Contemporary author jewelry is still a rather young phenomenon. Although we can trace its origins back to the days of Jugendstil, its real story starts only some 40 years ago. Under the influence of an increasing economic prosperity things started to gain momentum and especially in the last ten years, developments in the field have accelerated: more and more jewelers enter the market, more and more specialized galleries are opened, more and more schools started jewelry departments, more and more fairs present contemporary jewelry.

But despite the increase in numbers, jewelry still doesn’t count as a serious market where money is made and earned. Author jewelry is not a hot topic—the way design has gained a sexy status. The jewelry scene has an excellent international infrastructure, but on the other hand seems locked up in its self-preferred system. There are complaints, especially among the younger artists: it is impossible for every young maker to find a gallery and how can you make a living out of one solo exhibition every two or three years and some exhibitions abroad? On the other hand, galleries present a platform, introduce artists from abroad, their work and ideas, and bring jewelry from here to fairs abroad and collectors far away.

But there is always this uncomfortable feeling of isolation and preaching to the converted. And maybe I am indebted to this situation, too. There were other writers who resigned and even makers who resigned—because jewelry didn’t seem to make any progress. I stayed and I am part of the system. That is why I thought it would be a good idea to make an analysis of the position of contemporary jewelry today, especially with respect to the market and to finish with proposing possible future scenarios. I have divided my paper into five steps.

First Step: Kisses

In October 1996, Gallery Ra organized the symposium Passion and Profession: Jewelry in Past, Present and Future. Every period needs to investigate its future again and again. At the end of the day, the discussion leader wondered about the future: “What will become of you all? Will it all stay the same, 60 hugging and kissing goldsmiths, or will something happen?” Well, 12 years later we are still hugging and kissing each other, that’s true. And you may wonder what happened in between. Did something happen indeed? Of course, computerized techniques are now widely applied, we have a very well-organized Internet information center called Klimt02, but author jewelry didn’t break through. It didn’t succeed in branding and marketing, the jewelry scene didn’t invent a young and fresh art-wise Cartier or Van Cleef & Arpels or an alternative to Prada and Gucci. And the public, the buyers and wearers, are aging.

Therefore questions about credibility and viability recur with cyclic regularity. You may wonder if author jewelry really needs to break out of its secluded niche and if this kind of jewelry really is a lost case as some people think. You may argue that its value is precisely in the handwork, in the uniqueness, in the creation of attention, concentration, time and rest. But it depends on how you deal with these qualities and values in terms of how they are received in the outside world. These values are now often seen as repulsive and anachronistic, but they can be changed to become up-to-date, contemporary and progressive. If we want more, if contemporary jewelry really wants to reach another public, preferably an art public—because art is the thing most of you feel related with—or a design public—especially now design is proclaimed as a new form of art, more attractive, accessible, and understandable than most contemporary art—how should you do this? What strategies do you have? How do you kiss and entice the public and shake it awake?

Second Step: Faith

We all know the work of Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum, their white elastic suits called Clothing Suggestions (1970). Those suits and the happening, with friends of Gijs and Emmy and the artists themselves showing the suits in an empty gallery instead of a regular exhibition with objects in a showcase, promised a new attitude towards jewelry. Like the big wearable pieces Gijs and Emmy had been designing since 1966, those pieces were presented in the very first catwalk jewelry show that was held in the Stedelijk Museum, that “temple” of contemporary art. It took place in 1967 and it was a very unusual event. It took the designers some effort to convince the museum about its necessity. For me, those events are a highlight in the young history of contemporary jewelry. In a recent exhibition at the V&A in London called Cold War, this work is interpreted in the light of fear and anxiety, as armoring for the body, as a protection against unknown but certain attacks from outside. It is an interesting interpretation but I’d like to stress the immense positive message of these designs: the advance to sculpture and the fusion of body, clothing and adornment into one thing. It expressed an optimistic outlook. It presented something new and innovative at that time and it is still new today.

So where did you get since then and where do you want to be in, let’s say, ten or twenty years from now? What are your “preferred situations” or “desired goals”?

In the past 20 years I have learned some things about jewelers. One is that, in general, jewelers are not designers, they are not designing the way designers do. Apart from some exceptions to the rule, jewelers are do-ers but slow-do-ers, makers but slow-makers, finders, people trying out, doing things over and over again, people who want to know everything about the materials they use. Jewelers are material boys and girls. But it doesn’t need to stay like this forever. Perhaps now is the time to focus on the market as well, to capitalize your talents—your excellent knowledge of materials, forms, and techniques, your capability to work with precious materials. If some succeed in this, others can do it as well.

Another thing I have learned about jewelry is that jewelers are not very communicative. Their work is not created to tempt their buyers. And also in that sense jewelry cannot be compared with design, which is overtly designed to seduce the buyer by its use of color, form, and market strategies. That is why everybody wants the newest iPod and iPhone—they are designed to overrule all rational decision-making, they are bought on an impulse. Jewelry on the other hand, tries to convince. Jewelry is a matter of faith. You have to believe in it before you purchase it. But you can stir this faith by clever communication strategies.

