Late in December 2019, I began hearing small rumblings and snippets about a mysterious virus (now known as SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19) spreading across the world. At the time, this new illness had little immediate bearing on my life until mass shutdowns across the globe began taking place. Within a couple of weeks, I, like many others, began to think about the implications that shutdowns would have on the world.

Since the start of 2020, we’ve seen various degrees of what shutdowns look like on a mass scale within and beyond the arts world. Within our field, we’ve witnessed exhibitions, community arts, and educational systems shift from standard business to unprecedented modes of cancellations, suspensions, problem solving, and remote access. News of events like Schmuck being canceled and graduate thesis exhibitions being displayed strictly online became the new normal. In recent weeks, programs and institutions have shut down permanently from financial strains and deficits that were already present, but further exacerbated by the pandemic.

While a collective gut reaction of panic and confusion replaced routine—mostly due to lack of information and understanding of COVID-19—I noticed a perseverance within creative circles gain momentum. In my own network, a passionate dialogue on how educational institutions can adapt to COVID’s challenges has moved me. Facebook groups like “How the hell do we do this? Teaching Visual Art Online” became an unusual, humorous, but also seriously necessary and collaborative resource for arts educators trying to navigate the new educational landscape.

With a new school year approaching, and the sanctity of our educational systems at the forefront of most students’, parents’, politicians’, and educators’ minds, this article aims to bring perspective to the ongoing responses to the pandemic from the angle of the educator. It features portions of interviews from various jewelry and metalsmithing faculty from across the globe, examining the unique and diverse approaches to modifying curriculum, in addition to the unexpected or rarely addressed problems such as social equity and accessibility within the jewelry/metals educational field that COVID-19 intensified. The participants included:

- Leslie Boyd (Denver, CO, US), Assistant Professor of Art, Jewelry + Metalsmithing Area Coordinator, Metropolitan State University of Denver (MSU Denver)

- Sungyeoul Lee (Seoul, Korea), Assistant Professor, College of Design at Kookmin University

- Jorge Manilla (Ghent, Belgium), Head Professor Metal and Art Jewelry, Oslo National Academy of the Arts

- Lisa McGovern (Glasgow, Scotland), Curriculum Head of Craft & Design, City of Glasgow College

- Kerianne Quick (San Diego, CA, US), Assistant Professor of Art, San Diego State University (SDSU)

- Jess Tolbert (El Paso, TX, US), Assistant Professor of Art, Head of Jewelry + Metals, University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP)

- Jennifer Wells (Certaldo, Italy), Adjunct Faculty, Santa Reparata International School of Art, Florence

Melis Agabigum: When and how did you shift your approach to teaching studio-based courses to teaching through a mediated format during the 2019–2020 academic year? What format did your instruction take?

Leslie Boyd: We moved online rather suddenly in March. Our school uses Microsoft programs such as SharePoint and teams, which were primarily utilized for instruction. For my classes that met twice weekly pre-COVID, I moved to a once-a-week synchronous group meeting, which I recorded for those who couldn’t make it. I met individually with students as needed during the other course time. My school is an open enrollment commuter institution. Many students didn’t have the proper tech or internet, or had family care and work obligations that made regular mandatory synchronous meetings impractical and inequitable, so if needed/mandated, all course work could be completed in an asynchronous manner.

Sungyeoul Lee: When COVID-19 broke out, most universities in Korea were about to start the new semester. Schools postponed the first classes for two weeks and, in the meantime, we focused on the program training for all professors, such as Zoom, and expanded and updated the existing online course platform capacity.

Most of the training was done online, but offline training for a small number of people took place several times as well. Through this training, conducted by experts, many professors were able to learn how to produce online lecture video and to deliver it to students effectively. Based on this training, we produced and updated videos of studio-based courses every week on the online campus platform, and were able to guide students on basic skills. As a result, we were able to successfully cope with the online lectures [which we began conducting] two weeks later without chaos.

Jorge Manilla: The first format that the institution took was to use digital Zoom media. It was implemented as a platform for all staff and students. My format changes were divided in two parts. The first one (sent to all the students) consisted of some assignments designed and created for the profile and level of the groups of students we have. The second part was the Zoom meetings with students. The first meetings became a forum to listen to their feelings, thoughts, and frustrations. Based on that, I continued making decisions for the weeks that followed.

