Missy Graff: Tell us about the seven deadly sins. Is the temptation or passion to own jewelry one of them?

Emmanuel Lacoste: During the fourth century, the monk Evagrius Ponticus published a collection of eight books, one for each moral transgression that should be avoided so as not to offend God. The eighth sin was melancholy, which would condemn one to wallow in depression. It was removed from the list by Pope Gregory the Great during the sixth century. The final, and still commonly accepted, list of seven deadly sins was defined by Thomas Aquinas during the 13th century. It was supposed to be a frame of reference for the ecclesiastics regarding how to maintain perfect spiritual behavior. All of the possible sins can be identified within this short list.

Emmanuel Lacoste: During the fourth century, the monk Evagrius Ponticus published a collection of eight books, one for each moral transgression that should be avoided so as not to offend God. The eighth sin was melancholy, which would condemn one to wallow in depression. It was removed from the list by Pope Gregory the Great during the sixth century. The final, and still commonly accepted, list of seven deadly sins was defined by Thomas Aquinas during the 13th century. It was supposed to be a frame of reference for the ecclesiastics regarding how to maintain perfect spiritual behavior. All of the possible sins can be identified within this short list.

In March 2008, the Catholic Church announced its will to renew this list and add some social sins, like genetic manipulation, use of drugs, environmental pollution, poverty, etc.

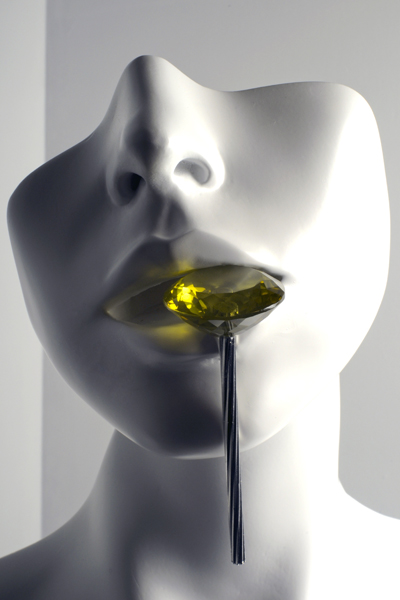

At that time, I found an interest in looking back to the original, primary and outdated list, with a kind of soft irony. In my opinion, these seven sins shape the frame of human weakness because we wouldn’t be what we are without them. These sins are not really forbidden acts, but more what Thomas Aquinas used to call “passions” that submit us to temptation. What underlies these sins is desire, and what kind of object could be a better medium for desire than a jewelry piece?

You say that the “human body is one of the last sanctuaries for individual creativity.” Can you elaborate?

Emmanuel Lacoste: Nowadays, the urge for personalization is everywhere. We want the things that surround us to reflect who we are: house, car, pets, etc., and even immaterial things like our cooking habits, book and movie choices, and the places we want to visit. I think of the objects we possess as an extension of our bodies, and even more so the ones we wear: clothes, jewelry, tattoos. I feel as though individualization and individualism mixed and became the same thing. We have probably reached a summit, but even if individualism is living its last decades, we will still keep going.

How did you begin making jewelry? What led you to use these methods for your more conceptual work?

How did you begin making jewelry? What led you to use these methods for your more conceptual work?

Emmanuel Lacoste: I began making jewelry by accident, or rather I should say “by chance.” After a few years working in the field of marketing and communication, I wanted to learn to “make something with my hands.” I discovered jewelry through a series of events. I met the right people at the right moments. Actually, I met a lot of “good” people within the jewelry world and this is probably why I spent so much time and energy there.

I adopted a conceptual approach quite early. I used to concentrate on technical methods, materials, etc. Later, when I understood that I could put ideas and concepts into such small objects, it was like a key opening a huge and very old door and a monster came out, yelling, “let me tell you a few things!” This was a pretty funny period of my life … sometimes scary, too.

So, if you’re asking what is the reason that I adopted a conceptual approach, I would say … well … I don’t know. Probably an urge to express myself.

Please talk a little bit about the figurative sculptures that accompany each piece of jewelry. Do you consider them to be props or part of the work? Did you make them?

