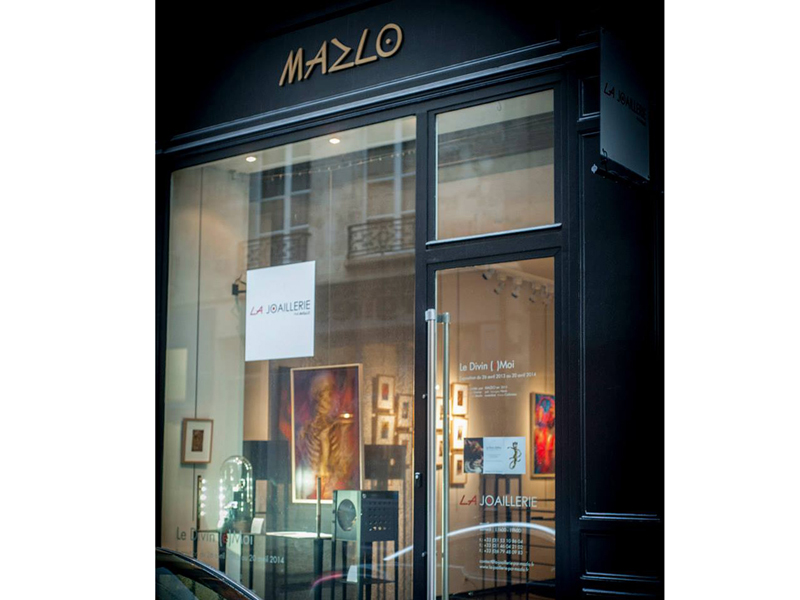

Located in the Paris district of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and with a history of attracting creative minds and artistic visionaries, Galerie La Joaillerie par Mazlo is an undeniably unique gallery with a singular focus: to create a venue for artist jewelry that transcends boundaries and disrupts the artistic hierarchies often foisted upon the medium. In this interview, I speak with Céline Robin, the exhibition curator at La Joaillerie, about her curatorial approaches and her unique perspectives on jewelry as an art form.

Adriane Dalton: Begin by giving our readers some background about the gallery and its founder, Robert Mazlo.

Céline Robin: Art jeweler Robert Mazlo founded the gallery in 2010, with the idea of converting what was at first a personal showroom into an exhibition space where he could finally achieve his dream: sharing a space with international artists. He wanted to promote and support diverse artistic approaches by inviting artists and art jewelers to participate in group shows and solo exhibitions. Thus the gallery soon became the office of the association we created together. Our common interest for art jewelry materialized through this place and its vocation.

How long have you been involved with the gallery? What’s your role?

Céline Robin: I’ve been involved since the very beginning as an active member of the association. Besides the administrative tasks, which are the regular basis of any association, my role is to organize events, to bring artists together around a theme to build exhibitions, which is more or less the function of a curator. It also includes writing, supervising the graphic design and production of catalogs, and other communication.

Describe your interest in art jewelry, both personally and professionally.

Céline Robin: After graduating with a degree in art history and classical literature and before taking part in the association, I worked in the art market for 10 years as a specialist in Egyptian archeology. My real interest in jewelry originated during the period in my professional life when I familiarized myself with antique jewelry. At that time, I realized how deeply jewelry is rooted in the ritual part of our lives. From the “gold reward” ceremonies of ancient Egypt to the sacrifice of the mother’s ornaments in India (to symbolize the separation between mother and son), whatever the culture, religion, skin color, gender, time, and space, we’re all connected by the same need to ornament our bodies and to express something through jewelry. It’s the only art form that has such a universal value. It’s a genuine language hidden behind seemingly frivolous considerations. Which makes it all the more subversive.

On a personal level, as I don’t come from the jewelry world, I am not, so to speak, a jewelry addict. Actually, I hardly wear jewelry, even though I collect it.

For me, jewelry is all about intimacy and, at the same time, about interacting, engaging in a dialogue with others, exposing one’s inner self to the outside. Sometimes I feel secure enough to engage with this, but most of the time I just prefer remaining neutral.

In French, we have this expression meaning that your professional activity shapes you, but sometimes in a “bad” way. It changes your attitude. I don’t know if you have something similar in English. I’m probably influenced by my profession in this way. When you know how to analyze someone’s personality through their jewelry, you don’t wear jewelry casually.

What is the selection process and criteria you use when considering artists to represent?

