Corpus • Parallel Investigation• Reflection Activity • Still

Objects • Abject Hidden • Reveal Shiny • Dull

Volume • Space Missing • Present Skin • Surface

Beyond • Between Internal • Empty

Marthe Le Van: Two radical silversmiths, esteemed makers, designers, and teachers, unite for a two-person show. Do you feel you have been on parallel paths? Why intersect now?

Anders Ljungberg: We have been working in parallel at different times, both as artists (in a number of exhibitions) and in teaching (Stockholm and Oslo). For me, there are relatively few people in the field of silversmithing I wish to collaborate and exhibit with, and David is definitely number one among these, because I find a kind of friction grinding in his work that is both disturbing and very sweet, but also because he simply is one of the most interesting people on the contemporary silversmithing scene. There is a need to raise this artistic discipline out of a context filled with limitations and bring it into a contemporary relevance. This, I believe, both David and I have the same pronounced ambition to do.

David Clarke: Firstly, Rosemarie Jäger invited us to exhibit together. She wanted this to happen and saw that there could be an interesting conversation between the works and us as artists. However, we have known each other for eight years and regularly meet in Stockholm where we discuss, share our thinking, and sometimes argue—we’re a bit of an odd couple. Our friendship means that we have built up a sense of trust and honesty in our discussions, which is a rare thing in the small and sometimes petty world of silversmithing. For me, this exhibition isn’t really about working in parallel, it’s much more focused on how ideas can collide and works play off one another.

What explorations, in thought and action, led you to make the pieces in What Is Not?

Anders Ljungberg: I have, in my work, highly devoted myself to examining spaces that exist beyond a physical reality. This can be about the interior of a vessel that is not completely reachable for us, about what actually happens in a pipe system beyond the tap, or what we imagine is going on behind the wall defining and confirming our physical reality. Some of my works slide into or out of the wall, in a state between physical reality and beyond a spatial dream. Most of the works in What Is Not have, however, started from a bureau that I’ve simply been cutting up. The idea behind this was to reveal the previously hidden, and, out of this form, an arised “nudity” provides space for items that fill and examine those naked, empty spaces.

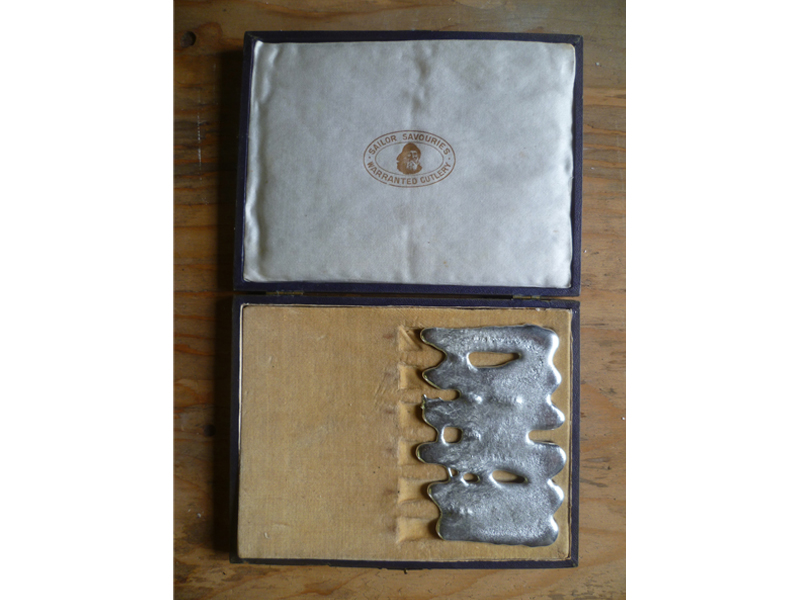

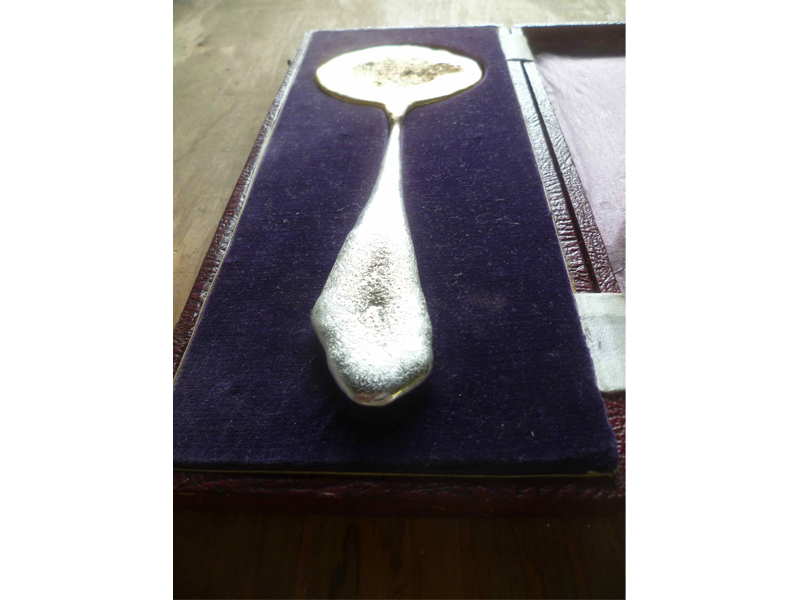

David Clarke: I felt it was essential for me to develop a new body of work. I wanted to actively explore new territories, which would allow me to develop my visual language, tap into deeper emotions, and utilize different tools. I had some key words in mind to anchor me: void, skin, and loss. These led me toward casting pewter and lead, which was a surprisingly quiet and intimate process as you handle the molds, swirling the metal until it sets … literally, waiting for movement to cease and a skin to form.

