Amina Rizwan: The AJF Award is so transformative for contemporary jewelers because of its most significant aspect: The work and its maker acquire a new visibility. What changed for you and your practice with the visibility of the award?

Bifei Cao: As one of the prestigious contemporary jewelry awards, the AJF award benefited me and definitely exposed my work to a more international platform. Except for purchasing some tools, I spent most of the award money traveling to different international events, such as Schmuck 2018, a SNAG Conference, SOFA Chicago, and Radiant Pavilion, continually involving myself in art and cultural events in different countries.

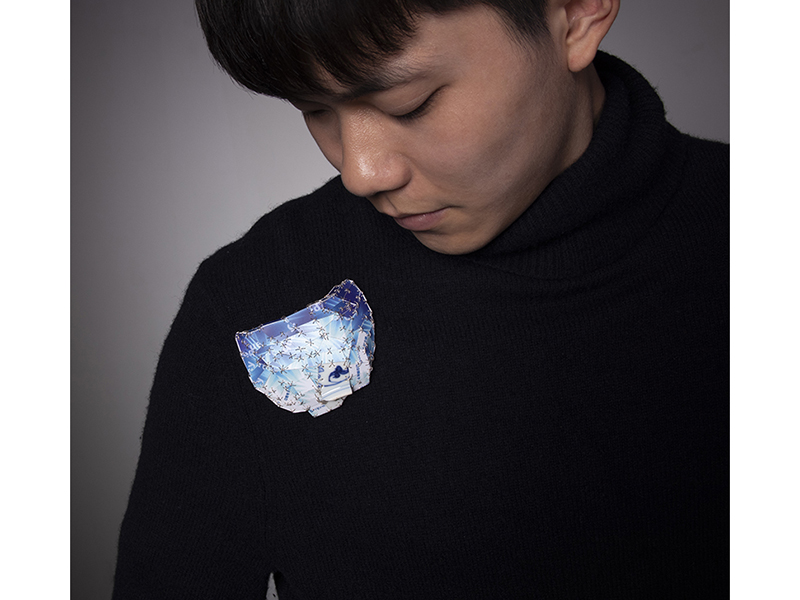

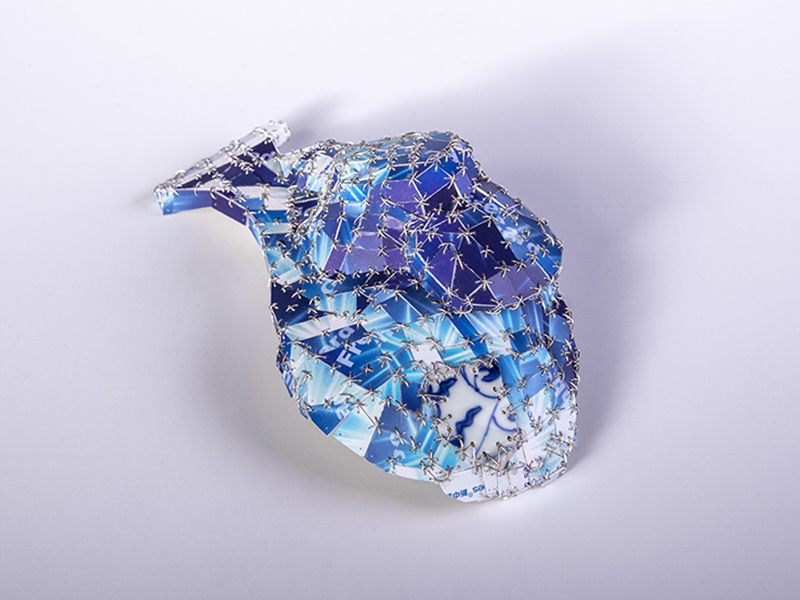

The visibility of the award hasn’t changed my practice. I have been consistently using a similar method to explore different possibilities. The investigation includes material experiments where I face recycled materials, such as invalid credit cards and cafeteria food cards.

The only change is in my personal environment. After 10 years of living and studying abroad, I had to readapt my life to China. After beginning to teach at the School of Art and Design, Guangdong University of Technology, in Guangzhou, I joked that I hit an “unbreakable spell”—that of the Chinese maker who returns to China but is unable to produce more works compared to his production overseas. Almost all of us who return to China teach in different universities and have to adapt to the one-size-fits-all research evaluation system that Chinese universities use in every academic domain: arts, humanities, and sciences. The majority of makers who work in academia depend on publishing papers in SCI, SSCI, and A&HCI (the Science Citation Index, Science Citation Index, and Arts & Humanities Citation Index) rather than on personal works and exhibitions. It has been one of the weirdest judgments for me as I’ve lived in China the last two years, and I hope it will change soon.

