The past decade has given most independent art practitioners occasional cause for dismay, as culture budgets get slashed and jewelry departments fight for their economic survival. In this climate, I find it particularly important to celebrate the resilience of jewelry dealers around the world: They have “made history” in all senses of the words, in the face of changing economic and political environments. Three dealers—in Holland, the United States, and Canada—are celebrating major milestones in their galleries’ long histories this year. I reached out to Paul Derrez, Mike Holmes, and Noel Guyomarc’h a few weeks before Gallery Ra’s 40th birthday, and they agreed to speak to their joys and tribulations in an unusual triangular conversation.

Dear Paul, Mike, and Noel,

I little while ago, I watched a documentary film called It Might Get Loud, about three fearsome guitar players: Jimmy Page (of Led Zeppelin), The Edge (U2), and Jack White (White Stripes). The documentary was unremarkable but for the amazing bits of guitar playing, and the devotion that those variously innovative players have for music history. The youngest, Jack White, presumably had Page, the eldest, as a model. But he mostly listens to music older than Page: rare country blues recording of old guys singing older music. White’s tenderness for old blues (and his raw reinterpretation of it) echoes a line from Paul, in which he describes three of Ra’s exhibitions from the 90s as “reviving the jewellery-world by relating to history and heritage, not as comment or irony. They connected to old values, without copying them, and with great sensibility.”[1]

Paul, that respect for history comes as a surprise: I assumed that your gallery made history precisely because it wanted to break away with tradition, that you became a dealer to promote something that was not easily accessible in Holland at the time.

In fact, what these anniversaries bring into focus is your roles as people who bet against conventions. So a first question to all three of you: How conscious were you of your role as missionary and history-maker when you respectively started in Amsterdam (in 1976), San Francisco (1991), and Montreal (1996)?

Paul Derrez: When I became part of the Dutch jewelry scene, in about 1975, there was a feeling of starting a new era for jewelry. We thought a total break with history and conventions was necessary. To gain new possibilities, we needed to experiment in many directions: in concepts, in designs, in materials, in relation to the body, in genders. We called the results experimental jewelry.

Some pioneers, such as Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum, had prepared this movement, but we wanted it broader, less formal, and less individualistic.

There was no audience or market for this kind of jewelry, so we chose the strategy of confronting, informing, educating, surprising, convincing… The gallery structure became the vehicle for this. We even thought we would replace the old jewelry world with our new ideas and attitude. Which of course was rather naive. Luckily that’s what you are as a youngster…

But we wrote history in a more modest way: A fresh new branch has grown on the big jewelry tree. It was a hard and complex job, but in the long term it worked!

But revolutions run the risk of developing new conventions and restrictions. To avoid this trap, new orientation and research in many directions was necessary. Connecting (again) to heritage, to historical and ethnic jewelry, offered new inspirations and possibilities. I don’t use the word “experiment” anymore as it points too much to “finding” something new. I now prefer the word “research” for developing new ideas. The internationalization in the last three decades has also enriched the jewelry field enormously.

Mike Holmes: Velvet da Vinci began as a lark. Like many jewelry galleries, Velvet da Vinci was founded by makers. My cousin, jeweler Kara Varian Baker (yes, her!), and I had both attended California College of Arts and Crafts and were searching with our pals for a venue to showcase our work. The big Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989 had damaged a freeway that ran through the center of San Francisco and it was in the process of being torn down, allowing an otherwise neglected neighborhood to be rejuvenated. In 1991, Hayes Valley was mostly empty storefronts, and we took the smallest, cheapest one ($400/month!) on the sunny side of the street. Velvet da Vinci was born.

Elaine Potter Gallery had been the topnotch craft gallery in the city but had recently closed due to Elaine’s tragic early death, and we felt there was an opportunity for us. Susan Cummins Gallery in nearby Mill Valley was the preeminent jewelry gallery in the US at the time, but we were interested in presenting craft in a different way. In the beginning, we exhibited jewelry as well as studio furniture, ceramics, and contemporary tapestry-making, but soon realized that jewelry was what we knew best. Since then the gallery has mostly focused on jewelry and metalworking.

Within a few years, the gallery had outgrown our local roots. We started showing work by artists across the country and by 1996 had organized Britain Now!, the first survey of the great new work coming out of the UK. This began a series of exhibitions highlighting jewelry from around the world, and Velvet da Vinci built a reputation based on these and other thematic shows. We have come a long way from the days when exhibitions were organized by 35-mm slides and letters though the post office.

Noel Guyomarc’h: Initially, the gallery’s concept originated from the desire to promote and stand for a few local artists whose work I liked. I opened, full of beliefs and enthusiasm, in a downtown building dedicated to culture and surrounded by many visual arts galleries. I didn’t have examples around me of galleries dedicated to contemporary jewelry. In Montreal, Galerie Jocelyne Gobeil had built an international reputation over a few short years, but had closed in 1994. The place where I had been introduced to contemporary jewelry practices, Bijoux Suk Kwan, closed a year later. I knew from personal research about places with global reputations, like Galerie Ra or Helen Drutt Gallery, but these seemed remote from me, and my ambition was not to lead a renowned gallery. I just wanted, as I do now, to defend a discipline.

It has often been a chaotic and difficult route: My first gallery was located on the third floor, in an arts community reluctant to craft and fragilized by an uncertain economy. In 1999, I closed it … but reopened a few months later on the street level. Determination paid off: Several exhibitions I curated at the beginning offered innovative thoughts about jewelry, about what that object could represent. Almost as soon as I opened, in 1996, proposals from international artists started coming in, and some Quebec museums got interested in the collections I was representing.

This work makes daily demands on you, and I didn’t let myself think about what I was building. But over the past 10 years, numerous new international proposals and prospects are helping me realize, in retrospect, how much ground I have covered. I still seek to defend and promote a discipline by selecting the work of artists that I consider a contribution to the field.

