Born in Jerusalem, the internationally renowned jewelry maker and artist Attai Chen received his undergraduate degree from the Belazel Academy of Art and Design. After graduating, he moved to Munich, where he studied under Otto Künzli at the Academy of Fine Arts. Chen received numerous awards including the Herbert Hofmann Prize (2011), the Oberbayerischer Prize for Applied Arts (2012), and the Andrea M. Bronfman Prize for the Arts (2014). His jewelry can be found in many museum and private collections worldwide. Chen is survived by his partner of 15 years, Carina Shoshtary, as well as his mother, father, stepfather, and two sisters. AJF offers its sincere condolences to all who knew him. The jewelry field has lost an extraordinary talent.

AJF welcomes additional remembrances from the community. Please submit yours here; this page will continually be updated as we receive remembrances.

I am so proud and so grateful to have known Attai Chen—grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with him, to do projects, to participate in the evolution of his work.

Pars pro Toto was the title of the great exhibition I had the pleasure of hosting. A part for the whole. A part to represent the whole. When a part can no longer represent the whole, we lose the opportunity of a specific and precious point of view.

When that missing part is an artist, then we not only lose the man, we lose a suggestion, a chance to understand through his art the complexity of the whole. Thank you to Attai Chen for his suggestion, for his precious point of view. I will remember his beautiful work and his kindness.

—Antonella Villanova. Villanova’s eponymous gallery is located in Florence, Italy. Pars pro Toto, Chen’s solo exhibition there, took place October 16, 2021–January 22, 2022.

Fragile and at the same time ductile, perishable yet immortal, paper was the main medium used by Attai Chen in his artistic practice, which was based on a meticulous and tireless process of painting, cutting, assembling: cyclical gestures religiously perpetuated as a sort of mantra, as a sort of secular prayer from which a new vision recurrently blossoms.

An instinctive imaginative flow guided him in the creation of weightless, colorful, and dynamic high reliefs as well as micro wearable sculptural wonders, both pervaded by a sense of great exuberance yet dignified composure, and by a timeless poetic.

In Attai’s hands, paper also became a means to symbolize the cyclicality of life and of creation: the birth, the growth, the progressive decay, the transformation, and finally, in germ, the starting point for a new beginning.

Today, I would like to glimpse this moment as the beginning of a new eternal spring for Attai and for his exploration into the mystery of imagination, which he so discreetly investigated and respectfully managed to grasp. He gives us the legacy of his so sensitive and yet so wise approach to art and existence, searching for the enchantment in simplicity, the consistence in lightness, the “joy in labor,” the freedom in knowledge.

Blossom by blossom the spring begins. (Algernon Charles Swinburne, “Atalanta in Calydon”)

Attai’s art will continue to blossom (and to bless us) over here, over there, over time.

With respect and gratitude,

—Emanuela Nobile Mino. Nobile Mino is a professor of design history at University La Sapienza, Rome, and a deeply respected curator for contemporary art and design. She curated Pars pro Toto, Chen’s solo exhibition at Galleria Antonella Villanova.

The jewelry community has lost an exceptional human being and an artist of great originality and accomplishment.

Attai Chen was a sabra, or native Israeli, born in Jerusalem in 1979. His work was molded by his studies at Jerusalem’s Bezalel Academy of Art and Design and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, under Otto Künzli. In 2007, Attai began living and working in Munich but maintained close ties with his family and his country.

His work often dealt with Israel’s enduring conflicts while rejecting a polemical/one-sided view in favor of a clear-eyed sense of justice and morality. He introduced Israeli-Palestinian tensions into his work in 2008 when he carved a brooch depicting the Israel Defense Forces’s D9 armored bulldozer, which is used to clear mines. His use of olive wood can be interpreted as a plea for peace, a commentary on the complicated use of the D9, which was also used to demolish the houses of Palestinians and wanted terrorists. The clash of cultures was also represented in his Kalashnikov Pendant (2008), in which entangled patterns formed by miniature rifles create an unresolved message, reflecting the complexity of the relationship.

I first met Attai in Munich in 2010, when he won the prestigious Herbert Hofmann Prize at Schmuck with a masterful necklace of recycled paper that is now part of the Susan Grant Lewin Collection at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, in New York. The work represented the recycling theme that appears repeatedly in Chen’s work, in which new life emerges from decay.