Third Step: Shine

We all know the work of Damien Hirst and the story of the diamond-covered For the Love of God, which attracted more than 100,000 visitors to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam last year. Diamonds are bling bling and 8601 diamonds on a platinum skull are hyper bling bling. The “spin” around this work was excellent, starting with the origin of the skull, the story of the making, the spectacular use of numbers (more than 8,000 diamonds worth between 80 and 100 million euro, not to mention the price of making, which was about 17 million euro) the way it was sold (to a consortium of investors and Hirst himself) the merchandising (T-shirts, buttons, and the like) and the related sales records at Hirst’s Sotheby auction in September (a cool 100 million euro)—just before the financial crisis, lucky for them.

Why is this work so successful? I think there are two reasons. The first is that the artist and his team are very good in manipulating the media. For the Love of God is a typical information-age artwork, it is carried along on a flow of hype around the artist. The media lap it up and the people love to read about it. We live in an age of increasing numbers. We have never had more possessions then we have now; we have never had more stars, VIPs, and millionaires than we have now; we have never had more opportunity to hear about the delirious excesses of those who can afford it. And we have never enough, we want more: more stories, more comfort, more electronic toys, more innovations, more money, more diamonds. So Hirst’s bejeweled skull is reflecting the spirit of our time. It was hyped at the right moment, using the best media strategies.

The second reason for the success is the artistic quality of For the Love of God. It is an excellent piece of art, set with diamonds into the deepest parts of the eye sockets, the nose and the inside of the skull. Hirst didn’t choose the easy way. Every detail of his work is very well considered, including the use of the real set of teeth with one missing tooth, and the skills of the artisans from jeweler Bentley & Skinner. In fact part of the attraction of the work lies in its craftsmanship, the magic of all those diamonds set by hand. The references to well-known memento mori paintings and objects provide the work with an academic framework—for the connoisseurs who now have an alibi to simply enjoy the shine of this work of art. Rudi Fuchs called it “a piece of extraordinary, mad artistry.” In other words, this art object is a great work of art because it is the most talked-about artwork in ages and because it succeeds in enticing all ranks of our society.

What can we learn from this? Well, that there are certain things that attract people, things like uniqueness, craftsmanship, shine, and preciousness—things you can easily handle as a jeweler, things you can all deal with as jewelers, whenever you like.

Fourth Step: Fame

A relatively new phenomenon is that of selling your work at auction. For some time, design has been selling tremendously well at auctions and fairs—prices of more than 150,000 euro for a design chair or cabinet are not exceptional anymore. But prices have to do with fame and uniqueness. Old design from the 1930s to the 1970s sells because of a famous name and because of its rarity. New design sells because of fame and uniqueness—a design object in an edition of seven sells as a “unique piece.”

There are also fine artists who have started to have auctioneering firms as their exclusive dealers, like Damien Hirst and Sotheby’s, or Annie Leibowitz and Phillips de Pury in London. Sometimes auctioneering firms have a gallery and the exclusive rights of sales, like La Galerie de Pierre Bergé in Brussels. The gallery commissioned Dutch designer Jurgen Bey to design a new collection of furniture-like art objects and sells them as unique pieces in an edition of two, three or four. Even his Sheep Jumping over the Fence, Stool and Apron, made in an edition of twelve, are sold as unique pieces.

In contemporary art and design things are moving, that is clear. Therefore it’s a pity that this relative young development is now surpassed by the financial and economic crisis. Now that the fortune of many Russian, Asian, and dot-com moneybags is vaporized, how do auctions deal with this? Last month the atmosphere at the great London auctions was rather tame and the Frieze Art fair in London and Design Miami were not very successful as well.

And what about jewelry? Since last year there have been Brussels auctions by Pierre Bergé, who cares about contemporary jewelry and organized two jewelry auctions to date. That’s good news—perhaps. Jewelry is collected fromthe artists, sometimes from galleries but most of the galleries feel no enthusiasm to cooperate and you can’t blame them. It has been something strange indeed to see new jewelry in a lousy showcase, when you just recently saw it in a gallery context. It may look like heaven for the bargain hunter, as well as for the artists who earn more when they sell at the auction compared to the gallery. But these are all short-term successes. Auctioneering firms are businesses, they won’t promote young and unknown artists and they only believe in success. And besides, you can’t live from one sold piece, once or two times a year. The sales at the second Brussels auction—in December in the middle of the financial crisis—were not spectacular. More than half of the lots were not sold, and those that did sell just reached the low estimate price. The sole moment when the room became more active and something like an atmosphere of greed was apparent was when the last lots came under the hammer: a jewel by Hans Arp (one of an edition of 100) and one by Man Ray. It was again the old mechanism of the name and fame of the artist that was the main sales argument here.

Fifth Step: Luxury

But how can you possibly stimulate your sales then?

A position you can take is that of the underdog. You reconcile to the situation. You agree you are not famous, you say you don’t like and need to be famous and you try to conquer another market, the one of the broad public and sell at fairs and in shops. To do this successfully you need to make concessions. You can’t present your work in the same way that you do in a gallery context. It needs an explanation, it needs little incentives that invite people to come nearer: a specially made edition, a colorful or shining “take-away” jewel that is like a treat. I think it is perfectly fine to work like this, but take care: it is not easy at all and the jewelers who are in this position know exactly what I mean.

