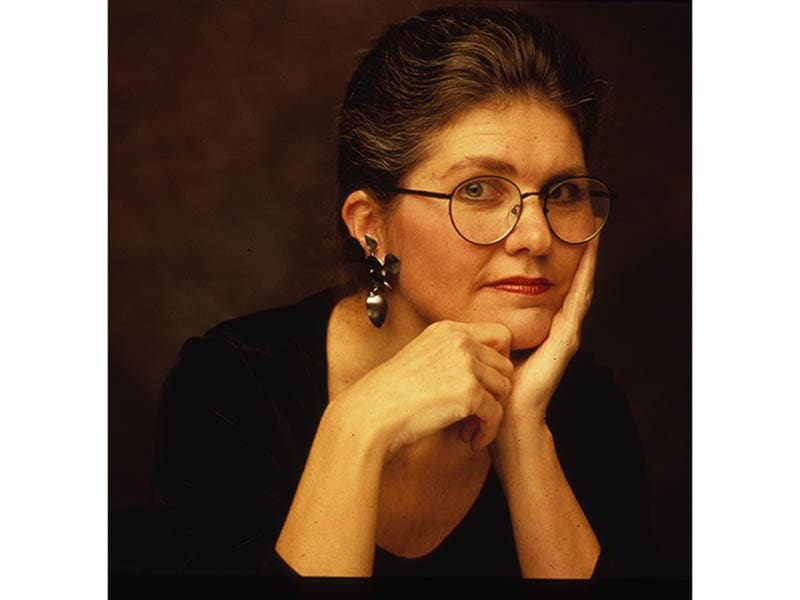

- The Society of North American Goldsmiths honored Sharon Church (1948–2022) with its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018

- An American Craft Council Fellow, she taught in the Craft + Material Studies department of the School of Art, The University of the Arts, in Philadelphia, PA

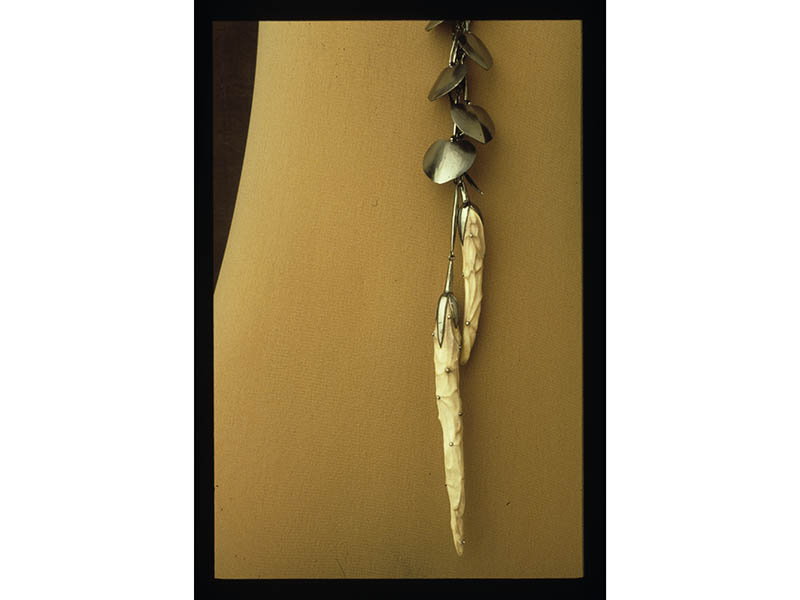

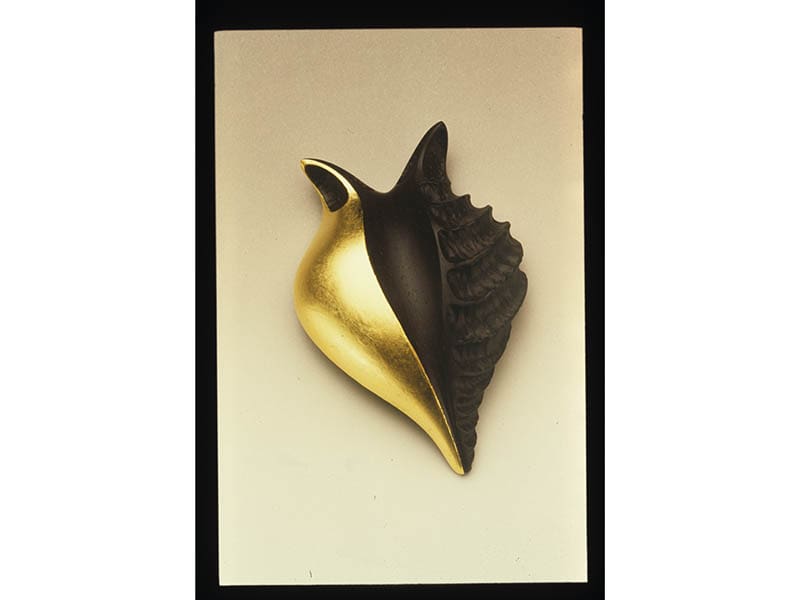

- Her jewelry often contained carved bone and wood in forms inspired by nature

Seventeen years ago, Sharon Church handed me a curious gift that appeared to be nothing more than an old wad of dirty tinfoil. Roughly the size and shape of a stout fingerling potato, it was tucked in a small lipstick-red organza pouch, which seemed a bit fancy for such an unassuming wad of foil. It was an owl pellet, she explained, and who knew what treasures would be revealed when I began to dig through it. She told me to reconstitute it in water and warned me it might not smell so good.