In your last AJF interview, you spoke about returning to Yunnan province for further research into traditional Chinese crafts and their embedded historical and cultural meanings. What materials, processes, or traditions have you connected with this time?

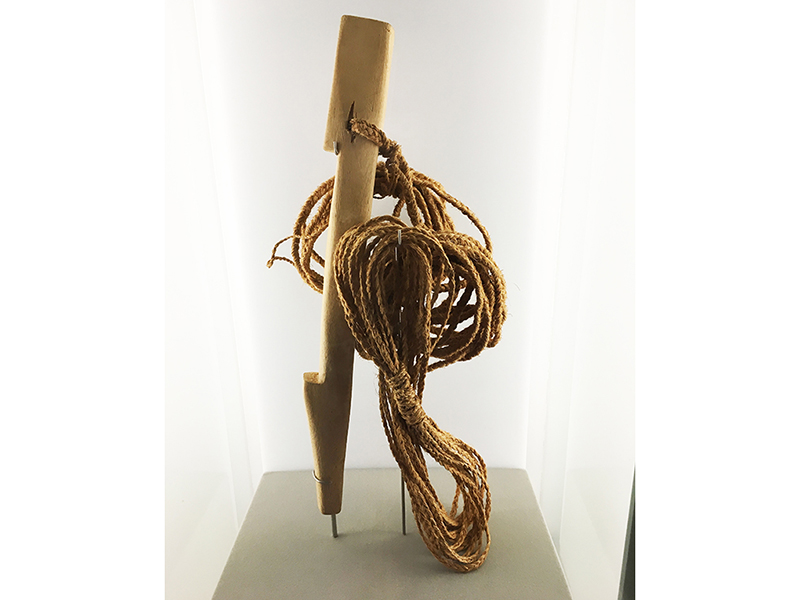

Bifei Cao: Yes, I traveled to the Bai nationality area in Yunnan province, where I researched traditional Bai raising technique and related blacksmithing techniques. However, the most unexpected experience was an encounter there with traditionally knotted objects in the Yunnan Nationalities Museum, in Kunming. Later on, I was reviewing traditional Maori knotted objects at the Te Papa (Museum of New Zealand) during a residency program. Both observations allowed me to capture this primitive and original making method unconsciously. I continue to apply the historic joining method that was used for a jade burial suit made during the Han Dynasty in China, imitating each traditional knot.

Besides that, I spent most of my spare time writing a book, titled Casting in the “Threshold”—Chinese Contemporary Jewelry (1990–2020), which the American company Schiffer will publish in 2020. It introduces the general development of Chinese contemporary jewelry in the last 30 years with a collection of 62 Chinese contemporary artists. The writing has been an extension for me to understand materials, processes, and traditions after receiving the award.

What do you teach? As a cross-cultural artist with anthropological affinities and investigations into Chinese traditions, materials, and crafts, what does it mean for you to teach?

I currently work as an associate professor in the School of Art and Design, Guangdong University of Technology, teaching courses such as Foundation, Material Design, Craft Thinking, and Jewelry Design. Among these classes, I’ve brought an international craft environment to my students, a broadened review of different situations in contemporary crafts and arts, a range of artists and their works, and theories from art historians and art theorists. I’ve shared my making experience as an example of research in reinterpreting traditional crafts, material, and related culture and philosophies. It has really been about sharing my practice rather than imposing my idea on students.

As a juror for the upcoming AJF award, what are you looking for beyond originality, concept, or craftsmanship?

Clear ideas with clear expression. It has been an important consideration in my personal making. According to my superficial review of the field, my first impression is a large number of art jewelry works with infinite stacking of materials and colors. I don’t mean these works are bad, but I wish I could read, understand, and interact with these pieces. No matter how they investigate either or combination of technique, material, and form, or explore the functionality of jewelry to be wearable or adored, have symbolic meanings or challenging idea and concept, I would like to see works that have dug into any of above concepts deeply and clearly.

You operate from the position of skill (and historical implications, too). Is it one of your aesthetic devices when looking at or judging works?

I definitely won’t look at any works based on my idea of my own creations. It’s only one of the devices or methods for artistic making. It will nonetheless be great to see the kind of works that reinterpret tradition through contemporary expressions, if any applicants have a different way of reinterpreting their traditions.