Others address to the world of fashion, which is a fascinating and interesting market. The fashion world is interested in experiments, in innovative materials and typologies. If you really go into it you will see that here are striking similarities between fashion jewelry and “our” kind of jewelry and that there is a world to conquer. Like fashion, jewelry can be presentational. The British Naomi Filmer did catwalk collaborations with different and prolific British fashion designers such as Hussein Chalayan. In 2001 she designed glass and silver balls to fix the hands of the models to their backs while showing Alexander McQueen’s fashion collection—with the aim of making them assume the posture of a flamenco dancer. Her approach is conceptual and she also worked with video, photography, and sound, with chocolate and ice. Besides that, she works as a designer for companies such as Armani and Burberry. There is nothing adventurous about that work, but Naomi knows how to work on different tracks, getting her work published in fashion, art, and jewelry publications.

For some years the Austrian company, Pierre Lang, has organized the So Fresh Jewelry Award, an interesting mix of fashion, art and design. This is a new opportunity to get your work seen and appreciated in the context of fashion. But remember, applying means rethinking your work and aims, thinking out of the box.

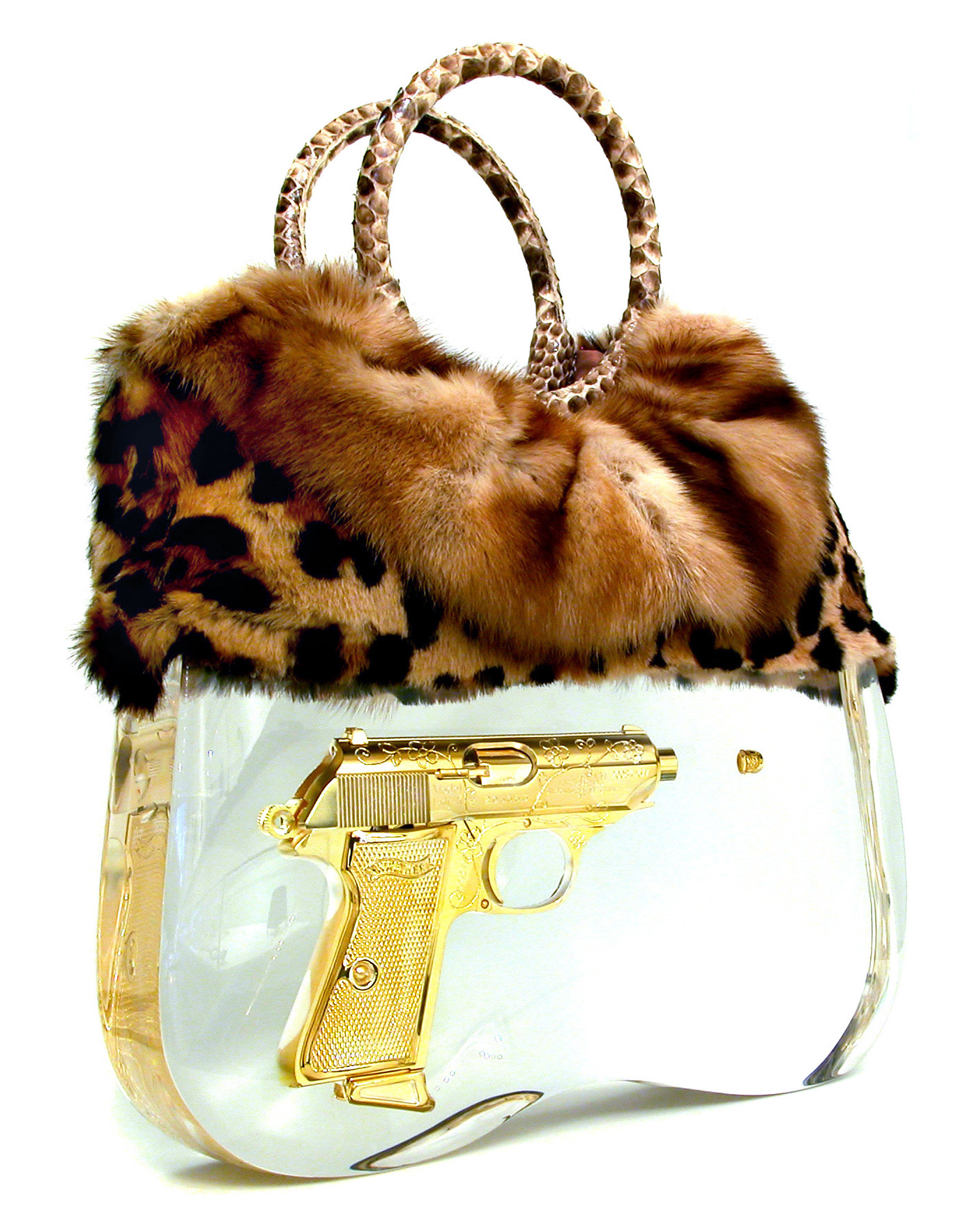

To infiltrate the world of conventional jewelry is another option that finally—after having been dismissed by the art jewelry scene for decades—seems accepted now. We all know that people are like magpies who love sparkles. People are even willing to transform the ashes of their beloved ones into a diamond—diamonds are big business. Why not convert to the diamond? There are cautious signs of a new approach, coming from this other world of luxurious jewelry: jeweler Lyppens here in Amsterdam wants to work with Ted Noten on a new line of black-diamond jewelry. This is a brand new initiative that is still in its infant stage, but has the smell of something new and fresh.