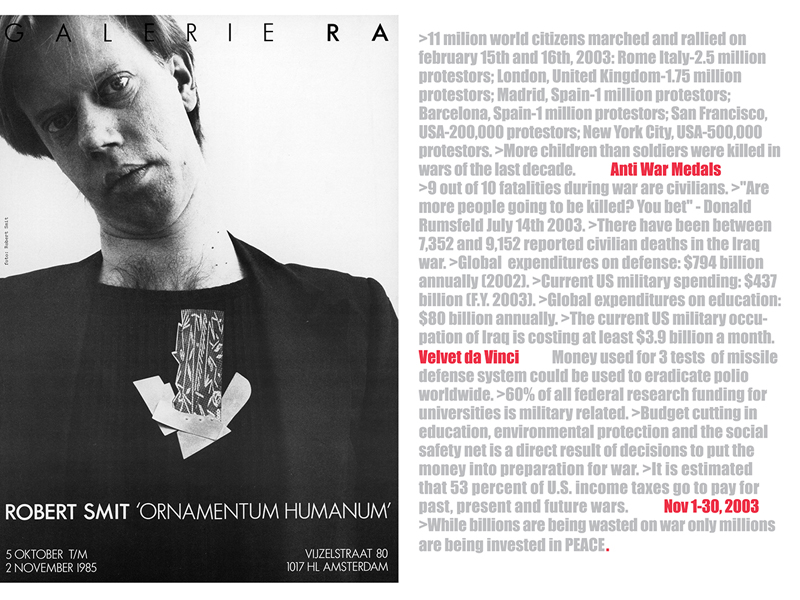

In preparing for this interview, I asked the three of you which exhibition in the history of the gallery defined you as a dealer—and in all three cases, your answer very much has to do with taking a position: Paul mentions the 1985 Robert Smit exhibition Ornamentum Humanum which made history by the fierce debate it generated between Smit (who had “returned to gold”) and Gijs Bakker, who furiously criticized the move as a treason to the ideals of new jewelry.[2] Paul describes how clearly marked his position was regarding the issue: “my disgust for prestige was so deeply felt, that I could not muster any affinity for Italian and German gold jewellery. I had explicit ideas about what the maker’s position should be and detested putting the artist on a pedestal as a bohemian genius. Ra Gallery typically regarded makers and their work as producers and products, as craftsmen who were socially engaged, without pretence.”[3]

Meanwhile, Mike chose as defining projects his Anti-War Medals (2003–2005), which he describes as a “very political exhibition in a field where Politics are normally carefully avoided,” closely followed by La Frontera (2013), which looked at the US/Mexico border. There are two issues here that interest me: How does the field of jewelry lend itself to creating “engaged art,” and how can selling art jewelry have anything to do with taking a stand?

Noel Guyomarc’h: Among the exhibitions I’ve shown, the most controversial and debated one was Impaired Visions, by Barbara Stutman in 1997. Stutman permits herself, through jewelry—objects that communicate—to criticize certain points of view. Using brooches, rings, and necklaces, she expresses, satirically, the perverse effects of images in the media, which she perceives to be an obstacle to the emancipation of women. Her use of textile techniques, something we associate with traditionally female crafts or pastimes, reinforces this stance. To acquire and wear one of her works requires courage and commitment; the wearer becomes a standard-bearer of certain taboo subjects, many of which are still very much in the news.

Other artists have similarly used jewelry for militant purposes. No longer active today, Christian Chauveau denounced the political and economic justifications of the global arms race and conflicts in works made in 1999. In another vein, Anne Fauteux’s Bijoux-Outils series (1996–2002), kind of contemporary artifacts, examined the popular beliefs in the object’s power. To pretend-resolve the ills of our society, she offered solutions in creating fanciful and spiritual jewelry: Anti-Bitterness jewelry, Keys of Hope, Embarrassment Container…

Environmental issues have more recently become a common topic for jewelers, who have been tackling the subject in a great variety of ways. Natural/Artificial, an international exhibition curated by Luzia Vogt in 2012, took hold of the subject by questioning notions of natural versus artificial, and looking at the range of human intervention on the environment. Luzia is a good example of an artist/curator challenging the status quo.

I would not say, however, that she is a lone case: Jewelry is an object of communication, of belonging, of identification. In contemporary practice, it is the outcome of a vision and reflection of the artist about the world, her environment, her art. The use of jewelry as means of denunciation or rallying call is in my view a truism. Most of contemporary jewelry is taking a stand.

Mike Holmes: Just running a gallery selling the kind of jewelry that our galleries do is taking a stand. Even after all these years, most people are still unfamiliar with the notion that jewelry can be anything other than personal adornment made of precious materials. That adornment can be made from less intrinsically precious materials and have become precious because of the concepts contained in the piece and/or the care of workmanship of that piece provides an intellectual engagement that my audience appreciates. I try to be careful about the political exhibitions that I have organized. I am not always looking for a new political “hook” that might trivialize a particular important issue. I don’t want to become an “issue-of-the-month-club.”

Providing a venue that supports and encourages the creation of accomplished new work seems to be my role at the gallery. A good example of this was Under That Cloud, in 2011, curated by Jo Bloxham at Velvet da Vinci. Contemporary jewelers from around the world had convened in Mexico City for the Grey Area Symposium when the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland erupted, grounding air travel and affecting millions of people around the world. The experience of these many artists being stranded in Mexico created some excellent work. Nanna Melland’s Swarm installation of hundreds of aluminum airplanes was born of this project and has grown and gone on to great acclaim at subsequent venues, including the Schmuck exhibition in Munich. Another less known but also wonderful piece born out of Bloxham’s exhibition was Caroline Broadhead’s Caroline portrait pair of beaded bracelets.

Paul Derrez: Most contemporary jewelry is “decorative arts”: beautiful objects with seductive shapes, structures, and colors, which contribute to making one’s outfit and personality more interesting.

Themes directly inspired by life and nature—like flowers or leaves—never do any harm, nor do abstract “plays” with lines and planes, both of which are OK. It’s about aesthetics, and some makers do this with fantastical results and a lot do them in a banal way. The fantastic ones, like Julie Blyfield and Sam-Tho Duong, I show at Ra with pride.

Some jewelry is questioning and intriguing, and uses unexpected themes, forms, materials, techniques, or combinations of these. Offering a more intellectual play, for people with confidence and attitude, that often acts as a conversation starter. And you need an answer when people ask you: What is it? (I sometimes answer: What do you think it is?)

And then there is jewelry which confronts. Which deals with personal, social, or political taboos. Which operates as a comment, a critique, or even an aberration. The most confronting kind of jewelry are badges. They were popular in the 70s and 80s, to show a—often explicit—point of view. At that time, a handful of Dutch contemporary jewelry designers played with that format: Marion Herbst ridiculed military decorations and Gijs Bakker did the same with royal jewelry. In the 90s, Gijs Bakker (again!) mixed religion with sport and addressed sexuality in his pieces. Around the same time, I made a series of phallic pendants—Face, Dick and Cross—to confuse gender stereotypes, and Pill-roulette-brooches to question the healing and stimulating role of pills.

