On January 29, 2022, Berend Peter Hogen Esch passed away; he was the last surviving member of the BOE-group.

Early in his career, Berend Peter Hogen Esch chose his double first name, Berend Peter, as his artist’s name. He died in the house where he had lived since 1979 with jewelry artist Marion Herbst (1944–1995), and later with his second wife, Lindsey Bogle, and finally his third great love, Melitta Steenhuis.

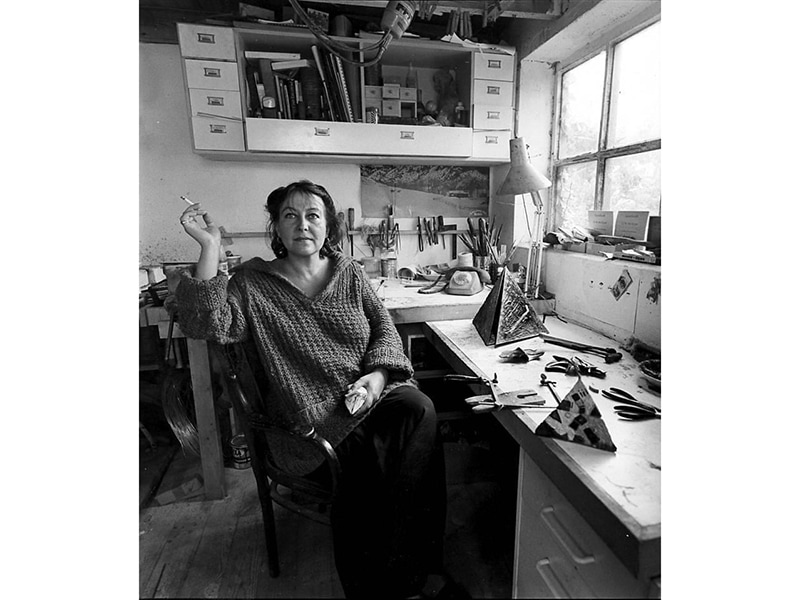

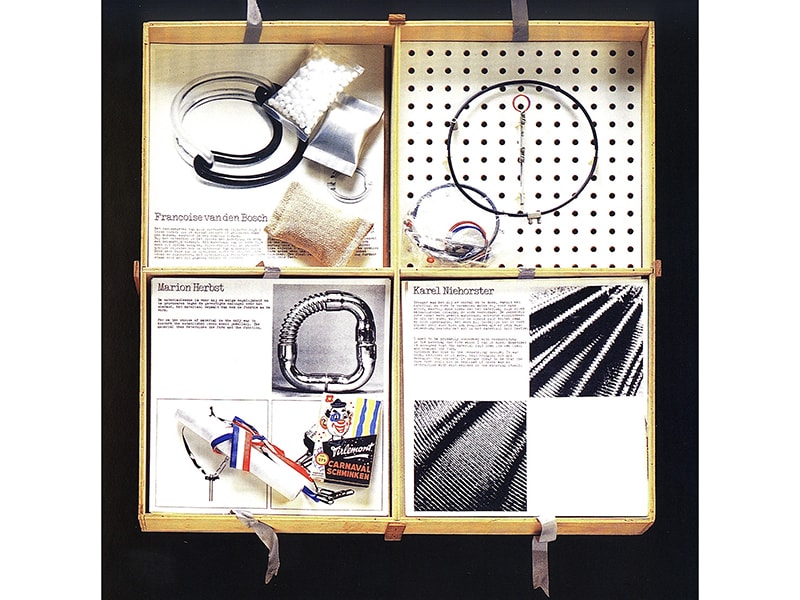

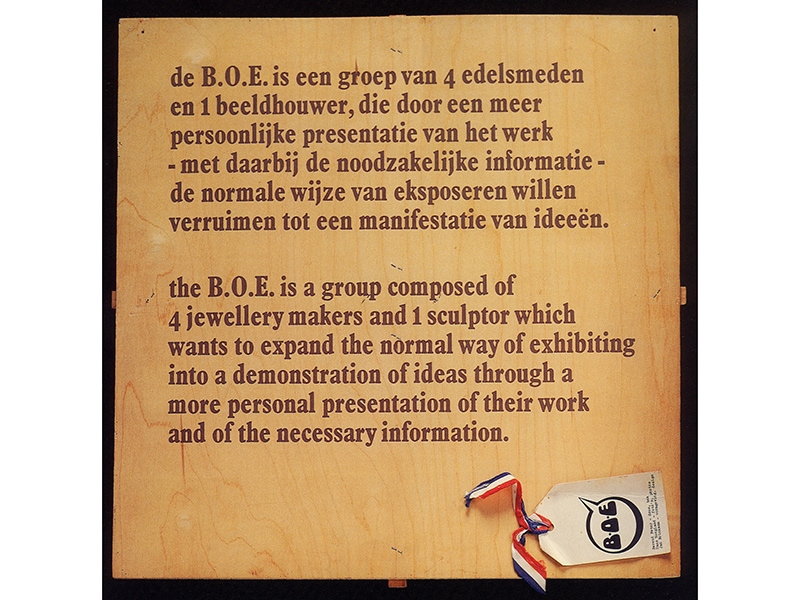

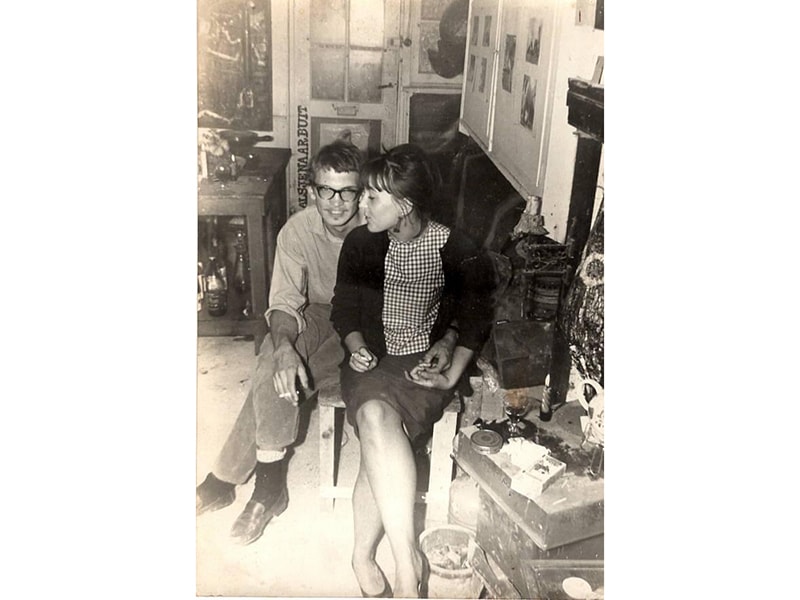

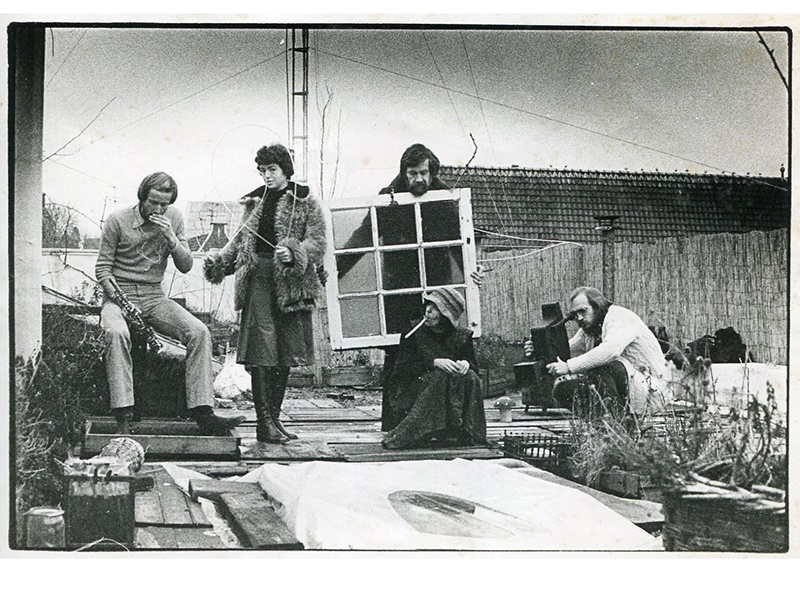

He spent his last days in an extension of the house that overlooked the gorgeous garden, accomplished himself by diligent labor, filled with a twittering variety of birds and huge bamboo waving in the breeze. In the old dike house, underneath the dike of the Maas River, there is still a lot that recalls Herbst. Here they found their refuge, escaping from the busy, dirty city. Here they both had beautiful studios—Herbst in