Art Jewelry Forum has just published three reviews, one video, and four Best of articles dedicated to Munich Jewelry Week (MJW): That adds up to eight pieces of writing, out of the roughly 140 we will publish this year. Considering the international breadth of the field, and my own reservations about treating said field as one thing, this is extravagant.

Nonetheless, I now add another text to the others. Most of what was published about MJW favors newness over contextualization and looks at this yearly event with the optimistic excitement of a three-year-old in a toy shop: so many things, so little time (I love everything!). This positive outlook reflects the fact that we consider Munich to be our collective Mount Everest: The assumption is that “making it there” is difficult, that those who do are automatic heroes. Their reward is our blessing. (Exhibiting in Munich is exciting, but (1) the road to “getting there” has actually less to do with artistic practice than with organizational and networking skills and (2) I actually don’t think that exhibiting in Munich is quite the challenge most suppose it to be. But I digress.) The prevalent idea that MJW is a summit has two consequences: We look up to it, and we tend to consider it in isolation from both its past and everything that happens in the rest of the world. Munich is that cool.

What follows tries to buck the trend. I was interested in rereading MJW 2016 in the light of three questions to be found in AJF’s archives, questions that look at the promises and challenges of the field. First, looking at past reviews of MJW, I wondered about what we called the “theatricalization” of jewelry display. Were curators this year more mindful of the distinction between meaningful and invasive props? Second, taking a page from Current Obsession editor Kellie Riggs, I asked myself if this year’s group shows were any better at distinguishing practices from one another than those examples she reviewed. Lastly, looking at this text written by previous AJF editor Damian Skinner, I tried to figure out what the ambitions of contemporary jewelry are today.

Looking at current events through the lens of articles published in the past is something I will be doing more this year. These Briefings are comparative instruments. They mean to track how past practice collides with the new.

Quieter—But Not Quiet

Based on the 28 shows (and countless images) that I have seen, MJW 2016 was “quieter” than the previous three editions. Quieter means less theatrics (think of the moving trains, bulging Spandex walls, or bedroom reconstructions of the past) and, generally, a move back toward the classic “object-on-a-raised-platform” format. (I should note that there were 80 shows in the program. I saw about 40% of them, and a different itinerary would certainly have provided me with a different experience of MJW. )

Minimal setups have a tendency to trip up group shows, and to compound the two challenges they face: lack of space, and a multiplicity of voices. They don’t fare well in comparison with crisper, more focused projects featuring fewer exhibitors. This year was no exception. New Work from the New World, organized by American gallery JewelersWerk (in partnership with Olga Biró) is exemplary of the problem. Some arresting work by inspired makers—Mielle Harvey, Aric Verrastro, Timothy Veske-McMahon—struggled in what can only be described as a hostile environment: a narrow table on which dozen of pieces from a variety of practices fought for domination. Meanwhile, large, melancholy photographs of Italian palazzi lined the gallery walls and leveled anything in the (jewelry) show down to the diminutive economy of flea-market stalls. A more generous space—or a tighter selection—would have rewarded JewelersWerk’s first participation in Schmuck and given this welcome cast of American makers the spotlight they deserved.

Group shows made a better impression when curators were mindful of the need to create discrete divisions between works, or groups of works: Germany’s Upcoming Talents—GUT, a few doors down, did just that. The works from six different schools and academies were arranged on clusters of color-coded plinths. Simple scenographic devices—varying plinth heights, the occasional wall or ceiling hanging—showed that the host, Kinga Biro, had favored attending to the work’s need, rather than applying a cookie-cutter system to every single exhibit. It made the work’s academic provenance clearly readable and carved some space for individual pieces without upstaging them.

Two exhibitions were notable for their attempt at using the de facto insularity of the gallery space to take visitors on an imaginary journey … back to the exhibitors’ country of origin: the much lauded By Royal Appointment, by Dialogue Collective, and the Résidences Paris München exhibition, at the French Institute.

