Also in this series:

- Indigenous &: Placing Practice While Being Displaced (with Teresa Faris)

- Indigenous &: Having Roots to Grow in New Directions (with Elias Not Afraid)

- Indigenous &: Tradition Meets Technology (with Pat Pruitt)

Happy Indigenous Peoples’ Day! This article launches a new interview series. It is called Indigenous &. A common thread will tie them together. All the interviewees identify as Indigenous. And they all live in North America right now. The ampersand in the title serves as an opening. It invites discussion of parts of life that intersect, interweave, and interact with Indigeneity. These are visible in the artist’s studio practice. They can also be seen in the work they produce. That “&” is also a way to enter specificity in nation, gender, sexuality, and other aspects of being human.

This series was inspired by talks I had with maker Tania Larsson. I previously interviewed her for Garland.[i] Hearing her express the diversity in technique, aesthetic, and material that is grouped under the term Indigenous was exciting. It also made me realize how much I still have to learn. I saw there are things I may never understand but still need to be conscious of and respect.

The title of this series comes from an interest in intersectionality. The term was coined by UCLA and Columbia law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. It has seen a revival in feminist scholarship. The term’s original intention referenced black women and the law in the United States. It has since taken on a more expansive meaning. It has evolved into a more broadly used term to unpack many concepts and happenings. It shows that overlapping factors and demographics intersect when looking at many different circumstances, primarily in social justice. It is impossible to separate them from each other.

These interviews will only touch on the broad diversity of work made by Indigenous jewelers. I hope they will offer starting points. I want others to look and explore more from a place of solidarity. Interviewees have provided recommended resources and other makers to look at. This makes the interviews an entry point. You can dive deeper and fall into rabbit holes.

You’ll notice some questions repeat between interviews. This is on purpose. It shows just some of the possible diverse answers. Other questions dive deeper in specificity to certain works and ideas of each maker.

This series acts as a tool for thinking when approaching Indigenous work. It is not an authority. Each interview will clarify and also complexify how, who, and what we think about when we see the terms Indigenous and jewel(er/y) together.

###

I met Brian Fleetwood at a round table discussion for Metalsmith magazine during a SNAG conference. We approached each other after the discussion. We realized we had similar interests in writing practices and equitable representation in the discourses of adornment and jewelry. In this interview, Fleetwood touches on accessibility, both in regard to providing information and skills to his students but also to wearers and viewers of work who may not have the money to purchase large works. He also opens a conversation on what it means to be a maker who is neurodivergent. I hope this discussion will continue regularly to further complexify and enrich how we see makers navigate their individual practices.

matt lambert: As this is a series with the intention of celebrating Indigenous artists, what part of your background would you like to share?

Brian Fleetwood: I’m a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma (Mvskoke, in our own language). I’ve got mixed European heritage as well, but I don’t really know where those ancestors came from.

Where does your interest in organic forms come from?

Brian Fleetwood: A lot of places, and I’m sure that my aesthetic is informed by things I’m not even consciously aware of. I think there are probably three main sources for this interest: a personal fascination with and background in biology and biological structures; Mvskoke teachings about the relationships between living things and art practices that abstract from biological forms (especially our floral beadwork); and a practice that involves processes I have little control over once they’ve been set in motion.

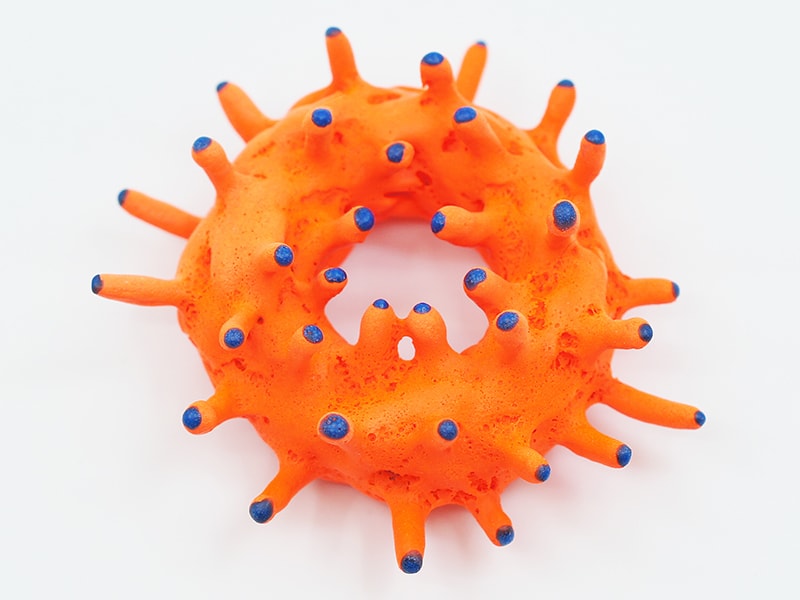

As an autistic person, one of my “special interests” as far back as I can remember has been biology/ecology/evolution, and the nuance and complexity of the relationships that all living things share. I’ve got a thing for dinosaurs. I love that organisms which seem so alien and inscrutable to people—fungi, plants, single-celled life, any number of invertebrate animals—are literally relatives to us. This runs parallel with traditional Mvskoke creation stories and cosmologies that emphasize the relationships between us and our nonhuman relatives. In this vein, a lot of the components of my work are informed in one way or another by Southeast abstract floral beadwork designs. Ultimately, I also want to make work that behaves, at least in part, in ways that are similar to living things, and work in a collaborative way with material and process wherein I set a process in motion and then give up control to allow that process to come to its own natural conclusion.

