Betty Cooke, who lived until her centennial year, was one of the last living links to mid-century modern design. A jeweler and artist of note, Cooke was also a purveyor of well-crafted objects. In this, she influenced the status of good design throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Cooke’s artisanry and signature streamlined aesthetic crossed mediums and included painting, leatherwork, and jewelry. She transcended the boundaries of mainstream adornment through her use of nonprecious metals, natural objects, and asymmetrical forms, which were infused with a sense of movement. Her nearly 80-year career secures her place in the pantheon of a generation.

Cooke was born and raised in Baltimore. Rather than leave to make her future in New York or some other artistic center, she stayed in her hometown and became one of her city’s guiding artistic forces. Influenced by her surroundings in Baltimore, including the collection at the Walters Art Gallery (now Walters Art Museum), Cooke developed into an artist who could channel her creativity to align with contemporary art movements, while also remaining true to her personal relationship with the natural world. What at first glance exudes geometry, upon further reflection seems to encapsulate some element of ecology, whether terrestrial or celestial. The purity of her designs allows her work to communicate immediately with its wearer, and the sometimes surprising material combinations add an element of whimsy and playfulness to her work.

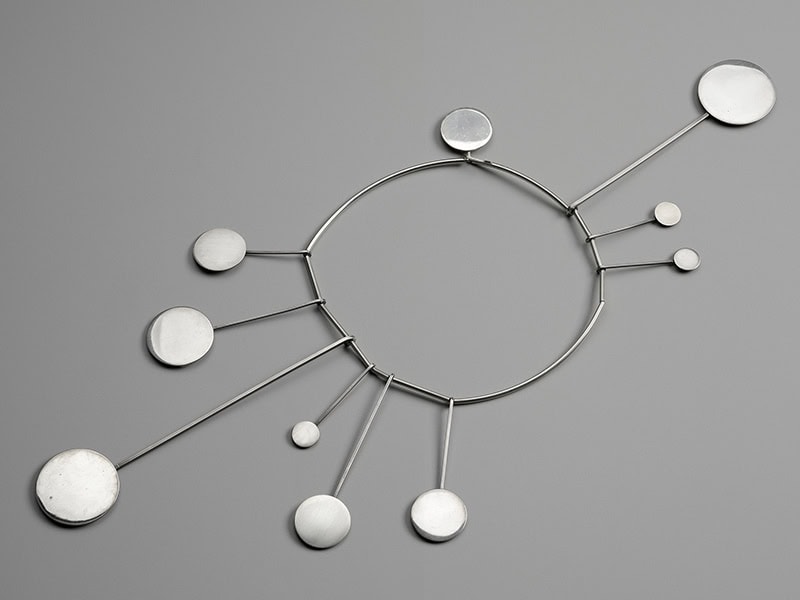

Take for example the necklace above, comprised of 10 flat, round disks of varying sizes. They hang from lengths of silver tubing as pendants. Six of the disks are highly reflective, while four have a brushed, matte finish. They are dispersed rhythmically around a circular necklace. (This sterling silver necklace was subsequently made in other metals.) The composition offers numerous points of entry. It can be read as a percussive study in form, or as a solar system in which the planets’ velocities project them from a shared orbit. Or one might see it as an array of lashes, clumped by a hasty mascara application, circling a voided eye socket. What at first glance seems direct in interpretation offers a surprising number of impressions.

The ability of Cooke’s work to embody so many interpretations fills it with vitality. Its liveliness is accentuated by her frequent use of asymmetry, which takes into account the unexpected ways her work interacts with the body. This “windblown” effect, as Cooke has described it, gives her work an energy and action that the field of jewelry had previously relied on cut gems and precious metals to achieve.

This is evident in the dramatic neckpiece above. A series of pendants rendered in continuous lines of silver (or gold, in another version of the work), hang like weights from a D-shaped necklace. The pendants resemble the ripples of stones thrown in a pond. The nearly immaterial nature of the forms emphasizes the relationship between positive and negative space, creating a surprisingly physical presence.