Résidences—a new artist in residence gallery based in Paris—did the clever thing: it reproduced the entirety of the gallery, to scale, in the rather grand salon of the French Institute. A looped film of Parisian street life as shot from the gallery’s front door gave the setup an arty edge (contemporary art’s ongoing flirtation with the insignificant may be to blame here). A number of visitors didn’t notice the film, nor understand that the white line on the floor represented the gallery’s original walls. That didn’t matter much: the unnecessarily tight, inward-facing cluster of hand-made display furniture functioned very much like a bonfire—you were either in or out of its arm-length glow. People huddled there for a bit of warmth and looked at work—or stayed out and looked at the gallery within the gallery as a comprehensive installation. This produced a form of magnified intimacy that was consistent with the field’s dual affiliation to the public and the private, and supported the exhibit’s strong reference to the body.

Although I felt that Dialogue’s “regal” narrative in some instances turned work into politically meek one-liners and obscured its material richness, the setup did impress by its efficient simplicity: Outlines of domestic furniture traced on the wall with black tape provided a self-consciously tentative stage which bolstered the collective’s unpretentious witticisms. Here again, a simple but transformative setup buoyed the curatorial narrative without becoming visitors’ main focus point. In both these cases, uncomplicated, effective devices, enriched by exhibitors’ zealous presence, and generous explanations, wowed visitors. (Dialogue Collective are particularly good at this: By Royal Appointment was nominated by three out of 10 jurors in AJF’s MJW 2016 Best display category.)

The decision to simplify setups on the heels of the more adventurous display strategies of previous years may signal a tacit understanding that louder does not mean better, and herald a curatorial return to a comfy, noncommittal position halfway between the white cube and the shop. When done well, this hybrid position let visitors decide what the work was about, in a guess-what-I-am sort of way. Neither encroaching nor self-effacing, the success of such strategy depended on careful arrangements and edits, and reflected jewelry’s continued allegiance to both the wearable and the sculptural.

On Making Distinctions

Some will argue that the best one can do with group shows is address the primary challenge of providing adequate platforms for diverse works. Still, the fringe jewelry practices of 10 years ago have matured into established genres and added to the field’s expanding repertory of practices. In this context, this noncommittal solution remains a poor tool to address the ever more pressing need to distinguish between them: I was interested in exhibitions that more forcefully staked a claim about the work’s affiliation.

(IM)PRINT left an impression—as seemingly any show which involves the quietly cross-disciplinary Cheng and Brovia couple does. They shared the stage with a powerful cast of like-minded—and, cleverly, not-so-like-minded—people. Silke Fleischer, Yuka Oyama, Lin Cheung, Liesbet Bussche, and Sanna Lindberg (makers who work with installations, performance, participation, or photography) rubbed shoulders with object makers: Göran Kling, David Clarke, Nils Hint, Kasja Lindberg, Niels van der Wouwer, and Hanna Hedman. (Hedman was the instigator of this project.)

What was gained by showing one next to the other? The majority of works deployed contemporary art tropes—obsessive repetition, inventories, absence, the self-reflexive accumulation of marks (removals and additions)—and pulled those works most entrenched in craft into art’s discursive arena. Nils Hint’s very “crafty” squashed brooches, for example, were energized by David Clarke’s studies in defunct functionality and Silke Fleisher’s series of incremental rings. They lent his wall installation a surreal, pictorial character. (Some works did less well: the white-cube environment highlighted the maudlin element of Niels Van de Wouwer’s A Group of Botanical Jewels, and made it look a little meek in comparison to the rest.)

