Gillion Carrara walks an exciting career path that zigzags between fashion and metalsmithing: She teaches the one, practices the other, and in her pieces she seems to actively resist fashion’s “commitment to risk, subversion and irregular forward movement,”[1] preferring instead to work in a reduced palette of bold, minimal shapes. AJF caught up with her a couple of weeks before the opening of her next show, at Pistachios.

Note from the editor: The artist is not in the habit of dating her work, or giving it titles, and we have followed her preferred captioning system.

Benjamin Lignel: Gillion, you are a metalsmith, a fashion scholar, a librarian, a curator, and an educator … with an interest in photography and performance. You have trained in Italy (textile and fashion) and the United States, and traveled extensively as an instructor for the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), and more recently, as a lecturer, in Europe, China, and Japan. All of this marks you as a cross-disciplinary renaissance woman, and we already both know that this interview will only scratch the surface of your prolific endeavors. To give them a passing chance, and maybe get a sense of how it all happened, may I start by asking how you got involved both in making things and studying them?

Gillion Carrara: I became a metalsmith throughout and after years of intensive and productive workshops with master metalsmith Ted Drendel. For more than 30 years, I have been an active member of the Costume Society of America; for 10 years, a member of the board of the Costume Colloquium in Florence; and for the last year, a member of the International Council of Museums (in the area of fashion and textiles).

I continually study, research, write, discuss, disseminate. As founding director of the SAIC Fashion Resource Center, I organize and exhibit with great enthusiasm.

Studying, making, preparing my lectures, and attending art exhibitions serve as my self-actualization. It’s like breathing. I just can’t stop.

My career has been gratifying, as an SAIC adjunct professor. And last year I was delighted to honored with the Art Institute of Chicago Chairman’s Award. What a surprise!

I would like to begin with my life as a child. As long as I can remember, I wanted to learn and to make. I had very lofty thoughts and I liked to dress artistically, and to read novels, travel guides, and cookbooks, and experiment and investigate materials.

Since I was convinced that ancient Rome was “bella,” I studied the Latin language and planned to study art in that city one day. In fact, my life’s odyssey brought me to study in Florence, and then to work in Milan. It is a city I return to each year, as I love its streets and sense of design … and all “amici miei.”

For three months a year, I was able to work at a lathe in a small workroom nestled in the Tuscan hills near Siena, learning turning. From who? A briar-root-smoking pipe maker. So I learned from a woodsman how to find the best root and how to age the wood. From the butcher I learned how to age and clean buffalo and calf horn in order to incorporate the materials with silver. From the hunter I learned about animal hooves and honing knife blades. At the Museo del Legno in Orgia, I learned about local trees and the making of charcoal.

At the same time, I traveled with my husband to see art exhibits and architecture. He always called Italy a museum without walls.

To this day, in my Chicago studio, I display all materials on two long worktables. Then, I consider various gauges of silver as I fabricate blush brushes, shaving brushes, shaving blades, rings, bracelets, necklaces, gentlemen’s accessories, and vases with wood, bone, horn, briar root, and ebony.

You are a fashion scholar and a maker: How are these two different pursuits working together? How do you manage them day to day, and how do people react to this contrasted skill set?

Gillion Carrara: May I contradict you? I teach history of contemporary dress since the establishment of the industry of couture. I would not consider myself a scholar. Some of my friends pursue scholarly research and writing—that’s another planet. As you said earlier, I am an educator and a maker. Period.

Whether preparing a lecture or sitting at my bench, I start neatly, cleanly, and with the best of intentions. I am in the studio three days a week, in the Fashion Resource Center or teaching three days a week, and preparing for one project or another three days a week. I am so very fortunate—my workweek is nine days long! My life is my work. My work is my life. And yet I do find time to reflect.

I cannot say that there is a judgment on my contrasted skill sets. At times, I am satisfied with a lecture, my directions in the Fashion Resource Center, a piece of jewelry. I proceed. It is the evolution in the making that is my great satisfaction, not the finished work, particularly. I live in a world of artists. We multitask.

You hop between Tuscany (where you do your bone and horn shopping at local butchers’ shops) and Chicago (where you make your jewelry). What do(es) your workshop(s) look like? Where else do you source your materials?

Gillion Carrara: I wouldn’t say I “hop.” These were my homes. I tend to work most comfortably in my Chicago studio. My ground-floor studio is rectangular, with white walls. The large woodwork surfaces are rectangular with several workstations. The floor is cement. Three large metal shelves hold materials. Each day I clean the bench, the waters, the brushes, the blades, and the machinery, so that upon my return, all is in order. I begin my day.

Do you ever collaborate with other craftspeople, either to supplement your own skills or to batch-produce? What do you make of the studio jeweler’s tendential resistance to outsourcing?

Gillion Carrara: I do collaborate with a wood turner. He is a wood supplier, an expert turner, and has endless patience for my questions and requests. I also work in a glass factory with the glass artist. Yet in my studio, I work unaccompanied. It is my great pleasure.

Your lecture titles indicate a particular interest in pre- and post-war fashion designers and photographers, whose work was heavily involved in statement jewelry: Chanel, Schiaparelli, Man Ray. Why are they important to you?

