- The Kātahi me Ināianei/Now and Then: Alan Preston exhibition, at Objectspace March 16–May 19, 2024, presents a selection of jewelry from Alan Preston’s personal collection

- Preston is a founding member of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Fingers Co-operative. Fingers Gallery celebrates 50 years in existence this year

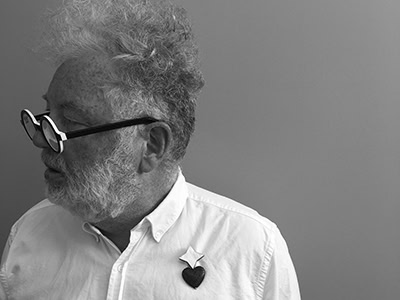

- Preston actively wears jewelry, and once sported 27 pieces of jewelry to a special contemporary jewelry event

Philip Clarke: You have a show called Kātahi me Ināianei/Now and Then, at Objectspace. Tell us about it and how it came about.

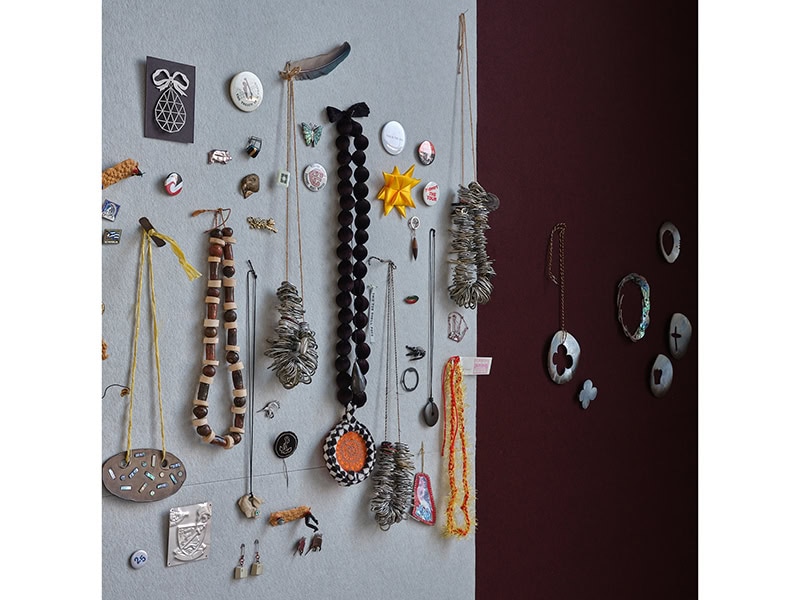

Alan Preston: Sam Hartnett came over to my place to take photos, commissioned by Objectspace for historical purposes. I don’t know why, but they realized one image with everything in it was my bedroom wall, so on short notice they asked if they could exhibit the wall, or all the things on it, which is the jewelry, brooches, and other things that I wear.

At the opening of Kātahi me Ināianei/Now and Then, you talked about its title. One of the things I’ve always admired about you is your commitment to using te reo Māori and tikanga [behavioral guidelines for living and interacting with others] long before I ever heard many other artists use it.

AP: They wanted me to give it a name. “Now and then” seemed good as things go up and down on that wall now and then. It needed a Māori name. In Māori, the past is always in front of us, coming before the future, so the Māori title reads as Then and Now, followed by the English Now and Then. Of course, the Māori needed to come first, because our new government has decreed that government agencies have to abandon their Māori names!

Many years ago, about 1961 or 62, I went to Māori language evening classes to learn te reo, and since then I’ve been to many others and been taught by many teachers. I don’t know what it was, but I just felt that you needed to speak the Māori language because it is the language of the country.

