Marjan Unger has been involved with the Dutch jewelry scene for a very long time, performing as a thinker, a curator, a professor, a historian, and a collector. Many of these roles are coming together as she prepares for the opening exhibition of the collection she has given to the Rijksmuseum. Along with the exhibition comes a catalog, and a symposium as well. I asked Marjan and Suzanne van Leeuwen, the exhibition curator and conservator at the museum, some questions about the collection and the process of giving it to the Rijksmuseum. Their responses are fascinating.

Susan Cummins: Marjan, I know you call yourself a Material Girl and that you’ve collected jewelry for a long time, but can you give us an idea of how you got started down this path?

Marjan Unger: I’m a true baby-boomer, born exactly nine months after the end of World War II into a warm, middle-class Dutch family. Nothing special about that; an English friend once remarked, “the Dutch practically invented the middle class.” Special occasions like weddings, your 18th birthday, a degree, or an important step in your work were marked with the gift of a piece of jewelry. Often, you had a say in the choice. That’s a good starting point for realizing what role jewelry can play in people’s lives.

As a curious person, I wanted to live in my time. I have worked in fashion and happily took jewelry in my stride. Those little, wearable objects started to fascinate me, both for their materiality as well as their meanings. But it took me a long time to find out what my talents are. Rather late, I started to study art history and found out that I’m a storyteller, able to see things, analyze them, and write about it.

It was only when I started research for my book on Dutch jewelry in the 20th century that I really became a collector of jewelry, because no museum or other public institute had collected Dutch jewelry from 1900 ’til about 1965. For a small country, a lot of museums for modern art have collected jewelry from the late 1960s on. That’s the period that I’ve been part of. As editor of design magazines, and an art history teacher at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy, and head of the master courses in the applied arts at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam, I’ve been in the midst of developments in jewelry design or more generally in culture both in- and outside the Netherlands. For example, I have happily worn work that I bought from my students and I’ve followed them in their professional developments.

You gave your jewelry collection to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Why did you choose this particular museum for your collection? What was the process you went through to place your collection there?

Marjan Unger: The decision was made in the flick of a second. It was summer 2008, I was sitting in the garden, and I immediately realized it was a good idea, because it was a perfect fit. Then the Rijksmuseum was being renovated, so it was an uncommon choice. Until then, their collections on the whole were limited to about the year 1900, including their jewelry collection. I knew they wanted to take on the 20th century. Other museums with jewelry collections were not interested in jewelry from before 1965. With my book on Dutch jewelry from the 20th century, it was probably the best-documented collection the Rijksmuseum has ever received. In 2008 and 2009, I was working on my thesis, Jewellery in Context. Together with the staff of the museum, my husband and I decided to publicly donate about 500 pieces of Dutch jewelry on the occasion of my doctorate on March 17, 2010. That was a good move. Even quality newspapers published articles about my jewelry in their scientific pages.

Around 2012, Wim Pijbes, the then-director of the Rijksmuseum, and Dirk Jan Biemond, its curator for metals—especially precious metals and jewelry—engaged me in the plan to make a publication on jewelry, based on my thesis, with the jewelry collection of the Rijksmuseum and all their other collections as its main source. Their liberal stand on copyright made this a not-to-be-missed opportunity to write a book on jewelry and its many-faceted contexts. My problem was that it seems to be easier for me to write a completely new text than rewrite an existing one!

You say in the introduction of this new book, Jewellery Matters, that you were “keen to place jewelry in the context of those who wore it, their culture, and their time…” Contemporary jewelry has often been presented without this context and has therefore floated untethered from anything. It has been spoken of solely in relationship to itself. Why should we look at jewelry in the larger context?

Marjan Unger: Historians have written about jewelry from rather restricted perspectives, with emphasis on the developments in style and a strong preference for the new, the avant-garde. Like in art history, they focused on the makers and prominent historic figures. In writing about contemporary jewelry and especially in so-called “author’s jewelry,” the focus stayed on the new, on individuality and the creativity of the maker. As a material girl, my focus is on the jewelry itself. My main question is, “Why do people wear jewelry?” This question is seldom addressed in publications on jewelry, and in answering that question, you also make clear why people make and sell jewelry, one way or another. The reasons for wearing jewelry can be found in the study of fashion and human adornments. They’re very basic, but they change with the way a society develops in a certain place and style. It’s an approach with much wider parameters and, luckily, in the new book there was every opportunity to make this clear, in word and in image.

