When the AJF tour group visited Italian goldsmith Stefano Marchetti (along with Annamaria Zanella) in September of 2016, it came to our attention that an interview with this skilled artist, who has such a strong voice, was woefully missing from our archive. Katja Toporski asks him about his training, material choices, and future plans.

Katja Toporski: You trained as a goldsmith in the famous tradition of the Padua School in Northern Italy. Can you describe your educational experience there?

Stefano Marchetti: I trained at the Istituto d’Arte Pietro Selvatico in Padua, which recently changed its name and plan of studies and is now called the Liceo Artistico Pietro Selvatico. It’s a high school. At that age I wanted to become a painter, but my father, who recently passed away, suggested that I should have a look at that school. I was totally fascinated and so I decided to study jewelry instead of painting. Thanks, Dad!

I started my training when I was 14 and graduated at the age of 18. In my opinion, it’s important to start training when you’re that young. Can you imagine someone who wants to become a piano player and touches the piano for the first time at the age of 20? Nowadays, considering that in contemporary jewelry real technical skill isn’t required, we can easily understand why the training often starts as late as that.

For me, the most important thing has been finding the right teacher. I was lucky that Francesco Pavan was teaching there. That made the difference.

You followed your initial training with four years of studies in sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice. Is this a typical path for an art jeweler in Italy to take, or did you personally feel the need to deepen your studies of form with different materials and scale?

Stefano Marchetti: Well, when you’re only 18 years old, you often still need to learn. At that time there were no academic studies dedicated to jewelry in Italy. I wanted to learn more, so my choice was the “nearest” discipline—sculpture.

I went to Venice mainly to understand what an artist is supposed to do today, by finding the reasons that brought our society to our contemporary aesthetic.

You’re known for making jewelry where strong geometric forms feature complex gold and silver inlay surfaces reminiscent of mosaics. The metal appears to be worked to its breaking point, and overall the pieces gives the impression of a fragment of a precious ancient artifact. Where does your original inspiration come from, and how do your pieces relate to mosaics specifically?

Stefano Marchetti: Since I was a kid I’ve been in love with metal, fire, chemistry, computers, etc. My mosaics are just the merging of all these ingredients.

Of course, Venice was the perfect place for developing this kind of aesthetic. There I realized that it was possible to “import” the glass technique called murrina veneziana into jewelry. The poetics of fragments also comes from the decay of that town. But, mainly, the aesthetic of my earlier works has to do with a kind of resistance, a will of opposing some of the contemporary models in jewelry.

You work mainly in precious metals—have you considered other metals or alternative materials as having a role to play in your jewelry?

Stefano Marchetti: I do use many materials, and if it were possible I would love to try all of the ones that exist. Concerning precious metals, a kind of ideological “war” against gold and technical skill started in contemporary jewelry a few decades before my training as a goldsmith. The result is now evident: It’s statistically rare nowadays to see gold in this discipline. I use gold because I like it, I think there’s still a lot to do and a lot to invent with it, and, in any case, I love swimming against the flow.

I must be clear: I do not at all think that gold and technical skill are necessary to yield good works. Actually, I think that, more often than not, they produce boring results. On the other hand, I think that the absence of technique and the use of nonprecious materials do not guarantee interesting objects.

It’s not the material that creates the result, but our ability to “fertilize” it with ideas.

You have created a group of works titled Plastic Gold featuring rough surfaces of a nondescript material. What is that material, and does the title refer to the material itself or its plasticity?

Stefano Marchetti: When I made those works, I was in a time of crisis. After the mosaics I was feeling empty, I wanted to act in resonance with the contemporary debate. I wanted to prove myself to be able to understand a different side of the contemporary jewelry scenario–plastic. (Actually, plastics are not really that contemporary, the oldest kind was invented 150 years ago.) I wanted to use something more contemporary, so I prepared a material that was neither gold nor plastic, but simply something else. In the last pieces I used nanomolecular metals mixed with synthetic resins.

In a way those are the most “superficial” pieces I’ve made. I didn’t think much, I just made.

In your time-lapse video, titled Ricerca Periodica, you investigate the relationship of time to artistic endeavor. You perform this research only once every 10 years, resulting in a single brooch on each occasion. Could you explain this project and also talk about how it informs your overall work?

Stefano Marchetti: Ricerca Periodica/A Study in Recurrence was made by Francesca Ferrario. She works in the stop-motion industry. Stop motion and time lapse were the perfect techniques for talking about time.

Here’s the explanation. Back in 1996 I asked myself, what kind of relationship exists between time and artistic endeavor? When can a project be considered finished?

Well, I found an answer, a few years later … namely: Once I choose a theme for this study, I can only create one piece of jewelry every 10 years, over the course of my life. This way, if I’m very lucky, I may be able to make another four or five pieces.

The theme of this study has always been, from the outset, about currents: in bodies of water, or blood vessels, or electromagnetic resonances. The first piece, made in 1996, was a map of Venice and the land surrounding the lagoon. In 2005, I made the second piece: a part of a human torso portraying the shoulder and upper arm within which one can imagine the flow of blood. In 2016, the third piece: I wanted to represent planet Earth, intersected by divergent trajectories; or clusters of data transmission; or possibly even airplane tracks. The resulting brooch represents an homage to these trajectories. Now I can start thinking about the next piece, which I will make in 2026.