Lisa McGovern: We closed our campus on March 17, and immediately switched to remote learning. We already have in place an E-Portal for students to access teaching material online, so they had immediate access to information they needed in order to continue. We took the rest of the week to get organized and then proceeded to teach remotely. We set up private Facebook groups for each cohort and started a mixture of video demonstrations and online chats and discussions. We did this until the decision was made about how the curriculum year was to proceed. Students then had the option whether they wanted to continue or receive a predicted grade for their final project.

Kerianne Quick and Jess Tolbert: For the both of us, the shift to teaching remotely happened mid-late March. Actually, we were both in Munich, Germany, attending the significantly reduced Munich Jewelry Week when everything began to rapidly change. After we arrived back to the US, both our institutions gave a week to adjust to the online format for our studio-based courses—a single week!

The two of us have always wanted to do a cross-border collaborative project with our students, and while discussing how we’d go about our courses we decided to work together to create a series of projects for the students at UTEP and SDSU.

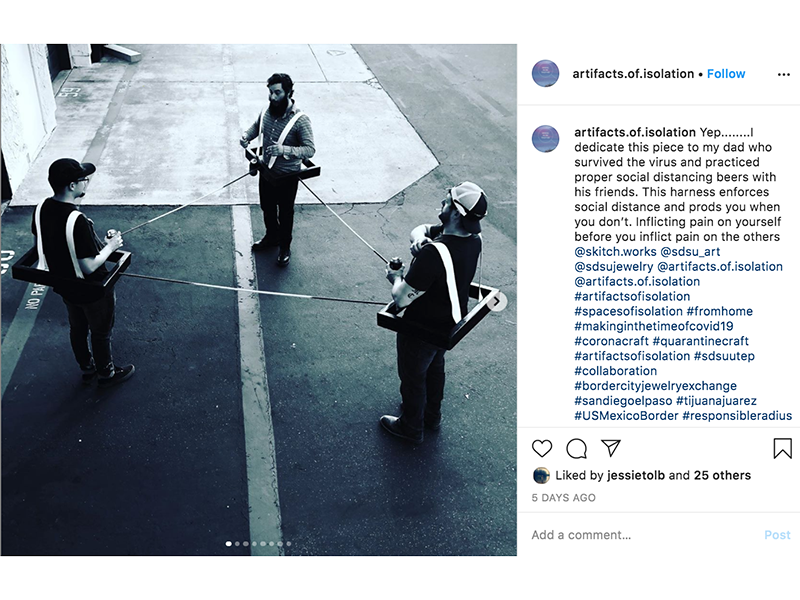

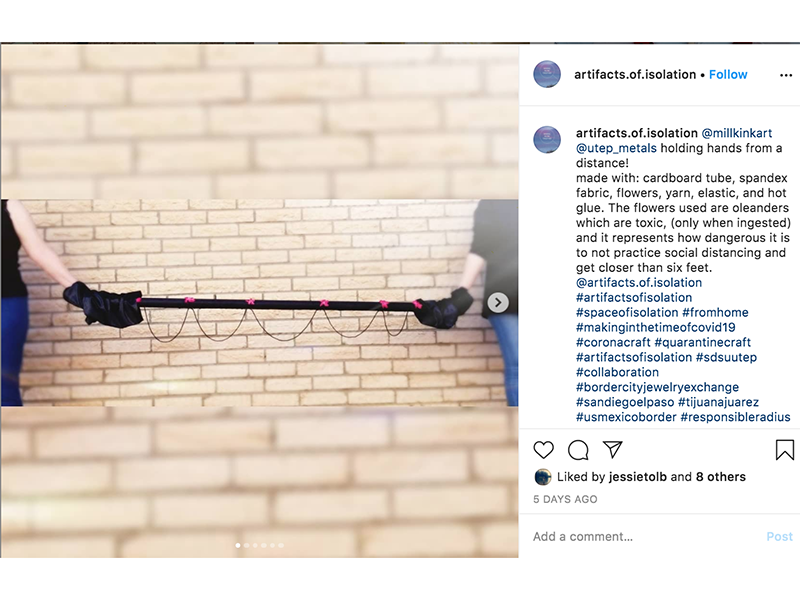

Courses taught via Zoom took the form of material exploration, creating work inspired by the different spaces in and around the students’ homes, and a large-scale “responsible radius” wearable that highlighted our new social distancing standard of six feet. In order to develop a sense of community and collaboration in this time, we created a shared Instagram account[1] for the students to upload their work every week. We also found ways for them to give one another feedback and critique using Google Drive docs. Being able to offer advice and then see final results through these two online platforms allowed the students to get to know each other a bit better and build connections.

Jennifer Wells: I teach for a study-abroad program based in Italy. We were informed that students would be leaving and returning to the US at the end of February. My class was on a Tuesday/Thursday schedule. On Tuesday, I had one student who was being required by her home institute to return home, and by Friday everyone was being forced to return to the US. In some cases, students had only 48 hours from notification (that their home institute was requiring their return) to boarding a plane home.

The school spent the next week transferring all classes online, and offering assistance to make demonstration videos. A week later, Italy went into a lockdown and we were not allowed to travel or leave our homes except for grocery shopping or doctor visits, so all information had to be produced from home. I set up my kitchen table with the most basic tools that most people have at home, i.e., hammer, block of wood, glue, string, paper, sticks, and of course pasta. Instruction came in the form of handouts with photos of step-by-step processes and PowerPoints giving examples of alternative material jewelry pieces. I kept in touch with students via e-mail and they uploaded their final at-home projects to GoogleDrive.