Gillion Carrara: I find them innovative, original in design and fascinating in life. I attempt to collect and read all materials on each of them, as well as others of the period. My home office now is lined with shelves and columns of books. I am a symposium “groupie” and travel to see exhibits as often as possible. I traveled in a blizzard to see an Elsa Schiaparelli exhibition. I flew to Florence years ago for the weekend to see the first Biennale di Moda. Recently I flew to Atlanta to see the Iris Van Herpen exhibition. I have traveled to Antwerp and Amsterdam for short periods to savor exhibits of fashion. The images and impressions I take in reemerge in my classroom, in lectures, and at the Fashion Resource Center.

A series of large lathed wooden cuffs—which would not have looked out of place in Man Ray’s portraits of Nancy Cunard—is a highlight of your exhibition. What sort of person did you have in mind when you created them?

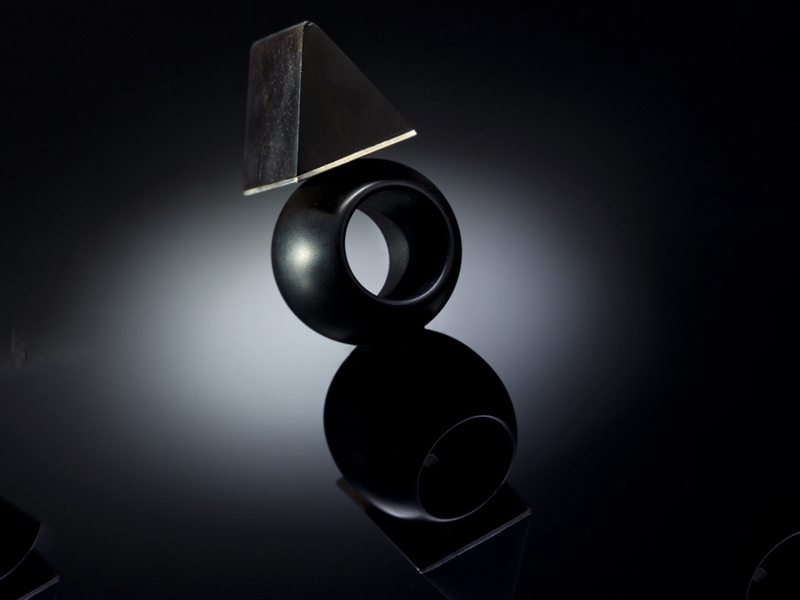

Gillion Carrara: On this you are correct! I was familiar with Man Ray’s portrait when I began the series. An objective is to feature the imperfections in the wood. And what kind of person was I thinking of? One who admires these characteristics. I often describe my work as sculptural, particularly the rings.

Reviews of your work describes it as “timeless” and put emphasis on the choice of rare materials, rather than “newness” or conceptual statement. Indeed, you turn encounters with exotic essences into bold, minimalist pieces. Are they meant as a remedy against the transience of fashion?

Gillion Carrara: I believe so. Creating a commonplace object does not capture my imagination. Creating an object of beauty unto itself holds great meaning to me.

You also design and make “male” accessories—shaving brushes, banknote clips, knives—and kitchen utensils. Do you distribute these through the same channels as your jewelry? Is there a particular appeal in producing such gender-specific objects?

Gillion Carrara: Creating these virtually obsolete accessories for a gentleman is very appealing to me, as I know there are people out there who appreciate the subtle elegance of fine personal objects with style and function. I exhibit my work in gallery-like stores where “design” is featured.

I am curious about what you think of the jewelry pieces featured on AJF: At one end of the spectrum, we have “author jewelry,” largely premised on one-off, experimental expressions of an artistic subjectivity via jewelry. The overlap with fashion or design, at that particular end, is limited at best, and wearability is optional. How do you feel about this aspect of contemporary practice, and do you know of precedents, in fashion history, when jewelry- or fashion-makers have decided that bodies would be accessory to their creations?

Gillion Carrara: There are few jewelers or silversmiths I admire, simply because I find sculptors more appealing for their success in original design and the craftsmanship, which I admire. I admit that most jewelry I see these days is too overworked.

The body can indeed be an accessory, but in another sense. The body in motion serves to convey the innovation of the garment. I have read that more than one fashion designer studied the clothed body in movement to better access the garment.

I’d like to end with a question about transmission, and new beginnings: What advice would you give your younger self if you were to start your career as a fashion scholar and metalsmith today?

Gillion Carrara: Easy. Consider the best of art schools or universities with a metals department. Study, experiment, vary materials, apprentice. Read. Know arts and architecture. Stay curious.

I rather like the one-time practice in Japan of apprenticing in the area of textiles, for a contracted 10 years. And surround yourself with the most nurturing of educators, friends, and lovers.

Work in the exhibition ranges from $80 to $1,200.

INDEX IMAGE: Gillion Carrara, gentleman’s shaving brush, silver gray badger hair set in bone, horn and silver handle, 89 mm wide, photo: Tommaso Buffano

[1] Anne Hollander, Sex and Suits: The Evolution of Modern Dress (New York: Kodansha International, 1995), 15.