Bonnie Levine: After a rich and varied career in politics and administration in Sweden, you’re now focusing your energy on promoting Swedish art and design, including contemporary art jewelry, which you also collect. How and why did that transition happen? What kinds of activities or projects are you involved in?

Inger Wästberg: In 1999, my husband was appointed Swedish Consul General to New York. That means representing and promoting your country. Fostering a positive image of a nation is as important as furthering its political agenda. Our mission was to promote Sweden as a state-of-the-art country. The residence where Consul Generals have lived since 1946, the 1910 Beaux Arts building at Park Avenue, was filled with dreary furniture and Persian rugs. I wanted the house to be a contemporary meeting place that could accommodate all sorts of events, from bestowal of a royal medal to fashion shows, seminars, and formal dinners. I wanted to feature the latest, brightest talents, especially young female designers.

Students at Stockholm´s Konstfack Art and Design School were involved in the transformation and redecoration. Around 5,000 guests, mostly Americans, attended events at our home each year, which gave a great opportunity to wear contemporary art jewelry—an excellent way to facilitate communication!

During most of 2017, the exhibition Transformations—Six Artists from Sweden (which was curated for Venice Municipal Museums and Nationalmuseum in Stockholm) has been at Palazzo Mocenigo in Venice. The exhibition can be seen as a contribution to an ongoing discussion of definitions and boundaries.

A summary of the contributions of these artists is that they have raised the art of jewelry from a craft to an art. Contemporary art jewelry is still beautiful but it is often also reflective, unconventional, and born of ideas. One may ask if jewelry is art or craft but one may also wonder whether this question is relevant at all. The fact that the exhibition is shown in conjunction with the Venice Biennale indicates my stance.

During the fall, I will continue to mentor younger women in their mid-careers and continue to give lectures about contemporary jewelry. I’m also in dialogue about some future projects.

Much in the way that you seek to promote the jewelry of your homeland, Cristina Filipe—winner of the 2018 Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant—is using her grant to bring international attention to Portuguese jewelry. Given your experiences in Sweden, what advice would you give her?

Inger Wästberg: It’s a really difficult question; there are no easy ways. Every country is different, but you also have to act and observe in the international context, as well as attend and participate in seminars and exhibitions in order to pick up influences as well as to influence. You must also use your own networks and see what you can build on. You should try to use the international connections at national arts institutions and also diplomatic representations abroad.

Last year you were instrumental in the exhibition Open Space—Mind Maps: Positions in Contemporary Jewelry, at the Nationalmuseum in Sweden, a sequel to a show staged 30 years ago. Tell us about that show and your role in making it happen. Did it accomplish what you’d hoped?

Inger Wästberg: The exhibition was intended to show art in jewelry and how jewelry acts as artistic field research, participating in the current topics of art in our time—an aesthetic discourse and artistic position that reacts to life events, personal history, nomadism, image, and memory.

It featured 30 artists with 160 works. The selection of artists covered those working in the foremost academies and universities in the field of jewelry, among them Sophie Hanagarth, who teaches in Strasbourg; Karen Pontoppidan, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich; Miro Sazdic, at Ädellab at Konstfack in Stockholm; Suska Mackert, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Nuremberg; and Mikiko Minewaki, at the Hiko Mizuno College in Tokyo. Their work demonstrates the strong impact of female artists, who have provided a paradigm shift in style, thematic issues, and the appearance of jewelry today. This was also one of the reasons why the exhibition had a special focus on gender positions and gender shifts.

I initiated the exhibition with a written proposal to Berndt Arell, director general at the Nationalmuseum. He was interested and accepted the idea. I realized he didn’t know anything about contemporary art jewelry, so I suggested a visit to Schmuck in Munich and a meeting there with AJF. In the exhibition catalog, he writes, “Meetings, conversations, visits to exhibitions, studios, and artists in her company slowly revealed a scene, or an entire world, that I had never seen before, never been open to, never known about. This is a category of artists who work, as it were, alongside the contemporary art scene. Many of them went to the same colleges as other artists and yet they appear to be oddly excluded.”

The exhibition was not the only event happening at that time. I initiated a meeting with other participants in the art scene, and, inspired by Schmuck, five other museums, galleries, and artist organizations took part in Stockholm Art Jewelry Spring 2016—in all 21 different venues. The project was a great success, with good media coverage.

You recently curated an exhibition of Swedish jewelers, at Reinstein|Ross Gallery in New York City, called Breakthrough. What was the focus of this show, and how/why did you select the particular participants that exhibited?

Inger Wästberg: Their work is far from what is perceived as typically Swedish—silver based on abstract forms. But they link contemporary jewelry to the rich heritage of work in silver. Their objects are beautiful and unconventional, very wearable, and with strong references to traditional jewelry.