Finding a balance in time allocation is a difficult undertaking in the best of circumstances. How have you navigated “time” in living, teaching, and making in recent months?

Jorge Manilla: I live between two countries, which makes everything more complex. Fortunately, I was able to stay in Belgium, where I have all the facilities to work, and where I also have my home. On the other hand, distance always makes everything more complex, but I was very aware of the complexity of the situation and decided to use technology in an efficient way to shorten times in my contact with the students to answer questions and be present when necessary.

This situation allowed me to create more content for the students, and prepare good teaching materials at different levels. I was also able to combine my own artistic practice, and this gave interesting results with what I shared with the students. This time also allowed new perspectives to open in the way of seeing teaching and what we believe was correct. I believe that this pandemic has helped open possibilities to rethink teaching systems around the globe.

Jennifer Wells: Being at home, and not allowed to go out for two months, allowed/ required that I set a daily routine. I break up my day into blocks dedicated to the different aspects of my life and work.

Are you part of any teaching resources or groups that have supplemented your transition to remote learning?

Lisa McGovern: I’m not part of any formal group; however I’ve been accessing online forums and discussions of teaching groups that share resources and have an open platform.

Kerianne Quick and Jess Tolbert: In the beginning a few groups were formed on Facebook that were helpful in understanding how everyone was adjusting to the challenge—“Online Art & Design Studio Instruction in the Age of ‘Social Distancing,’” and “College Jewelry Educators Remote Teaching Forum.” We also initiated an “artist talk” shared Dropbox where educators, artists, and curators generously shared a short recorded artist talk, in trade for access to the rest of the talks in the shared folder. The generosity of the field certainly made a difference in problem-solving some of these new challenges quickly.

Jennifer Wells: I follow several Facebook groups that were created a few weeks after SRISA had already shifted online. They’ve been helpful resources for information and materials that I will use in the future. For specific projects, I connected with colleagues directly and found that to be a great, open exchange.

Leslie, would you elaborate a bit more on establishing the Facebook group “College Jewelry Educators Remote Teaching Forum”? Have you had any feedback about the impact that this group has had on educators? How do you see this collaborative mode of teaching evolving?

Leslie Boyd: This group was formed from need, first and foremost. Mallory Weston and Emily Cobb are two of my closest friends and are fellow educators. As the shift to remote teaching was taking place across the country, we were constantly communicating with one another through text and email, sharing resources we had found. Mallory Weston created a shared Google Drive folder to try to consolidate some of these resources after a post in Critical Craft Forum found many others eager to join the conversation.