the house (once home to two cows), Peter in the enormous barn crammed with materials, tools, and machines. Herbst and Berend Peter got to know each other at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie (then called the Institute for Arts and Crafts Education), in Amsterdam, where they both taught after finishing their education. They graduated in 1968 and 1969 respectively, Herbst from the Jewelry Department, Berend Peter from the Sculpture Department. In 1973, one sculptor and four jewelry makers—Berend Peter, Herbst, Françoise van den Bosch (1944–1977), Onno Boekhoudt (1944–2002), and Karel Niehorster (1932–2003)—established the BOE-group. BOE was an abbreviation for Bond van Oproerige Edelsmeden; in English, the Union of Rebellious Goldsmiths.

The BOE-group wanted to develop a better understanding of contemporary jewelry and strived to unite the growing group of young goldsmiths into an interest group. They were also driven by a resentment against the uniformity that had taken hold of Dutch jewelry in a short time. The policy of the Dutch government, expressed in exhibitions organized by the NKS (the Dutch Arts Foundation) and the BBKS (the organization for traveling exhibitions of Dutch art and design abroad), was in favor of minimalist, modernist, and serial jewelry. The BOE-group wanted to disrupt this uniformity by arguing for a more personal presentation, where in their view everything should be possible. (The Dutch word boe means “boo” in English, both in the sense of scaring someone but also in expressing disapproval. In the case of these artists, it expressed contempt for the conformity of the jewelry being promoted at the time—a happy coincidence.)

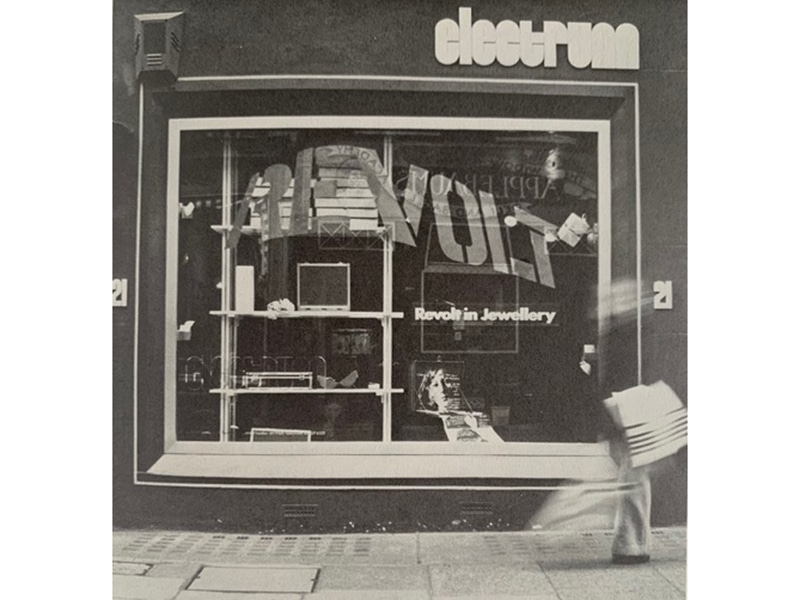

Inspired by this new élan, in 1974 Ralph Turner invited the group for an exhibition at Electrum Gallery, in London, where Turner was co-director and manager from 1971–1974. It all came together very fast and, as Berend Peter told me, the title of the exhibition, Revolt in Jewellery, was already applied to the window when the five artists arrived at the gallery.

