When Anvita Jain first proposed publishing an article about one of the most prominent and prolific contemporary jewelry artists from India on AJF, the editorial committee responded with great enthusiasm, but also wanted to start by learning more about the scene in that nation. We therefore asked Jain to prepare a series of texts on art jewelry in India. This first article gives an overview—no mean feat given the size of the country. Also in the works: interviews with top artists.

How can we begin to approach the development of a framework for contemporary and conceptual jewelry in an Indian context? I find myself drifting in the direction of the individual’s response to the experience of adornment and what it can be. I have attempted to put together a set of contemporary artists whose work is made in relation to the collective language of Indian body ornament, filtered through their own consciousness in the context of the global present.

“Defining the ‘contemporary’ and ‘conceptual’ in the context of Indian jewellery and body ornament is a challenge. Adornment that may be avant-garde for one community might be perfectly normal for another. Many forms of traditional jewellery, talismanic for example, perform a conceptual function, sometimes very specific to the individual. After being activated through mantra and ritual, it protects the wearer.”

—Dr. Naman Ahuja, professor of Indian iconography and decorative arts at JNU, New Delhi

The Tradition of Jewelry/Body Ornament in Indian Culture

It’s imperative to establish the significance of jewelry/body ornament in Indian culture. Adornment in India is a way of life. A body devoid of adornment is considered inauspicious. Once decorated with beautiful ornaments, the body becomes attractive and perfect. From birth to death, jewelry is an inseparable part of the human body. Ancient Indian figurines might be devoid of clothing but they are almost never devoid of jewels. The rich and cosmic variety of ornaments in India spans 5,000 years and is spread across 3 million square kilometers. In a population of 1.25 billion, every single person—newborn, young or old, rich or poor, urban or rural—owns a piece of jewelry.

Related: The Do-It-Themselves Movement in Indian Contemporary Jewelry

Related: AJF Hangout in South Asia (scroll to the last video)

Related: The Mystery of Contemporary Jewelry in India

Jewels dispel anonymity by proclaiming status and caste, ethnic identity, religion, and a person’s region of origin. For an Indian woman, jewels are Streedhan: savings or wealth that she receives from her father at the time of her wedding. Sringara, or adornment, is among the 16 rituals of beautification a bride undertakes in preparation of her wedding, comprising ornaments from head to toe. Ornaments, it is believed, transform a bride from a temporal being into a divine goddess on the day of her wedding. This divine alchemical aspect is also important in the case of deities. The gods, an expression of formless ultimate reality, assume an earthly persona, become visible and real through clothes and adornment with fabulous jewels. In this way adornment, or Alamkara, makes the invisible visible. Placement of jewels on various parts of the body also has physiological importance. Ornaments placed on hidden spots at the juncture of veins, muscles, joints, bones, etc., gently stimulate the area, ensuring physical and emotional equilibrium.[1]

Adornment and Contemporary Visual Art in India

Due to their inherent potential to speak of the culture at large, several contemporary Indian artists have employed body ornament as a powerful symbolic language in their work.

