Diane Azzam: I left the Middle East twice. The first time, in 1967, I followed my parents, who had decided to leave. It was just after the Six-Day War between Israel and the Arab states. We were living in Lebanon and the political situation was beginning to get tense. So my father, who worked in the Swiss watch industry representing Swiss brands in the Middle East, preferred to be based in Geneva with his family. That’s when I decided to start my jewelry studies at what was then called École des Arts Décoratifs de Genève and is now Haute École d’Art et de Design (HEAD). I decided to go back to Lebanon in 1977, at the beginning of the Lebanese civil war, with my first husband, who is Lebanese. Being there during that time was difficult for me, so I left the Middle East once again.

Why did you decide to become a jewelry artist?

Diane Azzam: Thanks to my father’s work, from a very young age I was able to admire collections of watches of the brands that were most prestigious at that time. No doubt that influenced my career choice. I was also attracted to fine arts and in particular to 3D work. I saw jewelry as miniature sculpture.

Diane Azzam: It’s often said that teaching is an enriching experience for professors. I personally agree with this point of view. I’m always surprised by the high quality of my students’ creations, as well as the creativity, diversity, and freshness that reside in their work.

How do the vagaries of everyday life inform your teaching?

Diane Azzam: If I’ve understood your question correctly, you are referring to the ups and downs of everyday life as they relate to teaching—right? Teaching an art that has a strong emphasis on technical skills means that I have to adapt myself to each student specifically, to their requests and expectations, as well as the problems that come up when creating each piece. It is very informative pedagogical “gymnastics.”

Diane Azzam: Hard to summarize why this theme is close to my heart. I had the opportunity to do one year of advanced studies within the Centre de Formation pour la Céramique Contemporaine (CERCCO, or Experimentation and Research Centre for Contemporary Ceramics), which is part of the Geneva University of Art and Design, where I teach. To be accepted into the program, I had to present a theme that would be the subject of my diploma work and could be developed throughout the year. This program had a strong fine arts bent to it; I did it because I wanted to get out of the cramped box that I sometimes find myself in as a jeweler. I was also looking to refresh myself artistically by becoming a student again.

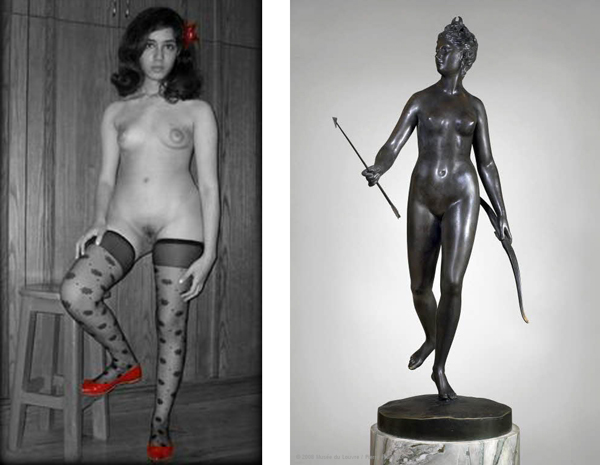

This coincided with the Arab Spring, also called the Jasmine Revolution. It was incredible what was happening in the Middle East. There were young men and women gathering in the streets, claiming their rights and liberties. It was the beginning of a peaceful revolution in which women played active roles. There was a young Egyptian woman who posed nude for the camera and circulated the photo in the media, courageously announcing “my body belongs to me,” and that really made an impression on me.

This time of public euphoria brought attention to the energy of the Arab world. From near and far, we could only feel solidarity with them. Then came the postrevolution disenchantment. The gates of hope slammed shut, the horizon dimmed and was enshrouded, and so were the bodies of women. The subject of my diploma was born out of this disillusionment.