I never did disturb that owl pellet in its shiny foil wrapping. Instead, I kept it close, taking it with me through four moves, always aware of exactly where it lived on the shelf by my bench in each studio. Perhaps it was because I preferred the space of not knowing that I left this gift untouched for so long, sticking with the magical possibility of that owl’s regurgitation rather than risking the disappointment of its reality. Its garishly overdressed presence served as a constant reminder of the particular wisdom to be found in Sharon’s philosophies of teaching, living, and making. I realize, of course, that this is a heavy burden for an owl pellet to carry. But it was this humble token, and the devilish twinkle in her eye as she had handed me the dark, beautiful mysteries of life and death cloaked in owl puke, that I remembered on December 26, 2022, when I heard that she had died.

I think of Sharon Church as my fairy godmother. She offered me my first college teaching position in 2001, before I had any idea I even wanted to be a teacher. I taught beside her at UArts for seven years. All the while she patiently burnished my rough edges, deepening my commitment to jewelry as art, and profoundly influencing the teacher I would become. Our ongoing conversations about jewelry, beauty, and life have sustained me during times of questioning. To me, Sharon was the mother of all things.

She was tall, with piercing blue eyes, and carried herself with an unfussy elegance, from the elaborate, oxidized silver pod and leaf earrings that forever adorned her lobes right down to her long, graceful feet, always shod in handsome tapestry slippers. I was in awe of her ability to flawlessly apply her lipstick without a mirror. It’s funny, the things one remembers.

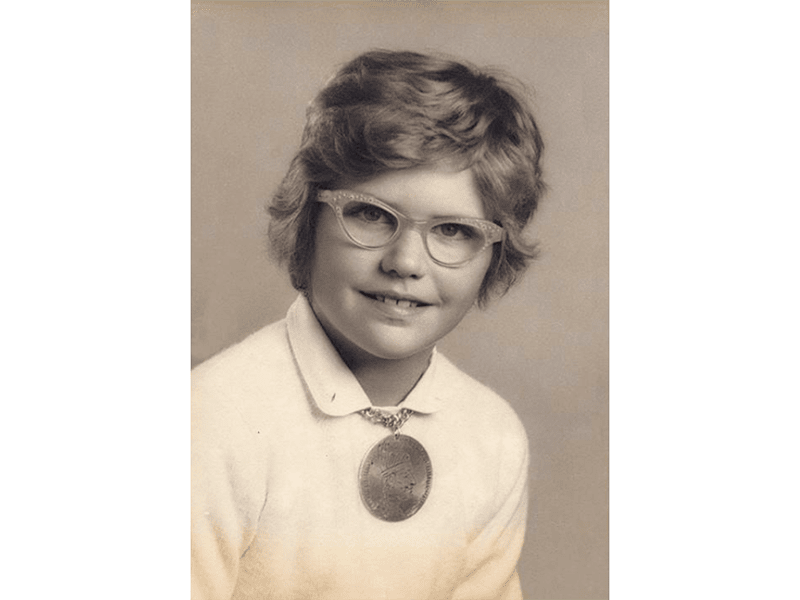

She grew up in a creative household and credited her stylish mother as inspiration. Her mother made things, wore fabulous costume jewelry, enjoyed being fashionable, and understood the power of adornment. Sharon loved watching her mother get dressed up. Even as a child, she was a decorative artist, embellishing Easter eggs, modeling with home-made clay, even enduring the pain of hot candle wax to make molds of her fingers. Sharon made her first piece of jewelry when she was 11 years old. Working from a necklace kit, she engraved the aluminum medallion, suspended it from a chain, and wore it proudly.

In high school, Sharon had a demanding music teacher who made the students sing the same song over and over and over again until they got it right. Sharon found this practice arduously thrilling, discovering the joy and satisfaction that could be attained through the rigor of discipline and craft. This practice became a part of who she was. It defined her expectations of her own work and, later on, that of her students. She never considered a piece of her work finished until no aspect of it bothered her.

Sharon would go on to discover jewelry while studying art at Skidmore College in the late 1960s, when she wandered into Earl Pardon’s jewelry class. She became enthralled by the women who were in the studio working with fire and molten metal. Suddenly, she found herself overcome with an urgent desire to explore the elemental Promethean power found in the creative force of wielding fire and manipulating metal.

After graduation came a short, unbearable stint as a legal secretary, and then graduate school at RIT studying with Albert Paley and Hans Christensen. Afterward, Sharon began teaching, first at Skidmore. In 1979, she moved on to the Philadelphia College of Art—now the University of the Arts—where she taught for 35 years and would be recognized with numerous prestigious awards.