The set-up of the exhibition was designed collaboratively by the group members. But Berend Peter must have played an important role in this, because of his spatial awareness and capacity to build everything he wanted or anyone needed. Filmmaker Agna Arens, who made a film for Dutch broadcasting about the BOE-group in 1974, characterized him as “the big tinkerer among us, who made objects with a smile and a wink at jewelry.”[1] The famous BOE-Box (included in many international museum collections) was Berend Peter’s, design and execution.

A novel feature of the BOE exhibition in London was the presentation of the jewelry in suitcases and on life-size silhouettes of the five artists. This was exactly the personal touch they strived for. The combination of the five artists also showed a personal point of view. The artists made diverse work, from minimalist and serial (Van den Bosch), via lyrical and artisanal (Boekhoudt), surreal (Niehorster), and playful, colorful, and humorous (Herbst) to Berend Peter’s playful objects.

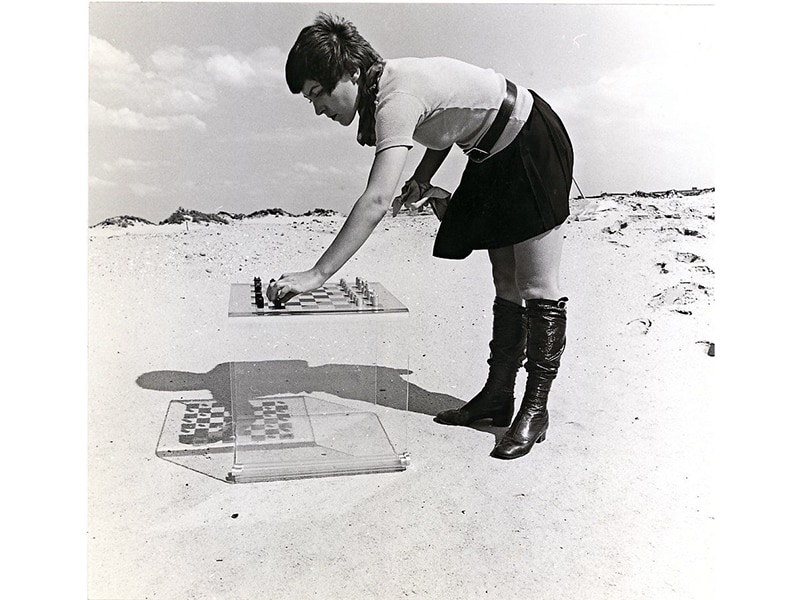

The suitcases were a reference to traveling, because in those days a trip to London was quite an undertaking, by ferry and then train. All the suitcases were different, and individually adapted to the work of the artist. Most of the suitcases were made of Perspex, or acrylic glass as it was then called. Many artists and designers experimented at the time with this rather new industrial material. Berend Peter made several suitcases in this period. For the Revolt in Jewellery exhibition, he took two suitcases, one of which showed a collection of “unwearable rings.” Both suitcases have gotten lost, unfortunately. The “unwearable rings” are temporarily in my collection.

Thanks to the use of suitcases and the silhouettes, the BOE-group playfully broke the hegemony of “Dutch smooth” that had in a few years’ time become the trademark of contemporary Dutch jewelry. The BOE-group only existed for about one year. It resulted in the establishment of the VES, the first Union of Goldsmiths and Jewellery Designers in the Netherlands, in 1975, achieving one of the group’s objectives.