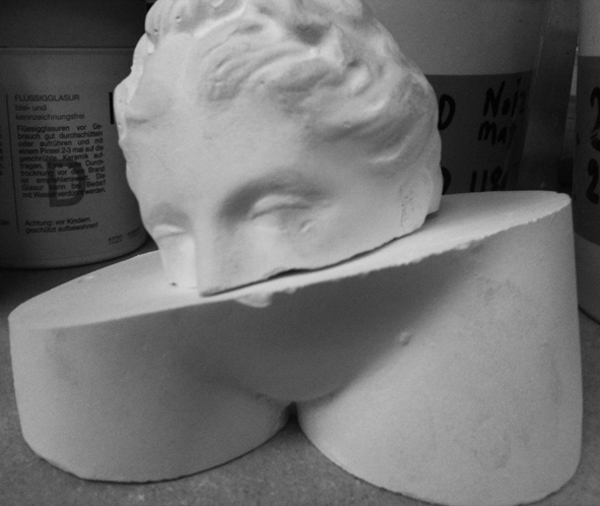

Diane Azzam: This is a story within a story. It all started off very differently from the final result. Certain circumstances led me to create a mold of the statuette Diana the Huntress, which was a miniature replica of one of Jean-Antoine Houdon’s[1] pieces. This statuette, by total chance, was perched right in the middle of the atelier at CERCCO.

It had actually been cast there when that space was a renowned casting center and ended up staying there in its perfect nudity, as the only vestige and witness to the past. I found this intriguing and funny and, at first, I identified with it, and then I thought, intuitively, that it would help me to get to the heart of my story. From the mold, I reproduced my replica by playing with its shapes at will, by disfiguring, dismembering, dismantling, and restructuring. I wanted to know more about the circumstances of the creation of this work. What I learned took me straight to my subject.

“The Diane of Houdon,” created just before the French Revolution, was considered scandalous at that time because it was naked, with a lightly suggested sex. (In Roman mythology, Diana is a modest goddess, never shown undressed.) A short time after the Napoleonic period, in order to be displayed in the Louvre, the censors decided that the sex of the bronze version of Houdon’s work be covered with a sheet of bronze attached to the statue with threaded bars. It is on display in the Louvre to this day, in this subtly mutilated state.

The singular history of this piece of work helped me to see a connection between these two periods of History, with a capital H: the French Revolution and the Jasmine Revolution with their similar circumstances—the simmering, bubbling ideas, and a similar desire for political change that could have led to an evolution of archaic traditions.

In both cases, there was a postrevolution backlash resulting in increased conservatism, with strict policies imposed on women in a repressive way.

Following my discovery about the genesis of this statue, I decided to make—for my replica—a small piece of jewelry in the form of a G-string, or a “hide-a-sex,” taking my inspiration from the fig leaf, an emblematic symbol of modesty. I placed it on the statuette’s face and mons pubis. My statuette was then strangely dressed because despite everything she was still, curiously, naked. To the questions, What do we show? What do we hide?, I didn’t have an answer, but questions. Aesthetic solutions arose. It became clear to me to develop forms similar to this piece of jewelry—the “hide-a-sex” and “hide-a-face”—into hypertrophied jewelry that became these sorts of metallic bas-reliefs.

There is a paradoxical quality in your brooches: The eloquence of hard edges draws attention to the object that—once worn—becomes fluid and transformative. Are you trying to embrace a dichotomy between the politics of covering and revealing?

Diane Azzam: There is no dichotomy between covering or exposing the body of a woman, they are two sides of the same cultural coin. If the notion of modesty didn’t exist, there would be no more need to cover up or reveal. Throughout the history of art, representations of women entirely nude were always considered shameful.

Complete nudity of the woman’s body was always regarded as shameful, hypocritically tolerated and morally reproved. Throughout the history of Western art, censorship required artists to cover up or carefully eliminate what was judged indecent.

In the art of the Islamic tradition, censorship in this regard was even more virulent, and that encouraged the development of an ornamental style of great beauty. From the perspective of dress customs, the veil puts a limit between what should be seen or hidden. In this sense it works in my opinion as full coverage and total prohibition.

I found similar geometric shapes in your origami rings. I see this as a reduction that evokes rigidness and constraint. How do you explain this penchant for geometry, in such diverse works?

