You don’t have to fly into space to reach the stars. It happens when you win the Herbert Hofmann Prize! It’s among the most prestigious awards in the field of contemporary jewelry.

We interview the three winners of the Herbert Hofmann Prize 2024—Azin Soltani, Empar Juanes Sanchis, and Takayoshi Terajima—about their creative approaches, sources of inspiration, and the works that were awarded.

- They represent three different countries and cultures, and three completely different approaches toward jewelry

- Azin Soltani (from Iran) re-creates in jewelry the images of homes from her homeland, down to the last brick

- Empar Juanes Sanchis (Spain) left behind a successful career in architecture to devote herself to jewelry making and creating musical-jewelry performances

- Takayoshi Terajima (Japan) found inspiration in the constraints of the pandemic and combines AI and Japanese traditional crafts

Azin Soltani’s Jewelry Resembles Traditional Iranian Houses

Elena Karpilova: Tell us about your background.

Azin Soltani: I studied industrial management both for my bachelor’s degree in Iran and my master’s degree from a consortium of three universities (Politecnica de Madrid, in Spain; Politecnico di Milano, Italy; and KTH, Sweden). I also tried to study physics for my second bachelor’s degree, in South Korea. I thought I could become an astronaut!

My jewelry-related story started in 2010 in a small silver shop behind the university in Seoul. One day I entered and simply asked if they also taught how to make jewelry, and that was it. For about two to three months, I attended classes there. And here I am, a goldsmith, lapidarist, and trying-to-be-an artist.

Tell us about your work.

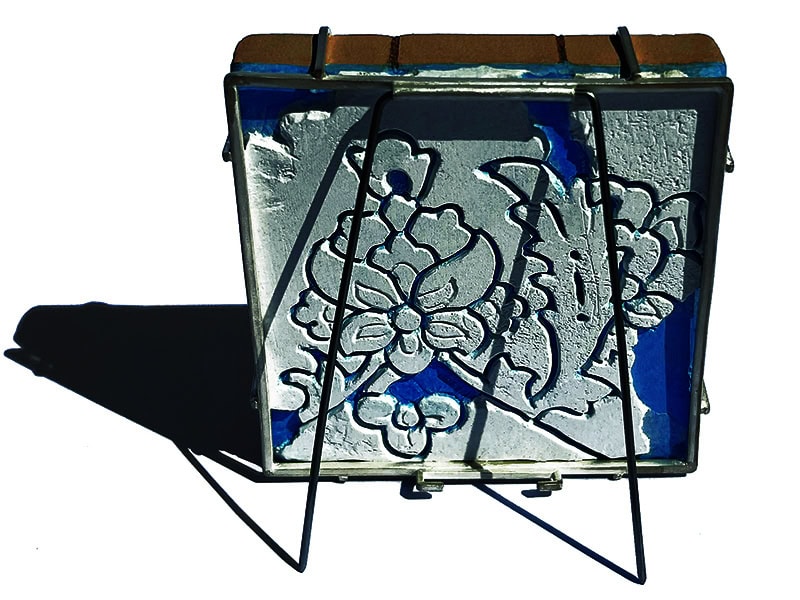

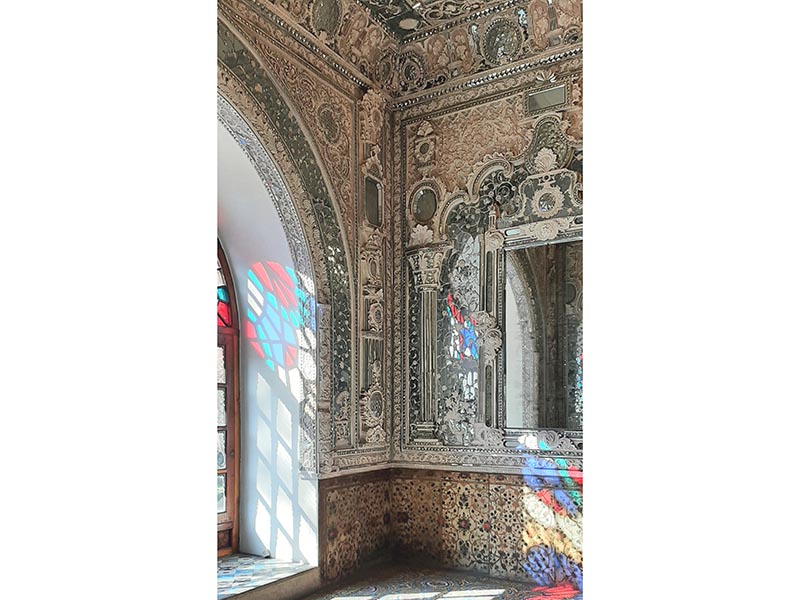

Azin Soltani: The idea behind the works titled Inside and Outside comes from the traditional architecture of Iranian houses. They are made of brick tessellations on the exterior, and plaster, layers and layers of it, on the interior. The walls have murals, mirrors, and other delicate details on them. You see the handmade plaster and mirror decorations inside the houses if you are invited and allowed to go inside.