Critical Craft Forum and some of the other Facebook groups related to remote studio teaching continued to be invaluable, but one would have to wade through them for jewelry-specific resources. It seemed that the logical next step would be to create a closed group in which to specifically continue these conversations. The response to the group has been fantastic! Lots of educators added resources to the Drive folder, shared recorded lectures, and project prompts were shared and collectively built upon. People seem appreciative for the community that has been built. It has been great to connect with educators from across the country. In some ways it’s what I’ve always longed for during the SNAG conference educator panels!

As we move away from the spring semester and begin building out curriculum for the fall, it seems that much of the country’s college campuses will still be in some form of lockdown/social distancing, and the conversations are continuing. We’ve stepped away from the triage situation that this group once filled into creating sustainable curriculum for the very different economic, cultural, and social landscape we now live in.

My institution announced our reopening plan for the fall. Most courses across the university will go online. The art department has one of the largest number of courses that will have some in-person time. Social distancing caps dictate a reduced number of students in the classroom at any given time, requiring staggered instruction.

Many students don’t have access to traditional jewelry studio equipment. How did you adapt your teaching or projects in response to this, for technical-based learning?

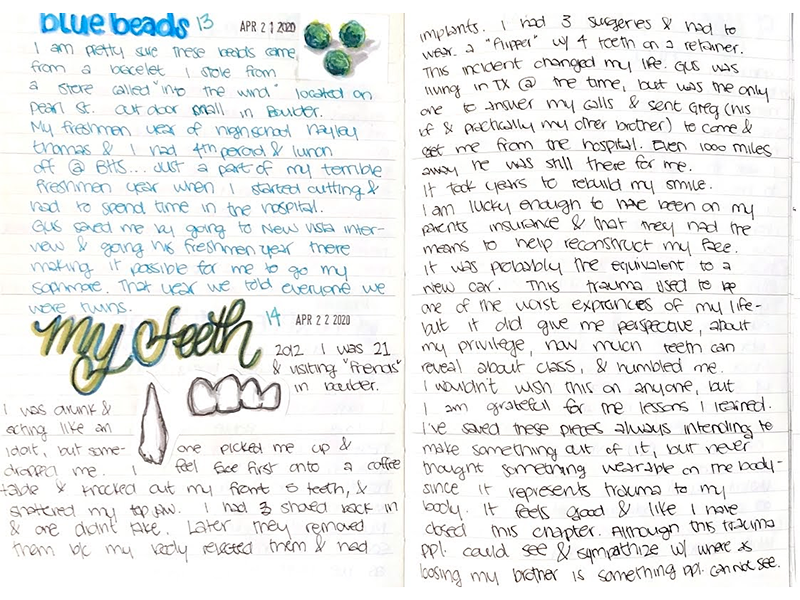

Leslie Boyd: We were moved off campus very suddenly so I didn’t have time to create expanded tool kits for student use. The only jewelry course I was teaching in Spring 2020 was an intermediate course. After conducting a survey[2] to assess what equipment, access, and concerns student had after shifting online, and with a keen eye to creating an equitable and accessible space, I developed a multipronged approach to how students could finish out the semester.

We were already midway through a project where we were assessing and subverting the concept of value. This couldn’t have been a better fit for suddenly being without the tools, equipment, and resources usually utilized in the field. I met individually with students to pivot as needed so that the projects could be further developed and completed with the limitations they faced.

For the last project of the semester, students could choose from one of four paths: build your own artist residency, where they had to write a proposal for a project they would complete with their available resources for the final weeks of the semester; design your own limited production jewelry collection, where students researched, storyboarded, and designed a small collection and brand identity; the “tell me what to do approach,” where they were given a weekly mini project—think Project Runway or The Art Assignment series by PBS (no one chose this); an archive based on Renée Zettle-Sterling’s “In Liminality” project,[3] where they had to document their days, create an object, or study each day, and develop a way to catalogue that work.