A big impulse for my new research was that the museum hired Suzanne van Leeuwen as junior curator for jewelry. She’s half my age, trained as an archeologist and a conservator of jewelry, and has substantial knowledge of materials and techniques. That’s so lovely, to work together with somebody who has the same interest and has a complementary set of skills. Now she’s a gemologist as well.

In jewelry, materials are content. If you look at the history of jewelry and the scope of materials used in jewelry now, materials transmit meaning to jewelry, as they probably do to other artworks as well.

Where do you find jewelry in the Rijksmseum?

Marjan Unger: Everywhere. There’s a lot of jewelry on show. First, there’s a historic line-up of jewelry from about 400 AD to 1970 within the special collections on the ground floor of the museum. Interesting pieces of jewelry, silverware, and other small, beautiful artifacts are to be found in almost all the historic rooms, from medieval times ’til the 19th century. I love it when you can look at paintings, big pieces of furniture, and smaller artifacts next to each other, especially when they have something in common. It makes you look more carefully. This autumn, there are five smaller rooms dedicated to drawings and prints of jewelry. They offer a lovely insight into the way jewelry is designed and presented to prospective clients. There are also prints with a moral message. And for the first time, jewelry will be presented in the rooms dedicated to the 20th century.

Jewelry is an emotional topic, so I wonder how you’re currently feeling about giving away your collection. A little sad? Elated? How do you feel about the resulting exhibition and book?

Marjan Unger: Happy indeed, but I’ve always been my most ardent critic. Maybe you can ask me again when the book is printed and the symposium Jewellery Matters, on November 15, 16, and 17, is over.

The remainder of the questions are for curator Suzanne van Leeuwen. First, can you give us a little background about yourself? What’s your position at the Rijksmuseum? Have you worked with a jewelry collection in the past?

Suzanne van Leeuwen: As junior curator and conservator, I’ve been responsible for the Rijksmuseum jewelry collection since 2014. After an introductory course in art history, I graduated in 2007 with an MA in classical archaeology. I spent many summers in Italy excavating, and during that period my focus was already drawn to small (metal) objects and the stories that they tell about their former owners. In 2009, I started with the Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage program at the University of Amsterdam, where I could further develop my interest in jewelry, materials, conservation, and research. During my internship at the Rijksmuseum, I studied the Renaissance jewelry collection, which became the topic of my thesis.

Marjan introduced me to the world of 20th-century jewelry, for which I’m very grateful. I can’t think of a better mentor than her. The Rijksmuseum jewelry collection is the first collection that I’ve worked with. The diversity in age, historical significance, materials, and artists makes me come to work with a smile every day.

You asked a very good question in the book: “What values can be attached to jewelry?” Is it possible to give a brief answer?

Suzanne van Leeuwen: People’s attitudes to jewels and the properties attributed to them can be deduced from the basic reasons why people all over the world have made, sold, worn, inherited, admired, and studied jewels, as well as altered, faked, squandered, destroyed, stolen, and reviled them. In Jewellery Matters, Marjan has defined six universal values to which every aspect of the study of jewelry can be traced back:

- the cultural value

- the historical value

- the social value

- the emotional value

- the material value

- the financial value

Can you talk about how you used recent developments from the study of fashion and clothing as guidelines for your art historical approach to jewelry?

Suzanne van Leeuwen: Like the study of jewelry, the study of fashion and clothing is indebted to art history, but it has a longer tradition. The historical development of fashion and clothing was recorded before jewelry, and this provides a welcome context. Looking at developments within fashion theory, the study of jewelry is broadened to include visions from psychology, sociology, and economics. This wide context allows us to look at jewelry from different perspectives and general cultural developments.

What was the process the Rijksmuseum went through to accept Marjan Unger’s collection?