Cooke

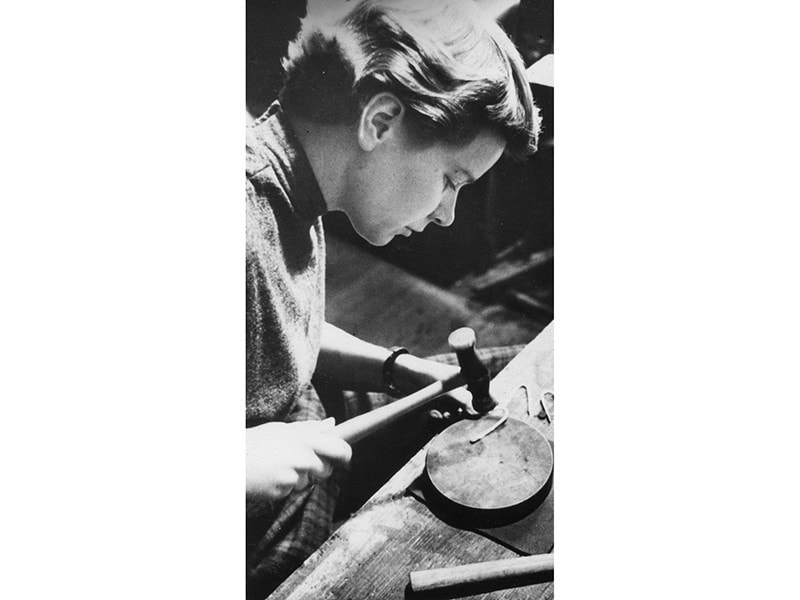

Cooke has been described as an adventurous spirit. Her personal drive and tenacity allowed her to achieve a considerable amount at an early age and sustain her career deep into her elder years. She attended the Maryland Institute of Art (now Maryland Institute College of Art), associated with Johns Hopkins University, where she earned a BFA in art education in 1946. (She attended a summer study at Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1951 to further develop her metalworking skills.) After graduation she joined the faculty at the Maryland Institute of Art, teaching in the design and materials department. She painted, created leatherwork, and made jewelry. Cooke was a bold traveler and sought out new experiences and places, but also used her treks to find outlets for her work. In this manner, she was able to gain representation nationally during a cross-country trip to California by bringing along a portfolio of work samples.

By 1947, just a year after graduation, Cooke began showing her jewelry and artworks and was becoming recognized as an emergent artist. Her inclusion in the landmark traveling exhibition Modern Jewelry Under Fifty Dollars (1948), organized by the Walker Art Center (Minneapolis, MN, US), placed her alongside nationally recognized and respected studio jewelers such as Harry Bertoia, Margaret De Patta, Claire Falkenstein, and Art Smith, all of whom were defining a new mode of modernist jewelry that prioritized concept, simple forms, and alternative metals. Cooke was just 24 at the time, and now on a trajectory of major recognition through magazine articles and exhibitions. After Modern Jewelry Under Fifty Dollars, she was selected for the 1951 and 1953 Young Americans competitive exhibitions, which were organized by the American Craftsmen’s Educational Council (an arm of the American Craftsmen’s Cooperative Council, now the American Craft Council), and in 1953 alone was included in such historically important exhibitions as American Craftsmen 1953, which was circulated by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service; Fiber-Clay-Metal 1953, organized by the Saint Paul Art Gallery and School of Art; and Designer-Craftsmen U.S.A. 1953, initiated by the American Craftsmen’s Educational Council and shown at the Brooklyn Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, and San Francisco Museum of Art. In 1954, Cooke was shown at the Museum of Modern Art as part of Good Design 1954, a program that presented the most innovative and cutting-edge industrial, product, and graphic designs produced around the world, and that exists to this day.

Alongside her personal art practice, Cooke nurtured good design—a term she defined as well-made objects that had a sincerity and clarity—through her showrooms and retail outlets. In 1947, the artist purchased a dilapidated townhouse at 903 Tyson Street in Baltimore. It was in a two-block historic neighborhood full of similar fixer-uppers that attracted artistic types who added to its reputation as a miniature Greenwich Village. Cooke renovated the tiny building herself, establishing a studio in the back, a showroom in the front, and a residence upstairs. In addition to her own work, she showed that of potters and other makers she knew.