Sungyeoul Lee: Ten weeks into the semester, we planned to be allowed partial access to the studio, so we had to conduct about 10 weeks of online classes. The class started with PowerPoint files produced with related books and reference videos, focusing on the essential knowledge of metalsmithing techniques and theory that students should learn within the semester. Afterward, classes were organized by presenting research, sketches, and modeling prepared by students in relation to project production, and I gave them feedback so they could correct the design or direction of the project. Sometimes I gave them some time to draw the idea sketch while we were in the online class and they shared what they drew with students online.

The actual production of all the projects was postponed until 10 weeks later, and the preparation process, such as research and idea sketches for the projects, were carried out first. Materials and equipment that could possibly be at home, or the nearby Makers Lab, were used for modeling, and many students participated in the class by producing life-scale modeling with not only modeling clay and modeling foam but also 3D printing technology. We usually carry out two to three projects in one semester. The number of projects was not reduced, but the level of difficulty was adjusted to allow students to produce the project in a shorter period of time. For example, an anticlastic project in which students have to build a basic anticlastic bracelet shell structure without building the hollow structure since they already know how to solder. They’re currently working with real material for the project during a six-week intensive practical period left until the end of the semester.

Jorge Manilla: It was very important, as head professor, to be aware of the situation and look for solutions for the first weeks of the restrictions of this pandemic, and then find later solutions for the first months. This made the technical teaching become more theoretical through Zoom meetings, through documents as technical sheets that I made to share with the students. We then moved the theoretical technical solutions into material manifestations with various forms of joining, creating lines of ensembles, and nontraditional material explorations based on the tasks I gave them.

These tasks were supported with a list of links to videos from different platforms where artists talk about their work, [as well as videos from] philosophers, critical scientists, and gallery owners.

My main intention was to make the students move their creative process from a very practical and material position to a more theoretical and critical side, and then return to the material with a different vision and improve the use of other materials and the methodologies they were using so far.

Lisa McGovern: One of the projects was design-only, so adapting this was slightly easier. We started to break the brief down into more manageable chunks and uploaded easy-to-follow templates to assist with the process. The other projects used alternative materials and the design was to be inspired by a poem written by students in the Professional Writing course. We encouraged students to continue, without the necessity to include more precious metals. We encouraged them to use found objects and resources available in their homes.

Unfortunately, the final-year students had just started their last project, which specifically included manufacturing. We made the decision not to continue with this and give a predicted grade. It would not be a level playing field to grade them on, and some staff had limited workshops at home to teach.

Kerianne Quick and Jess Tolbert: We both operated under the assumption that students do not have access to the tools needed to complete traditional metalsmithing projects. While some might have a few things here and there, it would not be fair to assign work anyone would be at a disadvantage to complete, whether that be because they don’t have the equipment, can’t afford the equipment, or because many of the things we do in jewelry studios wouldn’t be safe at home without proper instruction and understanding.

