James Tergau: After 23 years, chp…? has come to an end. Can you tell me more about what happened? Why was the label discontinued?

Gijs Bakker: There were a lot of factors that played a role. Sales lagged behind the investments, not only in terms of money, but especially in energy. That’s one of the most concrete reasons. Another reason is that stores, design stores in particular, have more or less disappeared. Influential stores like Colette in Paris are gone. 10 Corso Como in Milan is not what it used to be. Those truly high-end design stores have mostly ceased to exist. Murray Moss is another example.

And museum shops are the worst. Worldwide, they sell the lowest quality. Even museums that specialize in jewelry sell the most ordinary jewelry in their stores. I understand that museums need these types of stores to cover their financial deficits, rent them out to commercial groups that are not directly linked to the museum. MAD, in New York, is a good example. At times they make very interesting exhibitions, but when you enter their ground floor you’re overwhelmed by a huge bazaar with low-quality products. I understand very well how this works, how it’s a revenue model for museums to survive and how museum management has no say in which products are sold. But still. These are issues that we came up against.

Related: 25 Years of Ted Noten

Related: AJF Interviews Katja Prins

Related: Liesbeth den Besten’s 2014 Essay on the Golden Schmuck Standard

Working with designers, like during our latest project, Device People, remains fascinating to do, and presenting such themed collections during the Salone del Mobile in Milan is a challenge that I really enjoy, but then during the follow-up we ran into issues like the ones that I just mentioned. Then what arises is a bit of a chicken and egg story, and to get out of this dead end you have to invest in the development of new sales channels. Unfortunately, chp…? doesn’t have the means to do so, and then you have to reflect on whether you still want to continue. My interest is purely in the design content of the projects I have done all those years and not the hassle about distribution and so on. It’s something I find extremely interesting, but it has to be pulled by others. And finally, to crown it all, we heard that the producer of the Triadic bracelet, by Charles Marks, was no longer able to continue production of the piece as he was heading toward his 90th birthday. It all makes sense, but the Triadic was our best-selling product in terms of turnover, and for different reasons we weren’t able to continue production of the bracelet ourselves.

So do I understand correctly that it wasn’t really a difficult decision to make in the end?

Gijs Bakker: Indeed. In fact, it was all just a direct consequence of everything that had happened, and our choice to discontinue felt really self-evident. What I really appreciated, though, was that when we made this decision, we first approached all the designers to tell them about chp…?’s end, and this generated a lot of heart-warming reactions. People were sad to hear the news, but also really understanding.

What are you most proud of in terms of what you’ve achieved with chp…?

Gijs Bakker: My goal once, when I started chp…?, was to bring together the world of design with the world of crafts. Those are two strictly separated areas. Now, looking back, I notice that, especially from the design world perspective, there’s more respect toward some of the people in the crafts world. The other way around, however, not so much. Craft can be very English, very American in this context, very much oriented toward the artisanal.

Do you feel that people from the crafts world don’t understand the conceptual approach to design and look down on a lack of craftsmanship?

Gijs Bakker: Exactly. My ambition to confront those two worlds and to bring them together has always originated from this idea of taking a concept as the starting point, using a conceptual approach to design. You can make something from a design mentality or from a crafts mentality. What I think I’m most proud of is that a number of designs for chp…? have originated from the design briefs that we wrote, like Body Stories, Rituals, Device People, and they have resulted in products that would otherwise never have come into existence.

You’re saying these designers had no intrinsic incentive to work this way?

