The private part of private art collections creates a dilemma. As collectors accumulate art, they typically store and/or present it behind closed doors, accessible only to the personal network of the collector. This is especially true for collectors of art jewelry because jewelry, as an intimate, wearable object, is often stored in the inner sanctum of a home.

RELATED: How to Catalogue Your Jewelry Collection

When a piece is in private hands, it’s out of the public’s reach and unavailable for research by students or historians, unavailable for inclusion in curatorial endeavors, and unavailable for the general public to discover. This effectively makes the work “disappear.”

“[A] collector currently sharing on the CatalogIt HUB is connected with many Native American basket weavers. The weavers appreciate the ability to view old baskets, designs, and technical details they wouldn’t have otherwise been able to see. The weavers can see their history in a tangible way and use what they learn to inform their current work as well as teach future generations about the rich and important history of basketry techniques and materials.”[1]

At Art Jewelry Forum, we know collectors are an engaged community with shared interests, an insatiable curiosity, and a drive to connect with others. Encouraging collectors to engage with others through an art-focused social media platform dedicated to sharing personal collections may be a way to bring privately held objects back into a public conversation. Social media has revolutionized our culture in every way. Why not redefine the way we think about accessibility to a private collection?

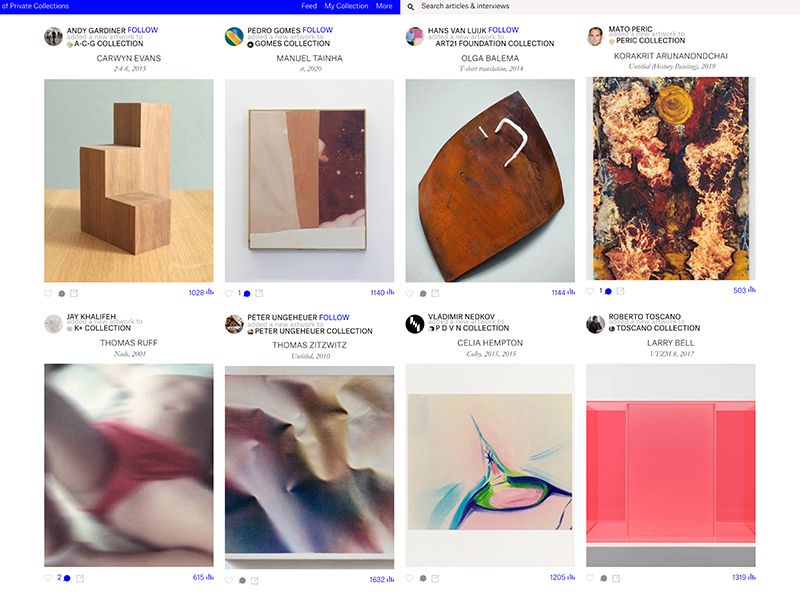

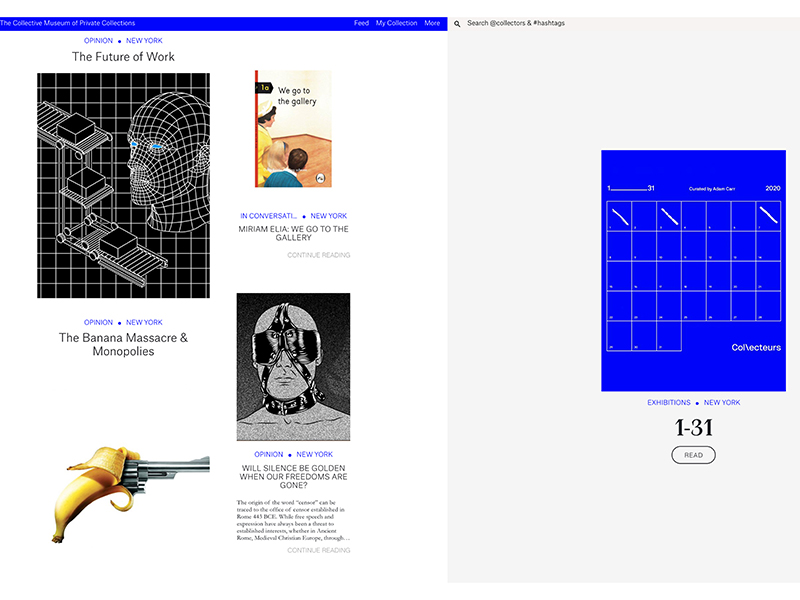

Two companies have designed exactly this type of art-focused social media platform. (Both opened their virtual doors in 2019.) Collecteur is a fine-art focused platform conceived as a cultural incubator at the New Museum, in New York, with the aim of making privately held fine art seen, shared, and discussed. CatalogIt, meanwhile, started from the recognition that privately held and small museum collections need to be seen to be studied. Both companies offer robust digital database management software to perform all the necessary functions of an arts collection management system.[2] What makes them unique from other digital collection database tools is the ability for their systems to link to a public-facing platform. Both systems give users the option to make all, some, or none of their catalogs viewable by others.