Let’s talk about your work. You say, “Each work deploys a dissolving and reshaping position to reflect on the temporality of our cultural situation.” Your work is intellectual and intriguing on many levels. It has a diasporic quality. Shifting. Reshaping. Dissolving. But what it reminds me of is the word continual: continual as both a process in one’s search for identity, but it also becomes the material and process of making itself. Is continuity an important material and thought in your work?

Continuity has been one of key characteristics in my work. I define myself as a craft-based maker or artist who originally trained as a metalsmith. My early metalsmith training formed a good skilled foundation for me and allowed me to think through different concepts continually. This consistence benefited my current cross-disciplinary research between humanity and craft. My exploration has been a continuity of reinterpreting tradition, a consideration of continuity (temporariness) in cultural identity and keeping searching the process of making. Key words such as “connect,” “insert,” and “attach” express continuity in my works. I don’t know what exactly is next for my work, but emphasize these key words in my artistic exploration.

Your Vase series references traditional objects used in China. How do you view their functionality or historical connotations in a contemporary context? How does subverting and removing their own originality create a new emotional space, concept of function, or a new skin of the vase?

Traditional Chinese vases and pottery are daily-use objects, fragile and replaceable, developed through ancient Chinese history. Different Chinese artists reinterpret their functionality and historical connotations to create contemporary art. Work such as Ai Weiwei’s Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995) pushed me to wonder if he tries to unburden his traditional Chinese cultural influence. As a member of the generation born in the 1980s, after the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), I disconnected with a lot of tradition and traditional objects. Like shattered traditional porcelains or vessels, linking these broken parts to imitate traditional forms or reconstruct into new forms became my intention to make connection with tradition. While using traditional techniques to comment on contemporary life, could my work be contemporary, or the contemporary context imbued with historical connotations? I had all these thoughts when I was making. I also cared about how to reconstruct tradition in a contemporary way of subverting and removing their own originality rather than mimicking tradition.

With these considerations, bringing contemporary life experience or feelings to my work has been another level of construction, where I engaged with thoughts of cultural identity that were related to my personal experience of more than 10 years spent living overseas, especially the multicultural and influences of place. Each new emotional space, whether enclosed or opened, hosted personal memories of culture, history, and life experience and brought new functionality while combining traditional techniques with contemporary materials.

Where is your studio? What kind of visual library of materials, objects, readings, or sketches would we encounter there? Do you work outside the studio as well, for example engaging directly with the village or community of makers? Can you talk about your working process?

I have a public space in the graduate student studio in the School of Art and Design, Guangdong University of Technology, where I teach. I’ve hardly focused on making since I traveled back and forth between the US and China after leaving Australia in 2017. In my workspace, I can’t solder and explore materials. I have only a workbench with some drawings, sketches, bench tools, and samples. I have benefited from the residency program in New Zealand. A short three months gave me a great opportunity to experience Maori culture, communicate with various artists, and think about what’s next.

I guess my working process has been a process of craft thinking. My working process is a slow reaction. Every series of my work has depended on slow processes of sample making. During the working process, I find the closest way to express my idea, no matter how many attempts.

Are there any experiences in the contemporary jewelry field or beyond that have impacted or stayed with you?

I’m a person who keeps learning from different experiences and sharing my experiences in the field. I may be critical sometimes, too. My interest is in really enjoying a different place and cultural environment, learning to adapt to it; later, it becomes part of the experience of my life. I’ve been to so many wonderful cities: New York City, San Francisco, London, Amsterdam, and Melbourne. I feel Wellington is the best place to create a cultural harmony, as British or English-based culture and Maori culture have kept a great balance in Wellington, alongside other immigrant cultures such as those from India, Malaysia, and China. I experienced an amazing Maori welcoming ceremony, sharing air or breath through nose touching nose and singing Maori welcoming song together. These different local customs remain in my memories, allowing me to be open, understanding and embracing the world.

2020年国际艺术首饰论坛青年艺术家申请已经开始,针对全世界青年首饰艺术家,最终大奖奖金7500美金,截止日期2020年1月12日。三位著名的评审人分别是Jorunn Veiteberg、Barbara Paris Gifford和2018年艺术家奖得主曹毕飞(今年为了区分国际艺术首饰论坛的另一奖项职业中年资助奖,此奖改名成青年艺术家奖)。在这里,我们来采访这位中国艺术家,了解他自获奖以来的生活轨迹,也了解他在评审此奖时的关注点有哪些。

Amina Rizwan: 对当代首饰艺术家来说,AJF奖给予最大革新的重要点就是:无论是入选者还是最终大奖得主,人和作品都获得新的知名度。随着此奖的曝光率,你自己及你的创作方面有任何变化吗?