These pieces are truly conversation pieces, but only for the courageous!

Nowadays we see “soft,” general statements, for example about nature or the environment, but no sharp and explicit ones. The growing demand for, and awareness of, political correctness has led to self-censorship. And neither artists nor their dealers want to be stabbed because of a message on a brooch…

So we enjoy the decorative arts, and there is nothing wrong with that!

Noel Guyomarc’h: Paul, what were the reactions of your clients regarding the third kind of engaged work (Bakker’s or Herbst’s), or the heated debates that surrounded the Robert Smit exhibition? Was your clientele buying and wearing these works? Were they also interested in the debates that took place within the community, and mostly concerning the community?

Paul Derrez: Yes, the clients were also involved in the polemics, and bought and wore these pieces as statements.

Benjamin Lignel: Paul, do you find that some works that may not be very political become so when worn by certain people—i.e., is there such a thing as “political wearing,” and does contemporary jewelry lend itself to that, as well as badges?

Paul Derrez: Badges/buttons can make a clear (political) statement. A badge expresses with text or image a sympathy, a piece of advice, a comment, or a wish: Vote Trump!, No nukes! Free abortion now! Jewelry can play such a role as a visual message too, as mentioned in the examples above. The message can also been created by the wearer, the situation, and the moment.

Madeleine Albright played this game on a high level with mostly uninteresting costume jewelry. A good example of “political wearing.” In wearing contemporary artist jewelry, there is in general no political message. The only message is: Look at this special piece. It makes me special, too! I personally like to wear pieces which are a bit subversive, which deregulate stereotypes or good taste, but I would not call that political.

Benjamin Lignel: Part of your galleries’ mission is to evolve with the times—and adjust to or surf on social changes: Paul mentions the emancipation of women in his 40-year anniversary publication. (“Luckily the emancipation of jewellery and women seemed to go hand in hand. The cultural and financial independence of women opened.”[4]) What have been the biggest social changes, in the last 10 years, that have reshaped your mission? How have you addressed them?

Mike Holmes: The impact of the Internet has been profound. It is the most efficient way to reach my customers, but also by far the way that most contemporary jewelry is consumed. Facebook, Klimt02, and Art Jewelry Forum, and countless other websites and blogs, provide easy access to new developments in the field. And Instagram has almost overnight become the primary way our audience sees new jewelry. In just over a year, Velvet da Vinci gallery’s Instagram feed has gone from 0 to nearly 10,000 (thanks, Amy Tavern!). These clicks do not usually turn into sales, but happily sometimes they do…

Noel Guyomarc’h: The most transformative changes have been the eruption of online communication and of social media into the field. We have had to learn to manage and to feed all these different platforms, which in turn offer a boosted visibility to both galleries and creators. Sometimes online traffic makes us forget the role of galleries, which function as “gatekeepers” in their choices and selections of works, and wage a permanent campaign of education and awareness. It is thanks to the directors of all the seminal galleries dedicated to jewelry—like Paul, Helen Drutt, Barbara Cartlidge, or Marianne Schliwinski, to name a few—that there are now important collectors of contemporary jewelry, and that museums are building contemporary jewelry collections. The galleries offer a physical visibility to the artist’s work, which not the case with the ’net.

Still, sites like Art Jewelry Forum or Klimt02 are doing an incredible job on several levels, educating, promoting, discussing, and introducing contemporary jewelry to new audiences. The pertinence of their articles and publications gives credibility to this effervescent environment.

And today, whether we want it or not, every dealer (and artist) is obliged to feed their social media platforms, update their website … and do this extra work that is expected of them!

Paul Derrez: From the start of Ra Gallery in 1976 to now, there have been immense technological improvements: the fax, the copier, the computer, the mobile phone, the Internet… Traveling also became much easier and cheaper. Possibilities grew and improved enormously: You just deal with it.

But in managing a gallery, a lot has stayed the same: To keep strict opening hours, to have interesting stuff, to have an adequate display, to be nice to visitors, to provide information, to offer service. The ingredients for success are basically similar to that of a butcher shop. Being raised in a jewelry-store family, I got this base in my genes. I believe in the power of consistency and continuity. (While teaching Professional Practice at Rietveld Academy some years ago, the students’ enthusiasm for the pop-up store model drove me crazy!)

Writing the Gallery Ra story for the new book Ra Gallery 40 Years Cherished, I was amazed to realize how consistent Ra has been over all those years.

And how consistent the audience is: a relatively small number of people, looking for works which appeal and convince, because of their smartness, beauty, or craftsmanship. My role as a gallery owner is—just—to be a good intermediary…

Benjamin Lignel: We often forget that dealers, like artists, must fight for the survival of their gallery, and often can’t do it without a large support system that takes many different forms: grants and specific financial arrangements from the state (Paul, for example, recalls a 15% discount granted to collectors for buying from Dutch artists, later replaced by interest-free installments not limited to Dutch makers[5]), the support of clients and commentators turned supporters … and the invisible, but crucial, help of partners. (Paul, again, speaking about the year following his move to Vijzelstraat: “Thanks to a husband with a steady job I survived these hard times.”[6]) Can you speak about the precariousness of the gallery business, and how you all managed to last for so long? Can you speak about the opportunities that this job represents? If you had to write a letter of advice to your younger self, what would your recommendations be?

Noel Guyomarc’h: To maintain the gallery during the first years, I kept a second job. It was exhausting, but I was passionate and persistent. In 2001, I was able to produce an income, and started receiving local support: Some exhibition projects have received financial support from cultural organizations, mainly for the promotion of Quebec artists.

There were still some difficult years. Like Paul, since the beginning of my gallery project, encouragement and my partner’s support have been and still are essential. (Since 2012, when he started working as the director of the Montreal Jewellery School, he has become much more aware of the importance of dealers.)

I have also tried to diversify my sources of income: In recent years, I have run creative workshops, with great success. Museums do contact me to assess works they receive in donations, or to act as commissioner for exhibitions or events.

Although it is a tough undertaking, the field needs new dealers.

What advice to a newcomer? The longest process is building a loyal customer base. It takes years. Establishing trust and credibility with the clientele, with the artists and institutions. The selection of works/artists gives a direction to the gallery, it is a sort of calling card. The relationship with the artists is also important: exchanges on new projects, exhibition planning, sales regulation … It’s a combination of factors that installs one’s reputation.