What was the most challenging piece to make in this show, and why?

Anders Ljungberg: It is very difficult to say because I often work with my objects in a dialogue with each other during the process. If you mean technically (or perhaps this is artistically—it is sometimes not possible to separate them), it has been difficult to create the illusion of gravity or the tension in surface that I was looking for in most of the works. In some of the works, the ambition has been to be relatively close to reality (such as the Bag Beneath #1, which is a three-dimensional “realistic” drawing of a plastic bag), while in other pieces, I have had a more illustrative and distanced approach.

David Clarke: For me, the act of making isn’t challenging, as I make all the time. However, the absolute challenge comes from deciding what to make and in determining the relevance of an object once you take it out of the workshop context and place it in front of an audience. There was a degree of active experimentation involved with the method I used. When I felt something was less successful than I wanted, I was free to melt it down and start again. That’s incredibly liberating.

Several pieces in What Is Not live in context with another object—a table, a box, part of a chair. What is the reasoning behind this?

Anders Ljungberg: The fact that the law of gravity causes all material to constantly strive toward the center of the earth has been something I have worked with in many earlier projects. On this journey of gravity, the material and the objects being formed out of them meet other material. In this encounter, objects create conditions for each other’s existence. The jug needs the table to not keep falling; the floor needs a house construction to be a functional floor; the house needs the ground, and so on. Nearly all of my work has been about the relationship between the objects themselves, the object and the user of it, and object and space. In my mind, an object is not existing without those relations. It becomes in this friction with the other.

There is a sharp tension in your objects. Simultaneously, your pieces seem to desire activity but are made incapable of it. Why is suggesting function but denying it important to you?

Anders Ljungberg: Actually, most of my works in this exhibition are perfectly possible to activate, which is something I want to encourage. In this exhibition, for example, I let people drink warm apple juice from one of the vessels, which offered a completely different understanding of the piece than just looking at it. The tactile, bodily experience through handling is important to me. It is simply a further dimension to the understanding of the object. Sometimes, however, I choose to remove the practical function to highlight a different concept of function. This has been a long tradition in silversmithing. For example, some Baroque pieces had connotations to practical functional items, but nevertheless the function was essentially social. My work is often around the more emotional aspects of everyday use that create inner structures in our lives. For me, it is sometimes more efficient to show those emotional aspects by removing the practical dimension and, instead, allow the use of them to take part as a dream or a thought of functionality. This creates a poetic dimension that might not be there if they were only practical.

David Clarke: It’s important to state that the original object and material has been removed and its primary function has been corrupted. In consciously removing the original, I’ve created space for new thinking and interpretation, which is intentionally not of the practical but is of the emotional. These pieces have a direct relationship to the domestic environment, as all of the originals were highly functional, well-used objects from my mother’s house. In developing a “second skin” through casting, I have created a neutral surface on which audiences can project their own narratives.

Do you intend your pieces to have personalities or express emotions?

Anders Ljungberg: Absolutely yes. I think that applies to both of us. I often find myself talking about my works as if they have their own vision/idea, which is reflected in titles like Jug Looking for a New View, etc. My work highlights the absolute highlights (as mentioned above) of emotional perspective in the user situation when pouring, drinking, etc. My idea about objects is that, when they become a part of our bodies and minds through use, they define us as human beings and we complete them as objects with all the dreams we have put into them since ancient times.

David Clarke: Historically, I am known for producing playful, offbeat work with plenty of eccentric characters in the ranks. I enjoy the naming process almost as much as the making, and I always try and come up with something that reflects an object’s personality. However, this body of work is coming from a very different place and should evoke a different kind of emotional reaction. I based these pieces on objects that all meant something to my mother, and the collection is a direct response to her death last year. I feel it’s the most poignant body of work I’ve ever made.

Who has inspired you in the past, and how? Who is currently making work that interests you, and why?

Anders Ljungberg: What inspires me is the same as always—trying to see what is hidden in everyday life behind layers of habituation. When it comes to art and makers, there are loads of them, but lately, two artists I have found interesting are Markus Schinwald and Adrián Villar Rojas. But also, the Baroque period is inspiring me because of its different concepts of functionality behind the wall of functionalism.

David Clarke: I’m finding a lot of parallels between architecture and my work at the moment, even though the scale and purpose is different. I was working in Japan last year and visited Ryue Nishizawa’s building on the island of Teshima. This was a deeply humbling and engaging experience that has stayed with me. I’ve been exploring a sense of space being contained and defined within a skin, and also wanting to re-create something that would connect and captivate the viewer in the same way that that building did to me.

Have you recently experienced anything that filled your mind with wonder or your heart with joy? What was it?

Anders Ljungberg: Definitely setting up this exhibition together with David. But also, after being so focused on my own work, meeting my students in their doubts and dreams in making art.

David Clarke: I am always highly motivated by a decent slice of cake and getting back to my own bed after weeks on the road working—that usually fills my heart and stomach with joy.

Thank you.