Does your knowledge of the history of jewelry play a role in your work, and do you consider it important to research techniques, materials, and ideas of jewelry in different eras from the past?

Stefano Marchetti: Well, of course yes. How can we make something new today without knowing what was made in the past? The risk is that of reinventing the wheel. Everything is somewhat reinterpretable, but I think it isn’t a good idea to do it without even knowing whether it was already made. That approach would offer hilarious results in any other discipline. Can you imagine a scientist trying to patent Edison’s bulb today? Well, in contemporary jewelry this kind of event does take place, usually without any notable reaction. It’s something to reflect upon.

Your piece titled Homage to the Low Energy Nuclear Reactions: LENR II won you last year’s Herbert Hofmann prize at Munich Jewelry Week. Please explain the idea behind the piece and what led you to abandon precious metals in favor of wood for this brooch.

Stefano Marchetti: In fact, that piece is made of many materials, e.g., platinum and a considerable amount of gold, too. Each material is used for its chemical and physical properties. A nonconductive material was required as well, and I decided to use wood.

A more detailed answer concerning the brooch Homage to the Low Energy Nuclear Reactions: LENR II may be found on the web in an abstract where I clearly explained what I wanted to do. It’s the most complicated piece I’ve ever made. Here’s a quick summary:

Today, it seems possible to control the transmutation of metals. The philosopher’s stone does, in fact, exist. The so-called low energy nuclear reactions (LENR) would allow for the recombination of different elements’ nuclei into metallic transmutations.

Well, as soon as I heard that the philosopher’s stone existed, I knew exactly what to do with it: make a piece of jewelry!

The brooch represents a study on the electrochemical compression of hydrogen based on experiments conceived by the pioneer of nuclear fusion, Yoshiaki Arata. The cathode is a needle made of constantan—CuNi44—and is the very one I used during the reaction.

Of course, inside my brooch there has been no fusion of atomic nuclei. Nevertheless, the structure of the hollow CuNi44 electrode really did absorb a small amount of atomic hydrogen through a reaction that, not so many years ago, was considered by many to be pure folly. What an easy and fascinating transformation. First, via electrolysis I split the water into diatomic molecules of hydrogen. Then I split those molecules into atoms. Finally, from those atoms I obtained subatomic particles. A flux of protons was moving freely inside the metal. Then it turned back into molecules—a real alchemical dance.

Which direction do you see your work taking in the future? Is there anything specific you have in mind?

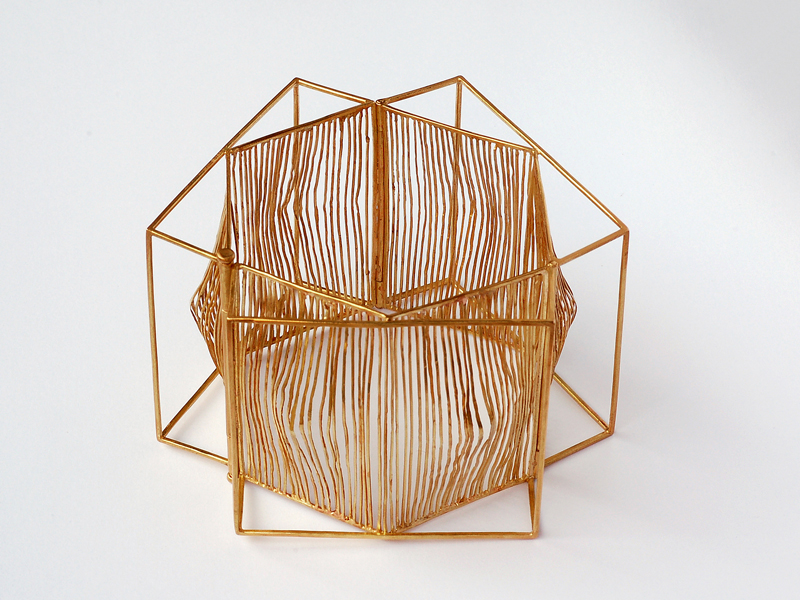

Stefano Marchetti: Yes! Right now I want to create sketches in metals with the same kind of look and resolution as you would obtain by using a pencil. I recently succeeded and I will soon show the first results at Schmuck, during Munich Jewelry Week.

Concerning the future, well, as soon as I find something capable of tickling my brain, I’ll work on it.

Last fall a group of AJF supporters visited you in Padua as part of their tour of art jewelry in Italy. Please talk about your impressions of their studio visit.

Stefano Marchetti: It was really nice; I always like to talk about myself and about my work, I’m so egocentric! The group was composed of many interesting people. I hope I didn’t annoy them too much with my maniacal explanations. Susan Cummins and Marie-José van den Hout organized everything perfectly. My friend, Annamaria Carrain, generously offered her home for a lecture.

Yes, I have a very good memory of the whole experience.

What book have you read recently that impressed you?

Stefano Marchetti: I have minor problems with my eyesight, so I read mainly what I can find on audiobook. I love to listen to books while I work, and sometimes the radio chooses instead of me.

One of my favorite books is Le Città Invisibili, by Italo Calvino, but I read it many years ago. Recently I started reading, once again, Isaac Asimov’s Foundation. Concerning the field, I was impressed by the ruthless lucidity in L’Hiver de la Culture, by Jean Clair.

Does anything outside of jewelry influence your work?

Stefano Marchetti: … The world.