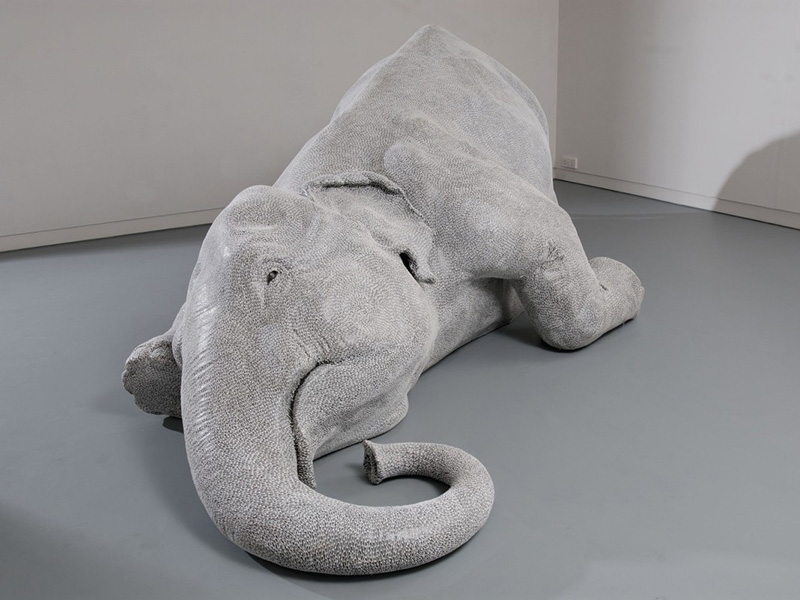

Bharti Kher, a prominent Indian artist, (born in the UK, living in New Delhi), uses bindis as a potent symbol to address many issues and ideas such as gender, social roles, rituals, sexuality, and popular culture of India. Bindi is a decorative mark, essentially a dot, drawn or stuck in the middle of the forehead by Indian women as a celebration of marriage and the ajna chakra, or the opening of the third eye. In Indian philosophy, “bindu” refers to the cosmos in its unmanifested state. Kher explores the symbolism of a bindi in innumerable ways in her works. Her visual language draws immensely from the observation that, at the end of each day, women transfer their bindi from their foreheads onto the bathroom mirror. In a similar way, Kher turns the gaze back at the viewer and creates a sense of turbulence through dynamic compositions of bindis on mirrors. In other surrealistic sculptural works, sperm-shaped bindis adorn the entire surface of a dying elephant, or a whale’s heart.

Anjali Srinivasan, a Dubai-based Indian artist working with glass, often plays with the colors, textures, and form of glass bangles. In her Arm series, she disfigures red bangles, distorting the social associations that come with them. Red glass bangles are part of the paraphernalia of a new bride to celebrate marital union, and as such hold huge significance for new brides in some parts of India. Women show their religious and regional identity and situate themselves firmly in their life cycle by the number of bangles worn.

Shakuntala Kulkarni, Photo Performance: AshokaTowers, Parel, 2010–2012, digital print on rag paper, 71 x 107 cm, image courtesy Chemould Prescott Road, photo: Anil Rane

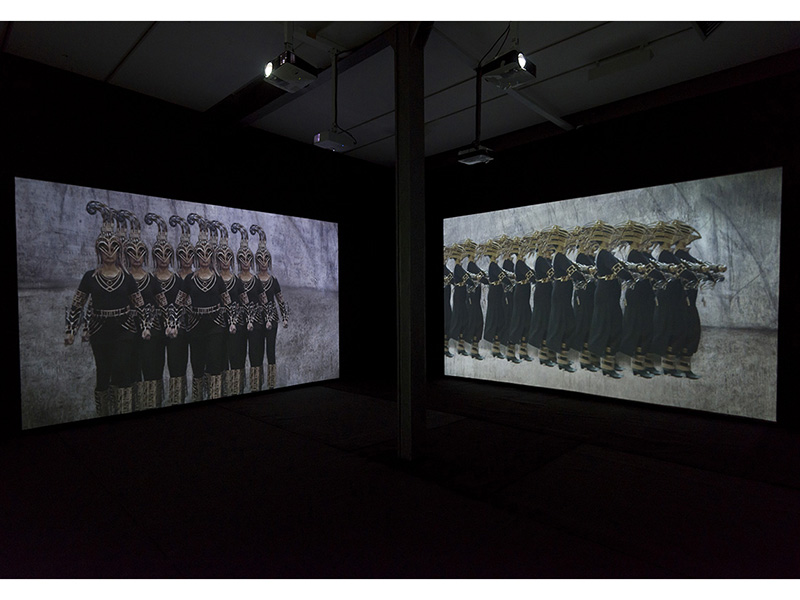

Shakuntala Kulkarni is a contemporary artist living in Bombay. Two of her fascinating works, Of Bodies, Armour and Cages, shown at the India pavilion at the Venice Biennale, and, more recently, Juloos and Other Stories, are both an appropriate mention in this context. Both projects are dynamic and multidisciplinary body of works. Of Bodies, Armour and Cages consists of cane armor, and is a set of wearable sculptures comprising 11 “costumes” and eight examples of headgear, supplemented by a suite of performance photographs showing the artist wearing these elements in various private and public situations. The work is essentially a response to the escalating violence against the female body in public and private spaces. The armor, on one hand, adorns and protects the body, and on the other, restricts it, trapping the self and becoming a cage. The work seems to mock this notion of protection for the female body.