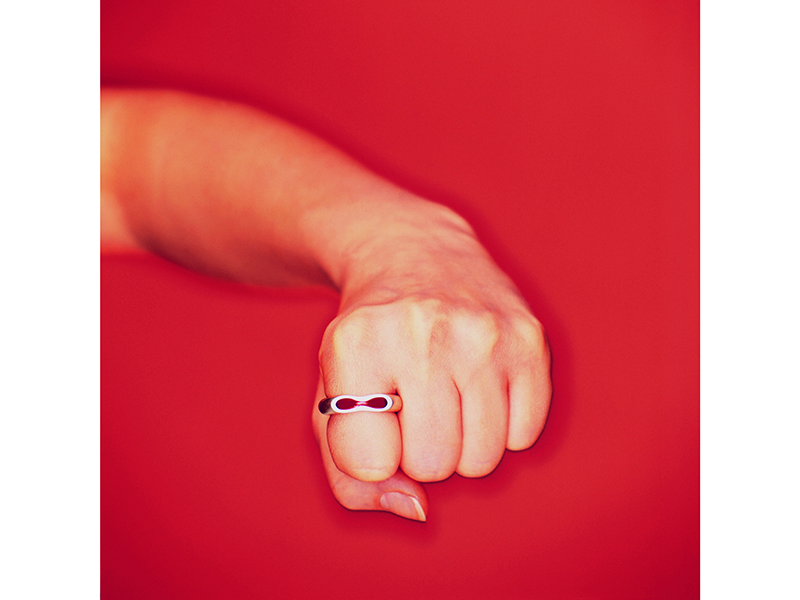

Gijs Bakker: Right. For instance, the Index, by HOKO, is a very nice example of this. The concept originated within the Global Identity collection. It’s based on the historical tradition in which high-ranked Asian women would wear “jewelry” specifically designed to protect their long nails—a piece of cultural history and of historical craftsmanship is combined here with a contemporary practice. The Index doesn’t protect coveted nails, but the skin that’s used to swipe a mobile device. Of course, this is an example of a design made by young designers influenced by craft.

Another product is the Bound by Blood necklace by Katja Prins, which originated from the Rituals collection. It’s a large blood red collar that combines all sorts of prayer beads, chains from Catholic, Muslim, and Buddhist traditions, turning them into a meaningful piece of jewelry. A very conceptual work by a designer who was not accustomed to this conceptual approach.

These are all very specific examples. It’s of course indicative that we’re talking about a world of design and a world of contemporary jewelry, but do you have the feeling that something has changed more generally in this respect compared to 23 years ago? Do you feel that this gap between these two worlds has become smaller, or only larger?

Gijs Bakker: I’m pretty negative about this. In the world of contemporary jewelry, with a few exceptions, I think that there’s hardly any development taking place. Actually, with the rise of this notion of “art jewelry,” I feel that jewelry has even distanced itself further from design.

Jewelry has moved toward the art world, instead of toward the world of design?

Gijs Bakker: And then the art world distanced itself from jewelry immediately. In my opinion, this pretense of jewelry being art, 99% of the time this is not fulfilled, except perhaps in regard to the price tags.

In which sense not fulfilled, in being conceptual like art can be?

Gijs Bakker: Yes, with a lack of any interesting concept.

In the 1960s already, you were looking for a new perspective on jewelry, referring to your designs as Wearable Objects, as opposed to something like Wearable Artworks or Wearable Decorations. Does this new notion of jewelry being an artistic expression counter your idea of what a good piece of jewelry should be?

Gijs Bakker: I think that jewelry has detached itself from the body. One of the rights to existence for jewelry is that it relates to the body, that it can respond to it, connect to it, and confront it. Not only physically to the body, but also to the human aspect, to the person wearing it. On a small scale, chp…? has brought the worlds of design and contemporary jewelry together. In that sense, we’ve achieved a bit of what we aspired to. But in the broader sense, jewelry has moved in a very different direction, more toward art than design.

Twenty-three years ago, you won the Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds Award for Applied Arts and Architecture, an accolade that came with a large sum of money that allowed you to set up Chi ha paura…?. If you were to win another one of those awards, what would you do with the money now?

Gijs Bakker: I would invest in MASieraad, and set up an institute where talented people from all over the world are invited to study, to work together—a kind of knowledge institute. MASieraad is our new foundation that aims at the promotion of jewelry in a broad sense, through development of education, lectures, exhibitions. I’m part of its board, together with Liesbeth den Besten, Ted Noten, Ruudt Peters, Leo Versteijlen, and Liesbeth in’t Hout. Our first project was the temporary experimental two-year masters program called Challenging jewellery, which started in September 2018 at the Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam. For this masters program we scouted BLESS, formed by Ines Kaag and Desiree Heiss, as head of the department. They’re responsible for the educative program, for all the classes, but we, as the board, are there to advise and to keep control over the quality of the education. Challenging Jewellery is now going into its final phase, with students graduating end of June.

We’re currently orientating ourselves to place a temporary masters at another institute. As MASieraad, we have prepared 10 statements, a sort of manifesto available on our website. It starts with us cherishing the word sieraad (jewel) as a badge of honor, because of the relevance of jewelry for contemporary design in a broad sense. And then it continues. In 10 statements we’ve set out where we stand and how we think about it. It’s also the basis of our educational program. MASieraad keeps me busy a lot. It’s a vehicle that I can put a lot into.