Céline Robin: First, I consider the skills at work in the conception of the jewelry, the level of technical execution and of craftsmanship. I appreciate when artists have received classical training in jewelry design or goldsmithing. Not because I’m claiming that innovations in the field of jewelry design are threatening ancient know-how, but because constraining oneself to a discipline as demanding as goldsmithing produces a certain type of individual and artwork. The traditional approach of making things mostly by hand implies at once a sense of humility and a strong personality. As a craftsman, you can remain the slave of technical skills during your whole life, just repeating the lessons of your peers. But when you’ve learned traditional know-how and grow as an artist, and develop your creativity to such a level that you manage to challenge your medium and invent your own language, this really attracts admiration. It’s not the easiest way to address jewelry design.

The discipline of craftsmanship often produces generous human beings with profound motivations. These are the people I’m glad to fight for. I wouldn’t be able to advocate for something that I don’t like or by which I’m not convinced. This opinion can sound subjective, but a gallery is like a collection. It necessarily reflects the sensibility of a person. Its goal is not the same as that of an institution or a museum, which aims to provide a wide and exhaustive panorama.

Second, I would say that I’m equally interested in narrative- and material-focused approaches, provided they convey a fundamental message or tell a story. I guess my only reservation would be toward pieces that demand too many comments and explanations, and that don’t have enough visual and material density to speak for themselves.

Third, as far as the curatorial process is concerned, I would say that there are no rules. I always proceed through analogies. I feed myself with books, exhibitions, and viewings (movies, series, websites) and suddenly things simply aggregate, connect to each other in such a way that they start a discussion. Sometimes it’s the desire to confront two artistic universes in the same room simply because aesthetically they’re connected and create something beautiful and harmonious, thus creating an original experience for the viewer.

Sometimes it’s more about creating a debate, or polyphonic conditions of communication around a common theme.

How many exhibits does the gallery host annually?

Céline Robin: Once again, there are no rules. A few years ago, I promised myself not to ever organize a show unless it was relevant or necessary. I think that we’re over-solicited and force-fed exhibitions, shows, movies, etc. We receive more information and images than we’re able to digest, and I’m not really sure we actually get something positive from these experiences. We’re urged to see, to read, to be part of things, and most of all to take pictures of these experiences to share them and declare to the world, “I was there!” I don’t want to consume art, and I claim the right to take time.

Some events can be planned months or years before, especially when you wish to present original and new works like for the Triptych exhibition, which will take place during the Parcours Bijoux in October. For this occasion, the artists—Zoe Arnold, Lisa and Scott Cylinder, Robin Kranitzky and Kim Overstreet, Asagi Maeda, Barbara Paganin, and Robert Mazlo—have accepted to play the game, and they’ve created brand-new works to fit the theme.

Sometimes you simply seize an opportunity and create an event from scratch. These situations often prove to be the most fruitful, with an incredible energy and generosity. Our current exhibition, Holy Tools! (September 7–30, 2017), happened this way. In March, during Munich Jewellery Week, we stumbled upon the work of Sandra Llùsa, Clara Niubò, Carla Garcia Durlan, and Maria Diez Serrat, the four members of the Barcelona-based collective of art jewelers who call themselves Quars d’una. Their exhibition entitled Sense Mesura literally caught our hearts and minds. During the following weeks, their work became the base of the September group show.

Their interest in tools met the concerns of these other artists, who joined the adventure: Lisa and Scott Cylinder, Guillaume Delaperriere, Juanjo García Martín, Robert Mazlo, Xavier Monclùs, Jo Pond, Katja Prins, Fabrizio Tridenti, and Gabi Veit.

A descriptive paragraph on the website mentions exhibiting works from various disciplines as “encouraging a transversal and humanist dialogue between artistic mediums.” Can you elaborate on this statement and how it translates in your curatorial approach?

Céline Robin: This is the key of my engagement in this adventure: the will to erase boundaries, categories, and hierarchies of any kind, especially when it comes to art forms, humanities, the sciences, and the “good taste police.”

We often forget that goldsmithing is the mother of all arts. Many masters of the Renaissance learned their art in the workshops of goldsmiths. Among others, Andrea del Verrocchio was the master of Francesco Botticini, Perugino, Leonardo da Vinci, and Lorenzo di Credi. Brunelleschi was a goldsmith and yet built the dome of Florence’s cathedral. Albrecht Dürer was trained as a goldsmith in his father’s workshop. There was a time when jewelry-making opened wide the doors for other disciplines and wasn’t underrated as a manual activity. This is why I’m not comfortable with the jewelry-centric approach, which is quite recent. I consider jewelry one of the few art forms capable of embracing the whole spectrum of human experiences—hence my frustration at the difficulty of having it accepted and regarded as a genuine art. Art jewelers have intentions that go beyond ornamental considerations. They’re artists who happen to be jewelers. Why should we ostracize them? Why not let them interact and dialogue with other artists who share the same concerns?