CatalogIt[3] was co-founded by Dan Rael, who has a background in the archaeology and anthropology of New Mexico, and Howard Burrows, who brought an extensive background in software development. They believe that making objects held in private collections and small museums visible to a wider audience is part of the responsibilities and joys of owning cultural art objects.

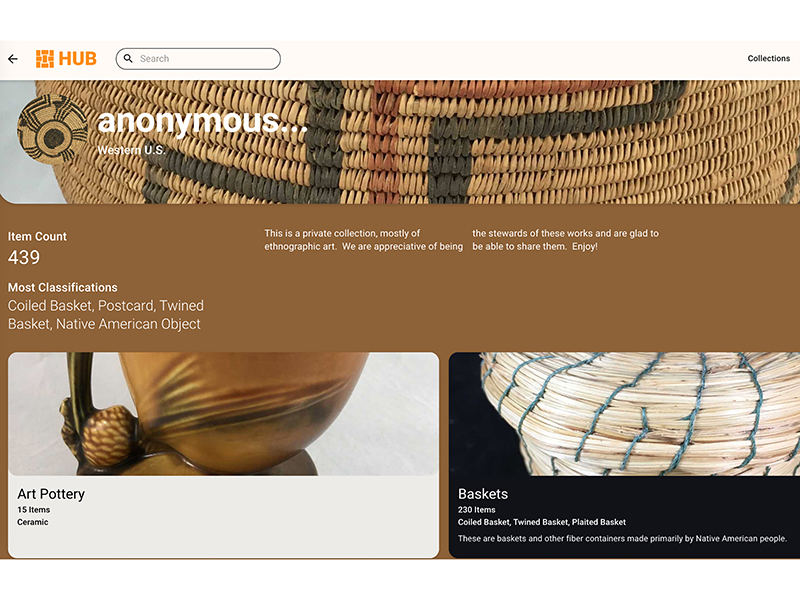

The CatalogIt software includes CatalogIt Hub,[4] a publicly accessible platform that looks and feels similar to Pinterest. The private collector creates a dedicated board with a title, location, number of images, and short description of the portions of their catalog selected to appear on the Hub homepage. By clicking into the collection, the user views the different categories that are available and can then explore the objects in a streamlined, unfussy interface.

“The ability for the public and researchers to see unique objects in a private collection that would otherwise be entirely out of reach or not available at all can be considered ‘good stewardship’ of those items. This access also allows museums and researchers to discover works that may be useful in exhibitions or scholarly publication.”[5]

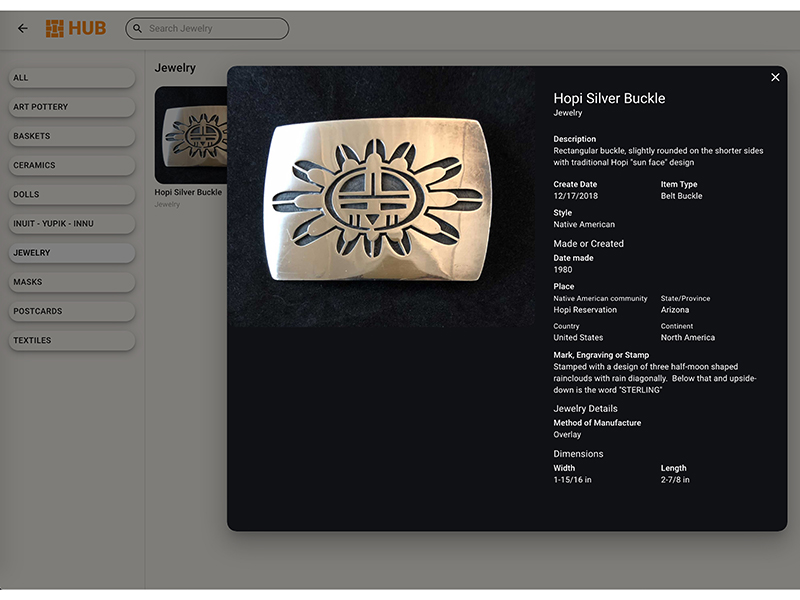

The New Mexico roots of the company are particularly clear in an anonymous collection[6] of Native American basketry and jewelry. The screenshot of the Hopi belt buckle[7] shown below gives an idea of the amount of detailed information the collector can choose to make visible, and hints at the power of the database operating behind the scenes.