Emmanuel Lacoste: The sculptures are not just bases on which to show the pieces; they are definitely part of the work. When I started this project, I knew that the wearability of the pieces would be subjective: too heavy, too fragile, too strange. But it was important to me that people could see the pieces worn and identify themselves as the wearer. I think that when you imagine yourself wearing a piece, you’re actually already wearing it somehow. This phenomenon works with pictures, but to me, sculpture feels more “real.”

Yes, I made them (helped by a friend) by using pieces of mannequins and re-shaping the parts of the body in order for them to fit perfectly in the positions I wanted.

You mention that “in these pieces the relation between the object and the body is more than just aesthetic, because every piece causes a physical punishment if the person who wears it surrenders to the related sin.” Can you describe this dynamic in one of the works?

Emmanuel Lacoste: We know that if we surrender to a sin, we should be punished (at least if we “believe”). So the pieces reflect this situation. With Envy, for example, the object looks like a mousetrap and the piece of cheese is made of gold. The cheese is what we don’t have and shouldn’t get, but we are attracted, because it’s a (golden) piece of cheese. So, if we surrender to this envy, we will get hurt by the trap, like a (funny) metaphor for a divine punishment.

Can you discuss why you chose to communicate these ideas through adornment as opposed to objects? What importance does jewelry have in conveying your concept?

Can you discuss why you chose to communicate these ideas through adornment as opposed to objects? What importance does jewelry have in conveying your concept?

Emmanuel Lacoste: I discovered art and expression thanks to jewelry. Since then, I have worked with various other media, including objects, installation, sculpture, photography, and performance. I choose to work with the one that best fits the concept I want to address. For the Seven Deadly Sins series, jewelry was obvious because of the desire that this type of object conveys.

You taught a “Wearable Objects” course in the fashion department at Paris College of Art. What are your thoughts on the relationship between art jewelry and fashion?

Emmanuel Lacoste: Jewelry and fashion have an old and obvious relationship because jewelry has been part of adornment for a long time. I won’t discuss what is “art jewelry,” or the differences with “contemporary jewelry,” or whether fashion is an art or not. The question is too long to answer and I have to admit that I’m still not sure about the answer I would give. So I will just tell one anecdote: When I graduated from the AFEDAP (a Parisian contemporary jewelry school), my first job was to work for fashion brands, and especially for fashion shows. I used to make a lot of jewelry pieces that sometimes were worn for only 30 seconds, and sometimes not at all. I realized that these pieces were essentially performance pieces, not very different from my own creations.

Can you tell me about the French art jewelry community? Would you describe it as active?

Emmanuel Lacoste: The French contemporary community is very active, but also very disparate, and sometimes disorganized. Besides their different points of view about the practice itself (how we define it, what are the limits, how we teach it, etc.), people have to face status issues (jewelry is still not considered an art in France) and the historical weight of traditional jewelry. This community is made of very nice and clever people who can overcome their differences and work together. This is what we experienced with the huge 2013–2014 event called Les Circuits Bijoux, that should happen again soon, I hope. What the French community lacks the most is a solid network of galleries. Galleries have a big responsibility: they have to invest in artists, represent them, communicate, educate the public, and also survive commercially. This is not the easiest job.

The image you selected to promote the exhibition depicts an androgynous figure clad in a green gown, holding a cross and wearing a tiara and a large ring. I have to ask, what is the story behind the image? Did you create it for the show?

Emmanuel Lacoste: This image is part of another project I conducted in 2010–2011 with the artist Alexandre Keller and the photographer Mickaël Mohr: the CARNE project. This

consisted of a series of four photographs and a complete set of jewelry.

It involved a particular material: meat. Meat is a metaphorical material used to represent human flesh, and the preciousness of the body. Used in this way, meat generates a disturbing feeling in contrast with the supposed preciousness of jewelry. The CARNE photographs are baroque representations of an old and frightening lady, Vera Berkson, wearing disturbing pieces of jewelry. As these pictures suggest, Vera Berkson has an obscure and uncertain history, and so do the pieces of jewelry. The project has been intentionally thought of as a photographic “portrait” project. The ephemeral material had to be recorded in time in order to capture the fresh and disturbing aspect of the meat jewelry.

Do you have a favorite deadly sin?

Hmm … no, not really. Sloth, maybe … I would love so much to surrender to this sin.

Thank you.