This year, the 17th Erfurter Schmucksymposium took place August 5–19, 2019, in Erfurt, Germany. It had the motto—and how could it be any different on the centennial of the most important design school of the 20th century?—”100 years of Bauhaus.” And thus the title 17:100 does not stand for the final score of some unknown sport, but for the age ratio of Erfurter Schmucksymposium to Bauhaus, expressed in digits. But it’s much more than a numerical relationship. It’s an expression of an imaginary relationship. And there were as many relationships as there were participants.

RELATED: Sarah Thornton’s Lecture at AJF’s 2018 Collectors Symposium

RELATED: Jemposium, in New Zealand

RELATED: The Gray Area Symposium

This is the only meeting of jewelry artists that, in addition to the theoretical part, focuses on working together for 14 days. Almost the entire elite of international jewelry design has already participated in the Erfurter Schmucksymposium in the past, among them Ruudt Peters (The Netherlands), Anton Cepka (Czech Republic), Bernhard Schobinger (Switzerland), Peter Skubic (Austria), Karl Fritsch (Germany), Helen Britton (Australia and Germany), Marc Monzó (Spain), Attai Chen (Israel), Suska Mackert (Germany), Carla Riccoboni (Italy), Karol Weisslechner (Slovak Republic) Brigitte Moser (Switzerland), Benjamin Lignel (France), and Masako Hamaguchi (Japan).

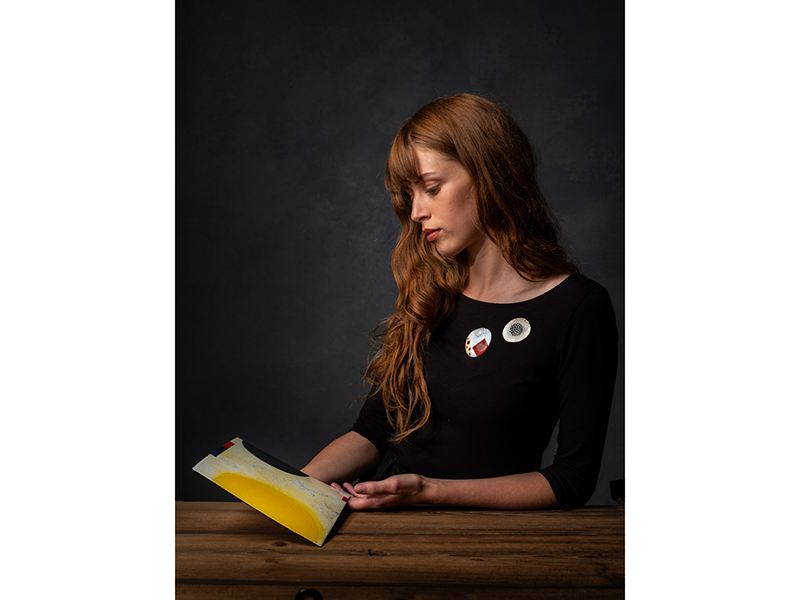

As on every occasion, 10 participants took part in this year’s symposium:

Mandy Rasch (Germany) has joined in the symposium several times. Born in Thuringia, she not only works as a jewelry artist, but also took the baton of the founding generation with Karola Torkos and occasionally Felix Linder (who also participated this year, and whose explorations are described below), and is one of the organizers of the event. Her profession is industrial enameling, with which she transforms such unusual objects as jerrycans or kitchen sieves into artistic objects. The technical possibilities available at the symposium (a large enameling furnace, injection chamber, etc.) have been discovered by other hobbyists.

Katharina Kielmann (Austria/Germany) brought Bauhaus weaving and the baking arts, for which the Thuringians are well known, and enameled patterns reminiscent of carpets produced by Gunta Stölzel, Anni Albers, or Margaretha “Grete” Reichardt, and of baking sheets.

Ketli Tiitsar (Estonia) also experimented with the material enamel and the technique of enameling. In addition to a series of objects from short, bundled pieces of wood, which she partially colored after confrontation with the various color teachings of Bauhauslers, she experimented for study purposes with enamel on small iron bodies.

Sophie Hanagarth (Switzerland), who lives in France, plays with the symbolic power of the hand of Fatima (or the hand of Miriam) and still retains an analytical look. Her interpretation of this symbol produced amulets that were enameled, nailed, or chased, or whose shapes quoted the Gothic windows of the Erfurt Cathedral, or the Bauhaus tricolors in blue-red-yellow.

The ceramist Anat Shiftan (US) had two reasons to come to Erfurt: First, an invitation to the Erfurter Schmucksymposium, and, second, she wanted to look for traces of her family—her grandfather was a rabbi in Erfurt, and her father was born in this city. She develops enamel on the basis of extensive color examinations, which ultimately took formal reference from textile designs by Bauhaus women.