Some years ago a South African diamond mine owner and former architect called Hilton Judin started a project introducing a new line of diamond jewelry called Very Lustre. It is partly designed by people from our scene such as Dinie Besems, Marc Monzo, Hilde van der Heyden, and Karl Fritsch, and partly by interesting designers like BLESS, Studio Job, and Adam und Harborth. The idea is to be both “exclusive and accessible, bold and withdrawn, valuable and ordinary.” As Hilton Judin states, Very Lustre is “a common standardized but intricate collection of diamond jewelry based on concepts and statements, produced in collaboration with several independent authors.” It is a pity that you can’t find much information about this new jewelry collection. After meeting Hilton Judin some years ago at the Milan Furniture Fair, where he showed me the first prototypes from Marc Monzo, I have never been able to reach him again. The designers I spoke with have had the same experience: the last they heard is that the jewels are sold in Comme des Garcons Guerrilla Shops and that Hilton Judin is still going on with this project. Anyway, this fusion of diamonds, fashion, and design, of luxury and concept, is a fascinating example of how worlds can merge in today’s society.

If the diamond is not your thing, you can also focus on other gems, synthetic or natural. This is what Truike Verdegaal is doing with her Maria Lux line of “prêt-a-porter” jewelry. This project was encouraged by contact with Lilian Driessen, a fashion and accessories designer in Amsterdam. In all these years Verdegaal has learned not to expect too much from having her own label, but she also experienced that the moment you really start working on it and you enter the world of the glossy magazines, things can really go fast. It is the power of numbers and multiplication that counts.

I am convinced that our boxed-in jewelry scene will start changing pretty soon. It can’t stay the way it has been the last 40 years. Our society has changed and so the jewelry scene will change. In the near future jewelers will work on different tracks: for the gallery and for their own label, the fair, Internet sale, house sale parties, or any other initiative. The jeweler as a businessman: why not? But therefore connections between artists and galleries and clients should be more rational and businesslike. A jeweler is an artist who creates a product and wants to sell it. He/she has something unique to offer, something handmade, thoughtfully made and carefully made, in very small editions, or more often completely unique and made from precious or special materials. This is your capital. I strongly believe in what fashion designer Alexander van Slobbe, the new artistic director of the design Academy in Eindhoven, says: “The new luxury is that of the small-scale, the hand-made, and permanence.”

The gallery is the in-between salesman who wants to sell this luxury product. This is business, not an altruistic affair. Perhaps it once was, but times have changed and it is now time to re-invent author jewelry. The numbers of jewelers, galleries, fairs, and other initiatives and opportunities are growing—complexity will grow with the numbers. And so you will have to rationalize your connections and look for new collaborations. You need contracts, clear agreements, more openness, and room for negotiations and initiatives of the artists that go beyond the confines of the gallery. You should try to work on different tracks. In the end all parties will profit from it.

Complexity opens up new possibilities. I think it is time to step out of the comfort zone and make yourself seen.

***

EL PODER DE LA JOYERÍA

por Liesbeth Den Besten

Esta conferencia se presentó en Out of the Box, un simposio organizado por la Fundación Françoise van den Bosch en el Museo Stedelijk-Hertogenbosch, el 11 de enero de 2009.

La Joyería contemporánea de autor es un fenómeno muy joven. Aunque podemos rastrear que sus orígenes se remontan a los tiempos de Jugendstil, su verdadera historia empieza hace unos 40 años. Bajo la influencia de una creciente prosperidad económica las cosas comenzaron a ganar impulso y, especialmente en los últimos diez años, los avances en el campo se han acelerado: más y más joyeros se incorporan al mercado, más y más galerías especializadas abren sus puertas, más y más escuelas fundan departamentos de joyería, más y más exhibiciones presentan joyería contemporánea.

Pese al del incremento en los números, la joyería todavía no cuenta como un mercado serio donde se hace y se gana dinero. La joyería de autor no es un tema candente – no de la manera como el diseño si ha ganado un estatus atractivo. La escena de la joyería tiene una excelente infraestructura internacional, pero por otro lado parece preferir estar encerrada en un sistema propio. Existen quejas, especialmente entre los artistas más jóvenes: es imposible para cada creador joven encontrar una galería, y ¿cómo se puede vivir de una exposición individual cada dos o tres años y de algunas cuantas exposiciones en el extranjero? Por otro lado las galerías ofrecen una plataforma, introducen artistas extranjeros, sus trabajos e ideas y además se llevan joyas locales a exhibiciones en el extranjero y a coleccionistas lejanos.

