Olivia Shih: Congrats on being named one of the finalists for the Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant! As one of the most thought-provoking jewelry artists of our times, it’s no surprise that you were recognized as a finalist. For those who might not be familiar with your work, can you introduce yourself to our readers?

Christoph Zellweger: Well, I was born into a family of gold- and silversmiths. My mother is a hard-core jewelry enthusiast, ran a shop as the fifth generation, and my father still does his own stuff as a silversmith. They’re both in their 80s now. When I started my training, I already had an idea about the limitations and the potential of jewelry as an expressive artistic medium. I worked for long in the field producing fine jewelry for the luxury trade, before I had had enough. It wasn’t what I wanted.

What drew you to contemporary jewelry?

Christoph Zellweger: I felt that I needed to move on, the field was too static, the jewelry predictable and, other than the technical challenges, boring. I wasn’t working for people that were interesting to me, so I chose to return to school when I was 30 and turned toward a more experimental, critical, and interdisciplinary practice. My primary audience now is genuinely interested in contemporary design and art, open, and often engaged in the social and the political—and my audience is expanding too, as I’ve crossed borders into other fields, which has been very enriching.

The works I admire, be they contemporary jewelry, product design, or art, do not want to please. They’re out to challenge themselves and others and convey an original point of view. They’re statements made by rigorous and independent minds, be they the minds of designers or artists.

What does contemporary jewelry offer you as a medium?

Christoph Zellweger: My work often starts with an irritation, a critical thought, something social or ethical. When you say my work is thought provoking, it’s because reality provokes me to respond.

I see contemporary jewelry as a great medium for triggering discourses. When worn, jewelry becomes a perfect talking point, a silent but original opening line that is neither predictable nor banal. A contemporary piece of jewelry, when worn, sets a tone and sometimes conversation topics, too. Of course, wearing contemporary jewelry requires competence and confidence, a wearer with the ability to deal with the consequences of a visual invitation.

When wearing or collecting contemporary jewelry, one can’t stay indifferent. The object and the wearer, they’re both about something. There’s an interplay, the object becomes performative, interlinked with the attitude of the wearer, and that’s what intrigues me.

The book you proposed for the Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant, Rituals of Self-Design, centers around the idea that the human body is increasingly designed and manipulated through plastic surgery and self-optimization mindsets, such as the quantified self. What exactly is the quantified self?

Christoph Zellweger: Well, self-tracking is another label for it. These are social movements, meaning data are collected using wearable sensors—like the ones worn on the wrist, for example. It’s all about measuring, analyzing, quantifying, and of course optimizing one’s body and mind.