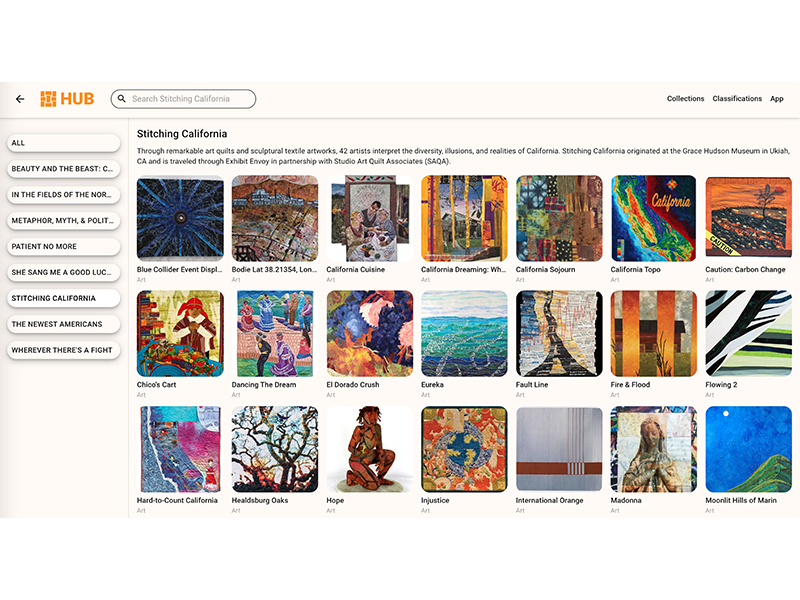

CatalogIt Hub also allows the possibility to document the details of an exhibition, either from a private collection, a small museum, or other arts nonprofit. A good example is Exhibit Envoy, a nonprofit organization that promotes California art, which uses the platform to show detailed information of exhibitions such as Stitching California,[8] a traveling textile exhibition. The viewer can see a wide variety of information about all the pieces in the exhibition, alongside a full online catalog that promotes the exhibition to new venues and shares the relevant details in a way a traditional website doesn’t allow. Now think about the temporary nature of many well-executed jewelry exhibitions, specifically within the proliferation of annual jewelry weeks. A huge amount of time, money, and labor within our field is expended for short-term visibility to an insular audience. The ability to capture details of fleeting exhibitions beyond a small-run printed catalog using these kinds of platforms is one way to help record the activity of the field by providing a vibrant interactive interface to encourage research and accessibility.

The publicly viewable data is only a portion of the data held within the CatalogIt app. Behind the scenes, the collector or organization retains private access to relevant data points such as purchase price, insurance price, insurance terms, etc. The platform provides a powerful database management tool that seamlessly translates into a pleasing, easily navigable, and uncluttered public viewing interface. The company intends to add the ability for users to communicate within the platform soon, encouraging more connection and conversations.

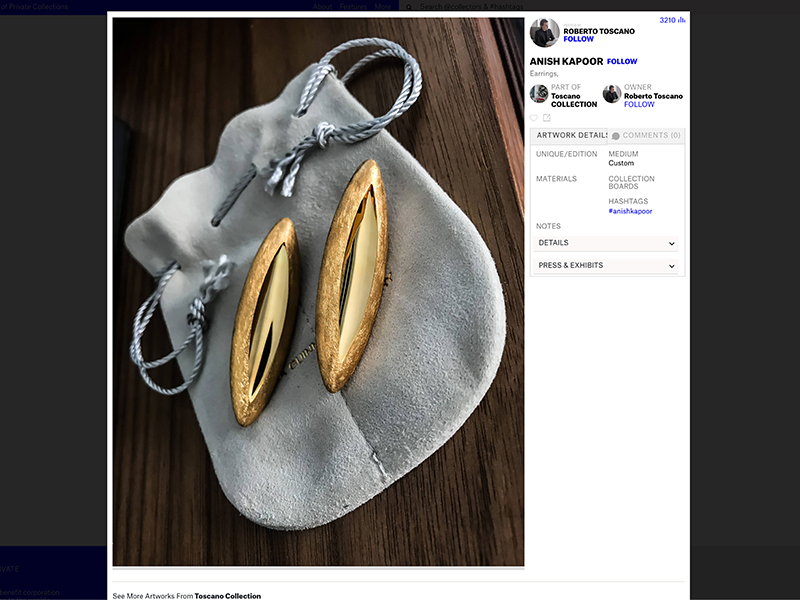

The recognition that sharing art held in private collections is in the public interests also drives the founders of Collecteur, Jessica and Evrim Oralkan. The platform’s styling is similar to Facebook, with a focus on networking, allowing users to make connections to each other by following other users of the app, as well as posting, liking, and commenting on shared content. It allows direct messaging within the app to further build connections within the Collecteur community. There are many different ways to navigate the platform. A user can choose to follow specific galleries, collectors, collections, and artists[9]—for example Anish Kapour. In doing so, the user would see all objects in the Collecteur community by Anish Kapour, such the earrings below, in the Toscano Collection, owned by Roberto Toscano.