Jamie Bennett (US) was one of the American trailblazers in the reinterpretation of both the material enamel and the technology of enamel in the 1980s. In addition to making his masterfully produced small silver slices, during this year’s symposium he dedicated a painterly work to Wassily Kandinsky, who worked at the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau from 1922–1933.

Melanie Isverding (Germany) has resorted to a material that isn’t necessarily typical: cotton yarn. In Erfurt, with silver-blackened frames and black yarn as a starting point, she created a pendant with very subtle ornamentation.

A new interpretation of the muff was created by Sarah Schuschkleb (Germany). It was based on the stereometric costume designs that Oskar Schlemmer had developed for his ballet stagings, which allowed the dancers only a limited, almost robotic movement. The inside of the black muffs made of plastic also determines the movement of the wearer. Working with found materials has become in recent years a popular method not only in the visual arts, but there are also interesting examples in the field of jewelry.

Felix Lindner and Karola Torkos (both Germany) also use found objects. Lindner transformed an oyster shell into a container for salt, with the silver ball feet of this vessel reminiscent in their color and form of the beautiful gray pearls that could have grown in the oyster. Committed to building, Torkos used plastic building blocks to create a series of bangles that are somewhat similar to the Bauhaus architects’ cubic architectural designs, and from the play with the colors of the building blocks, a necklace and earrings were created, from which a series could later be developed.

There were the direct references, the most obvious being the tricolors yellow, red, and blue, and then there was the confrontation with the Bauhaus masters, their biographies, theoretical considerations, pedagogical teaching approaches, their works, including their formal and color language, but also the institution itself as a place of common creative activity, working and living in the community. And sometimes it was the critical mental reflection of what has remained of the Bauhaus, what is made of it, and what could ultimately endure. Playful or serious, obvious or rather subtle, or in denial, the confrontation with the Bauhaus is reflected in the works that arose from the 14 days of the symposium. In addition to finished work, work samples, sketches, documentation of processes, and technical innovation, the 10 artists developed new materials as well as interdisciplinary expansions of their own fields of work.

The Bauhaus and its ideas were met in very different ways in the jewelry that was created in Erfurt this summer. At the end of every symposium, the results are presented as part of an exhibition. In the past, these presentations have taken place at the Kunsthalle Erfurt, Galerie Waidspeicher, and the ruins of the Barfüsserkirche (which the Bauhaus master Lyonel Feininger painted). This time it was at the Angermuseum Erfurt. This—the museum where in the 1920s the Bauhaus artists from nearby Weimar presented their works, gave lectures, and so forth, and where Feininger had a small studio during his stay in Erfurt—was the perfect venue to display the work created during the symposium held in the year of the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus.

Erfurt, the capital of Thuringia—a city of 200,000 inhabitants—is located in the “green heart” of Germany. With its many medieval streets and alleys and a pleasant atmosphere, it’s a first-class tourist magnet. Erfurt has many attractions: it boasts the only bridge north of the Alps lined with shops, the Krämerbrücke (translation: the shopkeeper’s bridge); Meister Eckhart (born 1260, near Erfurt, died 1328, Avignon, France) worked in this city; and Martin Luther studied theology at the old university and was ordained a priest in 1507 in the Augustinian monastery of Erfurt, where there’s also a precious painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Additional works by the Cranach dynasty are housed in the Angermuseum Erfurt, which also features a small but exclusive collection of international contemporary jewelry.

Despite the fact that Erfurt has never been a place for the creation of jewelry in the classical sense, there are two extremely notable apparitions in jewelry: On the one hand, the “Erfurt Schatz,” which consists of more than 700 Gothic pieces of jewelry—among them a traditional Jewish wedding ring, which served as a ceremonial object—silver coins, and numerous silver bars. With a total weight of 30 kilograms, it’s a real treasure. This valuable find was excavated in 1998 near the famous Krämerbrücke. Today, the objects from the end of the 13th century and the first third of the 14th century are presented in the Alte Synagoge (Old Synagogue), just a few steps away from the Krämerbrücke.

And the other noteworthy event: In 1984, something happened that Erfurt has inscribed in design history. Uta Feiler, Rolf Lindner, and Helmut Senf, three young designers who returned to Erfurt after their studies, launched the Erfurter Schmucksymposium. (Later, Bernhard Früh joined the group.)

This symposium was intended to broaden the circle of interested, innovative jewelry designers; to become a melting pot for creative thinking and working; and to provide a foundation for important networking. Until the sixth edition, the symposium took place at the private studios of the three founding goldsmiths, which were all close to each other. Every other year, invitations were sent—in the beginning to jewelry designers from the German Democratic Republic; from 1990 (since the fourth symposium), also to colleagues from Western Germany; since the fifth symposium, international artists and designers have participated. The organizer of the symposium is the Verband Bildender Künstler Thüringen e. V. (Association of Fine Artists in Thuringia). Today, this phenomenon has found its way into the relevant design literature.