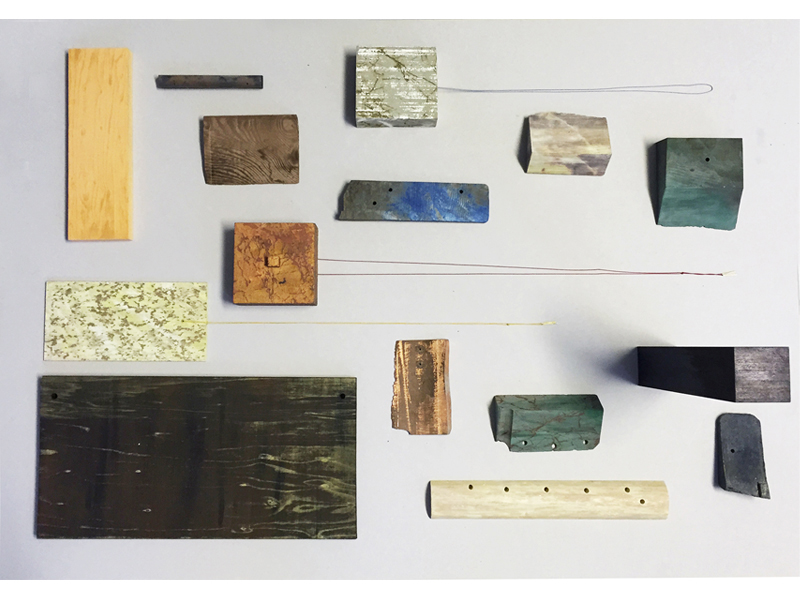

More clearly than any other show I saw, (IM)PRINT spoke of the vernacular of fine art installations: empty space and uncompromising display decisions loomed large, as supported by a cast of pauperized props (photocopies, knock-down furniture, staples). It used a wide repertory of backdrops (plinth, wall, shelf, floor) and fastening systems which intensified, rather than reconciled, the formal differences between artists. The (IM)PRINT Team’s argument—for these small decisions do constitute arguments—is that these multimedia fantasies need to seek modes of presentations that are proportioned to—but occasionally dissonant with—their “natural habitat.” Nicolas Cheng’s placing of 15 blocks of wood and stone look-alikes on a 2-inch-high pedestal anchored his fictional objets trouvés close to the ground—where they come from—but also resonated with Vija Celmins’s seminal inventory of fake rocks. This careful placement summoned art historical precedents—like Celmins—but also referenced the archeological strategy of presenting findings on the ground, in the position in which they were dug out. This in turn highlighted the fakery of these fakes, and lifted them back to ornamental, post-Flintstone status.

Meanwhile, David Clarke had placed his molten cutlery on stand-alone industrial metal shelving across the room: That choice suggested a poor man’s wunderkammer, but also invited the possibility that other cutlery—now sold?—had once populated those shelves. (Clarke’s palimpsestic works often summon absence to deploy their charm.) This simple presentation device referenced the domestic and the commercial, in an evocative, but undecided, way.

These two examples are indicative of the split between those presentations that deliver their sugar to me immediately and those that slow my progress—and reward me steadily when I spend time with them. (IM)PRINT was remarkable because it harnessed the setup to state a definite position about each work, which in turn made the possibility of unexpected kinship much more exciting. In comparison, the nearby exhibition at Vitsœ, presented all the pieces on their 606 Universal Shelving System, a crisp-looking modular system designed by Dieter Rams in 1960. This forced all the exhibited items to negotiate more or less successfully the presumption that this design habitat constitutes: that they were products, or objects playing at being products. The single setup—as one would expect—buoyed the individual works’ agency unevenly.

***

You, dear reader, are probably starting to find my insistence on the “setup” rather tedious, so let me justify it for you: MJW is a sea of things. A sea, I should add, of things you and I have already seen online, or directly in our in-boxes, just before reaching Munich by air, rail, or road. In this context (and in any other context, I would argue), the function of an exhibition is not simply to show things—God forbid—but to provide markers that will activate the work’s singularity, unleash its complexity, amplify its agency (as object, as artwork, as product—it doesn’t matter which). It doesn’t have to be aligned with the artist’s intent—some works come alive when challenged—but it should at the very least make a conscious attempt at situating the work in a field that is both extremely creative and very diverse.

Which brings me to my third point.

On Making Connections

In 2012, Damian Skinner issued a call to overcome the Eurocentrism of jewelry and challenge the binary power distribution between it (Europe) and the rest of the world. Not having a ready solution for this historical problem, he suggested that the most ambitious practices were those that resisted the dominant discourse of jewelry, while being attentive to its long history: by situating practice locally, in what has become a global field (or, as he cheekily called it, the airport lounge of global, contemporary jewelry).

Four years after his writing, I feel the need to extend Skinner’s argument that jewelry go beyond place of origin and conduct implicit conversation with other fields. Contemporary jewelers’ inroads into adjacent fields are so prevalent that it is hard, and not always useful, to meet their jewelry on jewelry terms only—because these “terms” originate both in and outside the specific history of jewelry.