Collecteur’s founders are passionate about the role of the collector in the cultural conversation. They want to shift the terminology of collecting to make it more accessible to those just starting out, as well as those with smaller collections, and those who reject the socially laden label “collector.”

“It’s not really about what you own, or how much you own. It could be one, two, three, or a hundred [works.] But we really want to press this idea of collectors as creative social agents.”[10]

In addition to its social sharing feed, Collecteur includes a magazine with interviews and articles about collectors. The platform is a busy place, with a lot to grab your attention, so it takes a while to get the feel for how to navigate the different areas it provides.

Both CatalogIt and Collecteur provide a new way of viewing private collections. CatalogIt Hub is a quieter digital space, with collections thoughtfully organized in a simple interface. Collecteur is an energetic space for networking where the zeal of creating “a museum created [of] socially conscious collectors”[11] drives engagement.

But will these new platforms find traction and remain viable? The urge to share and be seen isn’t universal. Many collectors prefer to remain private in their purchases, their art relationships, and the extent of their collections. Their reasons range from personal security to simply wanting to move through the world unhindered by notoriety. While both platforms allow the user to select what work is visible, for some collectors concerns about privacy and security may make the idea of public accessibility less appealing.

The labor of maintaining yet another social media presence is also a hurdle. While both platforms offer public visibility as an added benefit to an already digitized collection, the way they’re set up is very different. The CatalogIt Hub provides static visibility that requires little engagement, while the vibrancy of the Collecteur community requires constant engagement, the hallmark of social media platforms. The required investment of time to fully engage with the Collecteur platform may be unappealing to the already busy collector, while the public archive nature of CatalogIt gives the opportunity to share without as much effort.

A last concern regards questions about ownership of data within a digital space, a problematic issue when you consider Facebook and its constant data privacy issues. The questions of who owns the data, image security (in both apps, any user can save images from the database), and how to navigate paywalls (CatalogIt Hub requires a log in, Collecteur requires a log in for additional data) are of concern. Both companies go to great lengths to reassure their users of the safety of their data and use safety measures similar to those banks use to secure client data, but the world of online data piracy is notably nefarious.

However, in spite of these concerns, the possibility of sharing private art jewelry collections remains intriguing, especially within a field that feels unseen by larger art-world conversations. Just as some art jewelry galleries foray into places like Artsy and DesignMiami to broaden awareness of the appeal of art jewelry, the CatalogIt and Collecteur platforms provide a way for individual collectors to share their unique ways of collecting with others who have similar interests. Art jewelry collectors bring a unique eye to the accumulation of objects deserving to be seen and appreciated by like-minded people. Because most collectors of art jewelry collect other art objects as well, a private collection thoughtfully curated for public view could speak volumes to how art jewelry exists in conversation with other objects. These platforms provide a way to make the taste and intelligence of an art jewelry collector seen and appreciated.

Art Jewelry Forum members are already active advocates for art jewelry. From personal acts, like wearing beautiful pieces on a casual outing, to careful curation of their private home collections, they form a community that brings art jewelry into everyday conversations as they live with and wear their collections. Utilizing these new digital platforms from a standpoint of advocacy offers art jewelry collectors the opportunity to expose new audiences outside their personal spheres of influence to the complex wonders of an intimate, well-made, materially experimental piece of art jewelry.

PRICING INFORMATION

CatalogIt: A personal account for private collectors starts at US$120/year, which entitles the account up to 2,500 entries, up to three users, and publishing to the Web via the CatalogIt Hub. See pricing for personal accounts and other account structures here.

Collecteurs: Pricing is structured for monthly subscriptions, free, US$15, or US$125 a month, depending on the number of users and preferred benefits. Details about the benefits of subscription levels are here.

For more information, you can also contact the author, Rebekah Frank.

[1] From an email from Dan Rael and Howard Burrows to the author, February 10, 2020.

[2] For a detailed guide to paper and digital collection management systems written with the art jewelry collector in mind, refer to “Cataloguing Your Jewelry Collection: Everything You Need To Know To Get Started.”

[5] From an email from Dan Rael and Howard Burrows to the author, February 10, 2020.

[9] Here are links to each category: galleries, collectors, collections, and artists.

[10] Scott Indrisek, “Q&A: The Founders of a New Social Network Ask Private Collectors to Share Their Art Online,” Observer, May 1, 2019. https://observer.com/2019/05/collecteurs-jessica-evrim-oralkan-qa/.

[11] Chloe Stead, “Evrim and Jessica Oralkan on Bringing the Art World into the 21st Century,” Freunde von Freunden, November 2, 2018. https://www.freundevonfreunden.com/interviews/evrim-and-jessica-oralkan-on-bringing-the-art-world-into-the-21st-century/.