Anna Lindsay MacDonald, a jewelry artist based in Canada, explores a multitude of paradoxes. MacDonald examines the reverence for tradition and allure of luxury versus the disdain for commercial pandering to the masses. She explores concepts of technology with an emphasis on the hand made. She imagines herself in the future, looking back at the past. With all these contradictions and extremes, one might be a little apprehensive about the outcome. But for her show, Re: Halcyon Dream, at L.A. Pai Gallery, MacDonald pulls together all of these concepts into a dynamic and exciting collection.

Jessica Hughes: Can you tell us a bit about your background and how you got involved in art jewelry?

Anna Lindsay MacDonald: I never thought I would study jewelry in school. I started out in sculpture. Then I learned that NSCAD University (Halifax) had a very strong jewelry program. I enrolled hoping to gain confidence in technique and design. From there, I pursued metals for three years as a resident at the Harbourfront Centre (Toronto) and then obtained an MFA in designed objects from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Can you explain the title of your show, Re: Halcyon Dream? Anchored in Greek mythology, the terms now refer to a short spell of peace and calm in the midst of adversity. Does this apply here, and does it describe a mythological past for you?

Anna Lindsay MacDonald: I love nautical history, so I was interested in the myth of Alcyone. This period of a calm sea I liked as a metaphor for a time before technology changed the idea of authorship in craft. I link the idea of halcyon days/dreams to an imagined intersection between past and present, and to finding a commonality between art jewelry and luxury jewelry. The title indicates that the work is a reference to a dream of longing or nostalgia. In this case, since I situated my perspective 15 years into the future, the nostalgic sentiments are for the present.

It’s very rare that we find an art jeweler using the influence (or admitting to using the influence) of fashion jewelry in their work. What made you decide to explore and reinterpret this concept?

Anna Lindsay MacDonald: We are constantly asking ourselves what luxury is, and certainly some of the best art jewelry throughout history deals with this question.

As students we are taught to have reverence for the luxury houses, but at the same time reject them. The scope of these companies is so complex, I think it’s impossible to understand them clearly from the outside. However, mutual respect for a beautifully made thing should be universal.

The hook of the Chanel quilt texture, the Cartier nail … I’m not immune to those things. I wanted to tap into that language of luxury, but ultimately to create something none of those companies would ever produce.

As artists I think it’s right for us to be critical of the cult of luxury. At the same time, it was ingrained in me during my time in design school that your design is lacking if few can engage with it or think about it. If nobody wants to wear your piece, where does it go? Perhaps it’s in a textbook or in a collection, which is great, but shouldn’t ideas become part of a common language? How do we do that?

In your work, you seem to oppose luxury brands’ nostalgic reverence for the past with our current fascination with technology and exploration of the future. Is your point to embody those contradictions, to resolve them, or to amplify them?

Anna Lindsay MacDonald: A commonality in jewelry marketing is the idea that a luxury object is made by one person or a small group with secret techniques handed down through history. I am interested in what we will see through this nostalgic lens in 2030. “Amplify” might be a good word, as I am using exaggerated marks of the hand in tandem with a tech aesthetic.

Although you reference technology and computer-aided design, you made everything solely by hand. Why was this important to the work? Why not embrace the technology? Why, in fact, pay homage to a nostalgia for the handmade that you critique?

Anna Lindsay MacDonald: I look forward to craftspeople using both technology and hand skill going forward, and I hope to be among them. For this body of work, it was my goal to try to replicate something a computer would produce, and then push away from that with elements that suggest other modes of creation. I wondered if it would be more effective to make something made by computer look made-by-hand, or vice-versa.

There is a density to something made only by hand, and I wanted to explore that quality with a tech aesthetic to see if I could make something that appeared to be out of sequence and without context.

You use a very tight palette of black and whites in both your work and your photography. Can you tell us about your motivation behind this “no frills” approach?