Pero siempre hay esta sensación incómoda de aislamiento y predicar a los ya convertidos. Y quizás, yo también estoy en deuda con esta situación. Han habido otros escritores e incluso otros creadores quienes renunciaron porque en la joyería pareciera que no ha existido ningún cambio. Yo me quedé y soy parte del sistema. Por eso pensé que sería una buena idea hacer un análisis de la posición de la joyería contemporánea hoy en día, especialmente con relación al mercado y terminando con una propuesta sobre posibles escenarios futuros. He dividido mi artículo en 5 pasos.

Primer Paso: Besos

En octubre de 1996, Gallery Ra organizó el simposio Profesión y Pasión: La joyería en el pasado, presente y futuro. Cada período necesita investigar su futuro una y otra vez. Al final del día, el líder de la discusión preguntó sobre el futuro: “¿Qué será de todos ustedes? ¿Se mantendrá todo igual, 60 orfebres abrazándose y besándose, o algo sucederá? ” Bueno, doce años después, aún nos abrazamos y nos besamos, eso es cierto. Y puedes preguntarte si algo sucedió mientras tanto ¿sucedió algo realmente? Por supuesto, las técnicas computarizadas son ahora ampliamente aplicadas, tenemos un muy bien organizado centro de información por internet llamado Klimt02 pero, la joyería de autor no ha logrado abrirse paso. No ha logrado tener éxito en el mercadeo y en el posicionamiento como marca, la joyerìa de autor no ha inventado en términos artísticos un joven y fresco Cartier o Van Cleef & Arpels o una alternativa a Prada y a Gucci. Y el público, los compradores y los usuarios, están envejeciendo.

Por lo tanto, las preguntas sobre la credibilidad y la viabilidad se repiten con regularidad cíclica. Te puedes estar preguntando si la joyería de autor necesita salir de su nicho aislado y si este tipo de joyería realmente es un caso perdido como piensan algunas personas. Puedes argumentar que su valor está precisamente en el trabajo manual, en la singularidad, en la creación de atención, concentración, tiempo y descanso. Pero depende de cómo tratas con estas cualidades y valores en términos de còmo se perciben en el mundo exterior. Estos valores se ven a menudo como repulsivos y anacrónicos, pero se pueden cambiar para convertirse en modernos, contemporáneos y progresivos. Si queremos más, si la joyería contemporánea realmente quiere llegar a otro público, preferiblemente a un público artístico – porque es el arte con lo que más se siente relacionada – o a un público de diseño – especialmente ahora el diseño se proclama como una nueva forma de arte, más atractivo, accesible y comprensible que la mayoría del arte contemporáneo – ¿Cómo debería hacerlo? ¿Qué estrategias tiene? ¿Cómo besar y atraer al público y despertarlo?

Segundo paso: Fe

Todos conocemos el trabajo de Gijs Bakker y Emmy van Leersum, sus trajes elásticos blancos llamados Sugerencias de Vestimenta (Clothing Suggestions-1970). Esos trajes y el happening con Gijs y Emmy y sus amigos mostrando los trajes en una galería vacía en lugar de una exposición regular con los objetos en un escaparate, prometió una nueva actitud hacia la joyería. Al igual que las grandes piezas para vestir que Gijs y Emmy habían diseñado desde 1966, esas piezas fueron presentadas en el primer desfile de joyería que se celebró en el Museo Stedelijk, ese “templo” del arte contemporáneo. Se realizó en 1967 y fue un evento muy inusual. A los diseñadores les tomó algo esfuerzo para convencer al museo de su necesidad. Para mí, esos eventos son un punto culminante en la corta historia de la joyería contemporánea. En una reciente exhibición llamada Guerra Fría (Cold War) en el V&A en Londres, este trabajo se interpreta la luz del miedo y la ansiedad, como blindaje para el cuerpo, como una protección contra ataques desconocidos, pero seguros desde el exterior. Es una interpretación interesante, pero me gustaría destacar el inmenso mensaje positivo de estos diseños: el avance en la escultura y la fusión de cuerpo, ropa y adorno en una misma cosa. Expresó una perspectiva optimista. Presentó algo nuevo e innovador en ese momento y todavía hoy continua siendo nuevo.

Entonces, ¿A dónde has llegado desde entonces y dónde quieres estar, digamos, dentro de diez o veinte años? ¿Cuáles son tus “situaciones preferidas” o “metas deseadas”?

En los últimos veinte años he aprendido algunas cosas sobre los joyeros. Una es que, en general, los joyeros no son diseñadores, no están diseñando la forma en que los diseñadores lo hacen. Aparte de algunas excepciones a la regla, los joyeros son creadores pero creadores lentos, fabricantes, pero fabricantes lentos, son descubridores, personas que prueban, hacen cosas una y otra vez, personas que desean saberlo todo sobre los materiales que usan. Los joyeros son muchachos y muchachas materiales. Pero no tiene que ser así para siempre. Tal vez ahora es el momento de concentrarse en el mercado también, de capitalizar tus talentos – tu excelente conocimiento de materiales, formas y técnicas, tu capacidad para trabajar con materiales preciosos. Si algunos tienen éxito en esto, otros también pueden hacerlo.