But that’s not all. When talking about jewelry, you address issues and disciplines as diverse as art, craft, technology, fashion, psychology, history, anthropology, economy, philosophy, literature, and medicine, among others! Jewelry is a wearable art. Its singularity brings about so many options of comprehension that it seems narrow-minded to reduce it solely to the artistic realm.

As an example of this approach, I invited Guillaume Delaperriere to participate in the Holy Tools! exhibition. He’s showing a video installation entitled Dharavi Orchestra. As soon as I started working on the exhibition’s theme, his video just imposed itself as the most relevant counterpart to the jewelry. It added a sense of music and rhythm, which is inseparable from the manipulation of tools. This video captures the sound and effect of the repetitive task of craftsmen, this kind of trance that is inherent to their work. His point of view is like a behind-the-scenes of the jewelry pieces: What kinds of feelings do craftsmen, and among them, art jewelers, experience during their task? How does the rhythm and sound of tools affect their state of consciousness? Why do craftsmen enjoy working with their hands so much? It’s difficult to answer these questions and to express emotions and feelings of this nature through words.

Unique, custom-display furniture is among the standout features of the gallery. What inspired these unique designs, and how does their function explicitly serve the display of contemporary art jewelry?

Céline Robin: The starting point of our reflection was to create display furniture that would revive hidden, primitive, and universal emotions related to jewelry. Among these archetypical images was the emotions felt by children secretly opening their mother’s jewelry box (and eventually trying the jewels on and looking at themselves in a mirror), generally in the parent’s bedroom. Or the discovery of the pirate’s treasure hidden in a submarine cavern.

I suppose these are emotions that have a lot to do with the voyeur’s pleasure. You look at something you’re not supposed to see, and you actually watch it. In our daily lives we walk by many things: landscapes, people, objects, and images. However, we hardly watch them. In the gallery, we wanted to engage the viewers to make an effort, to closely watch the object hidden inside the box, and to reward this effort with something really special.

During brainstorming sessions, Robert Mazlo evoked a childhood memory. I remember this moment very well. He talked about the hawkers walking from one village to another in the mountains during summer in Lebanon. He described how they carried wonder-boxes on their back and let you watch some animation or short movie for a coin. When he talked about this very special memory, you could feel the fascination he had experienced at this very moment, and we focused on the means we had to convey and capture the memory through a piece of furniture.

We worked on these modules while keeping in mind the moveable camera obscura and the wonder-boxes. They had to be autonomous, modular, and nomadic. Actually, the gallery’s furniture displays revive the memory of the magic lantern and of dioramas. They allow a lot of fantasy because you can stage the jewelry, create a whole environment around it. Or not. Robert Mazlo had the idea to customize each side of the box (like the removable panels of a magician’s box) with different holes. You can find some scars, mashrabiya, glasses, and magnifying-glass-like holes thus modifying your perception of the object.

It can be very playful or completely crippling. Some people engage in the process with spontaneity, others remain completely paralyzed. It challenges one’s curiosity and ability to let it go. And at the same time, it turns your perception into active looking. You’re not obliged to watch—you decide to.

What words of wisdom do you have for early- or mid-career jewelry artists or aspiring curators who hope to work with art jewelry?

Céline Robin: I guess the only bits of advice I can give are those I apply to myself:

- Don’t take things for granted.

- Avoid trapping yourself into a “recipe.”

- Work, work, work.

- Keep asking yourself, “What makes my work relevant? Why should I make it and what does it bring to the debate?”

When I was a student in archeology, one of my professors told us: Do not seek answers. Only relevant questions are important.

What are some notable media you’ve encountered lately—books, articles, films, music, etc.?

Céline Robin: I always read several books at the same time, mostly essays. I’m currently reading The Hero with a Thousand Faces, by Joseph Campbell, and Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent, which, I’m ashamed to admit, I had never had the opportunity to read before.

I recently discovered the writings of Lewis Mumford and highly recommend Art and Technics, which has become one of my favorite bedtime readings, along with The Forge and the Crucible by Mircea Eliade.

Having a long-lasting fascination for the subject of the representation of death and memento mori in art, I also loved Space of Death: Study of Funerary Architecture, Decoration and Urbanism by Michel Ragon. It explains how our relationship to death shaped our towns and their architecture, and provides plenty of information about the history of Parisian cemeteries (among others) and our royal necropolis. This book changed the way I look at Paris.

For a couple of years, I’ve also been collecting books and publications about the work of Joseph Cornell, who is, for me, one of the most inspiring artists of the 20th century.