Master Metalsmith: Myra Mimlitsch-Gray

September 12–November 30, 2014

National Ornamental Metal Museum, Memphis, Tennessee, USA

The text running down the side of the exhibition title wall reads like a group crit word bank à la 90s graphic design star David Carson. Prefixes dis-, re-, and up- are followed by their corresponding suffixes. A clutch of monosyllabic verbs all start with the letter s. And a grab bag of process verbs round it all out: Conceal, magnify, meld, fabricate, etc.

What they describe are the motives and methods behind the 2014 Master Metalsmith exhibition at the National Ornamental Metal Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. The only institution of its kind in the United States, the Metal Museum is responsible not only for exhibiting work, hosting workshops, and providing services to the community and research opportunities to scholars, but also for identifying emerging metal artists, and in the case of the annual Master Metalsmith exhibition, honoring the most influential in the field.

The function of negating function is noted in her Kohler Skillets and Pone Pans series. Culinary molds are considered a form of folk sculpture: Implementing the molds as a tool yields infinite positives, that, depending on the cook, could each also be imbued with artistic attributes. Affixed to a wall, Mimlitsch-Gray’s cast iron molds frame this idea while calling it off. Formally, the Brat Pans are fun mutant biological multiples hung to dry. Eva Hesse comes to mind. But the post-minimalist leanings found here and in many of Mimlitsch-Gray’s sculptures are more a result of material (molten metal) and the processes an artist encounters in the studio than art-historical reference.

These molds are firmly in line with the American craft movement, and there are others: Silver Decanters, Salt Cellars, and Sugar Bowl and Creamer II are forms inspired by the process of metalcraft. A snapshot of the moment when “craftsperson” becomes enamored with the interplay of concept and form, and how objects bear meaning, and how that maker starts to focus–or get distracted by–a goal other than crafting the thing in the least amount of time to yield the most profit (this, if we are to imagine an craft-art scale, is the definition that would be firmly on left, the earliest definition of a craftsperson’s motives.) Mimlitsch-Gray seals this completely, and literally, in Encased Teapot, which “trapped the object as fetish–form closed in on itself completely, access was reduced to just a few sexy holes.”[1] (!)

Humor permeates the exhibition. It seems so natural to see Pair of Cups full, brimming, and spilling over with the same substance they are made of, although this is clearly antithetical to a cup. “Melting” is used in the silver Molten series (Melting Salver, Melting Candelabrum) simply and elegantly, and in the Conflation series to more grotesque effect. In Chafing Dish, we see something metal (copper), typically used for cooking at low temperatures, appearing melted. Because it’s still recognizable as a chafing dish, it works like a successful knock-knock joke: The chafing dish is funny because you’re not used to a chafing dish being funny.

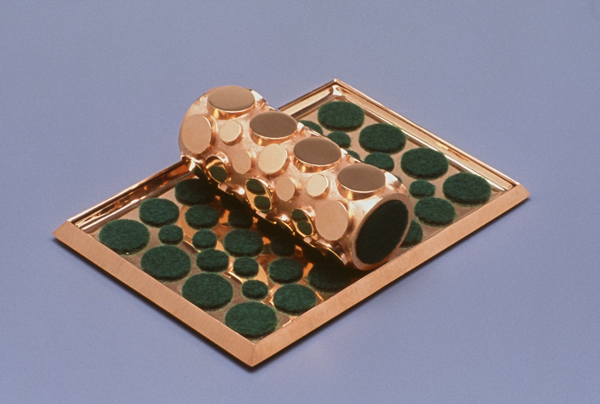

The lay lines of this show trace art and commerce. Now more than ever, “art” is accused of being nothing more than a luxury item for the 1%. It is personal adornment, just as jewelry has always been acknowledged to be. And indeed, my near carnal desire to own Four Prong Standard is also there for Object/Tray Relationship, a piece that implies a function not unlike a desktop Zen garden, while looking nothing like one at all.

Before we had art in America, we had decorative art in America. In 56 works—with equal representation of silver, copper, and gold, followed by ductile iron and brass, two pieces of tin, one bronze (and the Cordial Cups that have the vermeil)—Mimlitsch-Gray uses the traditions of craft to deliver the state of art today.

A catalog titled Staging Form accompanies the exhibition.

INDEX IMAGE: Myra Mimlitsch-Gray, Split Slabs on Floor with Clogs, photo: Neslihan Ulus Lord