While I was living in Israel a few years later, I knew that I had to include Attai in a project focused on Israel’s contemporary jewelry artists and their deeply felt political, social, and individual convictions. I chose his 2015 brooch in which an intentionally romanticized view of Arab villages clinging to the hillsides around Jericho belies the hidden hardships that were the everyday reality.

In Attai Chen, a rich and compassionate vision has been lost. We can treasure the brilliant sculptures and jewelry objects he produced, but only regret what directions his inventive mind might have explored.

—Ursula Ilse-Neuman. Ilse-Neuman is curator emerita at the Museum of Arts and Design, New York, where, as curator from 1992–2015, she organized more than 40 exhibitions in all media.

My first encounter with Attai Chen had a providential quality. It was 2014, and I was in Israel, my first time in the country. Attai by then was living in Munich, but had just won the Andy Prize for Contemporary Art, offered by the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. It just so happened that his opening coincided with my visit. Imagine my surprise when I walked into one of the most spectacular contemporary jewelry exhibitions I had ever seen, with custom casework setting off each delicate, charismatic creation, a field of secular reliquaries. I was also able to meet Attai in person, and was immediately taken by his thoughtful, quiet intensity. Here, clearly, was a pure artist who had found his medium—and was reimagining it.

That unexpected gift kept on giving in the decade since. In collaboration with Gallery Loupe, I had the opportunity to engage in a long-running conversation with Attai, one of those rich and sustaining dialogues that critics live for. We talked about many things: the way that perspective orders (and restricts) composition; the porous membrane between detritus and the Duchampian found object; theatricality, both in the sense of a proscenium stage and a psychological mindset; the strange way that fragility can summon a sense of imposing power. For me, it was an exchange shot through with magical insight, just like his work.

Attai’s passing, tragically young, represents an incalculable loss for the jewelry community. Suddenly, what we all thought was his early work is all there will ever be. We can’t help but wonder, in such a moment, about what wonders he would have gone on to create. Nor can we help but feel, deeply, the loss of such a beautiful soul. At the same time, we can be grateful for the small miracles he wrought. I hope all who read this set of remembrances of Attai will take a moment to hold one of his pieces, in the hand or in the mind, and say a quiet farewell—and thanks.

—Glenn Adamson. Adamson is a curator and writer who works at the intersection of craft, design history, and contemporary art. He has previously served as director of the Museum of Arts and Design; head of research at the V&A; and curator at the Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee.

I was introduced to Attai Chen by his teacher and mentor, Israeli artist Vered Kaminski, who knew him as a student at Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, Jerusalem. She told me that I had to meet Attai because his work was so impressive. At the time, Attai was a young and promising artist living in Germany and studying at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich. In March of 2010, we met for drinks during Schmuck, at the International Trade Fair in Munich. I was immediately drawn to his work, seduced by the colors, materiality, and fabrication. I couldn’t wait to represent Attai, and he very soon became an integral part of Gallery Loupe.

Over the years there were several solo exhibitions, fairs, and artist talks. His work resonated deeply with all who had the privilege of experiencing it. Attai’s pieces are intricate narratives that intertwine colors, forms, and a unique sense of individuality. Each time we announced a new exhibition of his work, there was excitement. Attai’s pieces had the ability to captivate and engage, always sparking conversations and emotions. His talent was exceptional and his dedication to his craft was unyielding.

Personally, Attai was much more than an artist to me. He was a dear friend. I tend to ask a lot of questions, and Attai was always happy to talk about his work; we were never at a loss for conversation. Over the years, this led to a close personal bond. One especially fond memory is of Schmuck 2019, when Attai and I visited galleries and pop-ups together all over Munich for an entire week, hoping to find a venue for a future group exhibition featuring Attai, Kiff Slemmons, and Thomas Gentille. Little did we know that COVID would change everything, including the opportunity to present exhibitions for the next few years.