In 1955, she married fellow artist William O. Steinmetz. The couple purchased the adjacent building and expanded their business to include corporate, ecclesiastical, and private design commissions. In 1965 Cooke and Steinmetz expanded their business yet again, moving their retail enterprise—now dubbed The Store Ltd.—into a new affluent Baltimore suburban shopping development, where they displayed Cooke’s jewelry along with other examples of modern design, craft, folk art, and imported goods. Although it continues to be in business, the shop is winding down operations in the wake of Cooke’s death and will soon close.

During the 1960s, as her work grew in demand, Cooke continued taking on commissions (which she had begun in the 1950s), relishing the opportunity to create heirloom items that incorporated personal stories, symbolism, and family gems. This close relationship with her patrons resulted in an intergenerational devotion to her work, with grandmothers, mothers, and daughters all owning pieces by Cooke.

In the 1970s, she was featured in Vogue and on runways in New York and Milan, alongside the clothes of Jeffrey Beene and other designers. During this period, she also expanded her materials repertoire and went against the modernist grain by making her designs available in precious metals and stones. Yet she also incorporated found objects such as riverstones and wood, and innovative materials such as Plexiglas and lightweight slender silver tubes that could be strung in innumerable forms and wrapped in different configurations by the individual wearer. This often surprising combination of elements illustrates the intuitive approach to design that gives Cooke’s work a sense of spontaneity.

Cooke’s work throughout the 1980s to 2000s remained faithful to the modernist aesthetic she helped pioneer, maintaining her commitment to simplicity of form, dynamic movement, and good design. In the 1990s and 2000s Cooke’s artistic output continued and was documented through acquisitions into museum collections, including the Baltimore Museum of Art; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (NY); Cranbrook Art Museum (IL); Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Museum of Arts and Design (NY); Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Rhode Island School of Design Museum; and the University of Arizona Museum of Art.

She continued to be included in exhibitions throughout the country, both individual shows and group projects that charted the history of studio jewelry and modern design. These included Design-Jewelry-Betty Cooke (1995), at the Maryland Institute College of Art; Messengers of Modernism: American Studio Jewelry 1940–1960 (1996), organized by the Montreal Museum of Decorative Arts and circulated to eight other venues in North America and Europe; Women Designers in the USA, 1900–2000: Diversity and Difference (2002), Bard Graduate Center, New York; Jewelry by Artists in the Studio, 1940–2000 (2010), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Crafting Modernism: Midcentury American Art and Design (2011), at both the Museum of Arts and Design, New York and the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester; and Free Form: 20th-Century Studio Craft (2019), Baltimore Museum of Art.

Finally, in 2021, just a few years before her death, she received a career-spanning retrospective at the Walters Art Museum, Betty Cooke: The Circle and the Line. This exhibition, as well as the awards and honors she received throughout the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s—such as the Maryland Institute College of Art’s Alumni Award (1987), induction into the American Craft Council College of Fellows (1996), inclusion in the Oral History Project of the Smithsonian Archives of American Art (2004), and an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters by the Maryland Institute College of Art (2014)—have solidified her legacy in the pantheon of modern design and studio jewelry.

Cooke’s consistent devotion to simplicity and purity of form has given her work a wide appeal. Her work remains rooted in the greater ecosystem, both in relation to her immediate environment in Baltimore and the field of modernist jewelry in the United States. She participated in the art and theory of her time, yet remained uncompromising in faithfulness to her vision. Between her revolutionary designs and unorthodox material alliances, and her support of other designers and artists through her shops, Cooke established herself as a cornerstone of a generation. Her wide-ranging influence and blend of good design and hand craftsmanship came to define an era.

Related: AJF published a review of Betty Cooke: The Circle and the Line, by Kimber Wiegand, here.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and we will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org