Georgie Kirby [Dame Georgina Kirby] was one of my teachers and she used the Atarangi method of teaching, which meant that students had to teach new students so it was hard to progress because you were always going back to basics. So I never became particularly fluent. After going to Papua New Guinea, where there are 700 languages, it just seemed important to keep going, so I went to classes up until about 2000. When I was an adjunct professor at UNITEC I’d get calls to speak at Te Noho Kotahitanga, the UNITEC meeting house, designed by Lyonel Grant, because you couldn’t speak in English at formal events there and I was one of the few Pakeha [New Zealander of European heritage] staff who could speak Māori. I can think in Māori, which is good. If I try to think in French, Māori will take over!

It was Georgie who said that I must come to the hui at Te Kaha when Nga Puna Waihanga (the national body of Māori Artists and Writers) was formed in 1973, so I did. There were a few Pakeha there and we were called Ngati Whriki. There was a lot more fluidity at that time about such things. When Georgie came back from the launch of Te Māori in New York [1984] she returned the jewelry, made by me and Roy Mason, that she’d borrowed, and told us that whenever she’d been asked “who made it?” she’d said “a cousin.” The stuff I made in the 1980s was much more derivative.

You once publicly challenged a description of yourself as grandfather of contemporary NZ jewelry and identified yourself as a great-uncle. Why did you use that term, and how’s the family?

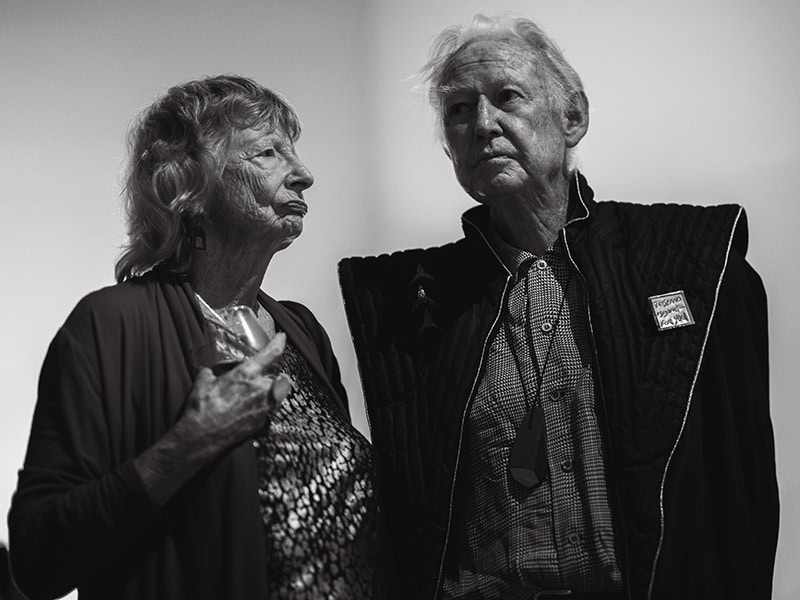

AP: That was at JEMposium in 2012! Someone called me “grandfather,” but Kobi Bosshard is a year older than me, so in terms of seniority he’s the grandfather. I called myself great-uncle just because that seemed like a good way to convey a similar age. I know some people have called me the “godfather of contemporary jewelry” and maybe that’s because I was the oldest person involved with starting Fingers.

The family, well, it’s active and strong. Of course, it includes a lot of young people who are quite independent of the old ones, and it’s nice that we’re not included in some things anymore, that’s healthy. Finger has people applying all the time to show with us, but we can’t accommodate many new people. There seem like a lot more part-timers who don’t make much work. It’s difficult to make a living and more difficult if your work is challenging. And it is still the more accessible work, rather than the challenging work, that keeps a place like Fingers going.

What about education?

AP: Well, a lot of people qualified from jewelry courses, but where did they go because they didn’t always practice? If I think about the start of Fingers, more of them had other academic training rather than art school training. So I think there have always been different pathways into practice. Not long ago, Fingers suggested a young jewelry grad go and work with Kobi [Bosshard], and she came back saying that she’d learned more in three days about metal skills than she had in three years studying.

Internationally, I think contemporary jewelry has reached a turning point, but I don’t know where it is going!

There’re more makers, which means that jewelry has a constant visibility even if the number of outlets is slightly reduced, with places like Quoil no longer operating.