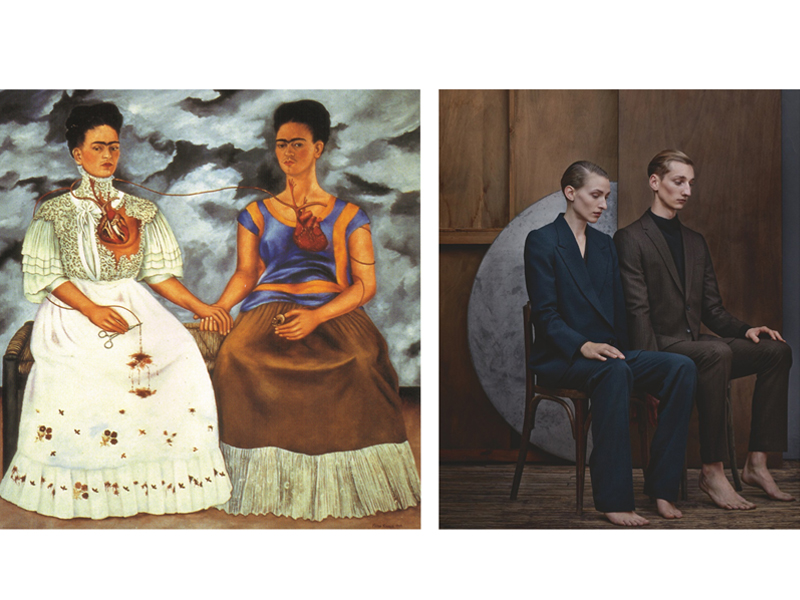

Let me give another example, from IM(PRINT). Hanna Hedman’s prolific œuvre is technically accomplished, thematically coherent, and rooted in the transformative power of worn, physical jewelry. It does not make sense to describe, or analyze, her work as conceptual. One way to make sense of it is through the lens of jewelry’s ongoing flirtation with the talismanic, to which she brings a craft sensibility and a Nordic explicitness. Another way is to pay more attention to her collaboration with photographer Sanna Lindberg and to look at their common output in conversation with other image makers: Diane Arbus, Frida Kahlo, and, closer to us, Julia Hetta. In this group, Lindberg’s minimalism comes to the fore, while the jewelry itself becomes accessory to a visual fiction. I find that Kahlo is their closest kin in this: Like hers, their picture is anchored in an imaginary world of self-transformation, but does not feel quite as transient as a fashion image. (Arbus, meanwhile, has much more grit. Her pathos is not something you can take off and hang, as you would a necklace.) Looking at Lindberg’s and Hedman’s work in this context suggests that their pursuit is an aesthetization of the uncanny; it makes me wonder about the necessity of exhibiting the objects themselves (beautiful as they are) and whether this hybrid practice should have a name.

On Being Different

Cheng’s and Hedman’s work have very different ambitions from one another and demand that we look at them with different criteria. Still, IM(PRINT) managed to juxtapose them in a way that was dissonant in a productive way. In comparison, this year’s Hoffman Prize seemed like an indiscriminate group hug. Stefano Marchetti’s diminutive arte povera proposition looked like it was accountable to other gods of creativity than either the seductive, colorful work of Jelizaveta Suska or Moniek Schrijer’s blunt monument to human (mis)communication. What was gained by rewarding such a diverse group is not clear to me, but may have to do with the general “come in, we are open” policy that characterizes the field. But I wonder if openness is not getting in the way of discernment. I love the camaraderie, but accommodating all these various practices in the same bag is increasingly problematic. This, incidentally, reminds me of a vitriolic comment that was delivered, some years ago, in our comment box:

“The objects exalted by Art Jewelry Forum are the result of a bankrupt arts education system and a train wreck of an economic system. Sure everyone will want to look at a train wreck, but to write about what it has produced as if it had artistic merit is like picking the pockets of the dead passengers and trying to extrapolate meaning from the content. It is meaningless, futile and in poor taste.”

Ouch!

Even though we all tend to meet up in the same railway station, I don’t believe jewelry is actually on a single train, going in a single direction. The commentator’s point, I think, is that differences in practices are too big to ignore, and this signals the road ahead: We must now attend more precisely to jewelry’s diversity, lest our “supportive family” syndrome start stifling the development of distinctive offshoots.