Juloos and Other Stories consists of videos, drawings, prints, and cane objects that include necklaces and rings. In the videos, the artist, costumed in elaborate cane armor, assumes the persona of a Zen warrior. In the words of the contemporary art critic, cultural theorist, and independent curator Ranjit Hoskote, “If the nurturer is going to be rendered vulnerable, defenceless, conspired against by the brutish patriarchal assumptions and public behaviour of a society that increasingly displays the worst combination of a feudal past and an anomic present, you know what you have to do. You choose the way of the warrior… For this procession of selves, armour becomes a second and necessary skin and ornament must play a lethal role.”[2]

The display of objects is modeled after a jeweler’s store: The works, set on pedestal cases suggestive of vitrines, confuse the viewer by subtly playing up and drawing attention to the concealed commodity nature of artwork. Another very interesting dimension to the projects is Kulkarni’s collaboration with three cane artisans for making, experimenting, and improvising the constructions, and the mutual education and cross-pollination of ideas that ensued among them as a result of their interactions. Under Kulkarni’s direction, this informal group gradually stepped beyond the commodity approach to respond creatively to the artist’s design problems. Kulkarni, too, gained fresh insight into material vocabulary through this cooperation.

In my view, the works mentioned above set great precedents for the kind of individual and collective investigation that could be the basis for an authentic field of Indian contemporary jewelry.

The Emergence of Indian Contemporary Jewelry

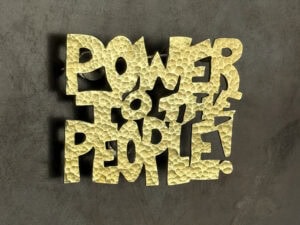

A new generation of jewelry artists has been slowly emerging. Another artist who seems to have toyed with military vernacular to express female power is Shilpa Chavan, or Little Shilpa, a Bombay- and London-based milliner who works across fashion, styling, and art. In Battle Royale, a series from 2009, she uses vintage royalty and military paraphernalia to create a range of headgear as part of an effective overall stylization. Another set of works that I find immediately striking is the brocade and Plexiglas necklaces that break the class code. Silk brocade has long been the fabric of luxury and nobility. In Chavan’s interpretation of a contemporary neo-modern Bombay bazaar, the use of acrylic layered over the brocade cutouts takes things into a more democratic dimension, reminiscent of the Indian streets of today where it’s not hard to see these two worlds, traditional and modern, coexist.

Sham Patwardhan Joshi is an Indian jeweler living in Germany. Trained under Professor Georg Dobler, Joshi has been working on developing his own unique language. Following the studio jewelry model and a process-driven approach, Joshi is a prolific maker, spending hours at the workbench. His Thinking Hands necklace, consisting of numerous tiny sculptures of gesturing hands shaping and reshaping themselves, was shown at Schmuck, in Munich, in 2016.

Pallavi Verma is a contemporary jeweler trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp and now based in Bangalore. Verma’s work clearly expresses transcultural experiences. Jewelry, for her, is more than just mere ornamentation. It’s about hidden revelations, marking boundaries, emotions, and identity. She makes playfully intimate and interactive pieces such as The World Behind You brooch, modeled on a rear view mirror, or body switches turning the body on/off. She tries to involve or touch the wearer and the observer physically and psychologically with her work.