In Canada, interest in contemporary jewelry is growing slowly. Several customers have become collectors. Over time, however, I have had to develop a European and American clientele: By participating in various art fairs, new contacts were established. You must be very patient, and just as persevering, active, and creative as an artist.

Mike Holmes: After 25 years, running the gallery still isn’t easy, but at least I think I worry about it less. New challenges don’t seem as difficult as ones I have already survived. That must be progress! Rolling with the ups and downs of the economy and living on not very much money are the keys to keeping the doors open. My biggest ongoing challenge is the rent in a very expensive city like San Francisco. Polk Street is becoming hip, like Hayes Street before it, and the rent at the small space on the corner just went up to $13,000 a month (Lord Stanley, on 2065 Polk Street, was just named the third best new restaurant in the US…)

My advice to myself or anyone thinking about opening a gallery (there are not many new ones…) would be to be prepared for long days, hard work, and not much money, but know that the effort is repaid in huge ways with the amazing people you will meet along the way. The community of the gallery’s loyal customers, Polk Street neighbors, and my wonderful co-workers make going to work an ongoing pleasure. I love that I can go to many cities around the world and enjoy my close friendships there. Huge thanks for the support all these years.

Paul Derrez: How to survive is partly a matter of choice: Using your inherited money to invest in your business instead of buying a house. Living cheap. Building an enthusiastic team around you (assistants, bookkeeper, graphic designer, and photographer) to make running the gallery smooth, efficient, and therefore cheaper. For a while I was teaching, and this brought in some money. But it also distracted from gallery duties.

Partly it’s a matter of luck. My husband Willem had a steady job and housed and fed me when I was broke. Building up a pension was never possible for me. Happily we get a modest state pension in the Netherlands. But the gallery is always dependent on sales.

A few years ago there was the crisis, and people stopped spending money. I had to let go of my employees, but the gallery survived. Now the economy and mood are positive again, and Ra is alive and kicking.

What you need for this and other jobs are (not just a dream, but) a vision, commitment, consistency, and continuity!

Thank you!

MARQUIS IMAGE: Poster for Esther Knobel exhibition (cropped), 1995, Ra Gallery, Amsterdam, photo: Pepijn Provily

[1] Paul Derrez, in an email to the author, September 15, 2016.

[2] See Paul Derrez, Ra Gallery 40 Years Cherished (Amsterdam: Galerie Ra, 2016), 31.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid, 25.

[5] Ibid, 19.

[6] Ibid, 29.

***

インタビュー

2016年10月24日

ポール・デレ、マイク・ホームズ、ノエル・ガヨマーチに訊く

40+25+20年の戦い‐ジュエリーの世界を生き抜いて

ベンジャミン・リグネル

この10年は随所において、独立して活動するアートの実践者に混乱因子がもたらされた時代だった。文化予算の削減にともない、ジュエリーの部門や学部は経済的存続をかけて戦っている。私は、このような時勢だからこそ、経済的・政治的変動に直面しながらも、あらゆる意味で「歴史を作った」世界のジュエリーディーラーの不屈の精神を称えることは特に重要であると思う。今年、オランダとアメリカ、カナダにギャラリーを構える3人のディーラーが、それぞれの長いギャラリー史における大きな節目を迎える。私がポール・デレ、マイク・ホームズ、ノエル・ガヨマーチに異例の三者インタビューを提案したのも、ギャラリー・ラが創立40周年記念日を数週間後に控えたころで、3人はそろってこの申し出を快諾してくれた。

ポール、マイク、ノエルへ

少し前、私は『It Might Get Loud(邦題:ゲット・ラウド ジ・エッジ、ジミー・ペイジ、ジャック・ホワイト×ライフ×ギター)』という映画を見ました。ジミー・ペイジ(レッド・ツェッペリン)とジ・エッジ(U2)、ジャック・ホワイト(ホワイト・ストライプス)の個性的な3人のギタリストを追ったドキュメンタリーで、特筆すべきほどの作品ではありませんでしたが、凄技のギター演奏と、さまざまな意味で革新的なギタリスト勢の音楽史への貢献は見ものでした。当初、最年少のジャック・ホワイトは最年長のペイジをお手本にしていたそうですが、彼が聴いていた音楽の大半は、ペイジよりさらに時代を遡った、往年世代が歌う古い曲を録音したレアなカントリーブルースばかりだったそうです。ホワイトが抱く古いブルースへの憧れ(と、その粋な再解釈)は、ポールが90年代にギャラリー・ラで行った3つの展覧会について述べた「コメントや皮肉という形ではなく、歴史や遺産にかかわっていくことで、ジュエリー界を蘇らせる。彼らは、模倣に走るのではなく、大いなる感性を通して古い価値観とつながる」という一節に通じるものがあります。[1]

ポール、歴史を尊重するこのくだりは驚きです。というのも、あなたのギャラリーはまさに伝統との訣別への志向故に歴史を作ったのであり、あなたにしても、当時のオランダでは敷居が高かったものを広めるためにディーラーになったとばかり思っていたからです。

事実、3つのギャラリーが迎える節目は、皆さんが担う因習に反旗を翻す役割を浮き彫りにします。そこでまず全員にお訊きしますが、それぞれ1976年にアムステルダム、1991年にサンフランシスコ、1996年にモントリオールで開廊された当時、伝道者や歴史の作り手というご自分の役割について、どの程度自覚されていましたか?

ポール・デレ:私がオランダのジュエリーシーンに加わった1975年ごろは、ジュエリーの新時代到来という気運が感じられたものです。私たちは、歴史や慣習との訣別が必要だと考えました。新たな可能性を切り拓くためには、コンセプトやデザイン、素材、身体との関係、ジェンダーといった多くの方面での実験が必要で、その結果生まれた作品を実験的なジュエリーと呼びました。

ハイス・バッカーやエイミー・ファン・リアサムら、一部のパイオニアがこの運動の素地を固めてくれたので、私たちはそれをさらに広げ、なおかつ堅苦しさや個人主義的な面を減らそうとしたのです。

こういったジュエリーには、鑑賞者も市場もなく、戦略を練るさいは、対決や告知、啓蒙、驚き、説得の趣を感じさせるようにしました。ギャラリーという枠組みはそのための手段でした。古式蒼然としたジュエリー界を、自分たちの新たなアイデアと姿勢で塗り替えられるとすら思ったほどです。もちろんそんなのは相当にうぶな考えです。幸い、若者とはそういうものですが…