I can’t think of a maker who is a more conspicuous and well-turned-out advocate for jewelry. I can recall you wearing 27 pieces of jewelry to a special contemporary jewelry event! Talk about your life as an advocate.

AP: I do like to wear jewelry, but quite a lot of contemporary jewelry people never wear much. I used to just wear my own work because that was all I could afford. Then I could afford to buy other people’s work and I’d get things from pin swaps. And I look at auction house catalogs, partly to alert other makers if I see their work is coming up. And sometimes I buy work, and stones, at auctions. I like old paua jewelry. What am I wearing? A Peter Deckers brooch and a MAD brooch I got given in Munich.

There are two parts to Kātahi me Ināianei/Now and Then: your collection of other people’s work bookended by two small groupings of your own work. Tell us about why these works of yours were chosen.

AP: My initial understanding was that the exhibition was going to include some of my work. I just got a whole lot of works of mine together so we could choose some. When I’d done that, it was clear that there was too much and to show them all would need a separate show. We’d agreed that there would be a red border around the installation of my collection. Jacob [Preston’s stepson] installed the works exactly as at home. When we came back the next day, the Objectspace staff had turned the installation from a re-creation into a proper gallery installation, and they choose my shell works to sit in the red border.

A selection of Sam Hartnett’s photos was a photo essay in the Autumn 2024 issue [the seasons are reversed in the Southern hemisphere] of Auckland’s Metro magazine. One thing that struck me about the interior of your house and studio was how layered, shall we say, it was, in contrast to the clean-cut or graphic character of your jewelry. It is surprising to think of that work emerging from that environment.

AP: Well, it isn’t always that “layered”! I do occasional tidy-ups, but after a while who would know? When I moved into the workshop, I moved some stuff into it that I’ve never gotten around to unpacking, and then I’ve had stuff from my family that is still packed up. Marina Elenskaya from Current Obsession just visited, and she said she wanted to do a residency in my studio to catalogue everything! It is a bit out of control. But I front up to lots of jewelry events, representing Fingers, representing other senior makers, so I’m busy outside of the studio for contemporary jewelry—it’s a trade-off.

I’ve always considered you a very politically aware maker whose work can be subtle and in-your-face political. How large an interest is politics for you?

AP: It’s not overpowering, but I’m certainly interested in the dire state we’re in with the current government [conservative tending to populist]. It’s a constant. We have dreadful world politics.

In 2008 Damian Skinner wrote a big book about you and your practice, Between Tides. If you were updating it, what would you say or want to include?

AP: I don’t think there’s anything I didn’t say that I’d say now. I guess the works that aren’t in there that I like are Ulubanana, a necklace made of Abyssinian banana seeds. It’s the banana with the big leaves that grows everywhere. And there were no Karaka berry necklaces in the book. There’s a new necklace in the show, which I made for it, of spiral shells [spirula spirula], which you know are very fragile. The more you wear that necklace, the more the shells will break, which I don’t mind.

Fifty years is a very long time to sustain both a practice and to be part of the management of Fingers Co-operative, which has managed New Zealand’s longest-operating contemporary jewelry gallery since 1974. Tell us about Fingers. What are the secrets of long term success?

AP: It’s really difficult to know! Possibly because it was initially run by makers, and only as we evolved did we employ people to work with us. Only two of the members work in the gallery now, but all the others who work there are from the contemporary jewelry community. Other galleries aren’t run by people from the making community. We’re all from the making community, and aware of changes and developments.

Fingers “runs” on selling accessible jewelry, even though we’re known for challenging work, and we’re very successful at selling that sort of work for people like Karl Fritsch. Maybe the fact that we can appeal to a broad range of shoppers is one of its secrets. And maybe it is continuity, as we’ve still got founding and very early members like Ruth [Baird], Michael [Couper], and Roy [Mason] still involved. And we’ve changed—technology makes some things easier. Warwick [Freeman] left because he said he couldn’t stand the meetings. When he left we stopped having meetings.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org