And this aesthetic is intended to serve a purpose. I want to make work that interacts with the human body to subtly urge people to reconsider their relationships with the world around them and to recognize that many of the hard lines that we draw between things, and especially between ourselves and the world around us, are cultural constructs rather than genuine distinctions that exist as a fundamental property of the universe.

Are there any specific processes or aesthetics that you use that are specific to your tribal affiliation?

Brian Fleetwood: I do make some work with processes and materials based in our historical cultural practice, like a bit of shellwork. I also do some work with culturally specific forms such as gorgets (a type of pectoral/neck ornament). However, I’m personally hesitant and cautious about making culturally specific work that exists outside of that cultural context, so these specific forms and processes only rarely show up in my public work. But, like I said before, much of the organic aesthetic I use is informed at least in part by Southeast floral beadwork.

Where/how did you learn these processes?

Brian Fleetwood: I’m lucky to have had some incredible mentors from my people who have had the patience and kindness to share their knowledge with me, in particular Sandy Wilson and Kenneth Johnson. There are also resources made available through the Muscogee Nation government to support the continuation and revitalization of culturally based making practices, and I’m currently using some of these resources to expand my knowledge and skills with materials and forms that I don’t have much experience with.

Other mentors who influenced the way I engage with materials and processes are Mark Herndon, Chris Ramsay, and Susie Ganch.

I also love working collaboratively and I teach. Learning how to relate to work and process in new ways is almost inevitable when engaging in those kinds of things.

You now teach as an assistant professor in studio art at the Institute of American Indian Arts. What makes your classroom at IAIA unique compared to institutions that do not focus on Indigenous people?

Brian Fleetwood: IAIA is unique as an institution on the whole. All of our students are required to take Indigenous Studies classes as a part of coursework, and even our math, science, and other gen-ed coursework centers on Indigenous perspectives and authors. But I think first and foremost the biggest difference is our students. This is of course wild speculation, but I don’t know if there’s an art school on the planet that has the diversity of our student body. In any given semester our students hail from dozens of Native communities, and currently I have students from Indigenous nations that span from above the Arctic Circle to the Andes in Peru. Each of our students brings their own specific cultural knowledge and experience to the classroom, and this incredibly dynamic and diverse community continues to challenge and change my perspectives on jewelry, art, and making.

I try to cover most of the skills and processes in metals that people expect to find in a contemporary jewelry class, with an emphasis on those common to Indigenous metalsmithing practices. But I also work hard to emphasize that while metalsmithing and metal fabrication are important—even essential—to many jewelry traditions, there are just as many that include few to none of the materials and techniques that much of the West synonymizes with jewelry. I encourage my students to center their own personal and cultural perspectives on making and on artworks seated on the body in the work they make, as well as in the discourse they bring to the classroom.

I also try, given jewelry’s relationship to the body, to include Indigenous perspectives on the body as a part of our theoretical discourse—including the idea that individual bodies belong to the land they inhabit, and seeing the land itself as a body with agency and rights. (I think there’s a really fascinating relationship between jewelry and work that fills or intervenes in physical spaces, such as installation or land art.)

Is there anything you’d like to see change in the jewelry and metalsmithing discourse?

Brian Fleetwood: Oh, yeah. I’d like to see a decentering of European metalsmithing practices in discussion and criticism in the field. I’d also like to see discourse that critically examines the taxonomy of art, making, and jewelry to challenge Western and English-speaking hegemony over interpretation and categorization of material culture in general.

When making work, do you have a specific audience or venue in mind?

Brian Fleetwood: Audience is kind of tricky when it comes to jewelry, because I want as wide and diverse an audience as possible, but jewelry is so tied up with class and access issues that most people don’t think of it as anything but a luxury good or prestige object, at least in the West. Signaling status and wealth are common purposes of jewelry but only as a function of jewelry serving as a tool for performing identity in general. As far as I’m concerned, artwork that is seated on the body is the most fundamentally human format for artwork, and I don’t think people’s access to art and material culture should hinge on their income or class.

In the end, I make work that covers a wide range of price points. I do make work that sells at a cost that many if not most of the people I interact with would consider an extravagance, and I quite like this work and enjoy the ability it gives me to experiment with aesthetic, process, and material, but the main function of this work is to inform and fund the work that is, frankly, most important to me.

I have a few bodies of work that are designed to encourage people to engage more deeply with my work and jewelry in general, and to create as much access as possible to the work. This work is pretty diverse and ranges from a project where I interview people and make work for them as a gift based on the interview we hold, to installation work that includes takeaway jewelry components that I usually refer to as “spores,” to a project where I make simple open-ended jewelry kits that are distributed cheaply or free to as many folks as possible.