I think their relation to goldsmithing is relevant. Ingrid Bärndal works with traditional goldsmithing techniques and says, “the things I can achieve with polypropylene I cannot do with metal.” For Agnieszka Knap, art jewelry is closely related to goldsmith craft and ancient techniques such as enameling. Åsa Lockner starts with traditional materials and shapes, but stretches the boundaries of how material is perceived. She has clear references to classic jewelry. Hedvig Westermark is an educated goldsmith and has for over 20 years developed her art by returning to recognizable shapes. Jelizaveta Suska learned classical techniques in Latvia. She uses polymer covered with crusted marble and creates an illusion of solid stone. For the rear and supporting details she uses valuable metals like gold, titanium, and silver. She has interesting mind maps to show.

In terms of your own collection, I understand it’s primarily Swedish jewelry. Beyond that, does your collection have a particular focus, and do you have plans to broaden it? Why or why not?

Inger Wästberg: My personal taste determines the selection. I never planned to make a collection, so I had no strategy. The intention was to wear it myself.

The Swedish tradition of working with silver is strong. The oldest known silver mine dates back to 1360. My first group of jewelry came from Nutida Svenskt Silver (a cooperative of artists) and LOD, a group of seven silver and metal artists who share a combined studio and gallery in Stockholm to keep silver production alive.

My preference is for works that mirror political and societal issues. I have had a focus on gender issues, sustainability, nomadism, and of course jewelry with historical references. That means jewelry that often challenges the conventional notion of what is beautiful and reaches beyond decoration with conceptual qualities. Here are some examples:

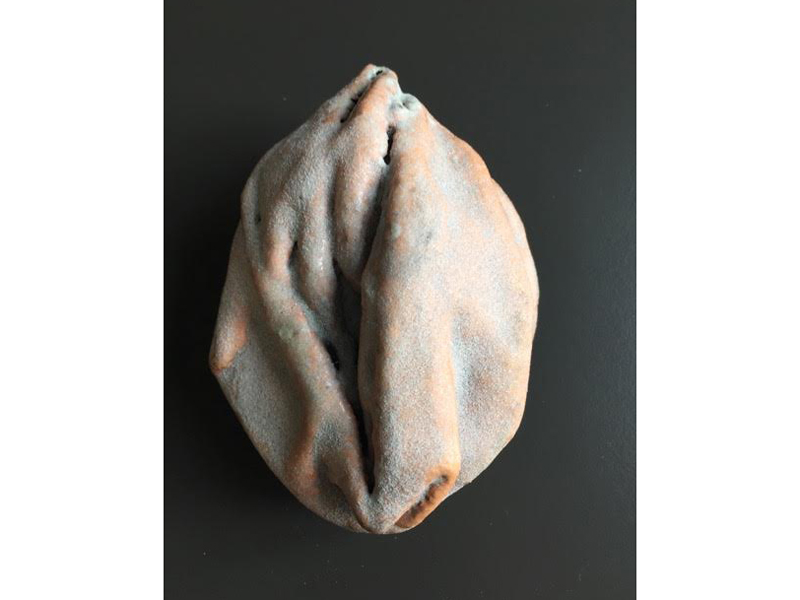

Carolina Gimeno recognizes herself as a Latin American jeweler educated in Europe. She has been collecting socks to work with, a material that comes from both women and men, not being gender specific. By transforming these into vaginas, she is seeing how this could lead to discussions. Now it associates to Donald Trump’s pussy grabbing.

Tobias Alm wishes to challenge and question the culture of masculinity that surrounds him and to contribute to an analysis and reformation of gender structures.

The most recent piece I’ve acquired is a work by Xiaodai Huang. She elaborates on the influence industrial production imposes on biological features. Her inspiration comes from the Fukushima nuclear explosion.

The war in Syria is reflected in this work by Sofia Zarari Antilogos, who lived on Lesbos when the big influx of Syrian refuges occurred.

Later this fall, you’re going to be one of the jurors for the 2018 AJF Artist Award. What are you looking forward to in this experience? As a collector, what do you feel you can contribute to the process?

Inger Wästberg: It will be scary and difficult to judge online without being able to touch and handle the objects and see their scale. I’ve had the opportunity to spend plenty of time visiting many exhibitions in different places, and hope to take part in discovering new talent and new developments.

As a collector, what advice would you give to emerging artists just starting their studio practice?

Inger Wästberg: Don’t be shy! Try to identify collectors and contact them and invite them to come and visit. You must have business cards to hand out. It’s extremely important to have good photos of your work and a good website.

Is there anything particularly exciting you’ve seen, heard, or read lately that you’d like to share?

Inger Wästberg: Congratulations to Anne Dressen, the curator of the exhibition MEDUSA, at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. Organizing a jewelry exhibition in a modern art museum is a fantastic event, as jewelry is often an art-world taboo. Everyone interested in this field should try to visit that exhibit or buy the catalog. On loan to the exhibition is my favorite brooch, by Hanna Hedman.

Thank you, Inger! I’m looking forward to working with you on the 2018 Artist Award!