I’ve purchased.” In 2012, we went together to Munich, which was amazing and energizing.

When did Donna Schneier’s collection come into the museum?

Jane Adlin: We accepted it at the end of 2007, but before that there was a period of research, negotiations, and paperwork. This is a big institution, and there were a great many approvals, show and tell sessions, and time spent talking to people, such as Philippe de Montebello, the director at the time, and educating him and others about contemporary jewelry and why we should collect it.

Did you encounter any resistance?

Jane Adlin: A little bit. Not a lot. The resistance was mainly about the size of the collection and how we would responsibly care for it and show it, because we don’t have a lot of exhibition space. And as a curator, I am not dedicated only to contemporary jewelry. I work on historical and contemporary exhibitions and cover the whole range of design in the twentieth century. The questions from the institution were: Why did I want her entire collection? Wouldn’t it be better to take a few pieces rather than all of them? The Met has been offered whole collections before, which we’ve turned down. In the end, we didn’t take the whole collection. Donna was remarkable. She said, “Take what you want.” I took 109 pieces. She had many more, and in fact, the collection has now grown to 123 pieces with subsequent donations. But in the context of this museum, to take so many works from one person’s collection was an achievement. This reflects the exceptional nature of Donna’s eye.

Jane Adlin: The show is scheduled for summer 2014. It will be in the modern and contemporary design gallery. The publication features an essay by Suzanne Ramljak and many full-color illustrations of works from the collection.

Does the museum have other examples of contemporary jewelry that have not come into the collection via Donna Schneier?

Jane Adlin: Yes. There are perhaps 40 or 50 pieces. We have some great Alexander Calder pieces. I have a donor who’s very interested in midcentury modernist jewelry, and she’s been buying works to donate to the museum. I’ve also been working on building up the already strong collection of art deco jewelry.

What are your ambitions in terms of representing the field of contemporary jewelry in the Met?

Jane Adlin: Basically, what I want are the key artists, and I want the best work of those artists. I’m interested in telling the story of jewelry from the beginning of the twentieth century, and because I’m open-ended, I can’t predict where the collection will end … well, it certainly won’t end with me. I’m always looking for the perfect piece to fill in a gap in the collection. The Met doesn’t intend to aggressively collect young unknown jewelers, which is not to say that we haven’t collected some of this work, but it is not a key objective. I will say I went out on a limb with some of Donna’s pieces, and I accepted a few examples of experimental work. We’ll see how it goes, but it’s here now and it will be in the show. I think most collectors would understand the museum’s position. If you want to see the most outrageous jewelry, you go to a dealer or to a contemporary art fair.

What kind of budget do you have to acquire contemporary jewelry?

Jane Adlin: The department has some funding, but a lot of the funds are restricted. I have a couple of very small decorative arts or design funds that are dedicated to objects, but they don’t enable us to acquire many objects. On occasion we do purchase, but the funds are minimal, and again, it’s spread between all of the various media that I am responsible for. For example, I have one fund that’s restricted to pre-1940s design and another fund that is restricted to design between World War I and World War II. As a result, my first line of defense is to approach interested purchasers who will buy on the museum’s behalf or to collectors who want to give. If that doesn’t work, I try to raise the funds in some other way. It’s a little complicated, but I have really dedicated collectors, people who do like being part of the Met’s family and helping develop the collection.

So, you are interested in hearing from collectors who may want to get involved?

Jane Adlin: Yes, definitely.

How do you get an exhibition accepted into the program?

Jane Adlin: It’s relatively straightforward. You propose it to the department chair, and then it goes to the director. If you have a good idea and you present it well, it’s feasible. I have had a lot of positive response within the museum to exhibition proposals about design. One of my first shows, and a real highlight, was the exhibition of Scottish designer Charles Rennie MacIntosh. Then, there was the Cartier jewelry exhibition and an exhibition of British ceramists Lucie Rie and Hans Coper, which was a rare presentation of their work in the United States. Currently, I am working on an exhibition of JAR Jewelry, which is one-of-a-kind jewelry, and of course, the Schneier show.

Do you find design a useful term for thinking about the kind of objects that you cover?

Jane Adlin: Not particularly. I inherited that name. The formal title is the “Collection of Design and Architecture.” There are many names for the kinds of objects I work with. I don’t have a problem with decorative arts. I don’t have a problem with crafts. I don’t have a name problem, so I say design. When contemporary jewelry enters this museum, it becomes part of the Collection of Design and Architecture within the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art. Whatever the audience calls it is fine with me. I just want to make sure that we educate and inspire with the objects we collect, protect, and show.

Thank you.