It’s all attractive, all durable and weather-resistant for hundreds of years. But they will eventually fall into ruin or at least partial disrepair no matter how hard you try to avoid it. For me, houses are humans. What happens in those houses is living. As nothing can remain intact in the claws of time, eventually comes ruin, which is death.

The “walls” of my pieces have been made exactly the way workers build them. I got the tiny bricks from a private supplier. It produces them for students who study traditional architecture in Iran, to make maquettes of old and historical buildings or for their practice. Sometimes I broke them and modified their sizes to make my own pieces. Ancient Iranian stucco and mirrorwork (Ayeneh-kari) have been applied to decorate the internal parts. I have mostly employed techniques, methods, and patterns practiced about 500 years ago in the Safavid dynasty.

Who inspires you? To whom are you grateful?

Azin Soltani: Whoever I am, whatever I have achieved, is touched by the presence of my family and their unconditional support. They never got disappointed with me. Whenever I got tired of continuing, they stayed with me and pushed me forward.

Empar Juanes Sanchis’s Jewelry Practice Inspired a Musical Performance

Tell us a little about yourself.

Empar Juanes Sanchis: My story is a story of searching. I come from a humble family in a town of 1,300 inhabitants near Valencia, Spain. Art isn’t a priority there. My father painted as a hobby. He was the one who first introduced me to art, when I was a child. Nonetheless, for my whole family, responsibility and building a profitable career with a stable income are the most important things. I probably chose architecture because it was somewhat expected of me.

I completed my architectural degree between Valencia, Aachen, and Beijing. I had a job many colleagues from university would dream of, and felt respected, but I needed something more. I felt the need to work with my hands and sought more creative freedom. I looked into different art universities. Maastricht was perfect for me, as it greatly helped me find the experimentation and creative freedom I longed for. But it was during my exchange in Idar-Oberstein that my soul was stirred. There I discovered my fascination with stone and found my place as a jewelry artist.

How did architecture influence your approach to jewelry?

Empar Juanes Sanchis: Studying architecture has helped me not only formally, with a highly developed spatial and volumetric vision, but also in my capacity for work and perseverance, which are necessary in a career as demanding as architecture. Sometimes when working with agate I had to open many raw stones to find one big enough, uniform, and with an absence of veins, inclusions, or fractures. I needed to be able to cut it thinly and precisely, down to the millimeter, without breaking it.

Stone is a very special material for me, but it’s just a medium. What’s important is expressing my inner world. Apart from jewelry, I play cello. I’m interested in photography, too. Last year, during Melting Point, I conceptually accompanied my pieces with photography and a sound performance. I improvised with my friend Amadeo Moscardó around the concept of tension, using synthesizers and my cello connected to pedals, amplifiers, and a stone-cutting saw. We divided the performance into three parts, related to three of my pieces. One of them was the brooch Don’t Dare, which won the Herbert Hofmann Prize.

My background in architecture also influences how I understand jewelry. I like to question the boundaries between jewelry and object. I love contemporary jewelry because of its scale, its freedom, its self-expression, its intimacy … not because of its ability to be worn. I define my jewelry as sculptures that can be worn, but not necessarily. It’s a pity that certain competitions only allow wearable pieces. I hope curators, gallery owners, and institutions become more open in this matter because I believe that contemporary jewelry goes far beyond its wearability.

What’s the idea behind the piece that won the prize, its story?

Empar Juanes Sanchis: I’m fascinated by pushing the limits of the stone. My work with stone focuses on strength, tension, and volatility, where risk-taking is essential.

This piece arises from three parallel studies: one formal, studying the geometry of the circle; another material, constantly pushing the boundaries of stone; and another emotional, reflecting on personal space and our fragility as human beings.

The real challenge for me lies in finding an emotional connection through abstraction, through minimalism, and I believe I managed to bring these qualities together. Initiating a strong, direct, wordless dialogue between the wearer and the observer, Don’t Dare is a tribute to both fragility and life.

To whom are you grateful?

Empar Juanes Sanchis: I am grateful that I was brave enough to give myself the opportunity to search and keep searching. I also appreciate my time in Idar-Oberstein for helping me find my path and place as an artist, and above all, I am grateful to the people who believed in me. They helped me stay afloat in moments of great insecurity or uncertainty.

Takayoshi Terajima Engraves AI-Generated Portraits

Tell us about your jewelry.

