Susan Cummins: For those that haven’t visited you in Melbourne, could you please give us a history of the gallery and its physical location and qualities?

Katie Scott: Mari Funaki opened Gallery Funaki in 1995. She had recently graduated from the gold and silversmithing program at RMIT and wanted to establish a space that would show what she considered the best of international contemporary jewelry – pieces that hadn’t had an audience in Australia before – and show it in a way that really did the work justice. She also wanted to promote Australian jewelry in this context, placing it beside and showing its equality with the international movement. The gallery is located in a small laneway in central Melbourne, an area known for its culture and history. It is a small, narrow space fitted out very simply with two long shelves as the exhibition space and a series of drawers in which pieces are kept. Mari felt it was important that the jewelry shouldn’t be behind glass but accessible to the hand and eye. People can really examine and interact with jewelry here in a way they can’t do anywhere else.

Susan Cummins: For those that haven’t visited you in Melbourne, could you please give us a history of the gallery and its physical location and qualities?

Katie Scott: Mari Funaki opened Gallery Funaki in 1995. She had recently graduated from the gold and silversmithing program at RMIT and wanted to establish a space that would show what she considered the best of international contemporary jewelry – pieces that hadn’t had an audience in Australia before – and show it in a way that really did the work justice. She also wanted to promote Australian jewelry in this context, placing it beside and showing its equality with the international movement. The gallery is located in a small laneway in central Melbourne, an area known for its culture and history. It is a small, narrow space fitted out very simply with two long shelves as the exhibition space and a series of drawers in which pieces are kept. Mari felt it was important that the jewelry shouldn’t be behind glass but accessible to the hand and eye. People can really examine and interact with jewelry here in a way they can’t do anywhere else.

Katie Scott: Gallery Funaki was the first gallery to show Australian jewelry in an international context and in a gallery space rather than a shop. This elevated Australian jewelry in the eyes of the public and, because the gallery quickly established such a significant reputation overseas, international artists and collectors appreciated the quality and originality of Australian work in a new way too. Important Australian artists like Carlier Makigawa and Marian Hosking had significant exhibitions early on and their involvement meant the gallery had a reputation for excellence right from the beginning. Mari also took Australian work overseas and promoted it in centers for contemporary jewelry like Munich and Amsterdam. Exhibitions such as Delicate Works at Galerie Ra, showing the work of Mari Funaki, Mascha Moje and Marian Hosking, were very important moments in the promotion of Australian jewelry to the world.

How did you end up running the gallery? Are you now the owner?

Katie Scott: I started working at the gallery during my third year at Monash University in 2005 and gradually took over the day-to-day management of the business as Mari devoted more time to working in her studio. Mari and I worked very closely together for five years and towards the end of her life she asked me to take over the gallery. I’m now the owner and director.

Katie Scott: I took a fairly circuitous route to get where I am. I worked in design, administration and event management before starting a Fine Arts (metalsmithing) degree at Monash University, under the supervision of Marian Hosking, Mascha Moje and Simon Cottrell. After graduating in 2006, I worked as part time as a jeweler and also worked at Gallery Funaki.

Can you describe the aesthetic vision of the gallery under Mari Funaki? Have you maintained the same vision?

Katie Scott: Mari had a very clear and uncompromising vision for both her gallery and her own art practice. She knew what she liked and what she didn’t – it was a subjective vision and unapologetically so. She had an extraordinary eye, and could pinpoint within seconds of looking at a piece what its strengths and weaknesses were, why it would or wouldn’t work in her gallery.

What was important to Mari was that jewelry should have a clear concept and a sensitive approach, that appropriate materials be chosen and manipulated with technical skill. She often said an artist doesn’t need to say something entirely new, but they have to say it in their own original way. Clear authorship and clarity of intention were central to what she looked for.

Obviously, Mari’s exacting eye made continuing her work a fairly intimidating prospect. It’s inevitable there will be shifts and changes as time goes on, but having known and worked with Mari so closely over a number of years, I’m confident that can I honor her vision while bringing my own identity and vision to the gallery. I’m happy to say we’re going from strength to strength!