結局、歴史について記述する時は、ジュエリーという大木の芽吹き、という控えめな言い回しにとどめました。きつくて複雑な仕事でしたが長期的にみれば功を奏しました。

しかし、革命には、新たな慣習と制約が出現するリスクがつきものです。この落とし穴を回避するには、数多くの方面で新たな方向づけや調査が必要でした。伝統や、歴史的、民族的なジュエリーに(再び)つながることで、新たなインスピレーションや可能性がもたらされました。私はもう「実験的」という言葉は使いません。新しいものの「発見」というニュアンスが強すぎるのでね。いまでは新しくアイデアを練るさいは「調査」という言葉を使う方が好きです。また、過去30年の国際化もジュエリーの世界を格段に豊かなものにしました。

マイク・ホームズ:ヴェルヴェット・ダ・ヴィンチの立ち上げは遊び半分でした。多くのジュエリーギャラリーと同じく、ヴェルヴェット・ダ・ヴィンチも作り手の手で創業されました。私の従姉妹でジュエリー作家のカラ・バリアン・ベイカー(みなさんもご存じですね)と私はカリフォルニア美術工芸学校の学生で、仲間といっしょに自分たちの作品を展示する会場を探していました。当時は、1989年のロマ・プリータ地震で倒壊したサンフランシスコ中部を通る高速道路の解体作業が進行中で、本来なら放置されていたはずの近隣地域にも復興が及びました。1991年のヘイズ・バレーは空店舗が町の大半を占めており、私たちは通りの陽のあたる側に建つ、一番小さくて一番安い(月400ドル!)の店舗を借りることにしました。かくしてヴェルヴェット・ダ・ヴィンチの誕生というわけです。

そのころは、市内随一の工芸ギャラリーであるエレーヌ・ポッター・ギャラリーが、エレーヌの不幸な夭逝によって閉廊したばかりで、自分たちにも可能性があるように感じられました。また、当時のアメリカで指折りのジュエリーギャラリーといえば、ミル・バレー近郊にあるスーザン・カミンス・ギャラリーがありましたが、私たちは彼らとは違うやりかたで工芸を見せることに興味がありました。当初はジュエリーに限らず、スタジオ・ファニチャーやセラミック、コンテンポラリー・タペストリーも展示しましたが、すぐに自分たちが一番詳しいのはジュエリーであることを実感し、それからは、ジュエリーと金工作品を主に扱うようになりました。

数年以内にギャラリーは地元の作り手では足りなくなり、国内全域のアーティストの作品まで手を広げ、1996年までには英国発の新しく優れた作品群を通覧する初めての展覧会、「ブリテン・ナウ!」展を組織するに至りました。これを機に世界のジュエリーに焦点を当てた一連の展覧会が始まり、それらの展覧会やそのほかのテーマ性のある展覧会を礎にギャラリーの評判が築かれていきました。35ミリのスライドと手紙とで展覧会を組織していたそのころから、長い道のりを歩んできたものです。

ノエル・ガヨマーチ:立ち上げ当初のコンセプトは、私が好きな作品を作る数人の地元アーティストの宣伝と代表をしたいというものでした。数多くの視覚芸術のギャラリーに囲まれたダウンタウンにある文化色の強いビルの一角で、信念と熱意を胸に開廊しました。周囲にお手本となるコンテンポラリージュエリー専門のギャラリーはありませんでした。モントリオールのギャラリー・ジョセリン・ゴベイルはわずか数年間で国際的な評判を得るまでに成長しましたが、1994年に閉廊されました。私がコンテンポラリージュエリーをはじめて知った場所であるビジュー・スーク・クワンもその1年後に閉業しました。個人的な調査から、ギャラリー・ラやヘレン・ドゥルット・ギャラリーなどの世界で評判のギャラリーも知ってはいましたが、自分には縁遠い存在に思えましたし、私の望みは有名ギャラリーの運営ではなく、いまもそうしているように、ただ単にひとつの領域を守りたいということでした。

一筋縄ではいかない厳しい道のりでした。最初のギャラリーは3階で、工芸嫌いが集まるアート一色のコミュニティにあり、経済面での不安定さゆえに立ちゆかなくなりました。1999年にはそこを閉廊しましたが、その数ヵ月後に路面の空間で再開しました。この決意は報われ、開廊当初に私がキュレーションをしたいくつかの展覧会では、ジュエリーは何を表現しうるかについて、革新的な考えを提供しましたし、開廊してまもない1996年にしてすでに、国外のアーティストからの提案が舞い込み始め、ケベックにあるいくつかの美術館が、私のコレクションに興味を持ってくれるようにもなりました。

この仕事は日々の要求に追われ、自分が何を積み上げているのかに思いを巡らせてはいられませんでした。しかし、過去10年間で国境を越えて舞い込んだ数え切れない新たな提案や可能性を思うと、自分が成し遂げた成果を自覚できるというものです。私はいまもなお、この分野に貢献していると思われるアーティストの作品を選ぶことで、ひとつの領域を守り推進しようとしています。

3人には、このインタビューに先駆けて、ギャラリー史上どの展覧会が、ディーラーとしての立場を決定づけたのかをお訊きしましたが、全員から、ある立場を表明するということに深く関連する回答をいただきました。ポールは、1985年のロバート・シュミットによる、「オーナメンタム・ヒューマナム」展を挙げましたね。この展覧会は(「金への回帰」を遂げた)シュミットと、そのシュミットの動きを、新しいジュエリーが掲げる理想に反するとして猛烈に批判したハイス・バッカーとのあいだで熾烈な議論を引き起こしたことで歴史を作りました。[2] ポールは、彼がこの件でいかに強くその立場を明示したかを次のように描写しています。「私の高級志向への嫌悪感はあまりに強く、イタリアやドイツのゴールドジュエリーへの親近感は一切湧かなかった。私には作り手の立場はこうあるべきという明確な考えがあり、アーティストを奔放な天才と謳って展示台の上に祭り上げるような真似には我慢がならなかった。通常、ギャラリー・ラでは誇張は加えず、作家とその作品をその生産者と制作物であり、作家は社会と関わる職人であるとみなしていた」。[3]

いっぽうでマイクは、「反戦のメダル」展(2003-2006)が「通常は政治の話題が慎重に回避される分野で行われた政治色の強い展覧会」であるという点で、ご自分にとって決定的なプロジェクトに選ばれました。この展覧会の後には間もなく、アメリカとメキシコの国境線に目を向けた「ラ・フロンテーラ」展(2013)が開催されています。ここでは2つの点が私の興味を引きます。それは、ジュエリー界がどう「エンゲージド・アート」の制作に寄与できるかという点と、アートジュエリーの販売がある立場を取るということにどう関与しうるのかという点です。