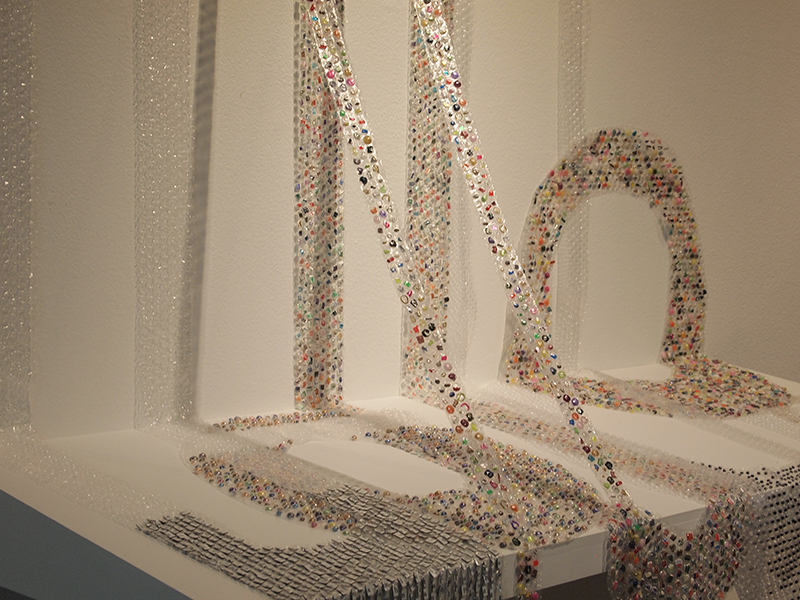

The technical component of remote learning came in the form of alternative materials. We didn’t assume students had access to any particular material, nor did we feel comfortable asking them to go out shopping to procure material. Therefore students worked with whatever materials they had at hand—any and every thing became material for making. We challenged the students to creatively problem-solve and think differently about the things and materials around them, while also highlighting the historical and contemporary use of “alternative material” seen in the field of art jewelry.

We emphasized the importance of material to speak about time and place, and encouraged them to consider the way material provides meaning and context to the work they do. To facilitate teaching we made a series of “how to” videos showing a variety of techniques that were likely to be available to the students, such as embroidery and knotting, making a homemade pin vice for drilling, using office supply equipment such as hole punches for plastics, or staples for making functional or aesthetic connections. It was important that these be recorded videos rather than live video demonstrations. One of the challenges of the shift to online was that students left our respective regions. Forced from their dorms or other local living situations, the students were in a variety of time zones, experiencing high levels of stress and serious competing priorities. The videos allowed the students to watch the demos on their own time, and apply the info to complete the projects

What has been the greatest challenge for you during this time?

Leslie Boyd: I already take on a lot of emotional labor as an educator, and this last semester amplified that in ways I didn’t think possible. Students were facing illness, family care needs, homelessness, food insecurity, lack of tech/tools/space to work, were needing to work more hours to counterbalance for family members who had lost jobs, etc. Making sure that they still had a meaningful semester, were emotionally supported, had access to the resources they needed, and had enough flexibility to work into their new lifestyle was extremely difficult. No one student’s needs were the same.

For the senior thesis students, the loss of an in-person exhibition—the event that their entire education has been working toward—was extremely difficult to manage. Keeping their morale up and having them engaged to keep moving forward was emotionally draining.

Sungyeoul Lee: Above all, the biggest challenge was how to improve a student’s concentration in online classes. As classes are conducted online, most students take classes at home, and they often lose their concentration because they’re too comfortable, or they’re easily distracted by various surrounding factors.

To prevent this, surprise quizzes, individual presentations, and small group activities were frequently given during the class and at the end of the class to check whether students were paying more attention during online classes so that students could concentrate more on the classes.

Lisa McGovern: Keeping students engaged and keeping your own sanity. We’ve tried to find ways of engaging with all students, but different sets of circumstances made this not possible. Trying to maintain standards of teaching was another challenge, as not having access to materials and equipment to do demonstrations of techniques made it trickier to teach, so we adapted and simplified our methods.

Have there been any positive teaching moments that you were surprised by during your COVID curriculum? Describe the instance and outcome.

Jorge Manilla: In general, I believe that difficult or complex situations are a learning process, and from the beginning I took this pandemic very seriously and tried to be as positive as possible in finding solutions and creating possibilities in the face of limitations. This pandemic helped me to find solutions little by little depending on the needs of the students and the changes that were happening. Obviously, there were difficult times, but it was very satisfying to feel that I could solve them.

The feeling of knowing myself locked up and with limitations helped me to rethink my personal work, my work as an educator, to find time to do everything that I hadn’t been able to do due to time constraints. Today I can look back and say that out of worry and sadness, this experience has been quite positive for me… but I have to clarify it’s from my own very personal point of view.

Kerianne Quick and Jess Tolbert: The students’ incredible responses to the projects. Their complete resiliency to take on the challenge to work from home and make thoughtful and compelling work: their appreciation for the projects and enthusiasm to share with one another.

At the end of the semester, we held a group Zoom between our two schools and they gave us a round of applause. It was touching to know they appreciated what they had just completed. They didn’t have to do it, we would have understood if they just couldn’t. Through the remote-learning time, many students were working—still are—at “essential” businesses, many of them live at home with their parents, siblings, and extended families, many don’t have a space to call their own for art-making—yet they showed up and made an effort that shows in their work.