作为当代首饰至关重要的奖项,国际艺术首饰论坛艺术家奖为我带来很多。首先为我带来一个更大的展示舞台。除了购买了一些工具,我自己主要用于不同国家的旅行,给自己更多的机会走出去,比如德国慕尼黑国际首饰周、北美金工协会年度会议、SOFA芝加哥和墨尔本国际首饰周等,可以看到不同国际首饰周和艺廊作品展,体会不同国家的文化艺术。

我将获奖当做一个里程碑,对自己过去几年创作的思考与总结,并没有影响到我的个人创作实践,可能和我个人工作很慢、创作过程也很慢相关。作品不多,还是沿着相同的创作手法继续挖掘可能性,包括材料探索,尤其在中国目睹很多的垃圾材料,比如学校的食堂饭卡与银行失效的信用卡等,我也尝试延伸创作一些作品。

主要改变的是个人生活环境。历经10年的海外学习与居住,重新回到自己的祖国确有些不适应,也在花费时间来调整。任职广东工业大学艺术与设计学院以来,自己也常调侃自己,脱不开中国创作者的“固定魔咒”:一旦归国,作品骤减。重要原因之一是大多回国或中国自身培养的艺术家都在院校教学,中国手工艺教育的特点理论当家、实践为辅;大部分大学的科研考核指标是通过论文和项目来评定,针对任何学科诸如人文社科、艺术等都是采用一刀切模式,大部分艺术类老师没有依据创作作品与个人展览来评定科研成果,大部分艺术类教师也不再艺术创作与实践。自己也开始知道什么是SCI、SSCI和A&HCI,是近两年来我所体会最让人不可思议的评断准则,期颐在有生之年能够看到改变。

在上一次AJF采访中,你谈及进一步去云南研究中国少数民族传统技艺和相关历史文化含义。你现在的创作中,如何对接材料、工艺或传统?

是的,我尝试去过那边,分别调研过云南传统白族银器、铁器等手工艺。倒是有心栽花花不开,无心插柳柳成荫,我对昆明云南民族博物馆关注到传统少数民族的结艺,感触颇多。之后在亚洲新西兰艺术基金3个月的居住期间,新西兰博物馆毛利民族原始的打结也深深吸引我,让我不自觉去调研这最朴实的手法,通过诠释金缕玉衣的手法来再创作简单的打结,力争作品表达简洁而又清晰。

这一年,我花费太多的时间在全英文撰写书籍《中国当代首饰》一书,将于明年在美国权威手工艺出版社Schiffer Publishing出版。这本书时间太短,从一个创作者的角度对中国当代首饰的发展和现状做了简要介绍和分析,并囊括六十多位中国当代首饰创作者的简历和作品介绍。我并没有对很多当代首饰现象做深入探讨与分析。这本书也是让我在这段时间更好地去了解中国当代首饰中的材料、过程和传统。

你教授什么?作为一个跨文化的艺术家,与人类学有密切关系,并且不断调研中国传统,材料和工艺;教授这些对你来说意味着什么?

我目前任职中国广东省广东工业大学艺术与设计学院副教授,主要教授手工艺基础、材料与设计、首饰与金属工坊、服装设计的学生毕业设计等课程。在这些课程中,我更多的是分享国际环境下的当代首饰状态、不同艺术家与设计师作品以及不同理论的探讨。将我对传统文化、材料和工艺的理解当成一个案例讲给学生听,而不是强加我的个人想法。

作为AJF大奖的评审人之一,除了创意、概念或工艺之外,你还期待什么?

清晰的表达很重要。我目前对当代首饰最大的感受就是材料的无限堆砌与色彩的缤纷斑斓,但是不清楚作者具体表达什么,也不知道如何与作品互动。我比较浅知,并不是说这些作品不好。如果能在工艺、材料或造型,或者从功用诸如佩戴、装饰或意义上挖掘任何至极致,这是让我觉得是非常清晰的作品。这也是我这些年与接下去不断探索的方向。我很遗憾我也在探索,真心希望新来的申请者的作品都超越我。

你擅长从技艺的角度来进行创作(也包括历史性含义影响)。这个角度是你的一个评审作品的审美评定之一吗?