Otra cosa que he aprendido sobre la joyería es que los joyeros no son muy comunicativos. Su trabajo no se crea para tentar a sus compradores. Y también en ese sentido la joyería no puede ser comparada con el diseño, que está expresamente planeado para seducir al comprador por su uso de color, forma y estrategias de mercado. Es por eso que todo el mundo quiere el iPod más nuevo y el iPhone más nuevo – están diseñados para anular toda la toma de decisiones racionales, se compran en un impulso. La joyería por otro lado, trata de convencer. La joyería es una cuestión de fe. Tienes que creer en ella antes de comprarla. Pero puedes provocar esta fe mediante estrategias inteligentes de comunicación.

Tercer Paso: Brillar

Todos conocemos el trabajo de Damien Hirst y la historia de “Por el amor de Dios” (For The Love of God) que, estando cubierto de diamantes, atrajo a más de 100.000 visitantes al Rijksmuseum en Amsterdam el año pasado. Los diamantes son bling bling y 8601 diamantes en un cráneo de platino son aún más bling bling*. El “giro” alrededor de este trabajo fue excelente, empezando por el origen del cráneo, la historia de su fabricación, el uso espectacular de los números (más de 8000 diamantes, entre 80 y 100 millones de euros, sin mencionar el precio de la fabricación (que estuvo al rededor de los 17 millones de euros), la forma en que fue vendido (a un consorcio de inversores y el mismo Hirst), el mercadeo (camisetas, botones, entre otras cosas) y los registros de ventas relacionados en la subasta Sotheby en Hirst en septiembre (unos atractivos 100 millones de euros), justo antes de la crisis financiera, afortunadamente para ellos.

¿Por qué este trabajo tuvo tanto éxito? Creo que hay dos razones. La primera es que el artista y su equipo son muy buenos en la manipulación de los medios de comunicación. For The Love of God es una obra de arte típica de la era de la información, se lleva adelante en un torrente de “bombos y platillos” alrededor del artista. Los medios de comunicación lo reseñan y la gente le encanta leer sobre él. Vivimos en una época de números cada vez mayores. Nunca hemos tenido tantas posesiones como ahora tenemos; nunca hemos tenido tantas estrellas, personalidades importantes y millonarios como los que ahora tenemos; nunca hemos tenido tanta oportunidad de oír hablar de los excesos delirantes de aquellos que pueden permitírselo. Y nunca tenemos suficiente, queremos más: más historias, más comodidad, más juguetes electrónicos, más innovaciones, más dinero, más diamantes. Así que el cráneo lleno de joyas de Hirst refleja el espíritu de nuestro tiempo. Fue promocionado en el momento adecuado, utilizando las mejores estrategias de los medios de comunicación.

La segunda razón del éxito es la calidad artística de For The Love of God. Es una obra de arte excelente, engastada con diamantes en las partes más profundas de las cavidades de los ojos, la nariz y el interior del cráneo. Hirst no eligió el camino fácil. Cada detalle de su trabajo esta muy bien pensado, incluyendo el uso del conjunto real de dientes con un diente que falta y las habilidades de los artesanos joyeros de Bentley & Skinner. De hecho parte de la atracción de la obra radica en su elaboración artesanal, la magia de todos esos diamantes engastados a mano. Las referencias a las conocidas pinturas y objetos del memento mori proporcionan a la obra un marco académico – para los conocedores que ahora tienen una coartada para simplemente disfrutar del brillo de esta obra de arte. Rudi Fuchs le llamó “una obra de extraordinaria y delirante destreza”. En otras palabras, este objeto artístico es una gran obra de arte porque es la pieza más comentada en décadas y logra exitosamente atraer a todas los grupos de nuestra sociedad.

¿Qué podemos aprender de esto? Bueno, que hay ciertas cosas que atraen a la gente, cosas como la singularidad, la manufactura, el brillo y la preciosidd – cosas que uno puede manejar fácilmente como un joyero, cosas con las que todos pueden lidiar como joyeros, es cualquier momento que se desee.

Cuarto paso: La fama

Un fenómeno relativamente nuevo es el de vender una obra en una subasta. Durante algún tiempo, el diseño se ha vendido muy bien en las subastas y ferias – los precios de más de 150.000 euros para una silla de diseño o gabinete ya no son excepcionales. Pero los precios tienen que ver con la fama y la singularidad. El viejo diseño de los años 30 a los años 70 vende a causa de un nombre famoso y debido a su rareza.El nuevo diseño se vende debido a la fama y la singularidad – un objeto de diseño en una edición de siete se vende como una pieza única.

