Susan Cummins: Where does the title Vintage Violence come from?

Brigitte Schorn: It comes from John Cale’s first solo album.

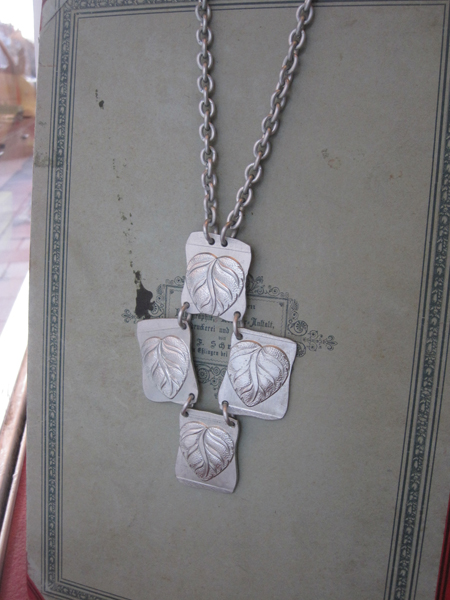

Volker Atrops: Yes, and it is a totally different context, but in our case it fits very well—“vintage jewelry” and “violence” because we pushed the material against all the rules into the extremely heavy, old machines. It took brute force but gentle output.

I know there is a story behind this body of work. Can you tell it?

Brigitte Schorn: Do you mean the story from our first invitation card? The text is now on the announcement of Ellen Reiben’s Jewellers’werk exhibition.

Volker Atrops: Yes, we worked twice a week during the winters of 2012–13 as craft goldsmiths in an historic fashion jewelry company. It was “the big fish eats the small” in reverse. I liked it very much. We would make three or four pieces on machines with tools that were made for mass production. We broke goldsmithing rules as mass-production achivements as well as the codex of so-called “art jewelry” by giving a shit about sculpturbility, artybell authorship. It was pure fun, even if it was extreme cold and lonely in the halls.

Volker Atrops: No, not right. We did not find much jewelry there. What we called treasure and what we found were old stamps, pattern rolls, and forging dies.

Brigitte Schorn: Yes, but with one exception: they had bucket full of aluminium chains that we used.

What kind of metal is it?

Volker Atrops: In the 1950s, they produced fashion jewelry made of aluminium, so we also used that material. Aluminium was first used by Napoleon, while the others had to use only silver cutlery. On festive occasions, the Emperor, the Empress, and certain guests of honor tended to use aluminum dishes to dine. Since aluminum could be produced only in small quantities in the 1880s, it was more valuable than gold. Aluminium is the plastic among the metals. In the late nineteenth century, it was more exclusive than gold, and if you imagine how much energy it takes to produce aluminium, maybe in future it will be like this again.

What processes did you use on it?

Brigitte Schorn: Volker already suggested that the main process was to use the mass production facilities in the wrong way. It doesn’t mean that we got the absolute same identity for thousands of pieces. Every piece was a bit different, even if we did the same operation more than once. We numbered the output 1, 2, 3, 4.

Volker Atrops: We did not have the goal of making unique artist pieces.

How did the original patterns and shapes of the old pieces affect the final product?

Brigitte Schorn: It’s the other way around—the old patterns made the final product. Before we used the pattern machines, there was just a piece of aluminum. The machines gave the material not only a pattern but the form as well.

Volker Atrops: In some works, such as the bangles, the moment we put a decoration on the metal the whole form came into existence. Imagine that wallpaper builds the house.

Did the two of you work together on all the pieces, or are some of them by Volker and some by Brigitte?

Volker Atrops: We work in parallel. It would be better to say we work in one-hour shifts because of our little son.

Brigitte Schorn: We each follow our own ideas or interests, but sometimes one will start and the other one will finish a piece.

Volker Atrops: We took a bunch of half-ready aluminum stuff home to our two little studios where we each finished our pieces.

Can you give me some of your background and describe how you became a jeweler?

Brigitte Schorn: I learned goldsmithing as a profession, then I studied fashion design, and with my partner Sonia Boessert, we established the fashion label Boessert/Schorn. Now, I have gone back to work with metal, but in some cases my interest in textile is still visible, for example in the necklaces, which became two dimentional by putting the chains side by side, like fabric, or the bow brooches. The demand is to use metal, which is solid and long-living, but give it a kind of soft character as if it were textile.

Volker Atrops: I like the miniature and small scale. It is the dimension of ball or a hand, a human one-to-one size. It is not like big sculpture for large public pieces or open space. When I was 16, my friends and I started to make earrings and bangles, piercing each others ears, and so on. The style was something in between punk and glam, my first series. I cut rosaries in pieces and attached them to earrings and necklaces. Two years later, I learned the profession—gold granulation, stone setting, casting, enamel, all that classical stuff. Some years later at the Art Academie, I was able to create common art jewelry styles, but my interest goes one hand to art and on the other to decoration and jewelry. I like to separate these fields, but maybe in my drawings both can come together.

Brigitte Schorn: Contemporary jewelry means, to me, jewelry that fits in our time. That means it has the look of the people and the fashion of the moment. When I make jewelry, I put it onto a dress form or try it myself to decide how it should be.

Volker Atrops: I’m much more fascinated what the people wear on the street, in different scenes, or lets say, in different neighborhoods. The important pieces of contemporary art jewelry mostly look too ambitious to me. They show a special skill or a view or an idea that the author had about art or design. Mostly it looks kind of artificial or displaced when you wear it. It is not very connected to what happens in fashion, music, or new or classical style interpretations that people wear in these times. Art jewelry is mostly for art jewelers—not so much wrong with that, but most developments or crisp new interpretations of good old jewelry does not come from the art jewelry scene.

What have you seen, heard, or read lately that you would like to recommend?

Volker Atrops: Mostly German or local themes, but also some YouTube films from L.A. that I saw in the last weeks touched me because of the situation of how artists with wonderful talents join the world of stardom and kick it into pieces by turning their backs on it: Sylvia Juncosa (“Dead Grip” and friends bands); Mick Farren (L.A. Memorial); and Henry Grimes (whole story).

Brigitte Schorn: In 70-percent of all people in Germany who were tested, have Glyphosat, which is a detectable herbicide.

Thank you.