我个人绝不会基于我创作方法来评审作品。艺术家的创作方法太多元化,我的只是其中一种。但是我也是非常愿意看到这类作品,如何通过当代表达来诠释各国的传统。

我们来谈谈你的作品。你阐述“每一件作品呈现出融化、重塑的过程,反映我们文化状态的临时性。”你的作品在许多层面上都是思想性的、耐人寻味的,有一种不稳定的特质,变化、重塑、互融。但是你的作品也让我想起“持续”这个词:持续既是一个人寻找身份的过程,同时也成为材料和过程自我创造的持续性。持续性是你作品中重要的素材和思想吗?

非常感谢提及这一段。延续性是我这些年作品的一个重要特征,从早期金工工艺的训练与扎实,打下坚持的工艺基础,也造就自己是一个手工艺基础的创作者。基于这些训练才有现在的持续性:一是对传统不断诠释的持续性;二是个人文化身份的临时性,也是持续性;三是思考的过程也是不断持续的。

因为持续,我的作品也是采用连接、穿插、固定等有关联系关键词。尽管接下来我的作品具体走向不清晰,但是我会尝试在作品中不断加强这些点。

你的作品《瓶》系列源自中国传统器物。你如何看待这些作品在当代语境中的功能或历史内涵?如何颠覆和消除这些传统的原初性创作出新的情感空间、功能概念和瓶上的新“肤色”?

于我来说,中国瓷瓶或陶瓷器皿是中国人日常用品,是易碎和更换的,伴随着中国的历史发展而演变。无论在型体上的再构还是历史含义的再诠释,很多中国艺术家都在借助传统器物来表达,比如艾未未的作品《失手》(1995)砸碎传统陶器,让我会思索是否是卸下传统艺术与文化包袱?对出身于文化大革命后的80后一代,我们失去很多传统文化,像破碎的陶瓷片一样,如何重组,是否是我对传统文化的再诠释呢?传统陶瓷只是我的一个文化载体,我更多在乎在当代生活中怎样构建。

文化身份认同也是一样,我们都不可避免地受世界各地的文化、地域影响,如何融合不同的文化与感受带来新的诠释,正是我探讨与感悟的。用传统的技艺结合当代的材料不断连接有关文化、历史、个人记忆等碎片,形成新的情感与功用。

你目前的工作室在哪里?如果我们拜访,在你的工作室会看到什么样的材料、物体、书籍资料或草图等视觉空间库?你是否也在工作室外进行创作实践,例如直接与村庄或社区的手艺人沟通?你能谈谈你的工作流程吗?

很遗憾我还没有建立个人工作室,只是在广东工业大学艺术与设计学院里与研究生共享,容纳一张工作台,让自己不断进行创作。自2017年初从澳大利亚博士毕业后开始奔波于美国和中国,自己发现很难集中时间进行创作,相关的材料探索更加没有,只有一些图片、草图和部分未完成的样品。我很幸运受亚洲新西兰艺术基金的邀请,在新西兰创意学院进行了为期近3个月的居住创作,让我有机会感受毛利民族文化,以及和很多不同艺术家进行交流,受益颇多。

我认为我的创作过程是一个手工艺思考开始的过程,这个过程很缓慢,倒不是与我的性格相关,可能不太自信或太笨的过程,我需要自己用时间来确定。在创作过程中,我自然会尝试不同表达方式,找到接近与清晰的哪一个,所以我的每一个系列作品都建立在很多次的尝试。

有没有在当代首饰领域或其他领域的经验影响着你,或者留在你的记忆里?

我自认是一个喜欢学习不同经历,也愿意分享自己经历的人,尽管有时候也是很挑剔。我对不同地域、文化着迷,让我尝试去感受不同、模仿和成为我经历中的一部分,很享受每一个这样的过程。个人感觉,相比其他居住或旅行待过的城市比如纽约、旧金山、伦敦、阿姆斯特丹和墨尔本等而言,惠灵顿是最能呈现文化完美的城市,没有之一。在惠灵顿,移民语英语与土著毛利语以及文化展现出两者的平衡,又能夹杂着其他移民国家的语言与文化,诸如印度、马来西亚和中国等。以毛利人的独特欢迎仪式来开始,鼻子贴鼻子的传统毛利欢迎礼仪意味着他们愿意分享空气与呼吸,通过毛利语欢迎歌等,让自己体会着一个完全不同的世界。这样的当代文化习俗将永存我的记忆中,也教会自己开放、理解和拥抱这个世界。