Masooma Syed is a Pakistani artist who has lived between Delhi and Lahore. Syed works with assemblage, making miniature wearable sculptures that take jewelry beyond commodity into a conceptual realm. She considers the body an intimate canvas for her self-reflexive open-ended works. Combining silver, copper, and bronze with human nails, whiskey bottle caps, old perfume bottles, and paper, she constructs restless narratives that challenge material hierarchies, conventions of beauty, and dichotomies of permanence and ephemerality.

Masooma Syed, Your Majesty, necklace, human nails, nail enamel, cord, photo courtesy of the artist

Smriti Dixit, a Bombay-based artist who makes large-scale material-based installations, created a series of complex and spontaneous fabric art jewelry for a 2015 show she called Re-doing/Undoing. Questioning distinctions between art, craft, and design was one of the motivations behind the work. The beautiful pieces, which bore the mark of the artist’s hand and process, were later showcased at Lakme India Fashion Week.

Material Immaterial is a Bombay-based design studio following a purist, minimalist approach. Their series called Chimera is a set of brooches and necklaces in concrete and brass, inspired by Escher-esque illusions.

Adesh Tolumbia, a recent graduate of Sheffield Hallam University, UK, in search of new materials, has been making jewelry with pomegranate skin.

Adesh Tolumbia, Alokik, 2019, necklace, pomegranate skin, silver, enamel paint, 75 x 70 x 20 mm, photo courtesy of the artist

A 2013 collaboration between Manish Arora, an acclaimed Indian fashion designer, and Amrapali Jewels broke new ground with an Indo pop and punk range inspired by the decadence of Indian jewelry and antique and tribal pieces in the Amrapali archive. Many Indian fashion designers have since been experimenting with jewelry.

Over the last few years, several online and offline stores specializing in Indian contemporary jewelry have provided some impetus in bringing attention to jewelry as a stand-alone discipline, with its own identity away from fashion and textiles, and in promoting nonprecious materials. At one such store, Nimai, one can see jewelry from glass, ceramic, wood, paper, found materials, and so on. The platform aims to “celebrate contemporary jewelry artists of India.” The most conspicuous development has been the recent emergence of modernist minimalist forms, following international trends. Lakme Fashion Week (one of the premier platforms for fashion in the country) has recently dedicated a section to jewelry and accessories, in an attempt to bring designers making those items to the forefront and encourage specialized industries.

The Indian Craftsman

The dilemmas and legacies of craft in post-Independence India remain a contested domain. For many, the figure of the Indian craftsman captures the essence of India itself. On one hand, she’s seen as a symbol of national identity that needs survival and revival, held up as an ancient repository of hereditary skills, the key to an indigenous social and political economy; but on the other, she’s considered a sign of economic underdevelopment, a symptom of capitalist exploitation, and a symbol of the damage to preindustrial society by the forces of modernization in India. Designers are seen as a vehicle to keep the traditional crafts alive by bringing them in a modern context with fresh designs, thereby creating new demand in the rising domestic design industry, and a source of income for the craftsmen.

The traditional division of labor between creativity and production, which speaks of old class and caste differences, remains the norm. Designers are opting to get their designs made instead of making themselves to keep costs low and productivity high, allowing for the possibility of catering to a demanding market, ultimately remaining market driven.This is characteristic of Indian society at large, which is notorious for being a “do-it-for-me” culture. All physical work, such as woodworking, painting, or household maintenance like plumbing, gardening, cleaning, etc., is strictly the arena of servants and the unskilled workforce. Recently, the concepts of DIY and maker fairs have been taking root and are a welcome departure from this, encouraging community interactions and a democratic, collaborative, and organic development of ideas. It’s important to challenge how the role of the craftsman is assumed in an Indian setting and look at collaborative supply chain models in lieu of the traditional ones. The example of Kulkarni’s working methodology with the cane artisans is a great example of how this could be done. Jewelry education and institutional support are other aspects where change is needed. India has much to offer to the field of contemporary jewelry, and these exciting new developments are great small steps in this direction.

Resources

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ldQbqPcOgtA&t=1157s (accessed on July 20, 2019).

[2] http://shakuntalakulkarni.com/juloos.html.