We’ve talked previously about the accessibility and the selling of your work. Who do you want to access your work, or how?

Brian Fleetwood: Anyone, and in any way they can! I have work in galleries and shops. Form & Concept, in Santa Fe, NM, is my main venue. They do great work, and the diversity of work and artists they exhibit is phenomenal. If someone wants some of my work, especially if they don’t want to have to wait for it, this is probably the easiest way. But I also make an effort to work with public schools, museums, community centers, and other groups to arrange workshops and distributions of some of this work as widely as possible. I also sometimes just leave work around so that people can find it. But anyone who reaches out and wants something is likely to be able to get something. I can’t always do the free work quickly, but it’s important to me and, even if there’s a wait, anyone can get something.

Ideally, I’d like whoever acquires my jewelry to wear it, even though some of my bigger and weirder work can be a challenge for some folks. This wearing/performing of the work makes the wearer complicit and allows the work to move through the world in a way that is unique to jewelry and potentially increases my audience manyfold. This is the most exciting thing about jewelry for me, the way it combines some of the elements of installation and performance, the way it rides a body in order to drift through the world.

What are some thoughts for the future? Is there a place you’d like to show or a project you’d like to make happen?

Brian Fleetwood: Absolutely. I’m always in the process of spreading myself too thinly. I’m in the beginning stages of a project called Jewelry Dispenser. I’m restoring some old gumball/toy vending machines to leave in temporary, constantly changing locations, where folks will be able to get a small random-ish jewelry object for 50 cents, or perhaps in exchange for something less tangible.

I’m also expanding a line of free jewelry kits I’ve been producing. The next kits are going to be screen-printed single sheet kits and/or zines with folded paper jewelry patterns, and they should be out relatively soon.

I’m also in the planning and design stages of creating a number of new public jewelry projects or jewelry interventions, including some that use technology to create work responsive to bodies or environments.

I’m doing research to inform some collaborative community exhibitions that experiment with venue/format. I want to really challenge people’s perceptions about how art can live in the world outside of formal gallery and exhibition spaces.

I’ve got a curatorial project in the works for the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. The exhibition is scheduled to open in Spring 2022 and will explore the history of contemporary Indigenous jewelry as it relates to the Institute of American Indian Arts. There are a number of research, writing, and exhibition projects I’m in the very early stages of, that are intended to create more visibility for Indigenous jewelry practices.

The last new thing I’m working on, and it’s probably a long way off, are some explorations of the relationship between jewelry and physical spaces outside of the body. I’ve got some ideas I’m pretty excited about that hopefully end with work that blurs or breaks down some of the distinctions between jewelry and land art, installation, or other kinds of work that exist between bodies and space.

Where can readers see more of your work or follow what you’re doing?

Form & Concept, MoCNA, Center for Craft, and random locations around Santa Fe and in towns I visit. I’ve done some work with a local alternative art venue, Axle Contemporary, a mobile gallery made from a refitted food truck. I’m very bad at self-promotion and social media, and many of those parasocial things that people expect of folks working the arts, but I try to be responsive if people reach out. I can’t always respond quickly, but I do my best.

Do you have any recommended artist or other resources to look at?

Brian Fleetwood: Yes!

Any list of artists I give is going to inevitably leave out some essential and important folks. That said, I’d recommend people check out the following Indigenous folks working with jewelry and adornment: Kenneth Johnson, Keri Ataumbi, Wanesia Misquidace (who combines traditional birch bark work with contemporary silver work), Tania Larsson, Anangookwe Wolf, Carly Fedderson, Kevin Pourier, JQ Nightshade, Nicholas Begay, Hotvlkuce Harjo, Hollis Chitto, Ken Williams, Jr., Jamie Okuma, and Denise Wallace. I might argue the patron saint of Indigenous jewelry would be the late Charles Loloma, a mid-20th-century Hopi jeweler and the first jewelry faculty at IAIA. If you’re involved with jewelry at all and aren’t familiar with Loloma, please do yourself a favor and check out his impeccable work.

Some museums where folks can see Indigenous jewelry work: MIAC, the Wheelwright, the Heard, and the Eiteljorg. The National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum often has great examples of Indigenous adornment and metalwork—Indigenous cowboy culture is definitely a thing. There are some beautiful examples of historical and pre-contact Indigenous adornment at the MET, but it’s also a monument to plunder, so … I don’t know, keep that in mind if you visit that collection, I guess.

If anyone lives near any Native American or First Nations communities, you might look into whether they have a cultural center or museum. If so, they likely have information on material culture that probably includes adornment.

Every August in Santa Fe is Indian Market, the biggest Native art event in America. In addition to Market, there are a number of concurrent events and exhibitions. If someone wants to get an overload of Indigenous jewelry, and art across pretty much any media, Market would be the place.

Thank you, Brian!

TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THIS ARTIST AND SEE MORE OF HIS WORK, WATCH OUR RECORDING OF AJF LIVE WITH BRIAN FLEETWOOD.

[i] https://garlandmag.com/article/tania-larsson/