ノエル・ガヨマーチ:私が行ってきた展覧会のなかで、もっとも意見が分かれ議論になったのは、1997年のバーバラ・スタットマンによる「損なわれたビジョン」展です。スタットマンは、伝達のオブジェであるジュエリーを通して、特定の見解を批判することを自身に許しました。彼女はメディアで使われるイメージの倒錯作用が女性の解放を阻む障害であると考え、それを、ブローチや指輪、ネックレスを使って皮肉的に表現しました。私たちが昔から女性的な手仕事や趣味と連想させて考える、テキスタイルの技術を使うことで、その姿勢が強化されています。彼女の作品を入手し装着するには、勇気と関与が必要です。なぜなら、装着者は、今日でも多々話題になる特定のタブーの主唱者となるからです。

ほかにも、過激な目的をもってジュエリーを用いたアーティストがいます。いまはもう活動していませんが、クリスチャン・ショボーは、1999年の作品で、世界規模で広がる軍拡競争や紛争の、政治面と経済面における正当化を公に批判しました。別の流れでは、アンヌ・フォトーが、ある種、現代の遺物ともいえる「ビジュー・オーティルス」シリーズ(1996-2002)で、オブジェが持つ力についての通念を検討し、社会の病魔を取り去る架空の手段として、「苦しみに効くジュエリー、希望の鍵、羞恥心をしまう容器」など、創造力あふれるスピリチュアルなジュエリーを作りました。

最近では環境問題を取り上げるのがジュエリーアーティストの間で一般的になってきていて、彼らは驚くほどさまざまな方法でこの問題に取り組んでいます。2012年にルジア・ボートがキュレーションをした「自然/人工」と題した国際展では、自然と人工の対立という概念を問うことでこの題材を捉え、人間による環境への介入の範囲を見つめました。ルジアは現状を問うアーティスト/キュレーターの良い例です。

しかし、そういった例は彼女だけではありません。ジュエリーはコミュニケーション、所属、自己同一性を体現するオブジェで、現在のやり方においては、世界や環境、自らの芸術性に対しアーティストが抱くビジョンや考察の産物となっています。私の見解では、糾弾やスローガンの手段としてジュエリーを使うのは自明のことで、ほとんどのコンテンポラリージュエリーは、ある立場を表明しています。

マイク・ホームズ:私たち3人が扱うようなジュエリーを売るギャラリーを運営するというだけでも、ひとつの立場の表明です。これだけの年月を経てもなお、大半の人は、ジュエリーは高価な素材でできた装飾品以外のものになりうるという考えを知りません。装飾品は本来価値の低い素材でも作れますし、作品のコンセプトやしっかりとした細工によって価値を得てきたという事実が、お客さんに喜んでもらえる知的興味を提供するのです。政治的な展覧会を組織するときは気を付けました。私は、特定の重要問題を矮小化しうる新たな政治的な「餌」を常時必要としているわけではありませんから。「今月の時事問題」同好会になるのは嫌です。

ギャラリーにおける私の役割は、これまでと違う完成された作品の創造の支援と奨励の場を提供することだと思います。その良い例となったのは、2011年に行った、ヴェルヴェット・ダ・ヴィンチで行ったジョー・ブロクサムのキュレーションによる「あの雲の下」展です。アイスランドのエイヤフィヤトラヨークトル火山の噴火で飛行機が欠航となり世界中の数百万もの旅行者に影響を及ぼしたさい、メキシコシティのグレイエリアシンポジウムに、世界中の多くのコンテンポラリージュエリーアーティストが集まりました。こうして多くのアーティストがメキシコで足止めを食らったことで優れた作品が誕生しました。ナンナ・メランドによる、数百機のアルミ製の飛行機で構成される「群」と題されたインスタレーションもこのプロジェクトの産物で、ミュンヘンのシュムック展を含むその後の展示会場でも大きな評判を得ました。彼女の仕事ほど有名ではないものの、ブロクサムの展覧会から生まれた優れた作品には、キャロライン・ブロードヘッドによる、一対のビーズ製ブレスレット仕立てのポートレート「キャロライン」があります。

ポール・デレ:コンテンポラリージュエリーの大部分は「装飾芸術」、つまり魅力的な造形や構造、色を持つ美しいオブジェで、服装や個性をより興味の引くものにするのに役立つものです。

花や葉っぱといった、生命や自然から直接着想を得たテーマは決して害をなすことはありません。線や面の「遊び」による抽象も同じで、どちらもあっていいのです。美意識の問題ですから。一部のアーティストはこういったテーマで見事な作品を作れますが、多くは陳腐に終わってしまいます。ジュリー・ブライフィールドやサム・ソー・ドゥオングらによる優れた作品は、ラでも誇りを持って展示しています。

一部のジュエリーは探求心と魅力があり、思いがけないテーマや造形、素材、技術を扱うか、それらを組み合わせるかしています。自信や自分の考えを持つ人に、より知的な遊びを提供しますし、会話のきっかけになることも多々あります。人から「それは何ですか?」と訊かれたときの答えだって必要です(私はときどき「きみはこれが何だと思う?」と返しています)。

対決姿勢の強いジュエリーもある。個人的、社会的、政治的タブーを取り扱う作品がそうで、コメントや批評、ときには逸脱の役割すら果たします。もっとも対決姿勢の強い種類のジュエリーはバッジです。バッジは、しばしばはっきりとした見解を示すものとして、70年代から80年代に人気があった。当時は一部のコンテンポラリージュエリーデザイナーがこの形式で遊びに興じたものだよ。マリオン・ハーブストは軍の勲章を、ハイス・バッカーは皇室ジュエリーを嘲りの対象とした。90年代になると(またも!)ハイス・バッカーが宗教とスポーツとを掛け合わせて性的志向を考察する作品を作った。それと同時期に、私自身も「顔、ペニス、十字架」と題したペニス形のペンダントシリーズを作り、ジェンダーにまつわる固定概念に揺るがし、「ピル・ルーレット・ブローチ」では、薬の治癒作用と刺激作用を問いました。

度胸のある人に限定されますが、これらの作品は会話のきっかけとしての効果が抜群ですよ!