A life cut short is tragic. There was still so much more to come for Attai: a new body of work featured in a solo exhibition at Gallery Loupe; a monograph published by Arnoldsche Art Publishers, Stuttgart, with an essay by Glenn Adamson; and beyond that we’ll never know. As I reflect on Attai’s life and work, I am reminded of the vibrancy and vitality he brought to the gallery. The void left by his departure is palpable—but while he may no longer be with us in person, his work will continue to inspire, intrigue, and provoke thought, ensuring that his legacy endures.

—Patti Bleicher. Bleicher co-founded Gallery Loupe in 2006. The gallery, which focuses on contemporary art jewelry, is located in Montclair, NJ, US.

People would sometimes confuse me and Attai. We would be standing right next to each other, dressed differently, beards groomed at different lengths, but still they would struggle to differentiate between us. One time it was one of his gallerists as I stood in Attai’s show in Munich. He couldn’t understand why I was refusing to speak to him in German. Another time it was during a five-minute exchange with someone who didn’t even seem to mind that they were yelling at the wrong person. I’ll miss these mix-ups.

It feels like we hadn’t seen each other in such a long time. The pandemic was very hard on many of us for different reasons. Attai and I had talked about doing a lot of things together. I haven’t been to Israel since I was 10 or 11 and he thought we should go back for a visit together. He really loved his time in Greece and wanted us to visit with him and Carina the next time they were there. We also both thought Sweden would be a great place to live because we both loved all the Swedish people we knew.

When he was in New York or New Jersey he always came to visit me and Erin, and when we were in Munich a priority was always getting to spend some time with him and Carina. There was something very easy about our connection, like a sibling you didn’t know you had—so much in common but also so much to learn.

When I first met Attai, I was actually very anxious about meeting him. Attai was coming to Brooklyn Metal Works for the first time and offered to demonstrate how to use a mouth blowtorch, a torch that is romanticized in the US even though it is super practical in the rest of the world. I wanted everything to be perfect and to make a good impression; we both really loved his work. When Attai showed up, immediately all my fears dissolved. He was just so nice and easygoing.

He had forgotten his mouthpiece, but a random little bit of hose I had lying around the studio would be perfect. I wasn’t sure what fuel gas he needed, and he didn’t know the English word for it, but he felt that if I thought propane was right, he was sure it would be fine. He just needed a little bit of silver and a little of this and that … and everything was great.

From the beginning, Attai was nothing but warm, friendly, no ego, no demands, no rushing, no yelling. He was just this lovely human who was happy to be there with us at our studio. The talk was great, the people were mesmerized by his demonstration—everyone had so many questions and he was so generous and relaxed and excited to see us all.

And he never changed. Every time we saw each other he never changed. He just loved spending time with us, he was always warm and always kind. I will still do many of the things we planned to do together. We have already been to museums and restaurants since he left us. I imagine him with me now because I love thinking of his excited responses to the different languages and foods in NYC. I enjoy thinking about how he would respond to the different art I see and different people I meet. It brings me a lot of happiness to think of how he was and will always be, as he travels with me and everyone who had the joy of knowing him.

—Brian Weissman. Weissman is the co-founder of Brooklyn Metal Works, a co-working metalsmithing studio, education lab, tool shop, and exhibition space. He regularly participates as a juror for exhibitions at various organizations. He was on the selection committee for 45 Stories in Jewelry, at the Museum of Arts and Design. Weissman is also a practicing artist and metalsmith with works in both public and private collections.

The Bird Who Wanted to Be a Cloud

I

Once upon a time there was a woman who broke her arm. She was a goldsmith, and so passionate about making jewelry that she just couldn’t and wouldn’t stop. However, working with her left hand proved to be no easy task, because it was her good right hand that was no longer any use. For all that, Barbara, as she was called, was generally able to wrest something good even out of the most desperate situations in life. She decided to rise to the challenge and find ways of temporarily coping using only her left hand. The first steps are always the hardest and awkward, but Barbara was so keen to share the delight she derived from her new experiences with friends and workshop colleagues that she badgered them into taking part in a joint experiment and voluntarily forgoing the use of their good hand. The undertaking for the right-handed participants was called “Nur mit Links (Left Hand Only),” and for the left-handed members, “Nur mit Rechts (Right Hand Only)”!