Diane Azzam: I was always fascinated by the geometric complexity of Islamic arabesques. Even before being able to draw or endlessly duplicate them thanks to Illustrator, I had a book that provided step-by-step instructions for building them and I spent hours on them with the help of a compass, square, and ruler.

Like Monika Brugger’s jewelry and installation, your series seems to deconstruct, manipulate, and exalt the friction of touch, gaze, and intimacy. What sort of encounter did you want to encourage between your work and the audience?

Diane Azzam: Monika Brugger’s jewelry is in certain cases suggestive of lace. These pieces are airy and let light pass through. I created my pieces to be airtight so that the identity, warmth, and personality in the eyes of the person who is wearing them cannot pass through. It is said that eyes are the mirror of the soul. Maybe this is one of the reasons women are obliged to cover their faces. Men could see this as dangerous, something in which they could lose themselves. I could have played with the reference to the moucharabieh (or see-through wooden latticework), which is also a kind of Arabic lace. On the contrary, I decided to conceive my masks to be impenetrable and not let the identity, intimacy, and intensity of the person’s glance filter through.

A new generation of Middle Eastern makers is taking root in the West, centering their practices around politics of gender, spaces, and religion. Where do you think that your work and background aligns with this?

Diane Azzam: Without by any means comparing myself to them, I have a lot of admiration for artists such as Adel Abdessemed, Kader Attia, and Mona Hattoum. My big hope in doing this work was, as I said earlier, to get out of the sometimes-restrictive box I sometimes find myself in as a jeweler in order to take a step toward sculpture. I am still very much a jeweler in my way of creating and thinking. It’s just that I come from the Middle East and what happens there affects me. As a woman, I’m from the generation who experienced the women’s liberation movement and read The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir. Seeing our liberties taken away and a return to wearing the veil concerns me a lot. This is what I wanted to bear witness to.

Photography gives your work a public, mobile quality that the jewelry objects do not have. Is the “work” more about photographs of veiled woman or the jewelry pieces themselves?

Diane Azzam: The photos that I have done for this specific work, showing a woman wearing the veil and the jewelry over it, appear to give weight and an extra meaning to my pieces. I think the two things, the jewels and the photos, could stand alone, but they go together and complement each other well.

Diane Azzam: It’s a flower bed of a thousand jasmine flowers made of white porcelain that I made in homage to the Arab Spring, to this extraordinary moment of euphoria, to the birth of all of the hopes and ideals, and in doing so, I only wanted to emphasize the idea of whiteness, abundance, and freshness that was supposed to symbolize the movement in the beginning.

What kinds of people have seen both these series? How does your Western audience connect to a work that is so culturally specific and how do you make use of their reaction?

Diane Azzam: At the moment, my audience is rather restricted. I’ve had feedback mostly from people in my inner circle who appreciated the finished work. During the creative process I was challenged by some of my professors who didn’t see much point in digging into such a politically charged theme. That’s when I had to hold fast and carry on to prove myself. I have to admit that it wasn’t easy. I had to dig deeper into my subject to get answers that I personally find acceptable and meaningful.

One last question: What are you repulsed by? What attracts you?

Diane Azzam: Music, in particular singing, is powerfully attractive to me. I am a former lyrical singer, and I need this in my life. If someone asks me why I don’t sing professionally anymore, I respond by telling them that I sing while working. I always have a melody in mind that accompanies me throughout my day.

What makes me really sad is the worsening political situation in the Middle East. I am very attached to the multicultural values of Lebanon. Right now, they are once again under threat, in a big way.

Since I mentioned singing, to wrap up I would say that the message from Schiller, put to music by Beethoven, the famous “Ode to Joy,” is more relevant than ever.

[1] Jean-Antoine Houdon, well known for his realistic work, was a French sculptor. Houdon had a talent for working with marble, but also with clay, plaster, bronze, and terracotta. Born in March 1741, he trained at Académie Royale de Peinture et de Scultpure, and died on July 1, 1828, in Paris, France.