今日では、たとえば自然や環境などを扱う、漫然とした「ソフト」な見解は見られても、鋭く明示的なものはありません。政治的正しさを求める声と意識の高まりが自己検閲を招きました。それに、アーティストにしてもそのディーラーにしても、ブローチに込めたメッセージのせいで刺されたりしたくはないですからね…

そんなわけで、私たちは装飾芸術に興じているが、それはそれで何も悪いことではありません!

ノエル・ガヨマーチ:ポール、(バッカーやハーブストといった)第3種のテーマ性のある作品や、ロバート・シュミット展を巡る白熱した議論に対するお客さんの反応はどんなものでしたか? そういう作品を買って身につけてくれました? 彼らもそういったコミュニティの中で起きた、主にそのコミュニティ自体に関する議論に関心を持ってくれましたか?

ポール・デレ:ええ、お客さんも議論に参加してくれましたし、意思表示としてそういう作品を買って身につけてくれました。

ベンジャミン・リグネル:ポールに訊きます。あまり政治色の強くない作品でも、特定の人が装着することで政治色を帯びるということはあると思いますか? 換言すれば、「政治的な付け方」というものはありますでしょうか? また、コンテンポラリージュエリーもバッジと同じくそれに適していると思いますか?

ポール・デレ:バッジやボタンは明確な(政治的)意思表示ができます。バッジひとつあれば文字やイメージを使って、共感や進言、コメントや願望を表現できます。トランプに一票を! とか、原発反対! とか、中絶の自由を! とかね。ジュエリーは、いま例示したような視覚的メッセージの役割も果たせます。装着者、状況、タイミングだってメッセージの作り手になり得ます。

マデレーン・オルブライトは、たいていはつまらないコスチュームジュエリーを使ってのことだったとはいえ、ハイレベルなやり方でこのゲームに興じましたよね。これは「政治的なつけ方」の好例です。同時代のアーティストのジュエリーを装着すること全般には政治的なメッセージはありません。唯一のメッセージといえば、この特別な作品を見てよ! これを付けていると私まで特別になれるの! っていうことぐらいで。個人的にはステレオタイプや趣味の良さを決めるルールを打ち破る、ちょっと不穏なところのある作品を付けるのが好きですが、それは政治的だとは言わないですよね。

ベンジャミン・リグネル:みなさんのギャラリーの使命のひとつは時代に伴う成長であり、社会の変化に応じて調整したり同調したりしていらっしゃいますよね。ポールは、開廊40周年記念の出版物で女性の解放について言及されていました(「幸いにも、ジュエリーの解放と女性の解放は歩調を合わせているようだ。女性の文化的・経済的自立の道が切り拓かれた。」[4])。過去10年間で起きた出来事のうち、皆さんの使命を一新させた最大の社会的変化は何でしたか? どうやってそれに対応しましたか?

マイク・ホームズ:インターネットの影響は絶大です。お客さんに接触するには一番効率のいいやり方ですが、多くのコンテンポラリージュエリーの消費を招く最たる道でもあります。フェイスブックや klimt02、Art Jewelry Forum、そして無数のウェブサイトやブログの台頭でこの分野で起きている新たな変化を知るのが容易になりました。それに、Instagramは、ほぼ一夜にして、お客さんが新しいジュエリーを知る最初の手段になりましたね。たかだか1年超で、ヴェルヴェット・ダ・ヴィンチのInstagramの投稿数はゼロから10,000近くに急上昇しました(エイミー・タバーンのおかげです!)。ふつう、こういった「いいね」の数が売り上げに直結しませんが、ありがたいことに、時にはそうなることもあります…

ノエル・ガヨマーチ:もっとも大きな変化は、オンラインのコミュニケーションとソーシャルメディアの爆発的な流入です。私たちは、こういったプラットフォームの運営方法と投稿について学ばねばなりませんでしたが、ギャラリーも作り手も、人目に触れるチャンスがいっきに増えるという見返りがありました。ときに、オンラインの情報は、作品の取捨選択という「門番」としてのギャラリーの役割を忘れさせ、絶え間のない啓蒙や自覚のキャンペーンを仕掛けます。少し例をあげただけでも、ポールやヘレン・ドゥルット、バーバラ・カートリッジ、マリアンヌ・シュロワンスキーらの、影響力のあるジュエリー専門ギャラリーのディレクター陣のおかげで、コンテンポラリージュエリーの重要なコレクターが生まれ、美術館がコンテンポラリージュエリーのコレクションを所蔵するようにもなりました。ギャラリーは、アーティストの作品に直接触れあう機会を提供する場であって、これはインターネットではなし得ません。

それでも Art Jewelry Forum や klimt02 は、啓蒙や宣伝、論議の提供や新たな客層へのコンテンポラリージュエリーの紹介という複数の次元においてめざましい仕事をしています。彼らが出す記事や出版物の適切性はこの活気ある状況を裏づけるものです。

そしていまでは、当人が望もうと望むまいと、どのディーラー(も、どのアーティスト)も、ソーシャルメディアへの投稿やウェブサイトの更新が義務になっていますし、このプラスアルファの仕事が期待されていますよね!

ポール・デレ:1976年にラ・ギャラリーを創業した当時からいまに至るまでの技術の発展にはすさまじいものがあります。ファックス、コピー機、パソコン、携帯、インターネット…旅行もずっと簡単になったし安くなりました。可能性はぐっと広がりよりよいものになりました。あとはそれをどう使うかだけです。

でも、ギャラリーの経営について言えば、多くの面で昔のままです。開廊時間を厳守し、興味を引く品ぞろえにして、作品に合ったディスプレイを整えて、お客さんに愛想よくして、情報提供して、サービスして。成功の秘訣は、肉屋のそれと基本的にはいっしょです。ジュエリーを家業とする家に育ったので、基本が遺伝子レベルで組み込まれているのです。僕は、初志貫徹と継続の力を信じています。(数年前、リートフェルト・アカデミーで職務的実践を学生に教えていたけど期間限定店舗形式の人気がすごくて参りました!)