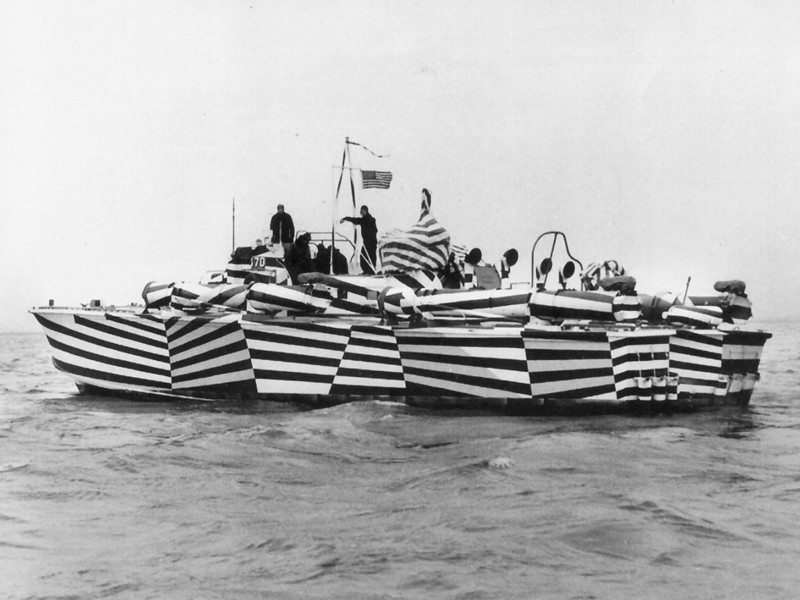

Anna Lindsay MacDonald: I like to use references to strange technologies in my work. The black and white started as an exploration into dazzle camouflage. It extended into the photography via a piece of black velvet. The context changes when an object is photographed on velvet. I think it’s considered dated, but it’s precisely these types of references I’m interested in using.

I use tiny elements of color as well. Several times I’ve mixed enamels to try to re-create a Tiffany blue.

It’s very exciting to see an artist extending the concept of the work past the actual pieces to also consider the photo layout. Can you explain “flat lay” and why you decided to shoot some of the work in that environment? Once again here, you reenact something—commodity fetish in this case—that you criticize in your statement. Are you not worried that your audience will miss the critical part?

Anna Lindsay MacDonald: The “must-haves” section of fashion magazines was always my favorite. In the flat lay, an editor will curate a group of objects in a photograph to create a narrative, and ultimately to create a desire in the reader. I still love them, but I also know they are most often nonsensical.

I reenact the fetish, yes. I do participate. However, I also inject a notion of absurdity. I hope a viewer might become conscious of this distortion, and perhaps made aware that there could be alternatives to consumerism.

Another aspect of your recent body of work is its reference to measuring devices—dials, quadrants—under the guise of decorative wire and latticework. There is an old history of technical objects (from the 17th to the 19th centuries) being made by craftspeople, and sporting some attributes of applied arts objects. Is this a conscious reference? Are you interested in producing objects that look as if they could be technological?

Anna Lindsay MacDonald: I am interested in how data and information have impacted our history of ornament, in how a lace doily could be a dial or a measuring device.

I am often looking at visual data—that which is designed for us to understand and interpret; maps, charts, and that which isn’t; pixels, binary code. I think a reference to gadgets is a byproduct in dealing with those languages.

Have you read or seen anything of interest lately?

Anna Lindsay MacDonald: Home-Made: Contemporary Russian Folk Artifacts, by Vladimir Arkhipov; Cleopatra, by Stacy Schiff; and Dead Wake: The Last Crossing of the Lusitania, by Eric Larson.

Thank you.

Work in this exhibition ranges from CAN$260 to $1,000 (US$197 to $760).

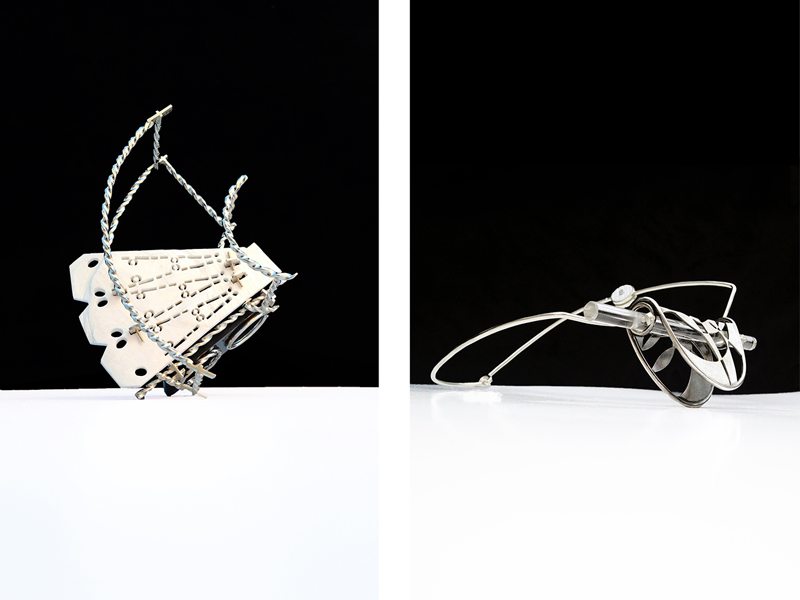

INDEX IMAGE: Anna Lindsay MacDonald, brooch, 2014, sterling silver, acrylic, freshwater pearl, enamel, 90 x 90 x 15 mm, photo: artist