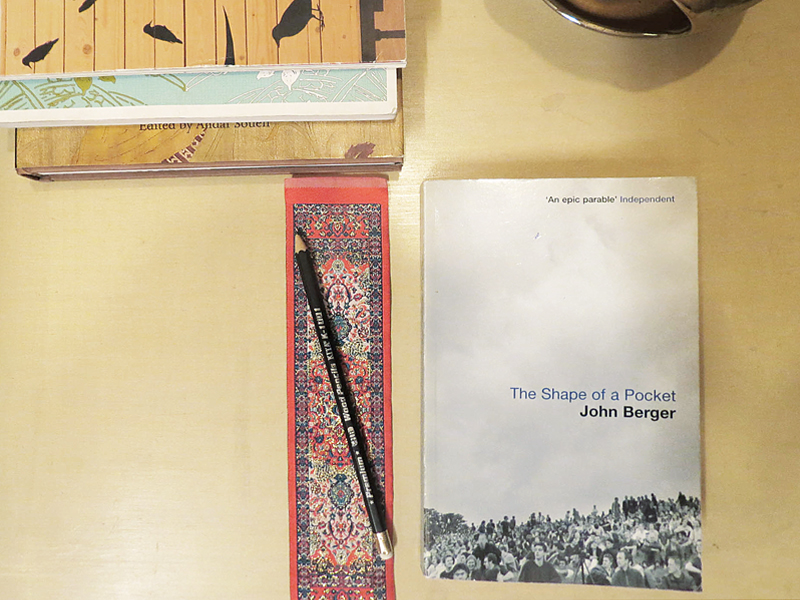

After the publication of this book, Berger described that he “has never written a book with a greater sense of urgency.” This comment resonates with me to this day, as I have never read a book with a comparable level of urgency. Before starting the book itself, I was particularly drawn to its striking cover illustration: Illustrated by Peter Marlow, it has a revolutionary air of truth to it. An infinite expanse of sky stretches to the top of the book cover, with an undulating mass of gray clouds. Below, crowds of people are gathered like pilgrims, as if in an auditorium, settling down to listen to Berger’s arresting text on art and resistance.

Berger, an English writer, art critic, and a painter, is a collaborator of language and voice, looking and seeing, imagination and conscience. And this noble collaboration, for him, is never a binary affair. Rather, it is always triangular. This book was conceived as a “pocket” of resistance against the fabric of inhumanity spun by the new world economic order, in the form of compelling triangular exchanges: “coming together are the reader, me and those the essays are about—Rembrandt, dogs at dusk, an expert in the loneliness of certain hotel bedrooms.” With poetic precision, he has gathered paintings, hotel bed sheets, a crumpled paper in Rembrandt’s studio, to recount their stories on an imagined stage, before their memories are lost to the inertia of odious mainstream politics, the Internet, and reproductions.

And here is where we meet. This, as Berger’s readers know, is the quintessential title of another one of his books. And it is probably the most salient expression of the way he projects his stories. His chapters are meeting places: as tangible as Leon Kossoff’s drawing studio, or as intangible as the changing evening light in Miquel Barceló’s studio.

In the middle of a book, we meet him near the River Po, where he quiveringly outlines the contours of our destiny as “always beside, never in centre, with no clear outline.” And he invokes this through the angles and frames of a character, The River Po, as it appears in Antonioni’s film. Frida Kahlo’s paintings, today, are eclipsed by discourses on feminism or Mexican popular art. But in the chapter dedicated to the artist, he discreetly discovers in her paintings, like an epiphany, her indispensable necessity to paint on surfaces as smooth as her own skin: Masonite and metal, instead of a grainy canvas. And he goes on to describe Kahlo’s tracings on Masonite as a confession of her pain and of being sentient to all that is alive and living.

Berger thinks in climatic terms, smells with the fog, peers through pure beeswax, and writes with indelible cinematic ink. The lives and subjects evoked in Berger’s pages enact and reaffirm their appetites and delusions, allowing us to feel their presence. The presence “which has to be given, not bought.”