『Ra Gallery 40 Years Cherished』の上梓に向けてギャラリー・ラの物語を執筆していたら、これまでの首尾一貫した姿勢に気づいて自分でも驚きました。

そして、お客さんの変わらぬ姿勢にも。彼らは比較的少人数で、知性や美、手仕事による魅力と説得力のある作品を求める人たちです。私のギャラリーオーナーとして果たせる役割なんて、よき仲介者であることぐらいです。

ベンジャミン・リグネル:私たちは、ディーラーもまたアーティストと同様、ギャラリーの存続のために戦わねばならず、助成金や州の財政措置(ポール、たとえば、オランダ人作家の作品購入時に適用されたかつての15パーセントの割引制度は、オランダ人作家に限らず適用される利子の無料化という措置に改正されましたね[5])、クライアントや評論家上がりの後援者からの支援…そして姿は見えずとも不可欠なパートナーによる協力という、さまざまな形における大きな支援体系が整わずしてはその戦いがなし得ないことも多いのだという事実をしばしば忘れがちです。(再度ポールを引き合いに出させてもらうと、ビーゼルシュトラートへの移転の翌年は「安定した職を持つ夫のおかげできつい時期を乗り切れた」とおっしゃっていますね[6])。そこで、ギャラリー稼業の不安定さと、どのようにしてこうも長く続けてこられたのかをお聞かせいただけますか? この仕事ならではのチャンスについてもお話ください。若いころの自分にアドバイスを送るとしたら、どんなことをすすめますか?

ノエル・ガヨマーチ:最初のころは、ギャラリーを続けていくために副業を持っていました。重労働でしたが、熱意と忍耐で乗り切りました。2001年に収益が出るようになり自治体の支援を受けられるようになりました。いくつかの展覧会では、主にケベックの作家の振興になるからという理由で文化機関による財政支援を受けられました。

それでもいまだにきつい時期もあります。ポールと同様、ギャラリー創業当初は、励ましや、パートナーからのサポートが欠かせませんでした。(2012年に彼がモントリオール・ジュエリースクールの校長に就任してからというもの、ディーラーの重要性をますます強く実感してくれるようになりました)。

また、さまざまな収入源を確保するよう心がけてもきました。近年はワークショップの運営が大きく実を結んでいます。美術館から寄贈品の査定を頼まれたり、展覧会やイベントのコミッショナーをやったりもしています。

きつい仕事ではありますが、この分野は新しいディーラーを必要としています。

新しい人たちにアドバイスするとしたら、いちばん時間がかかるのは、贔屓にしてくれる顧客基盤の構築だということです。これには何年もかかります。お客さんやアーティスト、組織との信頼関係を築くのはね。ギャラリーの方向性は、どの作品やアーティストを選ぶかで決まるもので、それがある種名刺代わりになります。新しいプロジェクトや展覧会の企画、売買の取り決めについて話し合ったり、アーティストとの関係も大事です。評判とは、さまざまな要因が絡み合って築かれるものです。

カナダでは徐々にコンテンポラリージュエリーへの関心が高まりつつあります。何人かのお客さんは今ではコレクターになってくれました。しかし、ヨーロッパやアメリカでの顧客づくりも必要で、これまでさまざまなアートフェアに参加して新しい人間関係を作ってきました。たいへんな根気が必要ですし、アーティストと同じぐらいのべらぼうな粘り強さと行動力、創造性がなくてはなりません。

マイク・ホームズ:25年という年月を経てもなお、ギャラリー経営は楽な稼業ではありませんが、少なくとも悩みは減ったと思います。新たな挑戦が訪れても、いままでのものに比べればたいして困難には思えません。これは間違いなく進歩ですよね! 経済変動の波に乗り、潤沢とは言えないお金で生活することが、ギャラリー継続のカギです。私にとって目下の最大の課題は、サンフランシスコのような街は、賃料がバカ高いということ。ポルクストリートもかつてのヘイズストリートのようにヒップになってきたから、角地の小さなスペースでも月の賃料が13,000ドルにまではね上がってしまってね(つい最近、ポルクストリート2065番地のロードスタンレーはアメリカで新規開店されたレストランのベストスリーに格付けされてしまったし…)

自分自身や、ギャラリーを始めようと考えている人たちへのアドバイスは、先は長く、仕事はきつく身入りは少ない生活を覚悟して臨むこと。でも、その途上で出会うすばらしい人たちによって、その苦労は大いに報われるという点はわかってほしい。贔屓客のコミュニティ、ポルクストリートのご近所づきあい、すばらしい同業者のおかげで、いつまでも仕事に行くのが楽しく感じられます。世界の多くの都市に足を運べて、行く先々で親しい友人と親睦を深められるのは、なんともうれしいことです。長年の支援には深い感謝を感じます。

ポール:存続の問題は取捨選択の問題でもあります。遺産が入ったらマイホームの購入ではなく事業に投資するとかね。生活費をかけないこと。ギャラリーをスムーズに効率的に、その結果としてお金をかけずに回していくには、熱意あるチーム(助手、帳簿係、グラフィックデザイナー、写真家)を作ることです。一時は教職で収入の足しにしていたが、それだってギャラリーの業務に注げるはずの集中力を殺いでしまいます。

運だってものを言いますよ。僕がダメな時期は、定職をもつ夫が僕を養ってくれた。僕の力じゃとうていペンションなんて建てられないですよ。僕らは運よくオランダに状態のいいペンションを買えたんです。でも、ギャラリーは常に売上にかかっているものだよ。

数年前に経済危機があって、人々がお金を使わなくなってしまいました。僕も従業員を手放さなければならなりませんでしたが、ギャラリーは残りました。いまは経済も世間のムードも明るさを取り戻して、ラも健在です。

この仕事にしてもそれ以外の仕事にしても、必要なのは(夢を持つだけじゃなく)ビジョンと努力、初志貫徹、継続ですよ!

ありがとうございました!

[1] 2016年9月15日に筆者宛に送られたポール・デレからのメール

[2] ポール・デレ著Ra Gallery 40 Years Cherished (Amsterdam: Galerie Ra, 2016)、31頁参照。

[3] 同書参照。

[4] 同書25頁参照。

[5] 同書19頁参照。

ベンジャミン・リグネル:デザイナー、ライター、キュレーター。学士過程で美術史、修士課程で家具デザインを学び、修士号を取得した直後にジュエリーデザインの道に進む。2007年、ジュエリーの研究と振興を目的としたフランスの団体、ジュエリー保証協会(la garantie, association pour le bijou)を共同設立。2009年、欧州応用芸術イニシアチブ、シンクタンクに加入。2013年、ミュンヘン国立造形美術大学(ニュルンベルグ、ドイツ)のゲスト講師を務め、同年1月、アートジュエリーフォーラムの編集者に任命される。2015年、ジュエリーの展覧会を考察した初の著作『Shows and Tales』の編集に携わる。

Translated from English by Makiko Akiyama.