Blanche Tilden: I began studying glass and jewelry in 1988 when I was nineteen, at Sydney College of the Arts. Originally I was interested in becoming a glass blower, but as I progressed I became more interested in making jewelry and I began to enjoy the challenge of combining different materials in new and innovative ways. To follow my interests in both metal and glass, I undertook further study at the Canberra School of Art and began to use flameworked borosilicate (pyrex) glass components in combination with metal parts made of titanium and aluminum to make necklaces. A major influence at this time was Johannes Kuhnen. After completing university, I received a government-funded traineeship, relocated to Melbourne and worked for two years with internationally recognized goldsmith and designer, Susan Cohn.

The combination of all the different approaches and philosophies of many teachers and mentors over this time have inspired me to pursue my own contemporary jewelry practice. I have travelled to Osaka, Japan to work with jeweler Makiko Mitsunari and to Seattle to work with glass jeweler James Minson, as well as to study at the Pilchuck glass school. I now have a full time practice based in Melbourne.

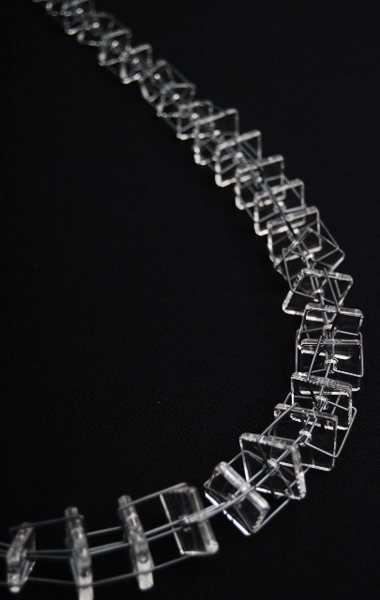

Blanche Tilden: For a long time I have been interested in the history of technology. The rich visual language of machines, the smaller parts of a machine – cogs, sprockets, rivets, chains – have been a constant source of inspiration. The building constructed to display the mechanical achievements of the Industrial Revolution in the Great Exhibition of 1851, London, was the Crystal Palace. The Crystal Palace is considered to the building that signaled the beginning of modern architecture. Constructed like a giant jigsaw from premade panes of clear glass and sections of cast iron, simple elements were repeated thousands of times in the construction of this iconic building. Most examples of the built environment can be broken down into combinations of simple elements such as squares and rectangles: a wall is made of bricks, a skyscraper is a repeated pattern of glass windows. I have observed these elements in their simplest forms in the built environment and drawn on these observations to develop a series of necklaces for the exhibition Wearable Cities.

Blanche Tilden: The titles of each group of necklaces give a clue to their inspiration. The Palais series relate to the Palais des Machines, built for the International Exhibition, Paris in 1889. Another structure erected for this event was the Eiffel Tower. The Paxton series is named after the Joseph Paxton, the architect who designed the Crystal Palace. The Brunel series pays homage to the English engineer Isgard Kingdom Brunel and uses blackened square section silver tube and small rivets to evoke the materials and construction methods of his time – cast iron components held together with thousands of hand made rivets.

Do you think of these necklaces as ‘a sort of talisman for a contemporary nomadic life’ as Anne Brennan suggests in her text for your invitation?

Blanche Tilden: We live in a time that is rapidly changing due to digital technology and globalization. Treasured handmade objects take on new significance as we are swamped by a seemingly endless choice of cheap consumer goods that work badly and then break. These necklaces capture a nostalgia for an era when everyday objects were made with care, were repairable, could be relied on and where objects such as jewelry were heirlooms that could be treasured and passed on.

Blanche Tilden: Two books from the series Architecture in Detail, published by Phaidon, were of particular significance: Crystal Palace, by John McKean and Palais des Machines by Stuart Durant. These books are filled with detailed descriptions of the design and construction of these buildings, as well as fantastic photos of each structure.

What music do you like to listen to and do you have a current band or song you can recommend?

Blanche Tilden: I listen to different types of music, depending on the type of work I’m doing – something with strong vocals like Adele or Everything but the Girl when I am designing and then house music, even 1970s disco when I am making the thousands of components that I build into necklaces – something with a driving beat to keep my making speed up!

What museum, gallery or shop do you frequent in Melbourne?

Blanche Tilden: There are some fantastic galleries and museums in Melbourne. The National Gallery of Victoria is close to my studio, and it is currently exhibiting Unexpected Pleasures: The Art and Design of Contemporary Jewellery, which is an inspiring exhibition of international contemporary jewelry, curated by Susan Cohn. Gallery Funaki is also a source of inspiration and the place to see the best contemporary jewelry in Melbourne.