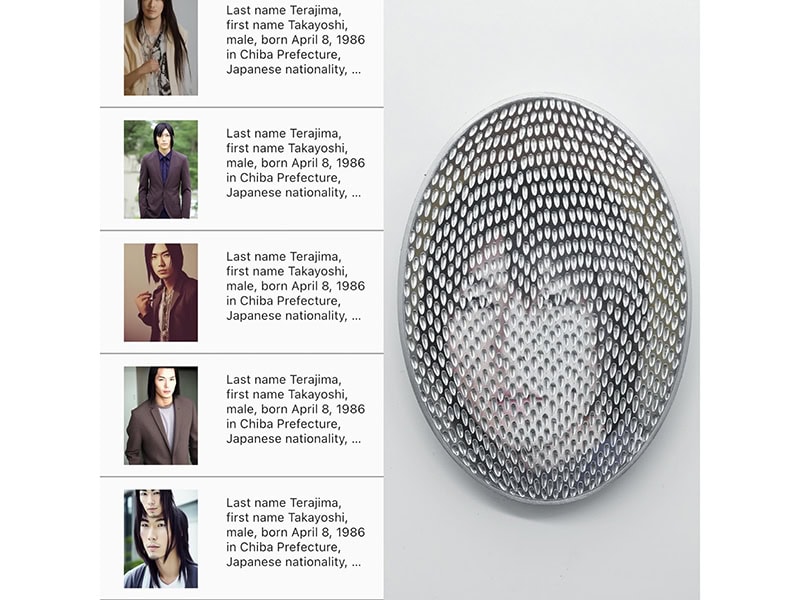

Takayoshi Terajima: My AI project started around the time the Corona pandemic began. When the need for jewelry began to be questioned, I was intrigued by the information on the screens of Zoom meetings. This information was a person’s personal belongings, such as bookshelves, houseplants, curtains, posters, etc. Everything on the screen, including the person’s image, is processed as the same two-dimensional image.

Therefore, I consider the screen as an extended space of the body, and I began to create two-dimensional works as jewelry to be “worn” on the screen. The first works were simple metal works, but in order to enhance the affinity with the digital space, I changed the production process by converting the metal into data and then outputting it again as a material.

The pandemic came to an end. This meant a recursion from digital space to real space. I began to think of jewelry that could be worn on the human body again. At the same time, I began to video call more frequently with my family in Japan. This gave me more time to reflect on my roots. My family has lived on the same land and grown rice for about 300 years. Since I have only Japanese citizenship, I have to apply for a visa [to live] in Germany. I have to submit many documents every year. I realized that this character information is my identity in this land. So I was interested in what would happen if I let AI draw my portrait using this textual information.

I put in AI not only my name and birthday, but also my family structure, religion, nationality, and much more information. It is taboo to enter personal information into AI. And I may be an idiot for repeating it every day. But as an artist, I couldn’t resist the urge to say, “I really want to use this information!” So I have no regrets.

The engraving technique I use, like rice cultivation, is a wonderful traditional process with a long history. By combining the latest technology with traditional craftsmanship, I have succeeded in creating a fascinating effect on the surface of the piece. And this effect is maximized when worn. As the wearer moves, the light reflects off the surface of the piece, causing various changes to appear.

Engraving is done with a chisel made from a carbon steel rod and a small hammer. The Japanese style is to engrave grooves by pointing the chisel toward oneself. Since the thickness of the plate is only 0.3 mm, I made my own chisel by trial and error to find a shape that is wide enough without being too deep. In Japanese traditional craft, it is common to modify tools by oneself. I have made more than 100 chisels so far. I am always conscious of a certain amount of force and the angle, and engrave in a way that my body learns, just like training for sports. I have been playing volleyball for more than 20 years, so engraving and volleyball training are linked in my mind.

Who are you grateful for?

Takayoshi Terajima: There are so many people I would like to thank. It is difficult for me to choose just one. If I had to focus on one person, it would be my wife. She is a ceramic artist. We have been together since we were university students in Tokyo, so she has watched my struggles for almost 15 years. We often talk about our artwork. We are fortunate to have people nearby with whom we can discuss things in depth.[1]

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] Takayoshi’s answers, like all the text in this article, were edited prior to publication. Among the changes, Takayoshi’s final paragraph was deleted. It said, “Finally, this text was translated using Google Translate, DeepL, and Chat GPT. So please forgive me if the sentences are unnatural. This is what I and AI are capable of at present. I would like to express my hope and appreciation for the future development of technology.” Elena Karpilova, the author of this article, finds it noteworthy that Takayoshi does not hide these AI tools that we all use, often masking our own lack of knowledge. Karpilova argues Takayoshi is expressing that he doesn’t know everything, can’t know everything. “Takayoshi takes AI as a co-author for the interview, respecting the intellectual property rights of AI,” says Karpilova, “and mentions it not as a ‘crutch’ but as a full-fledged partner in creating the text. He uses the same approach in jewelry-making, paying tribute to modern technologies.”