También hay buenos artistas que han comenzado a tener firmas de subastas como sus representantes exclusivos, como Damien Hirst y Sotheby`s, o Annie Leibowitz y Phillips de Pury en Londres. Algunas veces las firmas de subastas tienen una galería y los derechos exclusivos de venta, como La Galerie de Pierre Bergé en Bruselas. La galería comisionó al diseñador holandés Jurgen Bey el diseño de una nueva colección de objetos de arte similares a muebles y los vende como piezas únicas en una edición de dos, tres o cuatro. Incluso sus Sheep Jumping over the Fence (ovejas saltando sobre la cerca), Stool and Apron (Taburete y Delantal), realizados en una edición de doce, se venden como piezas únicas.

En el arte contemporáneo y el diseño las cosas se están moviendo, eso está claro. Por lo tanto, es una lástima que este desarrollo relativamente joven esté siendo eclipsado por la crisis financiera y económica. Ahora que la fortuna de muchos rusos, asiáticos y las bolsas de dinero de las puntocom se evaporan, ¿Cómo harán las firmas de subastas para lidiar con esto? En los últimos meses, la atmósfera de las grandes subastas en Londres fue bastante moderada y la Frieze Art London y Design Miami tampoco tuvieron mucho éxito.

¿Y qué hay de la joyería? Desde el año pasado ha habido subastas en Bruselas organizadas por Pierre Bergé, quien se preocupa por la joyería contemporánea y ha organizado dos subastas de joyas hasta la fecha. Estas son buenas noticias, quizás. La joyería se obtiene de los artistas, a veces de las galerías, pero la mayoría de ellas no sienten ningún entusiasmo en cooperar y no se les puede culpar. Ha sido algo extraño, de hecho, ver joyas nuevas en una vitrina terrible, cuando se le vio recientemente en el contexto de una galería. Puede parecer un paraíso para el cazador de gangas así como para los artistas que ganan más cuando venden en la subasta en comparación con la galería. Pero estos éxitos son todos a corto plazo. Las firmas de subastas son negocios, no promoverán artistas jóvenes y desconocidos y sólo creen en el éxito. Y además, no se puede vivir de una pieza vendida, una o dos veces al año. Las ventas en la segunda subasta de Bruselas -en diciembre en medio de la crisis financiera- no fueron espectaculares. Más de la mitad de los lotes no fueron vendidos, y los que vendieron sólo alcanzaron sus precios mínimos estimados. El único momento en que la habitación se hizo más activa y se creó aparentemente algo parecido a una atmósfera de codicia fue cuando los últimos lotes llegaron bajo el martillo: una joya de Hans Arp (de una edición de 100) y una de Man Ray. De nuevo fue el viejo mecanismo del nombre y la fama del artista la razón principal de las ventas.

Quinto paso: Lujo

Pero entonces, ¿cómo es posible estimular tus ventas?

Una posición que puede tomar es la del subestimado. Te reconcilias con la situación. Aceptas que no eres famoso, dices que no te gusta y que no necesitas ser famoso e intentas conquistar otro mercado, el de un público más amplio y vendes en ferias y en tiendas. Para hacer esto con éxito necesitas hacer concesiones. No puedes presentar tu trabajo de la misma manera en que lo haces en el contexto de una galería. Necesita una explicación, necesitas pocos incentivos que inviten a la gente a acercarse: una edición especial, una joya lista para comprarse o colorida que sea como un regalo. Creo que está bien trabajar así, pero ten cuidado: no es nada fácil y los joyeros que están en esta posición saben exactamente lo que quiero decir.

Otros se dirigen al mundo de la moda, que es un mercado fascinante e interesante. El mercado de la moda está interesado en los experimentos, en materiales y tipologías innovadoras. Si realmente quieres zambullirte en él, verás que existen similitudes entre la joyería de moda y “nuestro” tipo de joyería y es que existe un mundo por conquistar. Así como la moda, la joyería puede ser de exhibición. La británica Naomi Filmer hizo colaboraciones de pasarela con diseñadores de moda británicos diferentes y prolíficos como Hussein Chalayan. En el año 2000 diseñó bolas de cristal y plata para fijarles las manos a los modelos en sus espaldas con el objetivo de hacerles asumir la postura de un bailarín de flamenco mientras mostraban la colección de moda de Alexander McQueen. Su enfoque fue conceptual y trabajó también con video, fotografía y sonido, con hielo y chocolate. Además, trabaja como diseñadora para empresas como Armani y Burberry. No hay nada aventurero en ese trabajo, pero Naomi sabe cómo trabajar en diferentes temas, consiguiendo su que su trabajo sea exhibido en publicaciones de moda, arte y joyas.

Desde hace algunos años, la empresa austriaca Pierre Lang ha organizado el So Fresh Jewelry Award, una interesante mezcla de moda, arte y diseño. Esta es una nueva oportunidad para que tu trabajo sea visto y apreciado en el contexto de la moda. Pero recuerda, aplicar significa repensar tu trabajo y objetivos, pensando fuera de la caja.