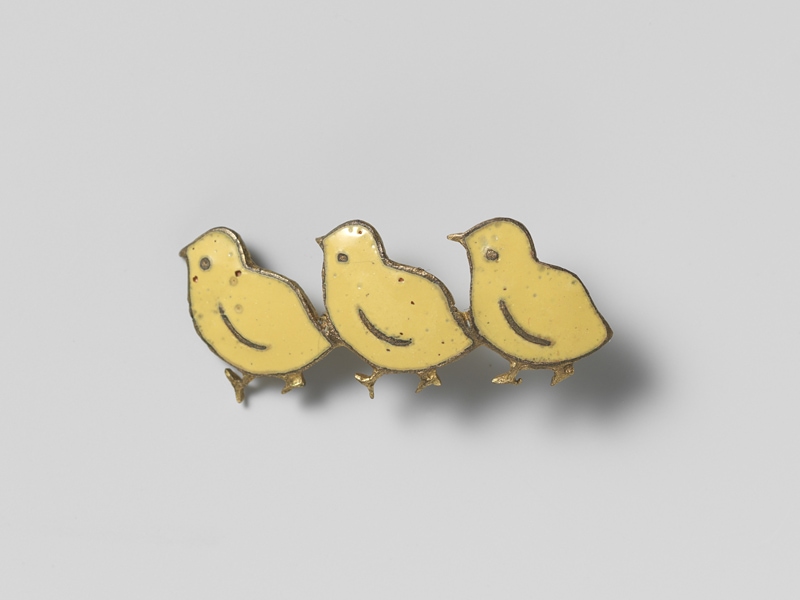

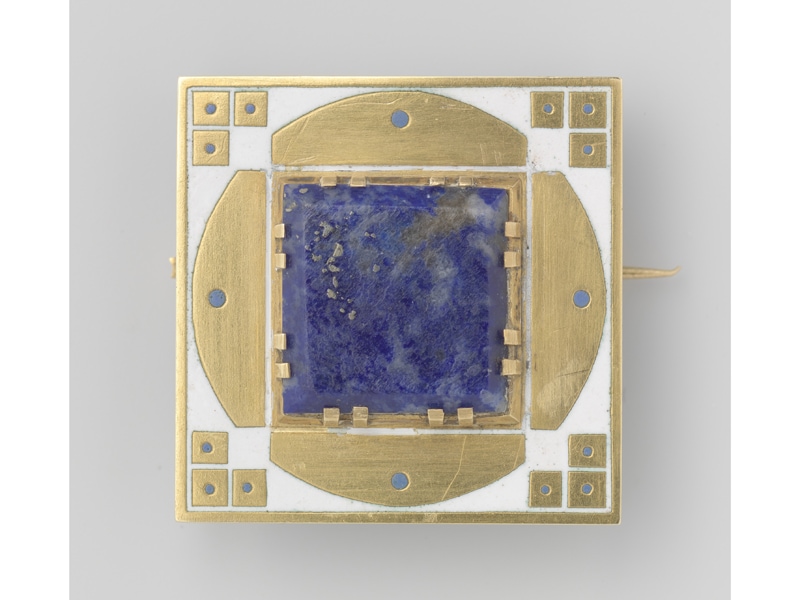

Suzanne van Leeuwen: The Unger collection was accepted by the Rijksmuseum to mark the occasion of Marjan receiving her doctorate in 2010. A considerable part of the donation was already featured in her 2004 book, Dutch Jewellery in the 20th Century, a standard publication when considering Dutch jewelry. The individual perspective that formed this collection has played a very important factor for the Rijksmuseum to accept some 500 pieces, ranging from modest enameled brooches to work from famous Dutch designers from the 1960s onward. The Unger collection has opened doors within the Rijksmuseum that extend our collection policy. We recently acquired a handmade aluminum neckpiece from Emmy van Leersum that was featured in the famous 1967 fashion show in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

After this exhibit comes down, will more of the Unger collection be exhibited in the museum, and what does that depend on?

Suzanne van Leeuwen: The presentation of a small selection of the Unger collection in the galleries of the 20th century is a promising first step in introducing our public to modern jewelry. I hope that we can show more in the future, either in our permanent exhibition or imbedded in a larger exhibition dedicated to jewelry.

Please tell us about the symposium you have planned on November 15–17 in conjunction with the exhibition. How did you decide who to invite and what the program should be? Who do you hope to appeal to? And what do you hope to achieve?

Suzanne van Leeuwen: When we were working on the book, hosting a jewelry symposium seemed an ideal way to share our multidisciplinary approach to the study of jewelry. Questions and topics that developed during the writing of the book form the basis for the symposium. We used them as guidelines when we were thinking of inviting specific speakers. The speakers come from very different backgrounds, and that’s precisely the aim of the symposium: bringing together both specialists and students from different fields within the jewelry community, making no distinction between antique or contemporary, makers or collectors, student or teachers, art or commerce.

When attendees leave the symposium, we hope that they will be inspired, will have formed new ideas, think about research opportunities, and a have a lot of other questions.

Thank you.

© 2023 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org