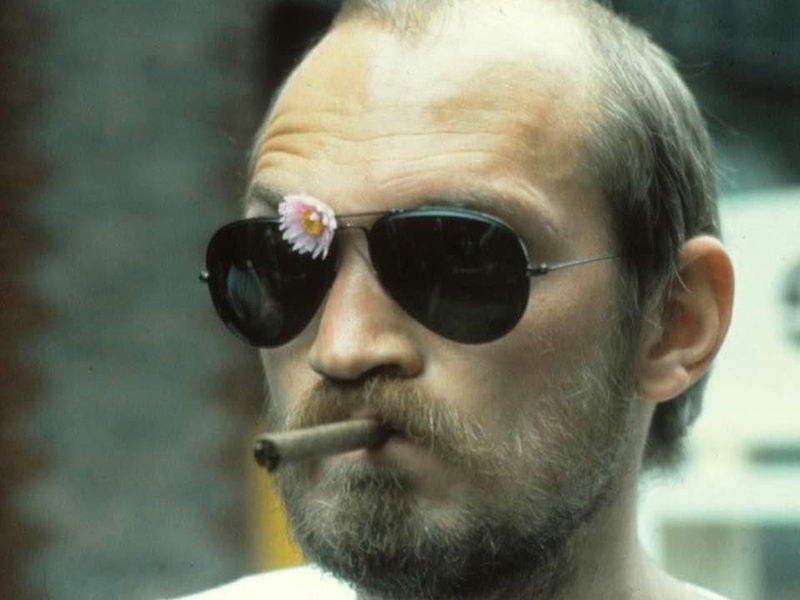

Berend Peter was the youngest of the group. He survived them all for many years, and sort of developed into the group’s chronicler and treasurer. He was the right man for this. He knew how to appreciate history. For years, he shared interesting, well-written stories about his own work as a sculptor, and about Herbst. He did this initially on his blog, and then on his Facebook page. In this way, he kept the memory of Herbst alive with photos and cheerfully told anecdotes about their life in Amsterdam, the artistic circles they ran in, and works they made.

