The Swedish collector Inger Wästberg is a big advocate of Swedish contemporary jewelry and has helped to bring more attention to it. Starting in March, the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm will be featuring an exhibition of international jewelry called Open Space—Mind Maps. This is the first jewelry show to take place in the museum in 30 years. Inger had something to do with making that happen. She has also published a book called Contemporary Swedish Art Jewellery to promote the work she sees being produced there. How much influence can a collector have?

Susan Cummins: Inger, thanks for doing this interview. Can you give us a brief overview of your background in politics, social services, education, and so forth?

Inger Wästberg: I started early, 24 years old, as the political adviser to the Commissioner for Culture in Stockholm City. Later on I was a liberal member of the Stockholm City Council. I was also vice chair of the board of Stockholm University. I studied social science and was engaged with young people with disabilities. That led to international contacts, and to the position of Director of Planning at the Social Care Committee on the Stockholm County Council. After that I went on to become senior advisor to the Swedish Minister of Social Affairs and eventually I was appointed Director General of the Office of the Disability Ombudsman.

This 30-year-long career in politics and administration has been characterized by my work for change. I led the closure—and replacement by modern care—of the old institutions for people with disabilities. I was responsible for the new law-complex on individual care.

After this I chose to follow my husband to New York, when he was appointed Consul General of Sweden. I have always loved New York and have been there a lot professionally—so that was an easy decision.

In New York I made connections in arts and design and I was asked by the Bard Graduate Center to curate a small exhibition on contemporary Swedish silver.

Coming home from New York, after five years, I got a master’s degree in art history by writing a thesis about contemporary jewelry.

How did you first become interested in contemporary jewelry?

Inger Wästberg: I happened to see a necklace by Swedish artist Mona Wallström and bought it. It drew my attention to that kind of jewelry. A year later I looked her up and we met. She introduced me to other artists in Gothenburg.

When did you start collecting contemporary jewelry? I understand that you collect only Swedish jewelry. Is that true? Was that the case from the very beginning?

Inger Wästberg: I found that modern jewelry was a very good place to start a conversation and led to opportunities to talk about Swedish art and design. I therefore started to acquire jewelry to wear in New York—where we had very numerous social commitments.

Most of the pieces in my collection are Swedish, but I recently bought one by Carina Shoshtary and another by Kalliope Theodoropoulou.

Did particular artists or curators help you to decide which artists to collect in the beginning? If so, who were they?

Inger Wästberg: I learned through Mona Wallström. But I have not had any special advisors. I have followed my own flair, taste, and political interest.

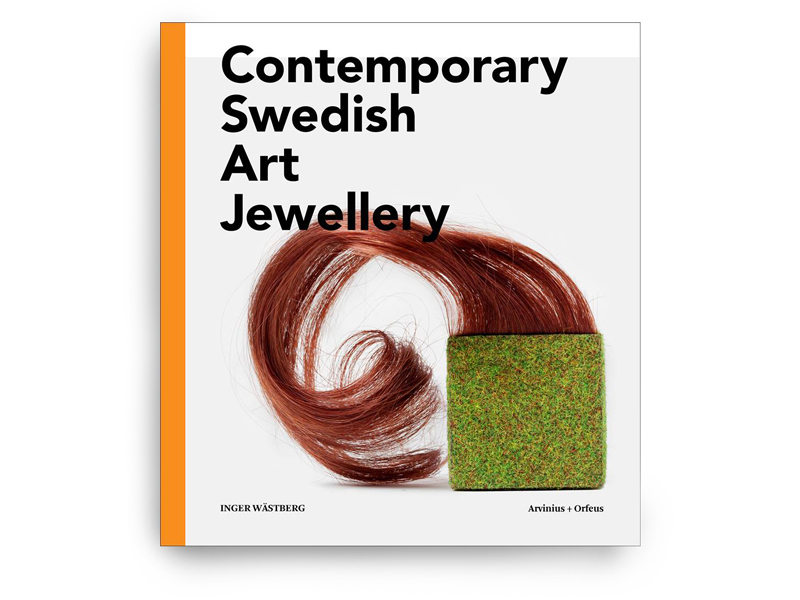

You have published a book called Contemporary Swedish Art Jewellery. How did it come about? Was it a project you conceived and funded yourself?

Inger Wästberg: The publisher had heard of my studies and asked me to write a book on another theme, but I suggested writing on contemporary art jewelry. I got some sponsorship for the book from foundations and the Liljevalchs Art Museum.

In your book you emphasize the feminist perspective of contemporary jewelry. Do you want to expand on your ideas generally and in Sweden in particular?