II

One of the participants in this experiment was the left-handed designer Attai Chen. He fastened a sheet of cardboard onto his workbench, took a sharp knife in his right hand, and cut an obtuse angle into the cardboard. The cardboard stood up slightly along the cutting edge, formed a sharp edge, a ridge. At precise intervals Attai proceeded to make a series of cuts one after another, all virtually parallel, and observed what happened. He varied the depth of the cuts, the angle, the direction, and the length. He made short, scale-like cuts, used the cutter to create straight, long radial lines resembling fans in the cardboard, but also disorderly, seemingly random cuts. Though initially stiff, the cardboard now became flexible, could be bent, arched, and twisted. The cuts gaped open, the cardboard showed its wounds. In order to emphasize the difference between the outer “skin” and the notches he had added, Attai applied color to the surface of the cardboard, and painted and wrote on it before he let the steel glide through the cardboard, creating an interplay between interior and exterior. A flat surface was transformed into a three-dimensional body and was reincarnated as undulating, intertwined, rhythmically structured components cut and shaped in different ways to create an endless variety of compositions. In the course of the work process, Attai discovered a new formal language, a new, complex vocabulary with an infinite number of possible combinations. Controlled variations, specific repetitions, deliberate expansions were constantly added. And his left hand had already long since become involved. The experiment had served its purpose—”Nur mit Rechts (Right Hand Only)” was over.

III

Munich, summer 2013. The sky is blue. Individual white cumulus clouds are gathering on the horizon. People laugh in the sunshine, fill their lungs with warm air and its heavy scents. I am also in a good mood. Down in the deepest basement of the Pinakothek der Moderne, the so-called Danner Rotunde, I am missing out on the summer. Yet my mission makes this loss worthwhile. I have the pleasant task of arranging the permanent presentation of the jewelry collections of Die Neue Sammlung, The International Design Museum Munich, and the Danner Foundation. When everything is said and done, some 296 jewelry items by 139 artists from 26 countries will be showcased in 35 display cabinets. The finest of everything.

IV

Attai has works on show. In a narrow wall cabinet that extends from the floor to the ceiling, I had two of his cardboard works mounted at eye level against a shimmering background of gray silk. During my descents into the catacombs of the museum I encounter them several times a day, at times only fleetingly, barely lingering, as there is still so much to do. However, often I do stop, take yet another close look at the two brooches. And they never cease to fascinate me. I want to write about them, only about them.

V

Well, I could ask Attai what his intention was with his works, what he wanted to express, I could let him explain his work to me. Then again, would that not be tantamount to mistrusting his artistic expression, his visual power? Or put differently, would it not also amount to failing to rely on my own perception, my integrity and personal experience? So instead I will endeavor to gain my insights through simply observing.

VI

The Free Radicals, from 2011, is a brooch the size of a child’s hand. The composition consists of a rather amorphous, cloud-like core surrounded by a wreath of diverging beams. As in an explosion, feathery bundles break out of the thunder field at the center. Flashes of lightning emerge from the smoke. Mighty forces are at work; there is seething, hissing, and crashing. You feel tempted to seek cover but cannot bear to turn away from the sight of the catastrophe, because it is so beautiful. The colors are simultaneously bright and dark. Graphite, galena, steel blue, sulfurous yellow, mustard, purple, the green of beetle wings, russet, and dusky pink. The dark sharp lines of the cardboard support cut through the skin of the individual forms. The apocalyptic firework shines with a metallic gloss, a display of vain splendor. New images spring to mind. Does this display herald the phoenix brightly rising from the ashes? Are we seeing the wild contortions of courting birds of paradise? Are these shimmering feathers, a magnificent rosette, or war colors? Is the world exploding into pieces, or is it perhaps an imploding star?

VII

Forgive Me Father for I Have Sinned, from 2012, hovers like a cloud (in the aforementioned showcase) above The Free Radicals. It is a quiet but by no means delicate work. The cuts in the dark yellow cardboard are powerful and deep. The sharp contrast between the painted white surface and the wood-colored cardboard, which is accentuated by the black marks on the skin, call to mind the bark of a birch tree. The traces of graphite indicate that before the material was distorted it had a drawing on writing on it. If it were a crumpled piece of paper (another image that comes to mind) we could smooth it out and restore it to its original state. You might speculate further on the basis of the title, which incidentally is borrowed from Damien Hirst, but I will resist from doing so. The work speaks for itself. Only at first glance do the white color and cloudlike shape confer a sense of peace. This is neither a cotton ball nor a falling downy feather. For all its attractiveness there is something dark and oppressive about this tangled ball, this cracked bark. It is an impenetrable agglomerate, a rampant form of growth, fascinating, alluring and threatening. I see a struggle, pain, and desperation. And from deep within a warm light emerges. This object is sad, strong, and beautiful.