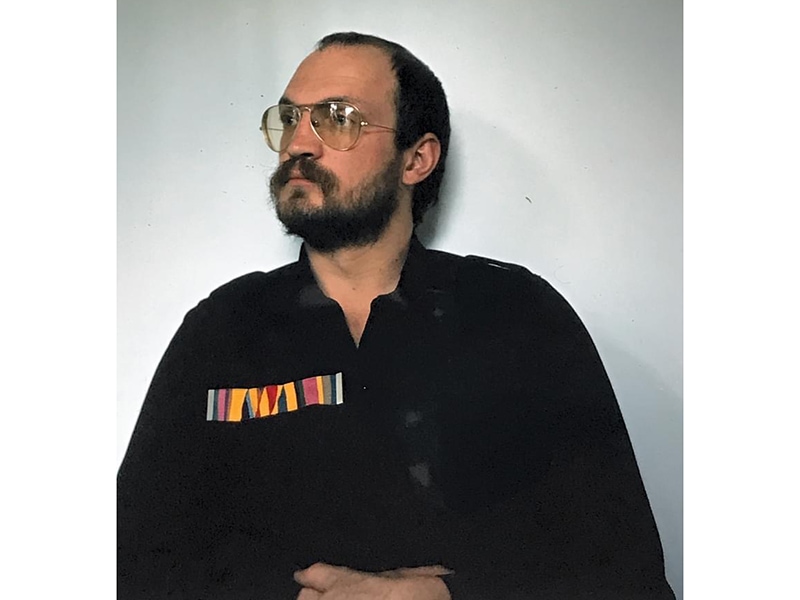

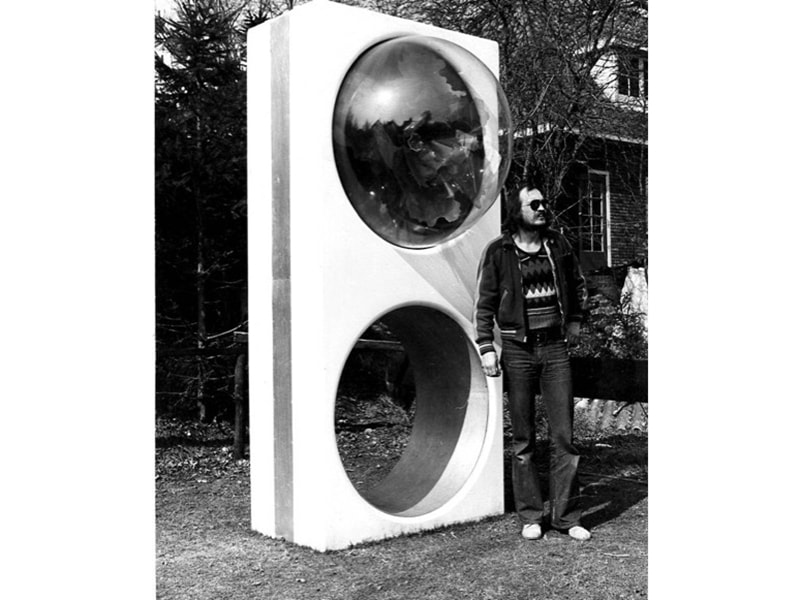

They shared 30 years of joys and sorrows and worked together a lot in the early years. In 1972, Berend Peter made a rectangular sculpture based on one of Herbst’s rings. (It has now been lost.) It had two circular holes. The upper was covered with acrylic spheres under which a rosette of rose leaves was applied. In those days Herbst made a series of such rings with miniature nature scenes. Together Berend Peter and Herbst made a film about this project, named The Big Ring, with the aim of showing that jewelry can also function as an object. Berend Peter helped Herbst build a Perspex chess table and aluminum chess pieces (1971). He was a modest man, and he didn’t think it was important to link his name to her work, but connoisseurs of the work of both can easily point out where Berend Peter’s expertise and creativity offered a solution. Sometimes Herbst used him as a model.

From Berend Peter’s Facebook posts I learned that during the start-up phase of Galerie Ra, Herbst and Paul Derrez saw each other regularly for brainstorming about jewelry and the future of the gallery. Berend Peter attended these meetings now and then.

When the closure of Galerie Ra in December 2019 was announced, Berend Peter posted a nice memory: “Flower manifestation Galerie RA 1977 … For this ‘flower manifestation’ Marion and I set out early to pick pockets full of grasses and flowers in the still-green areas of land around Amsterdam. A kind of ‘overcoat’ of wire netting was made by us, in which flowers and grasses were put. In this photo Paul is wearing the coat. … A smiling Marion is in the photo, wearing a white dress.” He forgot to mention himself, half hidden behind Herbst’s flower crown.

Berend Peter was a kind and generous man, modest and interested in anyone who crossed his path, and an energetic maker and doer. He was the kind of person who generously shared things (jewelry, materials, objects, furniture he built himself) from his rich past with artists and others whom he deemed the right recipients. As a sculptor he realized many sculptures in public spaces, and he was the secretary of the Dutch Society of Sculptors for some time.

The last year, in his Facebook posts, he shared one after the other stories about his life and his sculptures, where and how they were made, and what had happened with them. In September 2021, he was happy and surprised to watch an item on Dutch broadcasting about the new CCNL, a depot for the national collections of four museums in The Netherlands. During the program, the director of this storage institute gave attention to a sculpture by Berend Peter. The artist had no idea that his One Person Air Effect Vehicle (1979 or 1980) had ended up in “the physical memory of the Netherlands,” as CCNL is nicknamed.

Besides this, he wrote passionately about his garden, trees, insects, birds, and flowers, about carpentry, sawing, and composting, and about how happy he had been with his three great loves. Melitta Steenhuis, his widow, lovingly cared for Berend Peter in his beloved home until his end. His candidly honest accounts of his death sentence (of pancreatic cancer, diagnosed in April 2021) and the degeneration of his body were admirable—moving and inspiring to read. Not long ago, his followers even saw him “lying for a trial run” in the coffin he built himself from recycled pallet wood. Rest in peace, dear Berend Peter.

[1] Marion Herbst, 1969–1982 Een overzicht, Amsterdam, 1982, not paginated.