Inger Wästberg: Well, I have always been a feminist myself, and today feminism is very strong in Sweden. Many of the artists comment on gender equality and the traditional role of jewelry as a gift from men to women.

Do you think there are particularly Swedish characteristics in the jewelry made there?

Inger Wästberg: Not really. You will find a lot of references to nature—which we often think of as Swedish—as well as feministic comments. But this actually mirrors themes in international contemporary jewelry. Many people still associate “Swedishness” with modernism and silver. But that is not the case anymore.

You have obviously been a very proactive collector. What do you think should be the role of the collector in the jewelry field?

Inger Wästberg: I think that the foremost collectors should be the museums, and I have tried to promote that. For my own part I have of course mostly acquired jewelry in my taste, but also wanted to be in the forefront of the artistic development in the field.

This spring Berndt Arell from the Nationalmuseum has scheduled an exhibition called Open Space—Mind Maps: Positions in Contemporary Jewellery, curated by Ellen Maurer Zilioli and featuring 30 international artists. He notes in the brochure that this is a sequel of a show staged 30 years ago. Do you know the story behind how he became interested enough in contemporary jewelry to stage this sequel?

Inger Wästberg: I contacted Berndt Arell and suggested that the Nationalmuseum, which has a commitment to collecting jewelry, should—30 years after the groundbreaking exhibit Nya Smycken/New Jewellery (1985/1986)—make a new exhibition, stressing the art in contemporary jewelry. The background was that I had studied—and criticized—the acquisition policy at Nationalmuseum.

After that I brought Berndt Arell to Schmuck in Munich. At the AJF dinner he really comprehended the latitude of the contemporary jewelry scene.

I also suggested a few persons as curators, and he chose Ellen Maurer Zilioli.

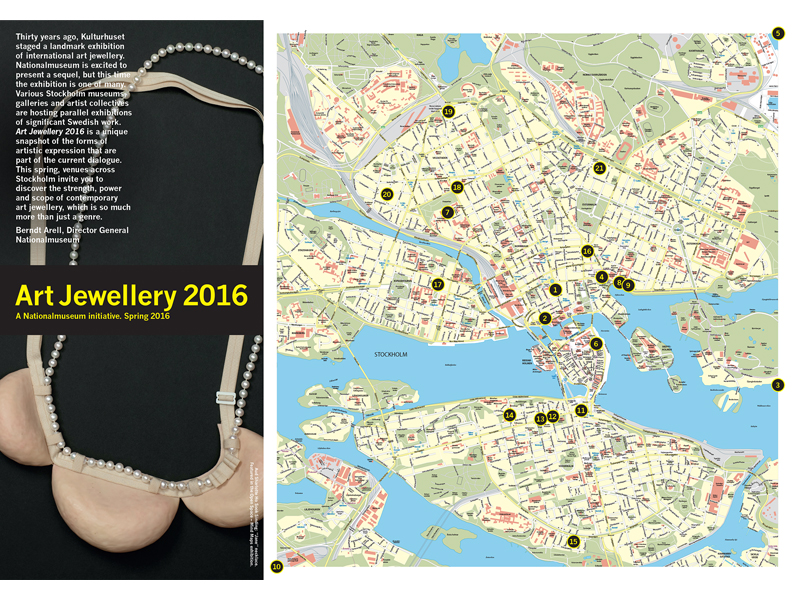

I understand this show is now surrounded by 20 other shows in Stockholm. These are taking place in galleries, studios, and shops, and are organized by various makers and curators. It is like a small Schmuck. Is that the intention?

Inger Wästberg: There will be 20 sideshows. The most interesting will be there and in five other museums and at Svenskt Tenn, the most classic Swedish design store. The exhibit at Nationalmuseum will be international, but the other shows will highlight different Swedish artists.

Are there plans for it to occur again next year?

Inger Wästberg: This is the first one in 30 years, I hope it will raise interest for contemporary art jewelry. Even if nothing more is planned I hope we will not have to wait for another 30 years.

Where can a guide to the shows be found? Is there a website?

Inger Wästberg: Here is one for the show at the museum. You can also get a special map of all the events and more information from Anna.jansson@nationalmuseum.se. And at Schmuck I will be handing out a map with all the venues in Stockholm.

What is most exciting to you about what is happening in Stockholm this year?

Inger Wästberg: It is that in such a short time we have achieved the ability to present a broad spectrum of contemporary jewelry. At the main exhibition—Open Space, Open Minds—you will find an international overview. And at the sideshows you will get to know most of today’s interesting Swedish jewelry artists. During this period of time we will certainly dominate the Stockholm art scene.

Thank you.

INDEX IMAGE: Inger Wästberg with a brooch by Hanna Hedman, photo: Catarina Lundgren Astrom