—Otto Künzli, January 2014

VIII

Attai, whenever you laughed and your eyes shone, your friendliness and cheerfulness enveloped us and made us feel warm. This is exactly how we will remember you.

—Otto Künzli, August 2023, translation by Jeremy Gaines. Künzli is one of the most renowned jewelers working today. Swiss-trained and Munich-based, his iconic works include Gold Macht Blind (Gold Makes You Blind) (1980) and 1cm of Love (1995). As director of the jewelry department at Munich’s Akademie der Bildenden Künste between 1991 and 2014, he taught many prominent contemporary makers, including Chen.

Attai was one of the most brillant artists I have ever had the opportunity to meet. His light will always shine in our memories and moments shared together.

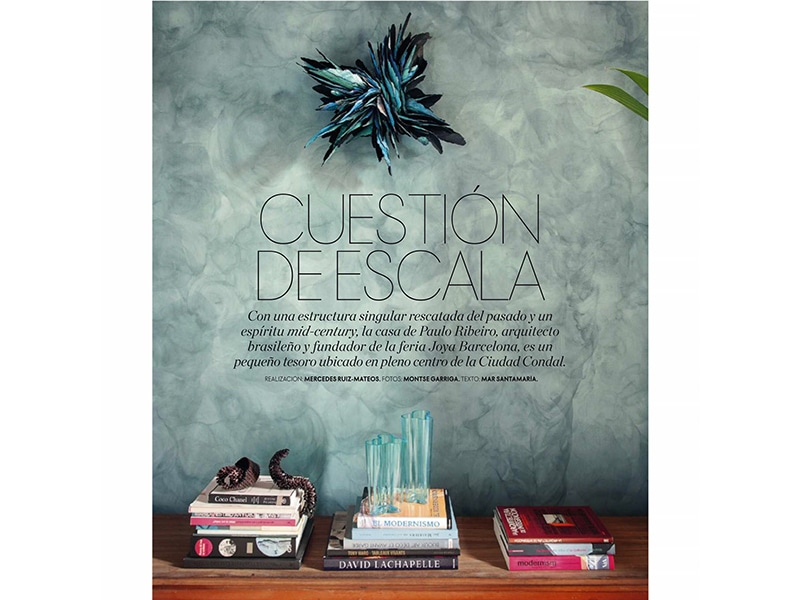

—Paulo Ribeiro. Ribeiro is an architect, a jewelry and art collector, and the director of Contemporania.

We are sad that Attai is gone so early. After a long and important time working together with him, it is very sad to lose this huge talent. He will be missed, along with his wonderful jewelry and his fantastic sculptures. We will miss him as a warm, friendly, and genial colleague.

—Galerie Spektrum, Munich

Beyond the work of this talented and exceptional artist, there was this generous, sensitive human being. We met twice in Munich last March. I didn’t think it would be the last time I’d meet him. Those moments are now engraved in my mind. We hugged. It was only a goodbye. He still had so much to offer us, so much to show us about his talent.

—Noel Guyomarc’h. Guyomarc’h’s eponymous gallery is located in Montreal.

A selection of collections that hold Chen’s work

Alice and Louis Koch Collection of Rings, Swiss National Museum, Zurich

Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts (formerly Arkansas Arts Center), Little Rock, AR, United States

CODA Museum, Apeldoorn, Netherlands

The Donna Schneier Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Helen Drutt Collection, Philadelphia

Museum of Fine Art, Houston, Texas, United States

Museum of Arts and Design, New York

International Design Museum, Munich

Israeli Museum of Art, Jerusalem

Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim, Germany

Rotasa Collection Trust, California

Sanford and Susan Kempin Collection, New York

Susan Grant Lewin Collection, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York

Tel Aviv Museum of Art

© 2023 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org