Infiltrarse en el mundo de la joyería convencional es otra opción que finalmente – después de haber sido descartada por la escena de la joyería artística por décadas – parece ahora aceptarse. Todos sabemos que la gente es como las urracas que aman las chispas. La gente está incluso dispuesta a transformar las cenizas de sus seres queridos en un diamante – los diamantes son un gran negocio. ¿Por qué no convertirse a la aceptación del diamante? Hay signos cautelosos de un nuevo enfoque, procedentes de este otro mundo de joyas de lujo: el joyero Lyppens aquí en Amsterdam quiere trabajar con Ted Noten en una nueva línea de joyería de diamantes negros. Esta es una nueva iniciativa que todavía está en su etapa inicial, pero tiene el olor de algo nuevo y fresco.

Hace unos años, el propietario de una mina de diamantes de Sudáfrica y ex arquitecto llamado Hilton Judin comenzó un proyecto de introducción de una nueva línea de joyería de diamantes llamada Very Lustre. Está diseñada en parte por personas de nuestra escena como Dinie Besems, Marc Monzo, Hilde van der Heyden y Karl Fritsch y en parte por interesantes diseñadores como BLESS, Studio Job y Adam und Harbourth. La idea es ser “exclusiva y accesible, audaz y retraída, valiosa y ordinaria”. Como Hilton Judin menciona, Very Lustre es “Una colección común y compleja de joyería diamantada basada en conceptos y declaraciones, producida en colaboración con varios autores independientes”. Es una lástima que no se encuentre mucha información sobre esta nueva colección de joyas. Después de conocer a Hilton Judin hace algunos años en la Feria del Mueble de Milán, donde me mostró los primeros prototipos de Marc Monzo, nunca he podido contactarlo nuevamente. Los diseñadores con los que hablé han tenido la misma experiencia: lo último que escucharon es que las joyas se venden en tiendas estilo guerrilla como Comme des Garcons y que Hilton Judin continúa con este proyecto. De todos modos, esta fusión de diamantes, la moda y el diseño, de lujo y concepto, es un ejemplo fascinante de cómo los mundos pueden fusionarse en la sociedad actual.

Si el diamante no es lo tuyo, también puedes concentrarte en otras gemas, sintéticas o naturales. Esto es lo que Truike Verdegaal está haciendo con su línea de joyas ‘prêt-a-porter’ de Maria Lux. Este proyecto fue alentado por el contacto con Lilian Driessen, diseñadora de moda y accesorios en Amsterdam. En todos estos años Verdegaal ha aprendido a no esperar demasiado de su propia marca, pero también experimentó que en el momento en que realmente se empieza a trabajar en ella y se entra en el mundo de las revistas famosas, las cosas pueden ir realmente rápido. Es el poder de l os números y la multiplicación lo que cuenta.

Estoy convencida de que nuestra cerrada escena de la joyería comenzará a cambiar muy pronto. No puede permanecer como ha sido en los últimos 40 años. Nuestra sociedad ha cambiado y por lo tanto la escena de la joyería va a cambiar. En un futuro próximo los joyeros trabajarán en diferentes vías: para la galería y su propia marca, la feria, venta por Internet, fiestas de venta en casas o cualquier otra iniciativa. El joyero como persona de negocios: ¿por qué no? Pero por ahora las conexiones entre los artistas, las galerías y los clientes deben ser más racionales y parecidas a un negocio. Un joyero es un artista que crea un producto y quiere venderlo. Él / ella tiene algo único que ofrecer, algo hecho a mano, consciente y cuidadosamente hecho, en ediciones muy pequeñas, y más a menudo completamente único y hecho de materiales preciosos o especiales. Este es tu capital. Creo firmemente en lo que dice el diseñador de moda Alexander van Slobbe, el nuevo director artístico de la Academia de Diseño de Eindhoven: “El nuevo lujo es el de la pequeña escala, el hecho a mano y la permanencia”.

La galería es el vendedor intermedio que quiere vender este producto de lujo. Esto es negocio, no un asunto altruista. Tal vez fue una vez, pero los tiempos han cambiado y ahora es el momento de reinventar la joyería de autor. El número de joyeros, galerías, ferias y otras iniciativas y oportunidades están creciendo – la complejidad crecerá con los números. Y así tendrás que racionalizar tus conexiones y buscar nuevas colaboraciones. Necesitas contratos, acuerdos claros, más apertura y espacios para las negociaciones e iniciativas de los artistas que van más allá de los confines de la galería. Deben tratar de trabajar en diferentes ámbitos. Al final todos los partidos se beneficiarán de ella.

La complejidad abre nuevas posibilidades. Creo que es tiempo de salir de la zona de confort y hacerte ver.

Liesbeth den Besten es historiadora del arte, residenciada en la región de Amsterdam. Trabaja como escritora independiente, profesora, conferencistay curadora. Actualmente, enseña historia de la joyería en Sint Lucas Antwerpen. Es la presidenta de la Fundación Françoise van den Bosch para la joyería contemporánea, miembro del consejo asesor de la ¿Chi ha paura …? Creadora y miembro fundador de Think Tank, una iniciativa europea para las artes aplicadas. Su libro, Sobre Joyería: Un Compendio de Joyería Internacional de Arte Contemporáneo, fue publicado por Arnoldsche en noviembre de 2011.

Translated from English by Andreína Rodriquez with assistance from readers Barbara Magaña and Mariana Acosta.