Sharon was a brilliant, generous, and demanding educator. She was a fierce advocate and a skillful critic, but she also appreciated the humor of it all. She could be tough as nails, but I remember her exquisite hands as she deftly demonstrated a technique in tremendous detail. Her hands embodied the reverence she held for making, for materials, for the sharing of knowledge. I remember the way her hands would hold a student’s piece as if cradling an irreplaceable truth, knowing that the intimacy of making, touching something, or wearing it, was its own language, another way to understand. That communing over these things was its own sort of magic, and an undeniable reason to be. Any of her students will tell you. There are generations of them, and they can be found everywhere. They are our professors, our editors, our curators, they are our practicing artists and jewelers, and they shape our field in a myriad of ways. Sharon has indelibly marked our world, and the quiet strength of this influence reverberates endlessly.

For Sharon, teaching, learning, and making art were inextricably bound together. One nurtured the other in an endless cycle. She loved being a student and took classes to continue learning new techniques in various mediums. She understood the reciprocal nature of teaching, that a good teacher will learn as much from teaching their students as their students will learn from being taught. That asking the right questions simultaneously drives an artistic practice and reveals us to ourselves. In this active space of exchange, the possibility of transformation exists for everyone.

I was first introduced to Sharon’s work when I was a student at New Paltz in the mid-1990s, where she was invited as a visiting artist. She was just a few years past two momentous life experiences that had each profoundly affected the evolution of her art. The first was the birth of her daughter, and the second, the untimely death of her first husband.

I remember the eloquence and conviction of how she spoke about her work, and the strength of her desire to simultaneously hold these two elemental truths, surrendering to the grace of both the darkness and the depth of beauty contained there. For Sharon, nature provided an expansive window through which she could probe the endlessly regenerative and gorgeous cycles of life, death, and rebirth, and through this, come to understand her own. She understood that to experience death was to peer into the deepest truths found in the paradoxes of love, both the profound pleasures and the inevitability of loss inherent to being alive.

A thousand hammer marks gently kiss the surfaces of her foliage, belying the skill and force required to transform thick silver sheet into such delicately tapered leaves. Tumbling down the torso, this vine seems to plumb the body, a reminder of the gravitational pull that grounds us, while simultaneously embodying an ethereal weightlessness. The vine flows from a ripe bud on the verge of bloom suspended from the center of the sternum, each leaf marking the passage of time, terminating with two desiccated pods, poised as if ready to disseminate their seed. The flower and the fruit are delicately carved in antler. Old mine-cut diamonds are strategically placed, one centered in the bud as if to signal and seduce pollinators, the others scattered like dew drops upon the wizened pods, their sparks of light whispering secret possibilities of that elemental life force yet contained within.

Sharon’s artistic process was an intuitive one, her hands in persistent, deep conversation with her subject matter, her imagination, and her materials. She constantly considered where her work fit within the context of all the jewelry that had ever come before hers. She was a material sorceress, and the transmutation of her materials was of primary importance to her, as were the curious and seductive qualities of beauty. Her ability to carve into a piece of ebony or antler, as if to release its soul, created objects that seemed to contain the purest essence of a breath.

Her jewelry revealed something about the transformational experience of living things that one might otherwise miss in merely being alive in this world. The painstaking virtuosity of her craft is evident in even the most diminutive elements found in her often elaborate constructions. While she considered herself a generalist in many ways, and drawing was a dedicated part of her artistic explorations, she remained deeply convinced of the breadth of artistic possibility that jewelry possesses. Her work comes alive on the body.

In the midst of the doldrums of the first week of this new year, I found myself sitting at a table in my studio with a cup of warm water, a pair of fine-tipped tweezers in my hand, magnifiers on my face. Gingerly unwrapping the tinfoil casing of the owl pellet, I went in search of Sharon Church.

Once saturated, it smelled vaguely of leaves and dead things in the final stages of transformation, like a dank forest floor. I was not exactly surprised by what I found. In the act of digesting, the owl had economically taken only what she needed in order to transform death back into life. Her gizzard had the wisdom to let go of what she knew she could not keep. What was left was the material evidence of the tenuous beauty of this process—a dense hairball with a scattering of seeds and the delicate confetti of skeletal remains from a trinity of field mice. There were strands of miniature vertebrae, three skulls, an assortment of ribs and femurs, and the tiniest molars for chewing, no more significant than individual grains of sand in an hourglass.

Sharon understood that we contain multitudes, that we are made of the same stuff as the stars that guide our journeys across vast oceans, that one day we too will succumb to death, decomposing back into the earth only to begin again, and she understood our folly in trying to hold on too tightly to anything at all. She found evidence of this everywhere she looked in the world, but especially in nature and art. This knowledge bears weight, yet she still got up every morning and poured herself a cup of tea, went to her bench, and made something, because that was a true gift—the ability to lose oneself in the pure wonder of making something beautiful that could lend meaning to all the rest.

Sharon Church, you are a force of nature, now, and forever.