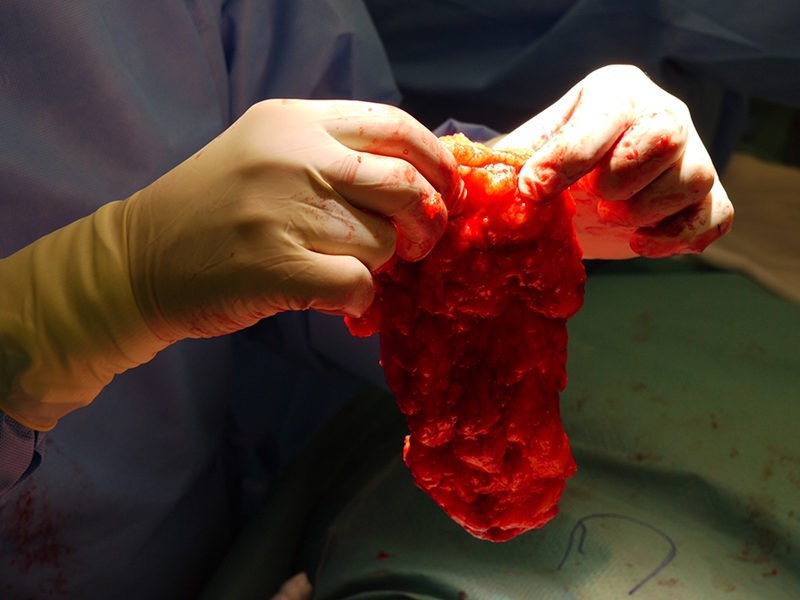

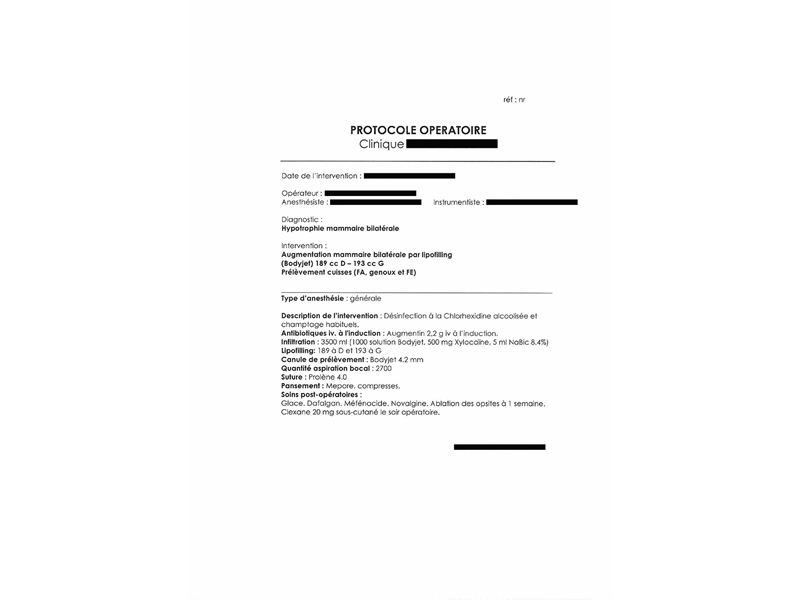

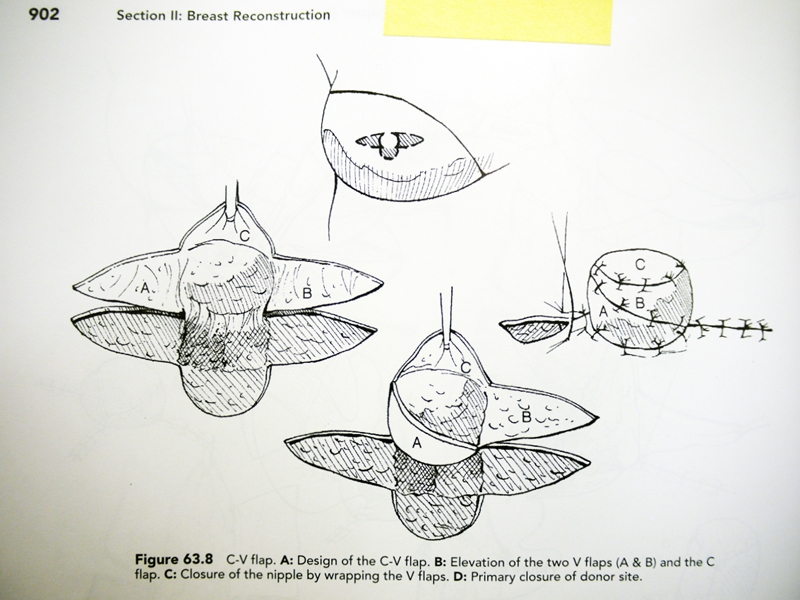

With Rituals of Self-Design, which I’m currently working on, I want the reader to step into a journey through operation theaters, DIY workouts, luxury interiors, and social obsessions—the places where I think jewelry meets Botox, Fat, Big Data, and irritatingly naive ideas about beauty and eternal youth.

What role do jewelry and adornment play in the world of plastic surgery and other forms of self-optimization?

Christoph Zellweger: Operated people recognize each other, mingle or avoid each other, create subtle or obvious communities by identifying the surgeon’s signature. So it’s about recognizing both, jewelry and plastic surgery, as aesthetic practices connected to a long tradition humankind has with body modification. Tattoos, scarring, reshaping skulls and feet are interventions probably as old as creating sophisticated objects attached to garments, which is the currently dominant “Western” form of body adornment. So my statement is that there are probably reasons why jewelry goes corporeal; people increase their investments into the look, the expression, and the functioning of their bodies, rather than into attaching precious objects onto their garments. For me this is an observation, a trend connected to the phenomenon of self-design, which is defined as the pressure individuals face today to engage in rituals of self-optimization.

In your recent work on self-design, you do in-depth research with plastic surgeons, personally collecting information and data. How are these cross-disciplinary collaborations important to your work?

Christoph Zellweger: Over a very long period of time, I’ve been following the latest medical advancements and found it fascinating to see what it’s possible to do with a scalpel. I also had an uncle who worked in an accident hospital and nurtured my curiosity about his craft. He talked to me about long shifts reassembling bones and total makeovers after serious accidents.

But when it came to plastic aesthetic surgery, which is most times a self-inflicted procedure, I started questioning intention, outcome, and appropriateness of means. I still believe that not all that’s technically possible needs to be done. I found myself taking a more conservative position, which actually surprised and irritated me at the same time. I asked myself, on what grounds do surgeons make aesthetic decisions? And do patients really know what they’re buying into? These questions triggered my wish to deepen my understanding of what really happens in the operation theater—but not as a patient! (Laughs.) So I managed to witness many operations as an artist researcher, an observer. These gained insights were crucial; I needed first-hand information, and my experience informed my work. My position has always been critical and my intention genuine when talking to surgeons and patients alike; it’s a learning process, both ways.

Collaborations are indeed a two-way street. What do you think you specifically, and contemporary jewelers in general, can contribute to the world of medical science, social science, and product design?

Christoph Zellweger: When I was invited to an orthopedics conference in Belgium to talk about my artistic research, I made sure that the talk was entertaining, and I showed images of my work, “fictive implants in biocompatible steel.” The amused audience asked good questions, which taught me that I could make my point while appreciating the challenges posed by an audience outside of my field.

I recall another invitation for an artistic talk at a large conference of facial surgeons and orthodontists, where I was one among 30+ speakers in Bale, Switzerland. I tickled my audience of about 120 doctors by cheekily posing the rhetorical question, “On what grounds are facial surgeons making aesthetic decisions—without a degree in design or art?” Where do they draw the line between reconstruction and interpretation? The discussion continued through coffee breaks, and I recall two slightly overconfident representatives of the profession who claimed that their versatile craftsmanship and aesthetic sense for proportion can’t be questioned. So in this way I learned about the surgeon’s pride as a craftsman and the fact that surgeons are aware they’re making aesthetic and intuitive decisions. I also found out that the medical field often isn’t particularly scientific—at times it seems to be a hands-on profession, not dissimilar to my own! (Laughs.)

Back to your question: I believe that people with a background in jewelry and a good understanding of the role personal objects play in people’s lives can greatly contribute their knowledge to other fields. A good example is Jayne Wallace, who explores the potential of jewelry, digital technologies, and physical object-making in support of patients’ healing or recovery processes. Check out her site.

What kind of reaction do you hope your book will elicit from the field of contemporary jewelry?

Christoph Zellweger: Genuine interest, curiosity, and encouragement to leave the comfort zone. There’s a lot of knowledge in our field that, if applied in other fields, could be very valuable.

It’s often noted that the contemporary jewelry world can be insular and difficult for the average person to enter. Print publications are one way of communicating in an accessible way with a wider audience. In what other ways do you think contemporary jewelry can be discussed, promoted, and ultimately reach a more diverse audience?

Christoph Zellweger: Every specialized community is insular by definition, otherwise it wouldn’t be specialized. I’m interested in genuine interest and not in diversity alone. Can I reach and touch people with my work and issues? Am I using the right and authentic strategy? Are shops, galleries, or museums doing their job, or should I look for opportunities outside established systems, like pop-up galleries, pop-up stores, websites, or video? These questions count.

For me, it’s about content, not about “likes.” I don’t even want people to “like” my work, but I want them to engage, to find my work in a specific physical context where being indifferent is not an option. My work is physical, I want to physically pick up my audience, through an experience. In this way, I look for real confrontation, not for promotion.

Have you heard or read anything that shifted your perspective lately?

Christoph Zellweger: My perspective shifts constantly, forward, sideways, backward. Twenty years ago, I read that families in South America were taking out loans to afford breast implants for their young daughters, instead of investing in a handmade piece of jewelry for their 18th birthdays. This opened my perspective, but didn’t shift it. Times change, maybe now families support surgery, the health insurance covers the costs, and the girl buys herself a piece of jewelry on her 18th. (Laughs.)

Currently, I read too many articles about promises: smart phones, smart homes, the era of digitalization, industry 4.0, permanent access to the network, information, artificial intelligence. Of course, all this makes me think, especially about the role of jewelry in the future when wearable computing, handheld devices, and smart implants will compete with the surface on the body that is traditionally occupied by jewelry.

But I’m also relaxed and curious about counter-movements and the positions my students favor. They will deal with similar questions in the study program I’m directing in Lucerne. Obviously, there are new niches and markets out there, into which experts with a background in jewelry should dive.

Contemporary jewelry, to me, becomes more and more faceted, and I place trust in a vibrant debate about what jewelry can do for people in the future.

Thank you!